How Hawaiian Voices Add To The Conversation On Deep Sea Mining

A Hawaiian elder discusses what’s at stake for Indigenous Hawaiians when we disturb the ocean floor.

Hulopo'e Bay, Pu'u Pehe, and Shark's Bay in Lāna‘i, where Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala is from. Credit: Shutterstock

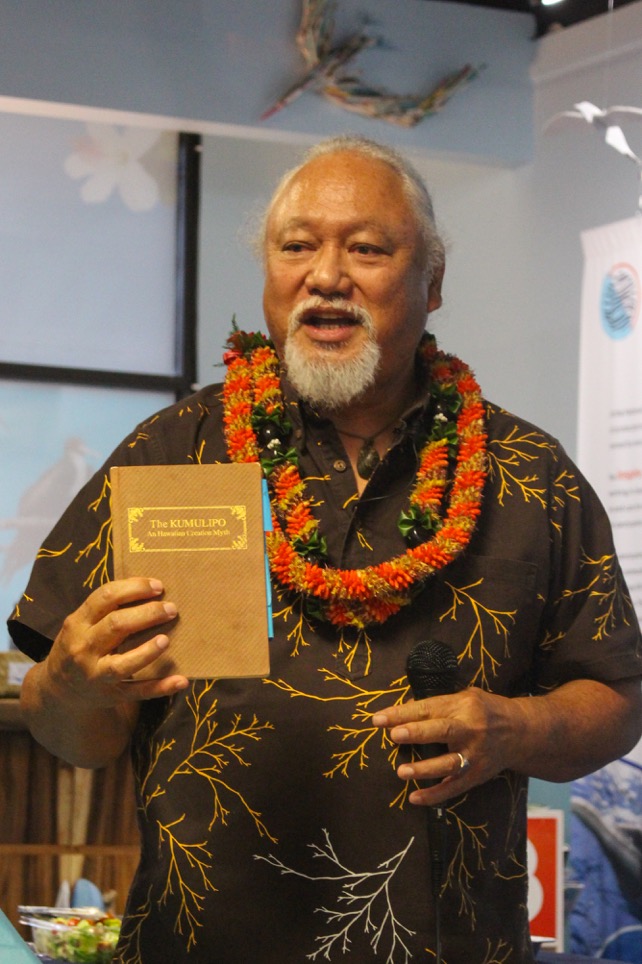

For Hawaiian conservationist, politician, and elder Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala, there’s no question that life began in the ocean.

A seventh-generation Lānaʻian, Kahoʻohalahala grew up knowing the Hawaiian creation chant, called the Kumulipo. “In the Kumulipo, we emerged from the deep sea. Our eldest ancestor, the first creature to be formed, is the ‘ukuko’ako’a, which is the coral polyp,” Kahoʻohalahala explains. According to the chant, the flower-like polyp was followed by larger marine creatures like fishes, whales, and sharks. Then came birds, land mammals, and lastly, humans.

“We the people, in our traditional chant, don’t arrive until much later in the creation of the space that we call Honua, the Earth,” Kahoʻohalahala says.

“The cultural practices that had been a part of our people for millennia have always been in the vein of ecosystem protection for resources, replenishment, restoration,” he adds. “As a result, we would be recipients that will be subsisting and sustaining our own cultural ability to live.”

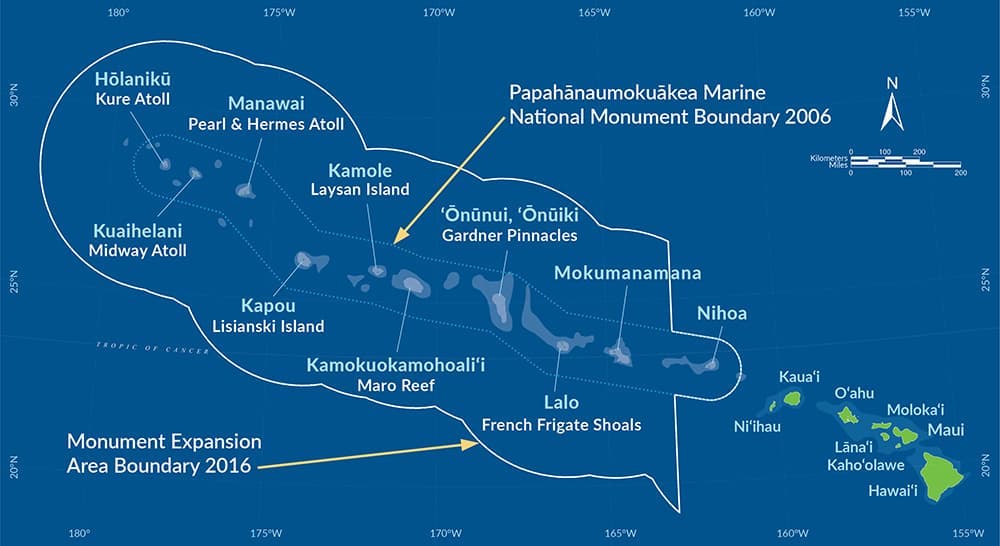

Central to that ethos is protecting the reefs and remote islands around Hawai’i—a goal that Kahoʻohalahala has spent a lifetime advocating for. In 2006, Kahoʻohalahala met with the Obama administration to establish the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument—an over 582,000 mile stretch of land and sea in the Pacific Ocean that includes small islands, atolls, coral reefs, shoals, and seamounts. As a UNESCO World Heritage Site, you can only access the area with a permit, and mining, drilling, and anchoring on coral reefs is prohibited.

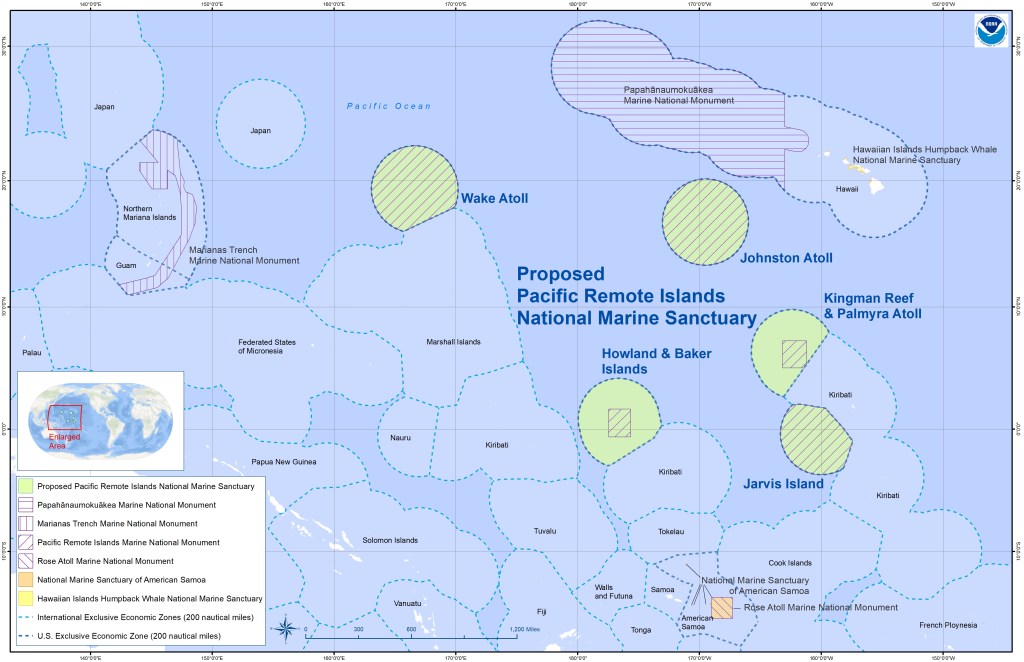

Now the Biden-Harris administration is discussing creating an even larger sanctuary zone that would encompass the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, along with several other currently unprotected atolls and islands. The sanctuary designation would create another layer of protection and “stability,” Kahoʻohalahala says, noting that these national monuments can be vulnerable from administration to administration.

This move is crucial, Kahoʻohalahala says, as the number of marine creatures that are unique to the area face a new potential danger.

Deep sea mining has been a growing topic of conversation amid Hawaiians’ push for more oceanic protections. In the past week, international talks around regulating deep sea mining practices have ended with neither a greenlight for deep sea mining to begin nor a formalized discussion on marine protections.

“To put it bluntly, everything is at stake,” says Kahoʻohalahala.

Deep-sea mining is the process of extracting mineral deposits from the ocean floor. The technology is still relatively new, but currently the process involves driving bulky tractors 200 meters below the surface. The vehicles scrape up the top few inches of the ocean floor and send the sediments they vacuum up to a ship, where they separate out the little metallic nodules that contain manganese, cobalt, nickel, and copper. The remaining sediment gets flushed back down.

Demand for these metals is on the rise because they’re the building blocks for green energy technologies like e-bikes, electric cars, wind turbines, and solar panels. In 2021, the International Energy Agency declared in a report that achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 would require six times more minerals than we currently have.

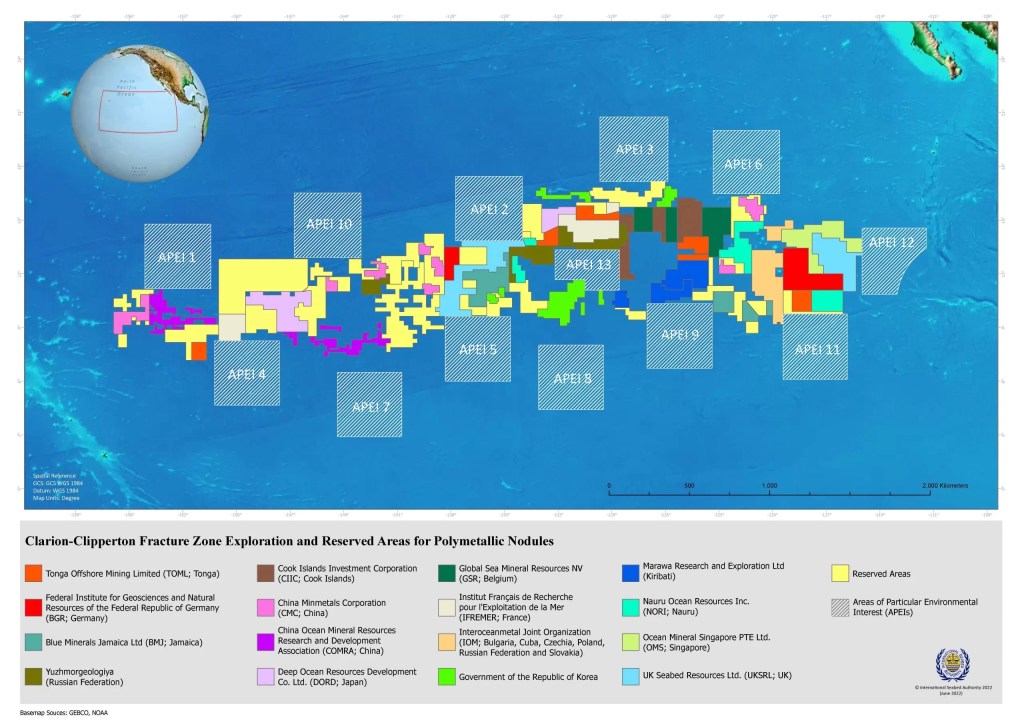

A number of countries (like China, Russia, South Korea, India, Britain, and the small nation of Nauru) have all taken an interest in mining a mineral-rich area of the ocean called the Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone (CCZ), which begins 500 miles south of Hawai’i and is over 3,000 miles long.

In July, several nations convened in Jamaica for the United Nations’ Council of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) to discuss whether or not to begin handing out commercial mining licenses. Facing pushback from activists and countries like Costa Rica, Chile, and France, the ISA decided to delay all contracts until 2025 while they establish firm regulations.

Meanwhile, Hawai’i residents continue to voice their concerns about how all this could potentially impact the waters around where they live. Like other marine scientists, Donald Kobayashi, a biologist with NOAA who moved to the islands about 40 years ago, wonders about the impacts of deep sea mining on the seafloor. He notes that “the ocean can be a little more resilient than we think,” but worries about how large plumes of water coming off the mining ships could affect small deep sea creatures. He says that organisms like the plankton he researches “aren’t going to cope well with suspended material in the water. They’re just used to clear, blue ocean, so it’s going to wipe out a large swath of the water column for these delicate creatures.”

“Even though many people may describe it as a desert, that there’s nothing there, it’s a pretty rich and diverse ecosystem on the abyssal seafloor,” he says. “That shouldn’t be downplayed.”

And for Kahoʻohalahala, the tiny deep sea organisms that live on the seafloor are just as important to our own existence, too. “We’re talking about zooplankton, phytoplankton,” says Kahoʻohalahala. “They’re also part of the creation of oxygen… the ocean provides that second breath of air that we all breathe, and then the terrestrial air areas provide the first breath of air.”

Mining companies say that deep sea mining is less destructive than land-based mining, and that the minerals have to come from somewhere. “We have a whole world demanding we deal with climate change,” managing director Kris Van Nijen of Global Sea Mineral Resources told NPR. “There is not one solution that does not impact biodiversity that actually helps to mitigate climate change.”

Scientists will likely continue to debate this as ISA’s 2025 deadline to revisit the issue looms closer; meanwhile, Kahoʻohalahala says the ones who have largely been left out of the conversation are the Indigenous people who live closest to these mining zones and will be dealing with the potential fallout.

“The United States is beginning to acknowledge that the Indigenous people have been left out of a lot of areas,” Kahoʻohalahala says. “It would be within our interest as Indigenous people to implement relationships that we have with the federal and state governments to support Indigenous participation, inclusion, equity, justice, and all of that as we move forward, and then become managers… of these places which have connections to us.”

Gretchen Smail was Science Friday’s 2023 Audience Engagement Intern. She is currently studying health and science journalism at CUNY’s Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism, where she writes about poverty, reproductive rights, and climate solutions. If she’s not at her computer, Gretchen can be found exploring coffee shops, learning how to embroider, and rock climbing.

Emma Lee Gometz is Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. She’s a writer and illustrator who loves drawing primates and tending to her coping mechanisms like G-d to the garden of Eden.