Forecasting Financial Crises, Thawing Water Bears, and the Pros of a Big Deductible

11:45 minutes

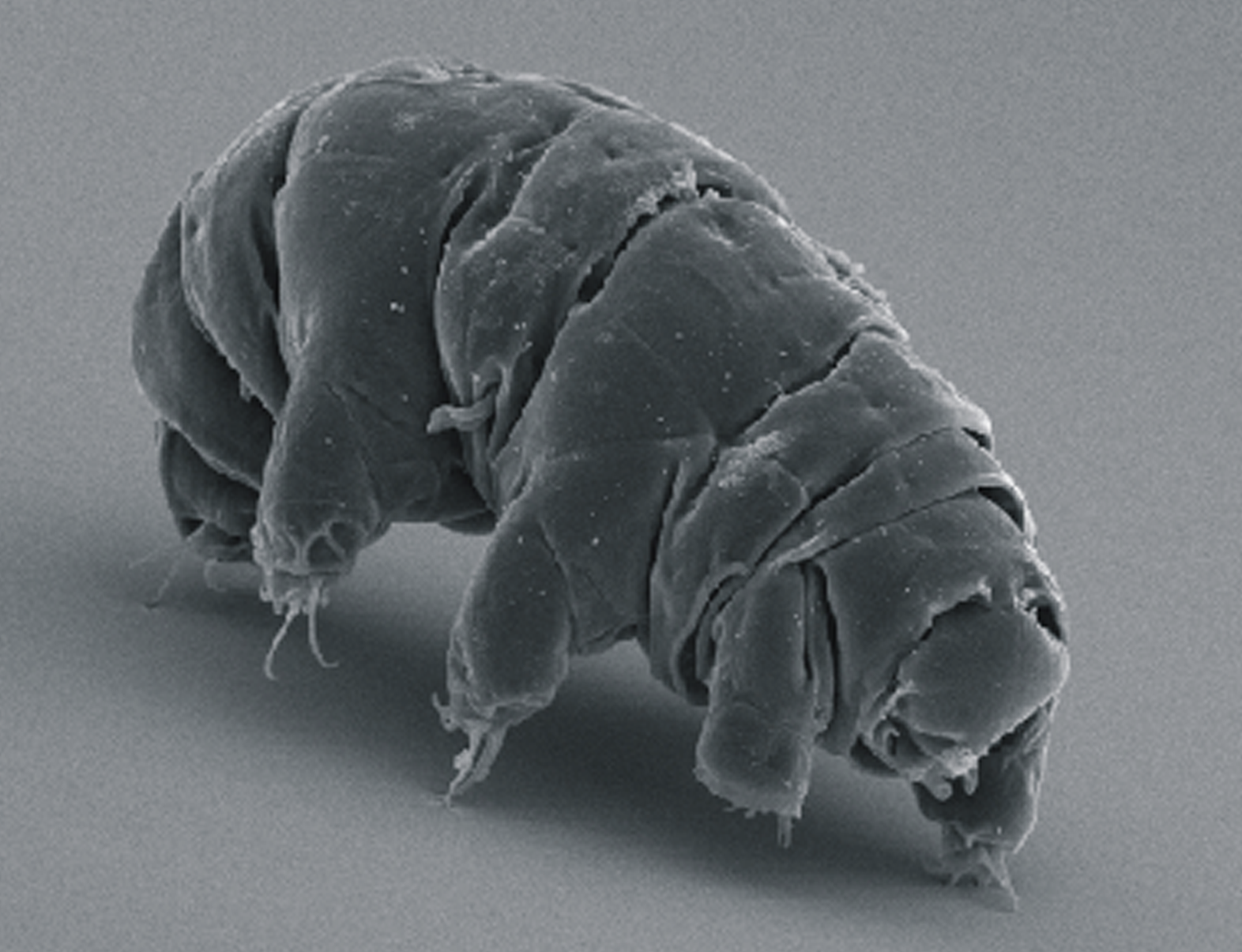

A group of economists is taking a page from nature’s book, hoping its organizing principles can guide them in building better models that forecast financial meltdowns. Plus, researchers revived tardigrades—also known as water bears—from a 30-year deep freeze. Amy Nordrum, a science writer for International Business Times, discusses these and other selected short stories in science. And Margot Sanger-Katz of The New York Times takes a look at the potential good and bad aspects of having a high deductible on your health care plan.

Amy Nordrum is an executive editor at MIT Technology Review. Previously, she was News Editor at IEEE Spectrum in New York City.

Margot Sanger-Katz is a health care correspondent for the New York Times. She’s based in Washington, DC.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A little bit later, we’re going to be talking about the worldwide impact of El Nino. You know, it’s not just a local thing.

But, first, the 2008 financial crisis. You remember that I’m sure if you had any money anywhere. It was one of the worst economic downturns since the Great Depression. And you would have thought that someone would have added up all the numbers and seen the meltdown coming. But the alarms flew past most experts in all areas, even iconic Alan Greenspan said everyone missed it from academia to the Fed.

How can we build better financial forecasting tools? Well a group of financial experts is looking to ecologists, rather than economists. Amy Nordrum is here with that story and other selected shorts and science. She’s a science writer for International Business Times here in New York. Welcome back.

AMY NORDRUM: Thank you, Ira. Good to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Good to have you. So, what’s wrong with economic models we have? I mean they call it what the dismal science, right?

AMY NORDRUM: So the traditional economic models that most of the world relies on right now basically distill all the behavior in an economy. All the things that you do, and all the things that I do down to what they call a rational actor. A single individual. You can think of it, maybe in our case, as the average American, who basically is a composite of all the different beliefs and attitudes and priorities that exist within a system.

Of course, we know that the economy doesn’t actually work that way. There’s many different people acting on different beliefs at any given time. So a couple of economists made a proposal this week in a major scientific journal, Science, saying that we should really build out better economic models that are more representative of the diversity of beliefs that we see exist in the economy. And they’re looking to, like you said, ecologists to do this. If you think of the economy, it’s a system or network made up of people, institutions, like banks and companies, and federal regulators. And all of these different players interact with each other. They form relationships.

And economists see a lot of parallels between that network and those that, for example, ecologists deal with. You can think of food webs, in this case, where one species is highly dependent on the health of another. So their idea is that if they can adapt some of the rules that we know govern these other systems, if they can think more like ecologists or epidemiologists who track disease outbreaks, informing their economic models, they might actually be able to anticipate and understand economic phenomenon better, such as the next financial crisis.

IRA FLATOW: And, you know, it reminds me of how slime molds can make decisions.

AMY NORDRUM: Right.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re be using that kind of biology.

AMY NORDRUM: So this entire idea is based on something called complexity theory, which is basically that complex systems– and that could be the ants in an ant hill or the neurons in our brain or, in this case, the individual players in an economy– abide by a set of rules or organizing principles. And if you can just understand and identify these rules and track them over time, you can get an idea of what’s going on. And, perhaps, even see what’s going to happen down the road. So they’re hoping to apply this complexity theory to economics in the same way that, for example, weather forecasters have applied it to understanding our weather system, measuring things like atmospheric pressure, humidity, and, then, forecasting oncoming storm.

IRA FLATOW: That’d be interesting to see how that works. Let’s move on to your next story, and this is a study that came out looking at plant intelligence. We don’t think of plants having brains or anything, do we?

AMY NORDRUM: They don’t get enough credit, frankly. So Peter Crisp at Australian National University published a paper just today in Science Advances talking about memory and forgetfulness in plants. And scientists have known for a while that plants do have some capacity to form memories and to forget. So, for example, this often happens in times of stress. If there’s a particularly dry period, a plant might shrivel up. And on its recovery, once it starts raining again, it may remember that period and choose not to grow quite as big, just in case there’s another dry period around the corner.

So, he was interested in the fact that plants don’t always do this. Sometimes they actually choose not to remember and grow back to their full size that they were before. He’s trying to figure out basically when they remember and when they forget. And he’s come up with this theory he says that he thinks the advantage to remembering sometimes is not so great as the advantage to just forgetting and kind of throwing caution to the wind. So if the plant spends more resources actually adapting and preparing itself for that next dry period, it might just say, forget it, I’m going to go ahead and grow back to my full size. And I’ll just take the chances that it’s going to happen to me again.

This is something that he considers an evolutionary advantage the plants have developed over time.

IRA FLATOW: Because the last thing you think of is a plant having any memory or intelligence or thoughtfulness.

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. We’re learning more about all the time. It seems that they’re able to make some sort of cost-benefit equation during that period of recovery, which is really interesting.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about your freezer. I mean my freezer, your freezer. I know a lot of us keep TV dinners or popsicles in the freezer. And you have to clean out the freezer every now and then. And this story involves a group of scientists who what were they cleaning up the freezer like we do at home?

AMY NORDRUM: It does sound like that. So this is a group from Japan’s National Institute of Polar Research. And they had a moss sample from Antarctica that had been in their freezer for 30 years.

IRA FLATOW: You mean like somebody forgot it. It was sitting in the freezer.

AMY NORDRUM: So it was still there. It had been collected in from Antarctica. And they pulled it out.

IRA FLATOW: Maybe when I was there, we took it out. I don’t remember.

AMY NORDRUM: They pulled it out, and they thawed it. And they found two tardigrades, which are these bizarre organisms. They look a little bit like swollen caterpillars inside the moss sample. And they were really interested to see if these tardigrades, which had been frozen for 30 years, were actually still alive and capable of reproducing. So, once they thawed out the sample, the tardigrades, which had been completely frozen, did start to move after a period. And, eventually, one of them actually did go on to reproduce and lay the 14 eggs that successfully hatched.

IRA FLATOW: The tards– What are these bears? What do they call them?

AMY NORDRUM: They’re also nicknamed moss piglets or water bears.

IRA FLATOW: Water bears. Right. We’ve done videos on tardigrades or the water bears. So let me understand this, they were frozen for 30 years, they defrosted them, and they came back to life?

AMY NORDRUM: That’s right. So, this is an example of what we call cryptobiosis. So, the tardigrades are actually capable of surviving extreme circumstances. And they can basically dehydrate themselves and preserve their bodies. This protects them against some of the damage that happens to our cells if water freezes inside of us. So, the tardigrades are capable of this, but they do not get the award for the longest period being frozen and able to come back to life. Roundworms actually hold that title at 39 years.

IRA FLATOW: 39 years?

AMY NORDRUM: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I’m picturing the lab. I’m picturing you pulling this out. And you want to defrost it. Now, when you have a frozen dinner, you put it in the microwave. Did they do it that way? How do you defrost the tardigrades?

AMY NORDRUM: It took a full day to actually defrost the moss sample. And, then, since the tardigrades were physically dehydrated. That’s part of their strategy. They also had to sprinkle a little bit of water on them on day two, so that they could absorb that water and come fully back to life.

IRA FLATOW: Well glad to have you back for these stories. Fascinating.

AMY NORDRUM: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Amy Nordrum is a science writer for the International Business Times here in New York.

Now, it’s time to play good thing, bad thing.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

IRA FLATOW: Because every story has a flip side. And if you’re like many of us, your insurance plan. You know what that long piece of paper is. Probably has a deductible. That’s the amount you personally have to pay before the insurance coverage kicks in. I know you know what I’m talking about. There’s a good chance those deductibles are increasing, leaving you to pay more out of your pocket. Sounds like a really bad, bad thing right? Well is there a good side to it? Here to talk us through the good and the bad of high-deductible plans is Margot Sanger-Katz. She’s a health care correspondent for the New York Times. And her article on this topic recently ran in the papers Upshot Column. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: Thanks so much for having me on.

IRA FLATOW: What could possibly be good about having to pay a big deductible?

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: Well, it’s never very fun. But the theory behind deductibles is that if all of your medical care is free, then there’s no incentive for you to be prudent with how you spend your dollars. And, so, if everyone thinks everything is free, they might go to the most expensive hospital to get their treatment. They might get treatments that they don’t really need or want, just because why not. And the theory is that when people behave this way in aggregate, it drives up health spending and it makes our premiums more expensive for every one.

IRA FLATOW: So if you have to pay a deductible, the idea is you’ll shop around for the cheapest thing. I don’t know how you shop around when you have an insurance company, but that’s what the idea is.

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: Yeah, that’s the theory. That first of all, and there’s actually pretty good evidence about this first thing, that people will just use less health care. That if you’re feeling a little crummy, and it’s going to cost you some money to go to the doctor, you might wait and see if you feel better. And some of those people are going to feel better, and then there will be less doctors visits, whereas if it’s totally free, you might just go to the doctor the second that you start feeling second. And, so, there is evidence that when you ask people to pay for their health care with their own dollars, they use less health care.

The question about shopping, I think there’s sort of more hope than there is evidence so far. That people will really work for better prices or for good deals. Because as you said, it can be pretty hard actually to find this information. Although, more and more insurance companies employers are trying to give people that can make it a little easier to comparison shop.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you know that idea that how hard it is to do this. I’m thinking a lot of people just give up. Right? They don’t go to the doctor anymore. Because it–

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: And there’s evidence about this also. What they find, and this is one of the problems with deductibles, is people do cut back. They don’t necessarily cutback in a rational way. They sort of cut back on care that they don’t need, and they also cut back on care that everyone agrees is actually really valuable, almost at the same rate.

IRA FLATOW: So, how do you think this can play out better for consumers?

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: I think it’s complicated. There definitely are some real down sides. But the real advocates for deductibles and for this idea of having people be more consumer-like in their use of health care is that we just have to really improve the transparency about the quality of health care, the value of it, and then also the price. And, so, if you hurt your knee and, you have to get an MRI. And it’s really easy to look around and see here are the five best place in my neighborhood and here are the prices. Maybe then you actually would start to see people navigating towards the cheaper places. And, then, you might see some price pressure where the expensive place would say, maybe I should charge less for this. But I don’t think we’re quite there yet.

IRA FLATOW: So you think maybe there’ll be a website that you shop like you shop for a car or a hotel for the best price? I could see the commercials now.

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: A guy comes on and says, we choose from all the MRI sites on the web. And you get to choose. But that seems to be something that might be good.

MARGO SANGER-KATZ: It could be good. And there are real advocates who feel the health care economy is kind of really messed up because people don’t behave like consumers the way that they do in other parts of our economy. On the other hand, if you’re in a terrible car accident and you’re an ambulance and you’re unconscious on the way the hospital, it doesn’t matter how good the website is. You probably are in no position, either to pick the place that you go or to really make any judgment about what kind of medical care you need. If something’s really wrong with you, most people will just listen to what the doctor tells them.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, we’re back at square one. All right. Margot, thank you very much very. It’s a very intersting topic. Margot Sanger-Katz is a health care correspondent for the New York Times.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.