Kitty’s Tongue, Under The Microscope

A magnified look at a cat tongue reveals the serrated edges that Fluffy uses to clean herself, and rasp meat from bone.

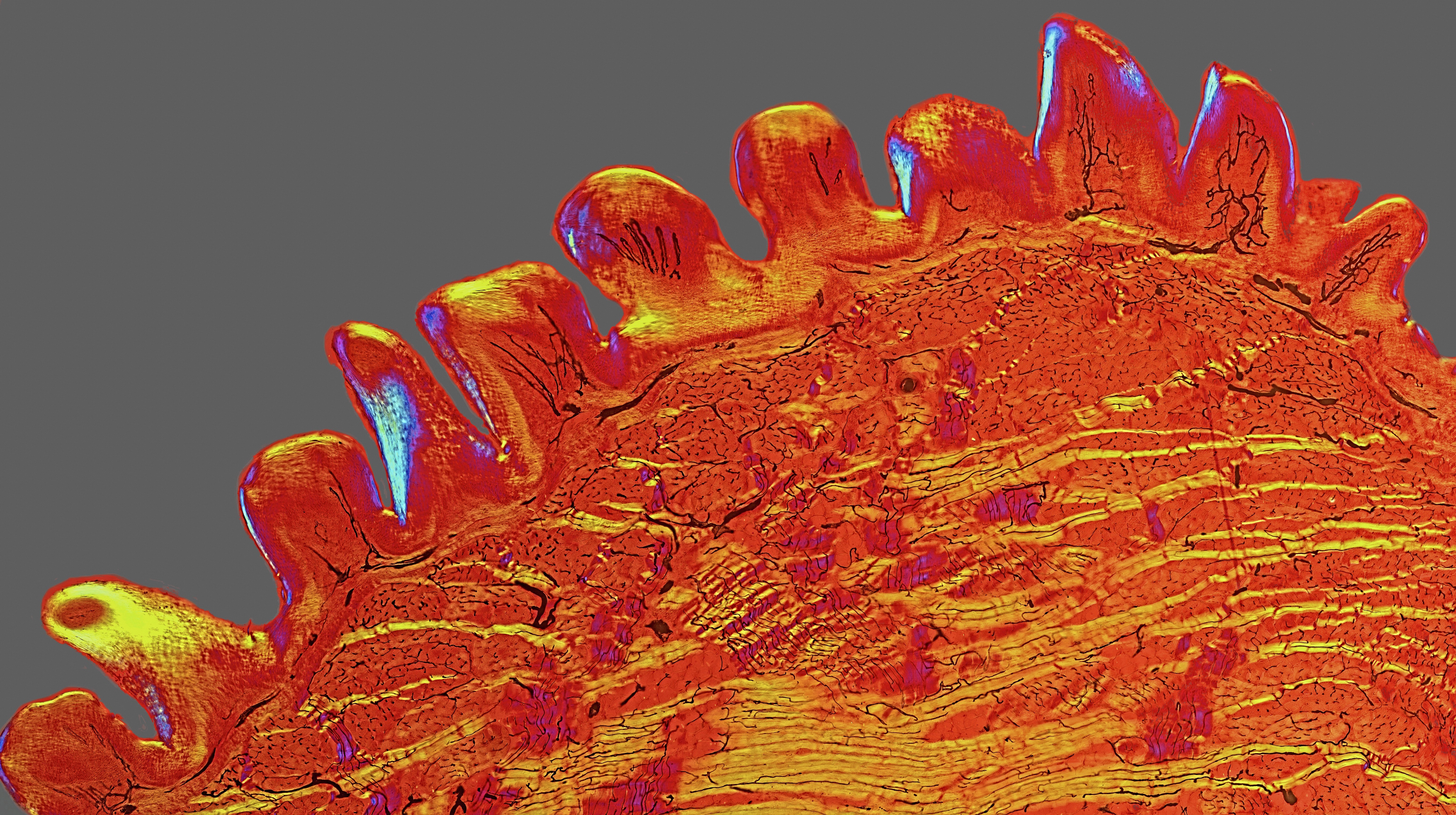

A composite image of a section of cat tongue plated on a microscope slide, dating back to the 1890s. The yellow streaks are horizontal muscles, the sparse purple streaks are vertical muscles, and the black squiggles are capillaries. Those blue-purple spots on the tongue's serrated edge represent polarized light interacting with keratin. Image by David Linstead

You’re looking at a 3 mm-wide section of a cat tongue more than a century old. David Linstead’s captivating image was a winner in the 2015 Wellcome Image Awards, run by the Wellcome Trust, a biomedical charity in London.

The picture is actually a composite of 30 polarized light micrographs, or photographs taken with a digital camera and a microscope. A retired cell biologist, Linstead used microscopes professionally as a research tool, and later formed his “hobby addiction” after purchasing one, then another, and still more microscopes on eBay (also his go-to source for specimen-plated slides like this one). His particular interest is in combining modern illumination techniques with vintage slides dating from 1860 to 1910, the heyday of slide-making.

“The original person who made this slide likely had no thought of how it would be used in 100 years’ time,” says Linstead, who estimates that it dates back to the 1890s. “But when I saw it, I immediately knew it had great potential.”

[When astronauts see this, they know they’re not too far from home.]

The promise lay in the way the slide was prepared. It wasn’t stained, for one, which allowed the cross-section’s true colors to be observed with polarized light—a feature of most cutting-edge microscopes of the Victorian age. Those yellow streaks, for instance, are horizontal muscles, and the sparse purple ones are muscles that run vertically. (For a closer look, click on image here, and use the zoom-in tool.)

Furthermore, the original tissue had been injected with a dye—probably a solution of iron salt in warm gelatin, Linstead surmises—to make the capillaries, seen here as black squiggles, apparent. (The only alteration Linstead made to the image was to Photoshop the background gray, because the original magenta “didn’t go well with the rest of the slide.”)

Colors aside, the serrated ridge may be the most intriguing aspect of this picture. Those rough bumps, or papillae, are the reason that a kitty’s tongue feels like sandpaper when it licks you. When a cat grooms herself, the papillae act like a comb to remove dirt and loose hair. But they also serve a grislier purpose: rasping meat off of bones. Fluffy might look sweet, but Linstead’s striking image is a reminder that the cat napping on the couch is a fierce predator. “Sometimes,” said photo contest judge Fergus Walsh, a medical correspondent for the BBC, “images that show nature in extreme close-up are both beautiful and illuminating.”

Alisa Opar is the articles editor at Audubon magazine and the Western correspondent for OnEarth.