Truth, Educated Guesses, and Speculations in ‘Interstellar’

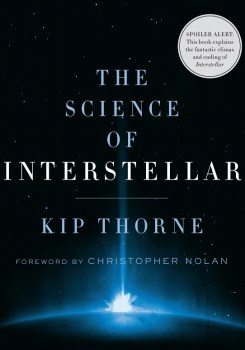

An excerpt from “The Science of Interstellar.”

The following is an excerpt from The Science of Interstellar, by Kip Thorne.

The science of Interstellar lies in all four domains: Newtonian, relativistic, quantum, and quantum gravity. Correspondingly, some of the science is known to be true, some is an educated guess, and some is speculation.

To be true, the science must be based on well-established physical laws (Newtonian, relativistic, or quantum), and it must have enough basis in observation that we are confident of how to apply the well-established laws.

In precisely this sense, neutron stars and their magnetic fields are true. Why? First, neutron stars are firmly predicted to exist by the quantum and relativistic laws. Second, astronomers have studied in enormous detail the pulsar radiation from neutron stars. These pulsar observations are beautifully and accurately explained by the quantum and relativistic laws, if the pulsar is a spinning neutron star; and no other explanation has ever been found. Third, neutron stars are firmly predicted to form in astronomical explosions called supernovae, and pulsars are seen at the centers of big, expanding gas clouds, the remnants of old supernovae. Thus, we astrophysicists have no doubt; neutron stars really do exist and they really do produce the observed pulsar radiation.

Another example of a truth is the black hole Gargantua and the bending of light rays by which it distorts images of stars (Figure 3.3). Physicists call this distortion “gravitational lensing” because it is similar to the distortion of a picture by a curved lens or mirror, as in an amusement park’s fun house, for example.

Einstein’s relativistic laws predict, unequivocally, all the properties of black holes from their surfaces outward, including their gravitational lensing. Astronomers have firm observational evidence that black holes exist in our universe, including gigantic black holes like Gargantua. Astronomers have seen gravitational lensing by other objects, though not yet by black holes, and the observed lensing is in precise accord with the predictions of Einstein’s relativistic laws. This is enough for me. Gargantua’s gravitational lensing, as simulated by Paul Franklin’s Double Negative team using relativity equations I gave to them, is true. This is what it really would look like.

By contrast, the blight that endangers human life on Earth in Interstellar is an educated guess in one sense, and a speculation in another. Let me explain.

Throughout recorded history, the crops that humans grow have been plagued by occasional blights (rapidly spreading diseases caused by microbes). The biology that underlies these blights is based on chemistry, which in turn is based on the quantum laws. Scientists do not yet know how to deduce, from the quantum laws, all of the relevant chemistry (but they can deduce much of it); and they do not yet know how to deduce from chemistry all of the relevant biology. Nevertheless, from observations and experiments, biologists have learned much about blights. The blights encountered by humans thus far have not jumped from infecting one type of plant to another with such speed as to endanger human life. But nothing we know guarantees this can’t happen.

That such a blight is possible is an educated guess. That it might someday occur is a speculation that most biologists regard as very unlikely. The gravitational anomalies that occur in Interstellar, for example, the coin Cooper tosses that suddenly plunges to the floor, are speculations. So is harnessing the anomalies to lift colonies off Earth.

Although experimental physicists when measuring gravity have searched hard for anomalies—behaviors that cannot be explained by the Newtonian or relativistic laws—no convincing gravitational anomalies have ever been seen on Earth.

However, it seems likely from the quest to understand quantum gravity that our universe is a membrane (physicists call it a “brane”) residing in a higher-dimensional “hyperspace” to which physicists give the name “bulk”; see Figure 3.5. When physicists carry Einstein’s relativistic laws into this bulk, as Professor Brand does on the blackboard in his office (Figure 3.6), they discover the possibility of gravitational anomalies—anomalies triggered by physical fields that reside in the bulk.

We are far from sure that the bulk really exists. And it is only an educated guess that, if the bulk does exist, Einstein’s laws reign there. And we have no idea whether the bulk, if it exists, contains fields that can generate gravitational anomalies, and if so, whether those anomalies can be harnessed. The anomalies and their harnessing are a rather extreme speculation. But they are a speculation based on science that I and some of my physicist friends are happy to entertain—at least late at night over beer. So they fall within the guidelines I advocated for Interstellar: “Speculations . . . will spring from real science, from ideas that at least some ‘respectable’ scientists regard as possible.”

Throughout this book, when discussing the science of Interstellar, I explain the status of that science—truth, educated guess, or speculation.

Of course, the status of an idea—truth, educated guess, or speculation—can change; and you’ll meet such changes occasionally in the movie and in this book. For Cooper, the bulk is an educated guess that becomes a truth when he goes there in the tesseract; and the laws of quantum gravity are a speculation until TARS extracts them from inside a black hole so for Cooper and Murph they become truth.

For nineteenth-century physicists, Newton’s inverse square law for gravity was an absolute truth. But around 1890 it was revolutionarily upended by a tiny observed anomaly in the orbit of Mercury around the Sun. Newton’s law is very nearly correct in our solar system, but not quite. This anomaly helped pave the way for Einstein’s twentieth-century relativistic laws, which—in the realm of strong gravity—began as speculation, became an educated guess when observational data started rolling in, and by 1980, with ever-improving observations, evolved into truth.

Revolutions that upend established scientific truth are exceedingly rare. But when they happen, they can have profound effects on science and technology.

Can you identify in your own life speculations that became educated guesses and then truth? Have you ever seen your established truths upended, with a resulting revolution in your life?

Excerpted from The Science of Interstellar, by Kip Thorne. Copyright © 2014 by Kip Thorne. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

Kip Thorne is a theoretical physicist; executive producer and science advisor on Interstellar (Paramount, 2014); and author of The Science of Interstellar (Norton, 2014), based in Pasadena, California.