Why Theoretical Physics Says The US Is Ungovernable

12:02 minutes

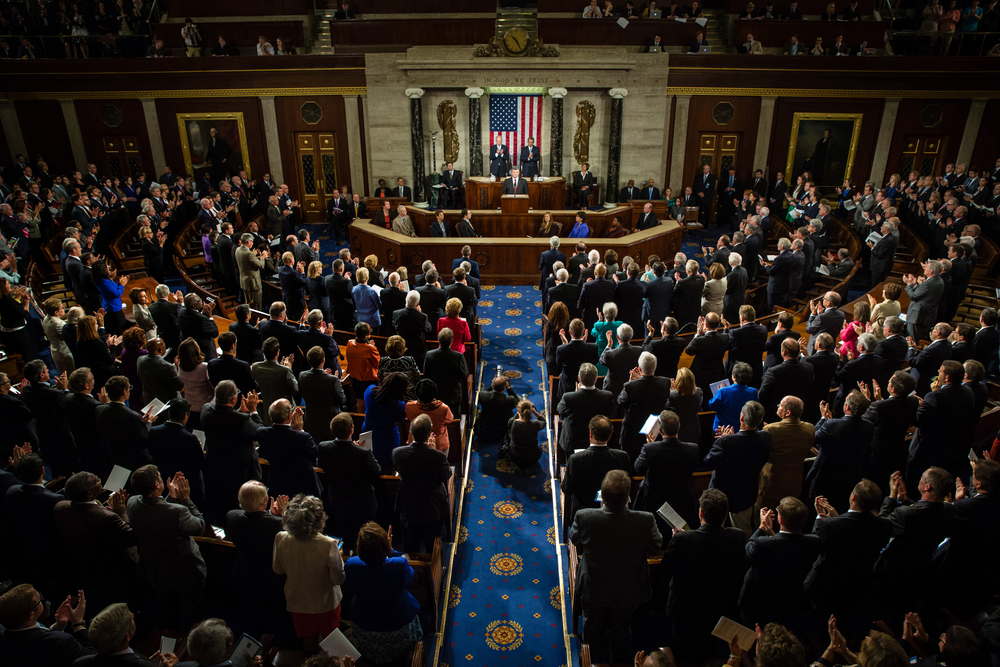

No matter who holds the highest office in the land, it never seems like the U.S. government is working as well as it could be. Our form of government is so intricately woven that it would be impossible for even the deftest efficiency expert to pinpoint the clog (or more likely, clogs) in the system.

But physics can shed some light, says Yaneer Bar-Yam, a physicist and the director of the New England Complex Systems Institute in Cambridge. By applying a special framework borrowed from quantum field theory to convoluted systems like our government and big companies, Bar-Yam can home in on the right amount of relevant information to understand the way the system works, and even what it might do next.

So what happens when you apply this framework to the U.S. government? Bar-Yam says that hierarchical systems, where one person is more or less in charge, buckle under the weight of too much complexity. He joins Ira to discuss what quantum physics reveals: that it’s our political system, not the people themselves, that’s making the U.S. ungovernable.

Yaneer Bar-Yam is president of the New England Complex Systems Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. During President Trump’s campaign he claimed that he was the only one who could fix what was wrong in Washington. But my next guest, a physicist, says that the math of quantum mechanics tells us it’s our form of government– our system– that’s broken, and no single person can fix it.

He says, according to a framework borrowed from quantum field theory, no single person can manage the complexities of our government. Not Trump, not Hillary Clinton, not Bernie Sanders. Our democracy is just too complex now to be governed the way it is. Now, is he right?

My guest, Yaneer Bar-Yam does have a track record. He crunched big data to successfully predict that the Arab Spring would happen. So what does he propose we do? Yaneer Bar-Yam is Director of the New England Complex System Institute, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Welcome to Science Friday.

YANEER BAR-YAM: Pleasure to be here, thank you.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. So how does quantum mechanics help us understand the complexity of something like the US government?

YANEER BAR-YAM: So, it’s a mathematical formalism that was originally developed in quantum mechanics. What it’s really about is the realization that you don’t always have a specific set of quantities that describe a system, but rather you need to think about how the things that you want to describe changes as you zoom in and see more and more detail.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. And you’ve used this math to study complex systems before, right?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Yes. It was transferred from quantum mechanics into the study of phase transitions in materials. So boiling water– it turns out that at a particular point, called the critical point, the structure of the material doesn’t know whether it’s water or vapor. And it’s kind of fluctuating back and forth at all scales.

So there are large fluctuations, and smaller fluctuations. And so, if you think about it as a smooth system, you just don’t describe what’s happening. And you have to think about it by zooming in and seeing progressively more fluctuations that are happening.

IRA FLATOW: So when you apply that framework to the US government, you’re saying that you’re seeing a very complex system that no one person can manage.

YANEER BAR-YAM: Well, it’s not the government itself. It’s what the government is dealing with, right? You can think of the society that we’re part of. You can also think of the world that we’re responding to, and all of the things that are happening all over the world, including domestically and internationally. There is a lot of stuff happening.

And then how do you respond to everything that’s going on? And if you are a policy maker, you want to focus on the largest things that are happening. But what happens if the largest things give way to just slightly less large things? And then there are more things a little bit finer that you have to worry about. And it’s really hard to respond to all of them at once. And that’s what the challenge is.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm, so you’re sort of surrounded by unintended consequences.

YANEER BAR-YAM: Well, so the point of not being able to respond to everything is that everything that you do triggers effects in these other things that are going on in the system. And those are the unintended consequences that people talk about.

IRA FLATOW: Well, but don’t we have a system of checks and balances that are supposed to take care– you know, watch out for each other?

YANEER BAR-YAM: The fundamental challenge is actually that as soon as you have a hierarchical organizational structure, what you’re doing is you’re making the assumption that one person can understand and respond to the most important things that are happening. And in this case– where you have so many very important things that are happening– one person just can’t do that.

IRA FLATOW: So how do you how do you know– I mean, let me go back and ask this question. This wasn’t always the case. From studying your work, I see that there’s sort of an arc of history here, where we started out with simple societies and got them more complex. There was a time when you could govern with a single person?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Yeah. I mean, we know that hierarchical systems have really been very successful over history. You know, we had empires, and kingdoms, and we had companies that were very hierarchical. And, you know, that seemed to work very well. I mean, democracy, as much as we elect– from the, you know– the public elects, we still are electing representatives that are just a few people that are making decisions for the country as a whole. And that worked very well.

And it kind of started falling apart in the 1980s. And by now it should be quite apparent that, you know, these systems that are hierarchical are just not able to deal with the complexity of the world that we’re in.

IRA FLATOW: So what was that tipping point in the 80s?

YANEER BAR-YAM: So what happened during the 1980s is the world– I mean, over the period of the last century, and until today– is that the world became much more interdependent. You know, things happening everywhere in the world, whether it’s in small countries like Kuwait and the Gulf– you know, the Gulf War, or in Japan, or in North Korea. Or, you know, almost anywhere in the world you have events, and they affect everything.

Whether it’s economic events– the financial crisis propagation– whether it’s governance and disruption of social order, or whether it’s diseases. You know, everything is affecting what’s happening everywhere else. So those are the– that’s the functional drivers of what happened in terms of complexity.

IRA FLATOW: OK, so if the hierarchy– and I’m going to look at this visually as a vertical system– is not, working can we more horizontalize it and spread it out and make it work?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Absolutely. And that’s kind of the principle. I mean, if we stick to hierarchies we’re going to fail, but there are other structures that can work. More network distributed organizations. And you can see that there is a cultural shift happening, where people are realizing that how much you rely on leaders is actually causing systems to be less successful. Right?

In the past we would say that, you know, if you had a problem, you put someone in charge. And today that’s just not going to work. And it seems that people realize that. Everything from, you know, how we think about corporations where they’re developing very laterally– functioning and decision making and organizations– to, you know, social movements and how people think about what’s happening in that context.

IRA FLATOW: Well, the buck has to stop someplace in a system. So who would make those tough decisions in a more horizontal situation?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Well, that’s kind of– you’re kind of making the assumption that is really not valid in this regime. I mean, if you think about your brain– I mean, there are– I don’t know– the number of neurons in your brain is somewhere between 10 to the 12th and 10 to the 16th, depending upon who you ask. And there isn’t one neuron that’s telling the other neurons what to do. It’s a collective behavior that really is responsible for how you think about how you decide, and what you do.

And the same thing can, in principle, happen in society. We have to form the organizations that make that work. And there is a lot of experimentation today in that context. But in the public sector it’s much harder to change the organizational structures that we have established by constitution. And shifting the decision making from the existing representative democracy to alternatives that involve many more people in making decisions is a process that we don’t have a formula for.

IRA FLATOW: Are you saying we should go from a republic to a pure democracy? So then everybody has a wider participation?

YANEER BAR-YAM: So voting is a very poor way to combine people’s understanding. It’s not very successful– if you think about it, everyone having one vote doesn’t really take advantage of the differences in what people know and what they can contribute. I mean, your brain is structured so that different neurons are responsible for different kinds of things. And really, the way the brain is structured it’s not just about individuals, but how they’re connected to each other.

So the same kind of thing in society would look like different groups of people that are involved in different kinds of decisions. And the reason why they’re involved in those decisions is that they actually do them very well. And it’s not even an individual trait as much as it is a collective trait of how the system is organized.

IRA FLATOW: We have lobbyists who do make decisions and do them very well, but we don’t think very highly of them. How would this be different?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Well, the problem with that way of thinking is that you really have to have the decisions being evaluated on the basis of their success in doing what we, as a society, would like them to do. And so people don’t think very highly of those decision makers, what we need to do is find out how to evaluate better the decision makers, and put the responsibility in their hands.

IRA FLATOW: And who would be those decision makers?

YANEER BAR-YAM: Well, so that’s a really deep question. And basically, what we have to do is engage as a society in the challenge of identifying not just individuals, but really groups of people that are able to, together, make good decisions. And part of the challenge– if I can add– is to understand that just like we talked about in the other context, that there are different things happening at different scales of the system.

So some decisions are not relevant to everybody, they should be done more locally. And some decisions should be done more globally. And understanding how to separate the different kinds of decisions to different groups of people is important.

IRA FLATOW: And how do we begin this process?

YANEER BAR-YAM: So, to great extent, I think that we’re beginning to engage in that. I mean, this is something that is being done intentionally in companies that are adopting more distributed organizational structures, and really have been adopting them since the 1980s. But the societal engagement in this is happening in the form of people to caring about, and thinking about, and talking about decisions that are being made in policy. What we have to do, however, is to create mechanisms by which that participation translates into actual decision making, rather than shifting it once again to one person, or a few people who have that authority.

IRA FLATOW: Yaneer Bar-Yam is director of the New England Complex Systems Institute, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

YANEER BAR-YAM: Great to talk with you.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.