A Geological Tour From 30,000 Feet Up

10:13 minutes

Peering out the window on a cross-country flight, you can watch the short grass prairies of the Midwest transition into the ragged ranges of the Rocky Mountains. But identifying the specific geological features with more precision can be much trickier.

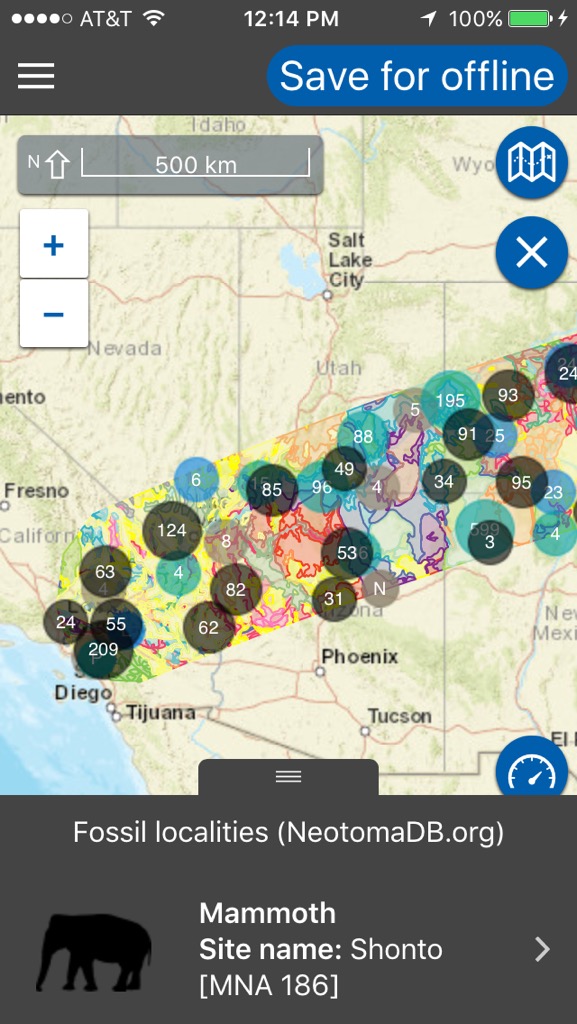

Can you spot the signs of different crustal fractures? Can you tell a meandering river from a braided river? Well, no surprise, there is now an app for that.

Geologist Amy Myrbo, co-creator of the Flyover Country app, says she was inspired by the view from her plane window.

“The window seat was the Google Earth of the past,” Myrbo says. “It’s an amazing view and this is really what got us started thinking about how we could use that window seat as a great way to get people engaged with the geoscience.”

The app, which is available for both iOS and Android, uses a combination of WiFi and GPS. Before taking off, Myrbo suggests loading your city of departure and destination. The app then pulls information about geographic sites within several hundred miles of your travel path and saves it to your phone so you can use the app without purchasing in-flight WiFi.

“It uses your GPS, which is completely legitimate in airplane mode,” Myrbo says.

Manmade objects are easier to see than geologic formations, according to Myrbo.

“Irrigation and crop land and dams … and you can see what what cities you’re flying over,” she says. “There are of course geologically a lot of fantastic things like volcanoes and glaciers and mountain ranges and huge rivers.”

The app also uses information from Wikipedia to give users some background information on the formations they can see.

“There are a huge amount of articles about physio-geographic features and geologic features all over the world, really. Because the app works worldwide, it’s not just not just US or North America and those articles are of course of varying quality, but they tend to be pretty good and they reference scientific literature and tell you a lot about the history and formation and connections between that geology and somewhere else.”

Amy Myrbo is a researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m Ira Flatow. I have been doing lots of traveling this year, but I hate the boredom of flying. But one thing that makes it all worthwhile is spotting something cool outside of the window down below, like the Grand Canyon, or maybe Mount Saint Helens, a giant wind farm. But being so high up, it can be hard to figure out what you’re looking at.

Well, my guest is here to help you out. She’s co-creator of a new app called Flyover Country. The app is Flyover Country, and it pinpoints the geological features that you’re flying over. Yes! And you can even track spots where dinosaur bones have been discovered.

Amy Myrbo was a researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Welcome to Science Friday.

AMY MYRBO: Thanks so much, Ira. I grew up watching you on “Newton’s Apple” on KTCA, in Saint Paul. Now you’re dating me and you’re–

[LAUGHTER]

AMY MYRBO: Are we dating now? Sorry.

IRA FLATOW: Do you always try to get a window seat on a flight like I do?

AMY MYRBO: Absolutely. I will push people out of the way to get that window seat.

IRA FLATOW: You do, huh? Well, haven’t gotten that bold yet, but I’m thinking about it. And did the geologists study the ground this way? Is this a practical way to do it?

AMY MYRBO: Absolutely. Before Google Earth, this is how we did it, right? We had some air photos and we could travel with those in our laps. But really, the window seat was the Google Earth of the past. it’s? An amazing view, and this is really what got us started thinking about how we could use that window seat as a great way to get people engaged with the geoscience.

IRA FLATOW: Well I can’t wait to– I already downloaded the app. Flyover Country, is it on both platforms or just–

AMY MYRBO: That’s right, both Android and iOS.

IRA FLATOW: You can get it. I can’t wait to start. And let me see, you start the app, you’re up in the sky. And does the app follow you as you fly over stuff?

AMY MYRBO: Well so ideally, you would load your path while you’re still on Wi-Fi on the ground. So what you would do is click on the city of your departure and your destination. You could also click on multiple cities. Say if you were taking a road trip or a hike, there’s a mode for that as well– so not just for flying.

But you would click on your departure airport and the arrival airport, and then say load path. Then the app will go out to a number of geoscience databases and pull down the information within sort of a strip of a couple hundred miles around your path. And then, you can save that to your phone, and you have it offline without buying in-flight Wi-Fi, or without having data.

IRA FLATOW: So how does it know where you are?

AMY MYRBO: Uses your GPS, which is completely legitimate in airplane mode. We get that question a lot.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So what are the easiest things to spot when you want to try this out first?

AMY MYRBO: I would say the easiest things to spot are man-made features, right? We see centerpoint irrigation, and crop land, and dams, and you can see what cities you’re flying over. There are of course geologically a lot of fantastic things, like volcanoes, and glaciers, and mountain ranges, and huge rivers, but there’s some maybe more subtle things that I think the app can tell you about.

I of course fly into– I live in Minneapolis and fly in and out of there a lot. And I love thinking about when I get close to home, and see all of those lakes and rivers, and how 15,000 years ago, there was probably a half-mile thick sheet of ice on top of the region, and that’s why all those lakes and rivers are here. As the ice melted back, it left blocks of ice, and gravel, and dirt and garbage. And those finally melted out, and those are the thousands of lakes in the Upper Midwest in the Great Lakes region. There are many other things.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Yeah, well one of those things that I love flying over are mountains, and trying to figure out first, which mountains I’m flying over. And second, how the mountains were made. Does the app tell you anything about the geological history?

AMY MYRBO: It does. So the databases that we’re currently calling are one that gives you a geologic map that for each of the rock units, it tells you a little bit about it. That’s from a resource in Madison University of Wisconsin called Macrostrat. It goes out to a couple of fossil databases. But our biggest source of information right now is actually Wikipedia. There are a huge amount of articles about physiographic features and geologic features on all over the world really, because the app works worldwide. It’s not just US or North America.

And those articles are of course of varying quality, but they tend to be pretty good. And they tell you, and they reference scientific literature, and tell you a lot about the history, and formation and connections between that geology and somewhere else.

IRA FLATOW: Will it tell you all about the different river types that you’re flying over?

AMY MYRBO: Yeah, absolutely. We have a feature in there called “What is That?” that we sort of absorbed from a researcher at Bryn Mawr, Selby Hearth. And she did a lot of stuff with Google Maps images and sort of the basic geology geomorphology of land form– so different kinds of rivers, different formations of lakes, valleys, and volcanoes, and mountains, and rifts, and human-made features, and things like that. So it’s all sorts of cool stuff to entertain yourself with, as well as the things you’re flying over.

IRA FLATOW: And some of the most interesting things are when you see the terrain change from a mountain to a flat area, and you wonder, how did that happen?

AMY MYRBO: Yeah, flying into Denver is one of the greatest examples of that. Or I flew into Albuquerque last week, and it was flat, flat, flat, flat, flat. And then boom, there are mountains, and it gets pretty exciting.

IRA FLATOW: You know what you should– I’m not going to tell you what to do, but I [INAUDIBLE]. Get it on the back seats of the– get the app loaded into the video viewers that are already on the planes.

AMY MYRBO: We would love that. And you may see that in your future.

IRA FLATOW: That would be ultra cool. Can you find remnants of old lakes and things like that that used to be there?

AMY MYRBO: Yeah. That’s one of the things that I think is cool flying across the sort of the Great Lakes region in the Upper Midwest. A lot of that landscape has been drained for agriculture over the last 100, 150 years. And but especially when before and after the crops are on– so sort of spring, fall, winter, if you don’t have a whole lot of snow, you can see a lot of patterning in the grounds. It’s still there. The soil is different where there used to be a lake or a river. And there’s a little bit of topography, but you can mostly see it in the colors and textures of the ground, and sort of think back.

I’m a paleo scientist. I study cores from lakes. And so, I love thinking about that long-term history of the landscape, and really how human impacts have overprinted and interacted with that over more recent times.

IRA FLATOW: Let me see if I can get a phone call in. Let’s go to Salt Lake. Keenan, hi welcome to “Science Friday.”

KEENAN: Yeah, I’m wondering. So when I’m at altitude in an airplane, I’m looking down, and I’m always seeing cloud cover. So I’m wondering– OK, so I could just be super unlucky, but it seems like once you go to that high an altitude, you are seeing mainly just the high altitude cloud coverage. So how do you figure out exactly a flight that’s going to be at a low enough altitude. Or are flight over Oregon always going to just show nothing because of the rain?

AMY MYRBO: You may be flying on those rainy days. No, it is true that that’s a bummer. Sometimes, we fly over the west. It’s cloudy all the way. And sometimes, you get lucky. You can use in Flyover Country, you can look at a satellite map, so you can see as if you were using Google Earth, see what’s underneath those clouds. But, you could also just enjoy the wonder of the clouds.

We actually have a local Minneapolis Saint Paul climatologist and weather enthusiast who is working with us to write a description of what you can learn about clouds, different types of clouds, and what they say about weather patterns and the landscape below, and why you shouldn’t be freaked out by turbulence.

IRA FLATOW: There you go. What about the man-made objects, like I mentioned wind farms? But there are all kinds of things like mines, and farms and stuff like that.

AMY MYRBO: Yeah, golf courses are pretty easy to see.

IRA FLATOW: Especially in Minnesota, right?

AMY MYRBO: Especially in Minnesota.

[COUGHS]

Excuse me. There are oil patches, dams. So in lots of parts of the country that aren’t as lucky as we are in Minnesota to have tons and tons of lakes, the only lakes are made by damming rivers. And those have a really specific shape– sort of flat at one end where the dam is. And those are kind of cool to spot.

IRA FLATOW: And if you look on the coast where the oceans are, I mean–

AMY MYRBO: Oh my gosh, there’s such beautiful coastal geomorphology. And it changes so quickly, right? Humans are really trying, have to fight a really uphill battle to try to keep the coast, keep towns, and homes, and roads, and things where they are close to the coast, because it’s such a dynamic environment.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Ann Myrbo, thank you. Amy Myrbo, thank you for taking time. I can’t wait to get up on my next flight and try out the app. It’s called Flyover Country.

AMY MYRBO: And it is funded by the National Science Foundation. I would like to emphasize that. They have been wonderful and enthusiastic.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Amy is a researcher in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. Thank you doctor, for joining us today.

AMY MYRBO: Thanks so much, Ira.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.