Blood Clots Linked To COVID-19 Are Raising Alarm

11:40 minutes

This story is a part of Science Friday’s coverage on the novel coronavirus, the agent of the disease COVID-19. Listen to experts discuss the spread, outbreak response, and treatment.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has primarily been considered a respiratory virus, causing acute problems in the lungs. But doctors around the world have recently been reporting unusual blood clotting in some COVID-19 patients. The exact cause of these blood clots isn’t yet known—there are several interacting biological pathways that all interact to create a blood clot. One theory is that the clotting is related to an overactive immune response, producing inflammation that damages the lining of small blood vessels. Other theories point to the complement system, part of the overall immune response.

Ira speaks with hematologists Jeffrey Laurence of Weill-Cornell Medicine, and Mary Cushman of the University of Vermont Medical Center about the unusual clotting, how it impacts medical treatment, and what research they’re doing now in order to better understand what’s going on in patients.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Dr. Jeffrey Laurence is a professor of Medicine in the Division of Hematology-Oncology at Weill-Cornell Medicine and an attending physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York, New York.

Dr. Mary Cushman is a hematologist at the University of Vermont Medical Center and a professor of Medicine and Pathology in the Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont in Burlington, Vermont.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The COVID-19 epidemic has become known as a respiratory disease targeting the lungs of infected people. But doctors are also seeing strange responses to the virus in other parts of the body, including the blood. Doctors around the world are reporting unusual blood clotting in a large proportion of hospitalized coronavirus patients.

Joining me now to talk about what they are seeing and how medical workers are responding to the collapse are two hematologists, Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, professor of medicine in the division of hematology oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine, and attending physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital; and Dr. Mary Cushman, a hematologist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, professor of medicine, and pathology at the Larner College of Medicine at UVM in Burlington, Vermont. Welcome both of you to Science Friday.

JEFFREY LAURENCE: Thank you.

MARY CUSHMAN: Thanks. It’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let me begin with you, Dr. Laurence. Early on, you noticed some unusual clotting in patients with the coronavirus. Please tell us about that.

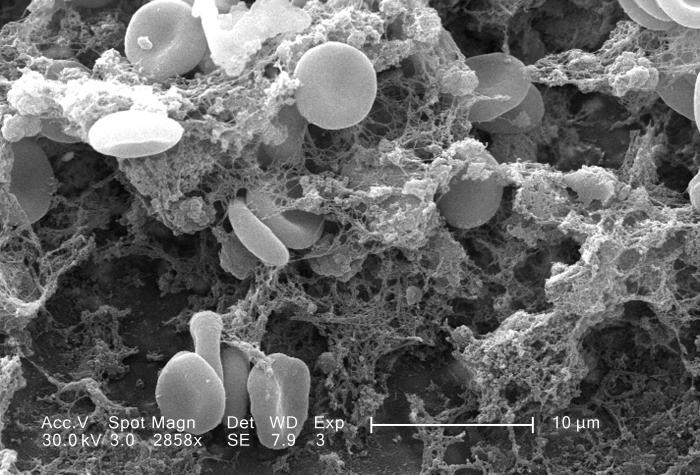

JEFFREY LAURENCE: One of the very first patients that I saw was a young man, and this was early in March, who had symptoms for about 10 days, and then got very sick, and came into the hospital, and was put on a ventilator. And about three days into his hospitalization, one of the nurses noted that he had some very strange rashes on his bottom and called a dermatologist, who did a biopsy, and they found out that it was a very unusual kind lesion, one that they typically don’t see, that had small blood vessels clotting.

And there were so many clots and so many small vessels that on his backside, you could basically see the imprint of what small microvascular cells would look like right under the skin. And when they sent it to pathology, the pathologist recognized that it was something, some unusual kind of clotting that I had studied in some very unusual cases of rare disorders and wondered what was that doing in a patient with COVID, particularly young men.

And so we evaluated it for certain proteins that were associated with inflammation and associated with the immune system complement and found out that they were deposited there. And I thought that was just very, very strange because it’s not something that we’re used to seeing in the intensive care unit setting, certainly not something we’re used to seeing with other viruses. That was, like, on an afternoon, say, on a Wednesday and later that night, I get a phone call from the autopsy room saying that they have a patient who’d come in and just died and had some unusual lesions on his skin. And they biopsied them and called me about them.

And so, basically, we said we have a pattern here. And in fact, over the next week, we found three more identical cases. And this was a clue that something funny was happening, and that kind of led us to start investigating what was happening to the clotting system and what was happening to the immune system in these patients, and could they be intimately linked?

IRA FLATOW: How common is this is? I know that we hear other cases in other hospitals. Is this is something doctors are watching out for?

JEFFREY LAURENCE: The vast majority of people who get infected with the coronavirus, who get COVID-19, either don’t have symptoms or very mild, don’t have to worry about this. But in the severe cases, the ones that filled up our adult emergency room and then filled up our pediatric emergency room with adults are unusual because of the level of clotting.

So typically, when a patient comes into the intensive care unit, they’re often put on prophylactic blood thinners to prevent them from getting clots because they’re going to be, basically, lying isolated in intensive care unit, and they have an infection that will cause their blood to clot a bit more, so they’re given prophylactic clotting medicines. But we were seeing clotting on the prophylactic and clotting medicines. So we increased the doses in some of these patients. And some of them were still clotting.

And then we put them on full doses of anticlotting medications, like heparin, that certainly ought to take care of the problem, and we were seeing clotting anyway. In fact, one of the things that made me so cognizant of the problems that we were seeing in our hospital but was not specific to our hospital was when a kidney doctor was quoted on the front page of the New York Times saying, we’ve gotten this disease all wrong. We’re not going to run out of ventilators. We’re going to run out of dialysis machines because we’re clotting off the filters of our dialysis machines. And these are patients who are on full doses of anticoagulation. And then I knew we had a real issue, and this is something different than the kind of standard clotting that we were seeing.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Cushman, what would be causing this kind of clotting in these patients?

MARY CUSHMAN: The first piece of news that I learned in the medical literature was a paper out of Wuhan, China that suggested patients have high levels of biomarkers of clotting, namely a biomarker called D-Dimer, which is a marker of the generalized level of pro-clottability, if you will, within a person. And this is accompanied by high levels of inflammatory biomarkers as well.

So there’s really three key points that come out of this that it seems that in some patients who have more severe disease requiring hospitalization, we have this inflammatory process that is triggered, and we don’t fully understand the reason for the triggering of it. Some people believe that it’s because the virus is affecting and disrupting the inner lining of blood vessels in small and large blood vessels and disrupting that protective barrier that lines the inner lining of the blood vessels and that release of substances. That can allow the clotting system to be triggered.

And this process is really fascinating because it’s not been seen with the same pattern of these biomarker changes that we can measure in the lab. This has not been seen in other viral infections or bacterial infections. It’s very different than what we’re used to seeing.

And so the second big finding that I noticed in the literature was that patients in the hospital who have this high level of D-Dimer tend to have worse outcomes. They have a higher mortality compared to other patients and a higher likelihood of requiring a transfer to the ICU and have respiratory failure. And so it raises the possibility, as Dr. Laurence alluded to, that thinning the blood to try to dampen down the pro-clotting effects could be beneficial to patients.

And so the third point that came out pretty early in the literature out of China was that patients who had higher levels of D-Dimer, representing this thromboinflammatory drive seemed to benefit the most from these low doses of anticoagulation prophylaxis, if you will, that Dr. Laurence referred to. And so it really raises the question of how we can preserve the outcomes of patients with biomarkers-based strategies that might provide escalated doses of blood thinner in people who even don’t have evidence of clots at the time.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting and mysterious, Dr. Laurence. Are you seeing any pattern to who develops these clots? Any pattern with regard to age, or blood type, race, anything that might predict who’s going to be throwing off these clots?

JEFFREY LAURENCE: Sure, so as Dr. Cushman said, we all think that rising D-Dimers is a bad thing, but how high they should rise and what the trajectory of that rise needs a controlled clinical trial. But we have kind of clinical points that can help you judge who might be more at risk for rising D-Dimers and more clotting, one of them is obesity. So obesity, patients with diabetes, patients with hypertension tend to have faster rises in D-Dimers.

And women, apparently, women are much less prone to a severe outcome and have less serious diseases for the same ICU admission than men. And that’s curious. So what’s protecting women to some extent, and what is harming people of older age, people with obesity, people with diabetes, and people with hypertension?

And in fact, a protective factor for women occurs in all ages. So there’s one very large study of over 16,000 patients being conducted in hospitals in the United Kingdom, which shows that this protection of female sex occurs in every age range they look, from 50 to over 90 years of age.

And one of the characteristics that appears to protect women and may be harmful in terms of the setting of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension is that patients with pre-existing diabetes, obesity, and hypertension have higher levels of this, I mean, protein substances called “complements” and have higher levels of baseline without the COVID of these inflammatory components that Dr. Cushman was talking about. And they have higher levels of D-Dimers. So they’re kind of at a set point. If you’re a male, older age, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, to getting these occurrences.

Another thing that’s peculiar and it’s come out of a large study from New York City of 5,700 patients, New York City and its surrounding 10,000 to 16,000 United Kingdom study, is that why is it that people with HIV, for their numbers, tend to be getting less severe disease? And why is it with patients with cancer– if you make a list of the 10 risk factors for getting disease, cancer is at the very lowest risk factor, barely statistically significant, with the relative risk of 1.1.

So what’s so special about cancer patients? And what’s so special about HIV? And our hospitals like to say that we just take great care of cancer patients, and we’re very good at social distancing. We use television, and so forth.

But I think it’s something more than that. And I think it’s telling us something about what’s bad at having high levels of pre-existing complements and what’s good about having some level of immunosuppression. Perhaps that’s what’s driving cancer as less of a risk factor. Perhaps that’s what’s driving patients with HIV, even when they’re on their HIV medicines, because they still have defects in their immune system.

And particularly, they have defects in the immune system involving their innate immune system, which complement is part of. So that’s a long-winded explanation to say that we don’t know what’s the driving forces, as Dr. Cushman said, to settle this clotting [INAUDIBLE] We know that there are three pathways that are involved. There’s a clotting pathway. There’s the inflammation pathway.

And there’s a complement pathway. And all of them can turn on each other. So you have this insidious positive feedback loop between clotting, and the immune system with inflammation, and the immune system with complement. And if you can’t shut it off, then you may need to intervene at more than one pathway, then you’re in a lot of trouble.

And in terms of is it the virus that sets it off at the very first and what’s so special about COVID, well, one of the things that we and others have shown in early papers is that the virus itself has a protein on its surface, the little spikes that you’ve seen pictures in the newspapers, which can directly bind to a complement component. It can start causing platelets to aggregate. It can start initiating clotting factors.

So the virus itself may set this off. And if you can’t control it for whatever reason, you’re kind of stuck in this insidious loop. And so that’s why clinical trials are so important, why we need to try multiple interventions, not just antivirus drugs, not just blood-thinning drugs, but also anti-complement drugs and anti-inflammation drugs.

IRA FLATOW: What do people need to know about the clotting? You know, they tell us when you’re a certain age, you should take a little mini aspirin to prevent the clotting, possibly preventing strokes. Anything like that to be doing here?

MARY CUSHMAN: Yeah, I would say, for this disease, the type of clotting that’s going to be most common, apart from the clotting that seems to be tightly linked to the disease itself, like these microclots that might form in the lungs, or kidneys, or on the skin, the most common type of abnormal clotting that’s going to occur in patients with this infection is deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

We also call that “venous thrombosis.” And these are clots in the larger veins of the legs that are returning blood back to the heart. And the danger of those clots is that people can break off and travel to the lungs, which is pulmonary embolism. That’s a life-threatening type of abnormal clot.

This is the third leading vascular disease after a heart attack and stroke, so it’s very important, but the public awareness is pretty low on it, so only about 50% of people even know what it is. And any infection, any acute infection, or any hospitalization can raise the risk of venous thrombosis. And COVID seems to be more strongly triggering of these venous thrombosis events. The jury is a little bit out in terms of what the exact incidence is, but it’s felt that it’s higher. So prevention is really important.

So the average person should just be aware of this. And we don’t yet know if this is also affecting people who are sick at home with COVID. You know, most people with this infection don’t get hospitalized. And so if you’re sick at home with it, for example, being aware that venous thrombosis could occur is important, and that means knowing the symptoms, which are leg pain and swelling, sometimes discoloration of the legs, chest pain and shortness of breath, and also being sure that if you have symptoms like this that you don’t ignore it and that you seek medical care.

We’re finding that a lot of people are afraid to come to hospitals with acute illnesses because they’re afraid they’ll catch the infection in the hospital. But, really, being aware that this disease exists and being aware that it can cause death at the worst, it’s important to recognize the other risk factors we’ve talked about, like obesity and older age are often risk factors for venous thrombosis. So if you have those conditions, you want to be especially cautious about it.

IRA FLATOW: In case you just joined us, I’m Ira Flatow, and you’re listening to Science Friday from WNYC studios. You know, this has been called “the novel coronavirus,” and it seems like there’s still so much we don’t know about it, isn’t there?

MARY CUSHMAN: Oh, absolutely. It’s almost endless the question that could be posed. And I think that, in hematology research, the research community is supercharged right now to try to do our part to help answer some of these really critical questions, getting back to this idea of anticoagulation in hospitalized patients. If we were to just start anticoagulating every patient who comes in the hospital, we would cause a lot of bleeding complications, and we don’t know really whether that’s the right intervention. Maybe an intervention toward the complement system is better or an anti-inflammatory approach is better.

So we don’t really know the answer, yet we’re seeing these kinds of protocols arise in hospitals. And it’s good because people are doing what they think is best, but doing what you think is best for your patient isn’t always the right thing. And so that’s where the role of research comes in and really trying to, in a supercharged way, proceed to launch major research efforts to answer these questions.

So that’s kind of what’s driving us in our clinical trial to say, OK, let’s pause here for a moment and figure out, really, get the evidence that we need to understand if this is the best approach or not. Trying to solve these questions of racial disparities, is it all due to socioeconomic factors? Or is there a biological difference in the coagulathopy of these patients that is contributing to the worst outcome? You know, we really don’t know.

And we can’t get these answers without research. So for your listeners who are science-geeky people, the scientific process is laid out right here for you to see, and I think it’s a really exciting time for answering new questions. And maybe we’ll find out answers to questions that relate to other diseases as well.

IRA FLATOW: We have run out of time. I’d like to thank both of you, Dr. Mary Cushman, hematologist at the University of Vermont Medical Center, professor of medicine and pathology at the Larner College of Medicine at UVM in Burlington Vermont; Dr. Jeffrey Laurence, professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology Oncology at Weill Cornell Medicine and attending physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital. Thank you both for taking time to join us today.

JEFFREY LAURENCE: You’re very welcome.

MARY CUSHMAN: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2020 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.

Ira Flatow is the host and executive producer of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.