These Fish Posed for Pencils, Not Cameras

Artist Joseph Tomelleri’s scientific drawings of Salish Sea fishes can be easily mistaken for photographs.

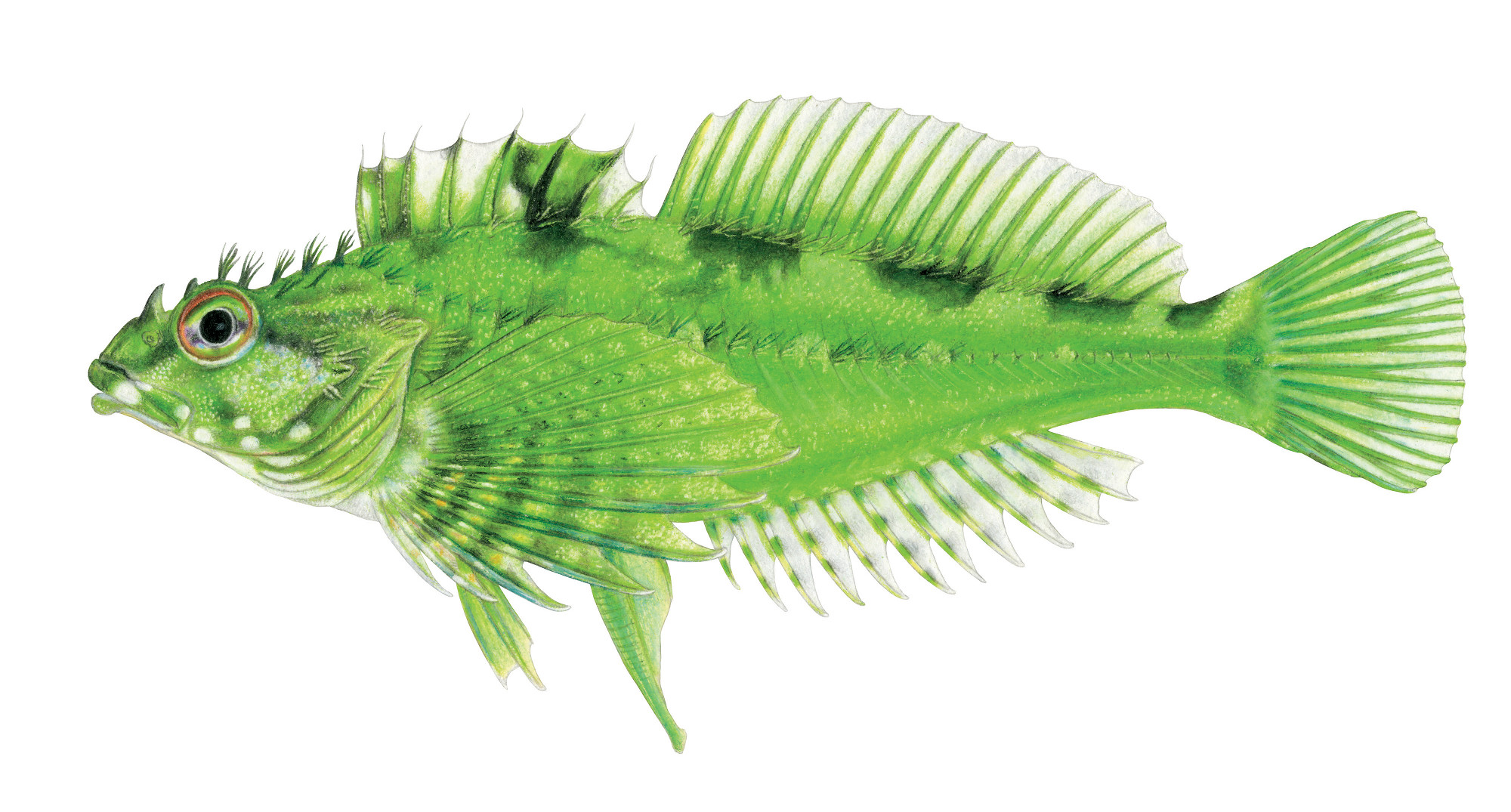

Kelp greenlings ("Hexagrammos decagrammus") are found in the rocky reefs and kelp beds between the Aleutian Islands near Alaska and the coast of La Jolla, California. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

The golden spots on the female kelp greenling above are more true to the markings on this Salish Sea fish than the off-color yellow specks you’ll see in most photographs. That’s because the image above isn’t a photo. It’s actually a hand-drawn illustration by biologist and illustrator Joseph Tomelleri.

Tomelleri draws fish for scientific research. His models are specimens that he receives from researchers or that he collects himself. Over the past 30 years, he’s drawn more than 1,200 scientifically accurate illustrations of about 900 species, carefully rendering the edges of their scales, the exact number of fin rays, and even the faint lateral line, or sensory organ, that runs down the sides of all fish. His lifelike artwork has been featured in thousands of publications, he estimates, helping ichthyologists better understand fishes and their changing ecosystems.

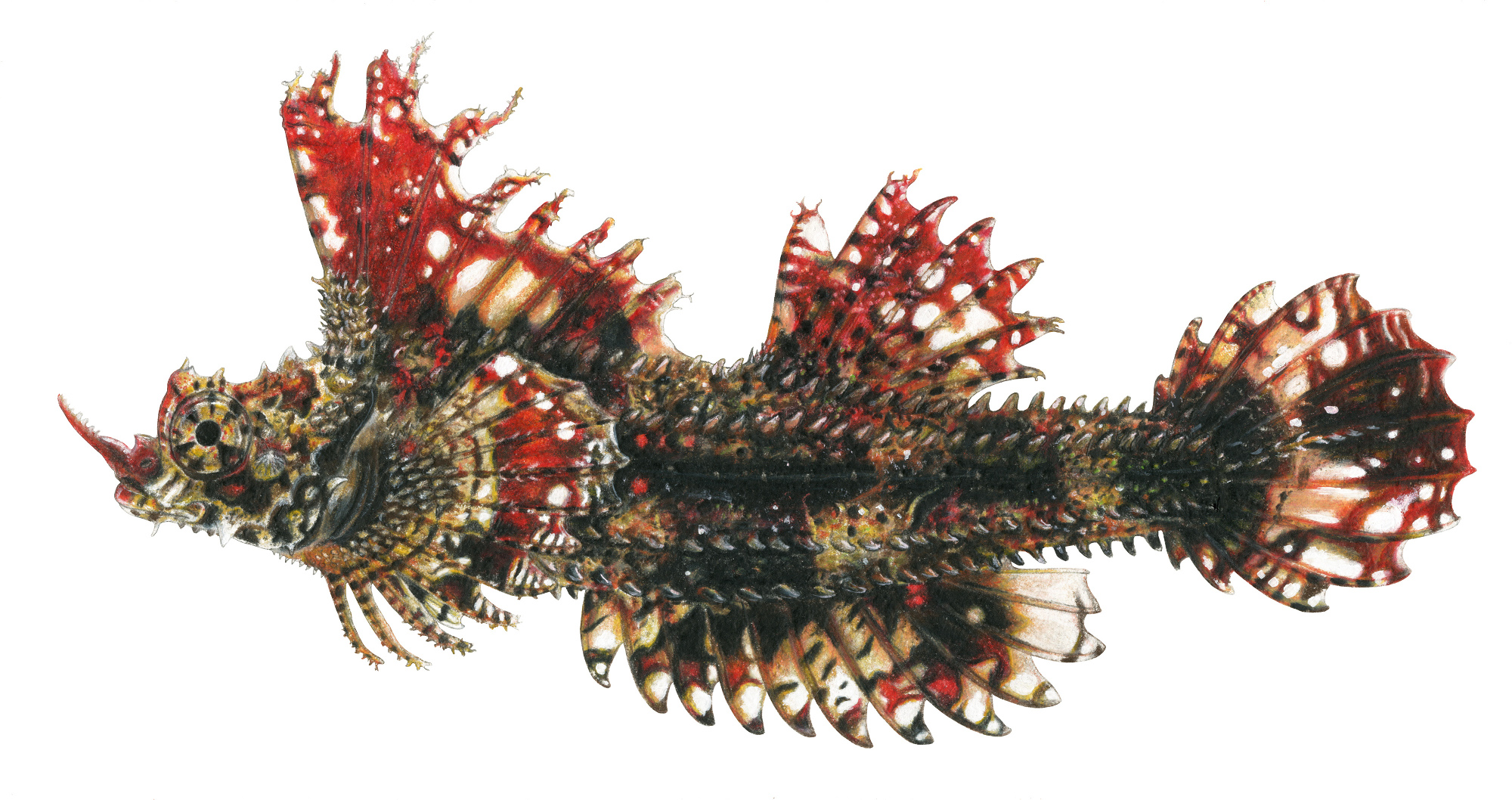

The kelp poacher ("Agonomalus mozinoi") is a mere 3.5–9 centimeters long, and was the smallest species Tomelleri illustrated for the comprehensive Salish Sea survey. To draw smaller fish, Tomelleri uses a dissecting microscope to see intricate details. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

Historically, ichthyologists turned to artists to illustrate fish anatomy and morphology in their studies. But even in the age of digital photography, there are good reasons why Tomelleri’s scientific collaborators prefer his artist’s hand to photographic documentation. As Tomelleri explains, it can be difficult to find representative photos of a single fish species where identifying features such as color patterns and fin arrangement are consistent. “You may have some pictures taken underwater, with a fishermen holding them, or with the fish laying at the bottom of a boat,” Tomelleri says. “All the details that a scientist wants to show on a specimen would be all over the place.”

Fish trawled for research purposes can also become deformed or mutilated. But an illustrator can take a damaged fish and reconstruct it in a drawing, says James Orr, an ichthyologist at the Alaska Fisheries Science Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who recently collaborated with Tomelleri.

It’s important that scientists have “a clear picture of what a fish looks like and its morphology,” says Orr.

This is a redbanded rockfish ("Sebastes babcocki"). There are 28 known species of rockfish in the Salish Sea, each with a distinctive color pattern. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

Fishing trips that Tomelleri took with his father as a child spurred his curiosity in the creatures that lurked in deep holes and crevices underwater. In 1985, following his graduate studies in range management and botany at Fort Hays State University in Kansas, Tomelleri and his former classmates created a booklet of the fish living in a creek by the university. When photos failed to represent the fish accurately, Tomelleri stepped in to draw them.

“When you see a photograph, you can tell if [the fish has] been dead for two minutes,” says Tomelleri. “They just lose that little bit of spark.”

The fluffy sculpin ("Oligocottus snyderi") is common along the outer coast of British Columbia near the Queen Charlotte Islands and Vancouver Island. It dwells in protected tide pools and rocky habitats. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

For one of his latest projects, Tomelleri worked with Orr and University of Washington ichthyologist Ted Pietsch to create scores of color pencil illustrations of fish species in the Salish Sea, which spans from Washington State to British Columbia. Orr and Pietsch have been collecting and documenting fishes in these inland marine waters since the mid-1980s and released an updated report this past September on species presence and diversity in the area. The paper, which features 23 of Tomelleri’s illustrations, is just a prelude to an upcoming 1,000-page comprehensive book that will contain locations, distribution, and habitats of all the known fishes in the Salish Sea, which now number 258.

The sockeye salmon ("Oncorhynchus nerka") is found all along the North Pacific from Japan to southern California and is an abundant fish species in the Salish Sea. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

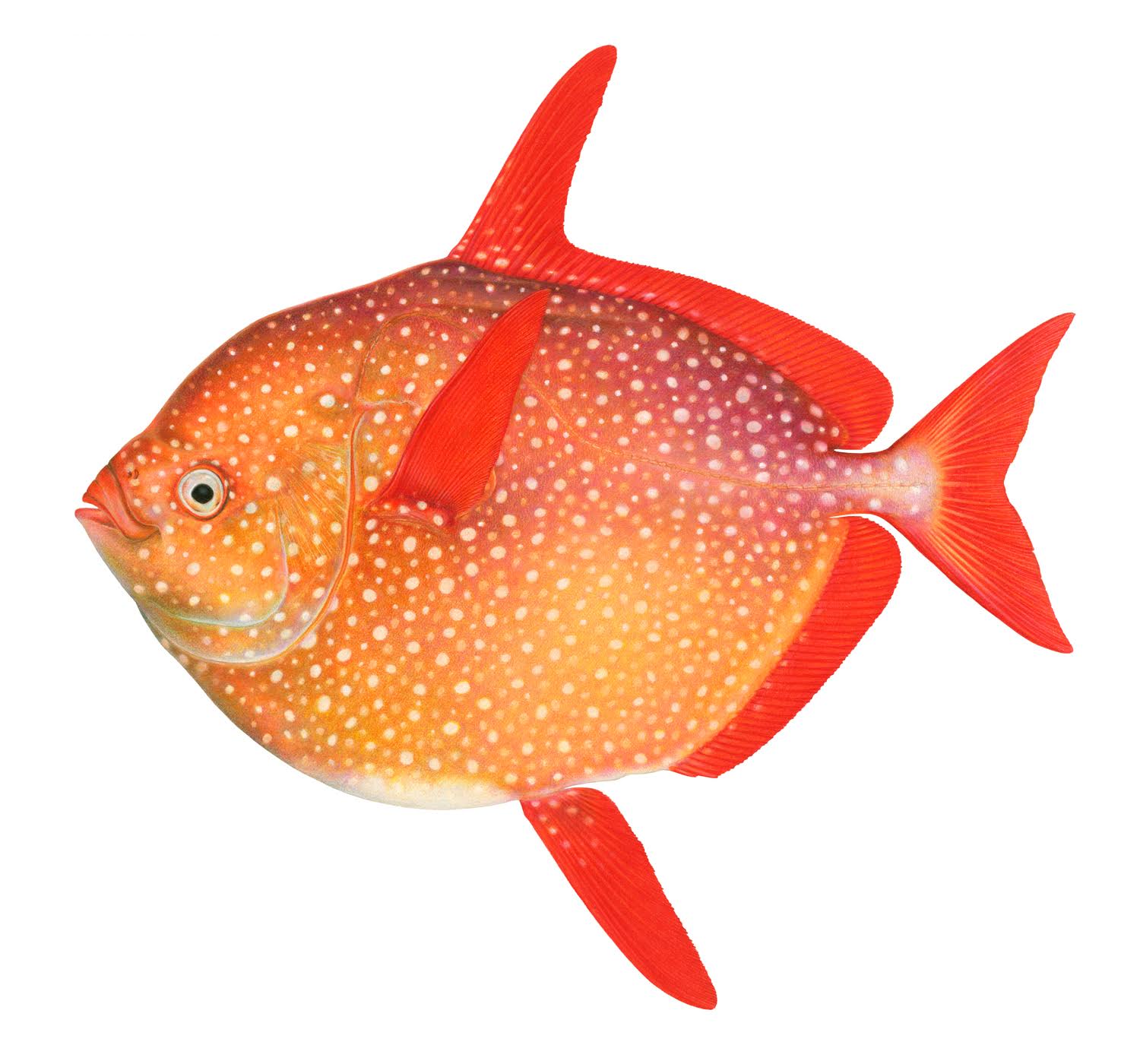

The Salish Sea is a young system, according to Orr. Glaciers covered the area until 10,000 years ago, giving way to features like Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia. Its vast range of habitats has given rise to diverse fish fauna, including the rare warm-blooded opah and the more common sockeye salmon—two species that aren’t often found in the same region.

It’s been 35 years since the last in-depth survey of Salish Sea fishes was completed (and that survey focused only on Puget Sound), and Orr has big expectations for his team’s follow-up. “It’ll be the first time I think [these fishes have] really been accurately depicted,” he says. “It’s like the fish is just jumping right off the page.”

As part of the Salish Sea survey, Tomelleri received a 40-pound opah, also known as a moonfish ("Lampris guttatus"). A blown-up, life-size version of the illustration was presented as a retirement gift to survey co-author Ted Pietsch. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

As Orr and his colleagues collected the Salish Sea specimens, they sent them to Tomelleri, whose Leawood, Kansas studio looks more like the collection room of a natural history museum. Hundreds of fish specimens mingle with the Prismacolor pencils that give Tomelleri’s illustrations their “smooth, wet look,” as he puts it. One illustration—which can range from 6–7 inches to more than 20 inches long—generally requires an average of 25 hours to complete, though it can take much longer. To create the opah above, he racked up 70 hours at his drawing desk.

Tomelleri tries to mimic the iridescence of fishes’ scales, as in this drawing of a Pacific chub mackerel ("Scomber japonicas"). “Even the fish that are silvery actually have a lot of color in them,” he says. Image courtesy of Joseph Tomelleri

With every fish he draws, Tomelleri shades in a corner of the bigger picture of fish diversity in North America. “I’ve done other landscapes and wildlife, but that doesn’t interest me as much,” he says. What he really loves is venturing out into rivers and creeks with a big net or seine in hand and capturing the fish that duck in dark places.

“If you don’t have them fresh or see them live, you don’t see those colors. They are really beautiful and subtle sometimes,” he says. “That’s what I love to try to mimic.”

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.