Does Math Have A Place In The Courtroom?

17:08 minutes

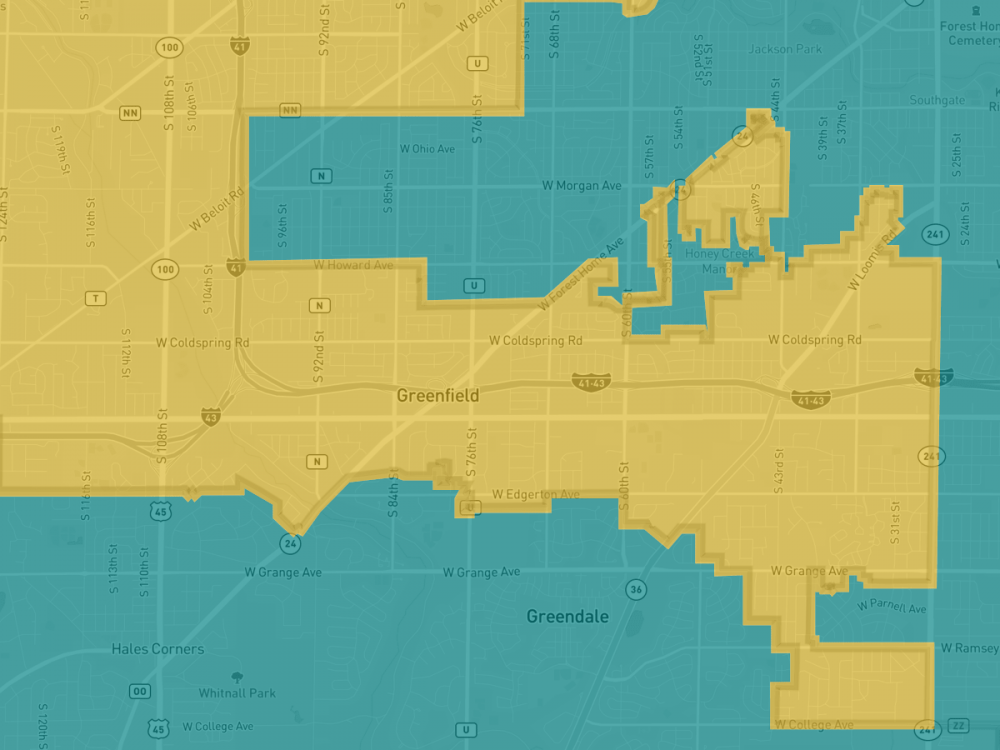

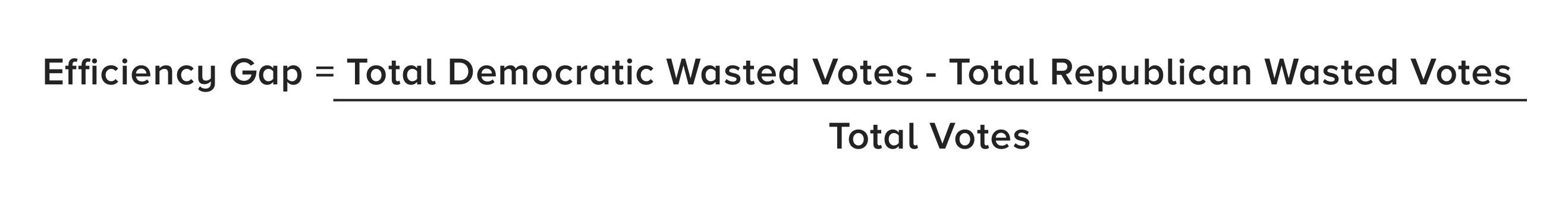

Last month the Supreme Court justices heard oral arguments for a case concerning gerrymandering in the state of Wisconsin. The democratic plaintiffs proposed a simple metric for determining whether the boundaries of a district had been fairly drawn. It’s called the “efficiency gap.” To calculate it, you take the difference between each party’s “wasted” votes—votes for losing candidates and votes for winning candidates beyond what the candidate needed to win—and divide that by the total number of votes cast. Simple arithmetic.

Not according to the justices. Justice John Roberts called the formula “sociological gobbledygook.” Justice Neil Gorsuch compared the metric to his steak rub recipe: “I like some turmeric, I like a few other little ingredients, but I’m not going to tell you how much of each. And so what’s this court supposed to do? A pinch of this, a pinch of that?” Even Justice Breyer, who is expected to vote with the court’s liberal bloc, generalized the details of the plaintiffs argument as all that “computer stuff.”

[Hedy Lamarr was so much more than a pretty face.]

So is it possible that these Ivy League-educated Supreme Court justices really don’t understand the math of this case? Oliver Roeder, senior writer for FiveThirtyEight joins Ira to discuss whether the Supreme Court is allergic to math, and what that means for future cases. And Moon Duchin, associate professor of mathematics at Tufts University, returns to discuss the best math to use for rooting out gerrymandering.

Oliver Roeder is a senior writer at Fivethirtyeight. He’s based in Brooklyn, New York.

Moon Duchin is an associate professor of Mathematics at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Last month, the Supreme Court justices heard oral arguments for a case concerning gerrymandering in the state of Wisconsin. The democratic plaintiffs proposed a simple mathematical formula for determining whether the boundaries of a district had been fairly drawn. It’s this simple– you take two numbers, subtract them, and then divide by the whole. Simple arithmetic, right? Well, not according to the justices. They used words like “baloney” and “gobbledygook” to describe the formula. At one point, Justice Breyer referred to the plaintiff’s arguments as, quote, “all that computer stuff.”

So is it possible that the Supreme Court justices, ivy-league educated, sitting on the highest court in the US, really don’t understand the simple arithmetic in this case? Joining me are two guests who are going to help us get to the bottom of this gobbledygook– Oliver Roeder is senior writer for Five Thirty Eight. Welcome to Science Friday.

OLIVER ROEDER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And back again with us to talk about gerrymandering math is Moon Duchin, associate professor of mathematics at Tufts University. Welcome back, Moon.

MOON DUCHIN: Thanks

IRA FLATOW: Oliver, can you quickly describe for us the math in this case? I know you can, because it’s very simple.

OLIVER ROEDER: Sure. So it’s called the efficiency gap, and it’s meant to get at this idea of wasted votes. So you take a party’s total wasted votes– so, wasted in the sense of votes for a losing candidate or votes for a winning candidate beyond what he or she needed– and you divide that by the total number of votes cast. And a gerrymanderer tries to get one party, essentially, to waste as many votes as it can. And that’s what the efficiency gap tries to get at.

IRA FLATOW: So what happened when the Supreme Court justices heard arguments in this case, when they were presented with this simple–

OLIVER ROEDER: A few of them, as I wrote in my piece at Five Thirty Eight, seemed to be allergic to taking this kind of math seriously. You mentioned that Chief Justice John Roberts described it as “sociological gobbledygook.” Never mind that this is a man with two degrees from Harvard and this case has very little to do with sociology. And we actually, we crunched a lot of numbers at Five Thirty Eight, and we looked it up, and this was only the fifth mention of the word “gobbledygook” we could find in the hundreds of years’ history of the Supreme Court.

But even across the aisle, you mentioned Breyer– solid liberal, sort of expressing some disdain for these social scientists and these computer experts. And you had the relatively new Justice, Gorsuch, comparing it to a secret recipe, his steak rub– a little bit of this, a little bit of that. So kind of across the board, a lot of– I don’t think disdain is too strong of a word. Kind of–

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Wow. Now, Moon, was the efficiency gap, do you think, clearly explained enough that the judges should be able to understand the simple arithmetic?

MOON DUCHIN: Well, I have a little bit of a different view of what was going on, because what happened here– we were listening to oral arguments at the Supreme Court level, but the case started out in a district court, then it went to a circuit court and the Supreme Court. And at every higher level, the plaintiffs– the ones challenging the map in Wisconsin– broadened the scope a little bit of which metrics they wanted to consider. So it’s true that at first, they really relied on efficiency gap.

But by the time it had made it up to the Supreme Court, they had widened the scope quite a bit to considering other metrics as well. And I think that’s part of what we actually heard the justices grumbling about. It’s what Misha Tseytlin, who is the Solicitor General of Wisconsin, was sort of defending– Wisconsin’s map. He called it a “social science hodgepodge,” and Roberts was just upping the ante on that by going from “social science hodgepodge” to “sociological gobbledygook.” So I think part of the complaint was actually that it wasn’t just efficiency gap, there were a proliferation of different kinds of methods.

IRA FLATOW: Oliver, [? do you want to ?] react to that?

OLIVER ROEDER: No, I think that’s totally, totally right. But I think there’s sort of a two-pronged issue, in my opinion, with what we heard at the oral argument. I think one is an unwillingness for just some of the justices to take math and empirical social science seriously, regardless of the specific form in which it’s presented at the court. And I think that that problem is going to be exacerbated in a computer and, quote unquote, “big data age.”

I mean, you can easily imagine a case that the court might hear in the next few years about, say, algorithmic bias, or something where you can only sort of understand and uncover an unconstitutional bias using relatively sophisticated, say, econometric methods or statistical methods. I think that’s one problem. I think the other concern is that the disdain expressed by some of the justices is a smokescreen, is not a kind of genuinely held objection, but rather is masking some other ideological objection that they might have– in this case, to thinking that gerrymandering is not unconstitutional, and sort of hiding an ideological objection behind feigned inability to do the math.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re basically saying these judges should have been able to understand simple math that you just described?

OLIVER ROEDER: Well, I mean, they’re smart. They’re smart people. Right?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. And they have people who work for them whom might be able to explain them, if they couldn’t. Moon, you’ve said–

MOON DUCHIN: Well, right, and–

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

MOON DUCHIN: Oh, I wanted to say, along those lines exactly, Roberts makes a really interesting move in the oral arguments where he says, oh, it’s not me. It’s not that I don’t understand this. But what about the poor intelligent man on the street? Let’s worry about him. Whatever will he think? And when Roberts is wringing his hands a little bit about the man on the street, he does his best to make this kind of simple addition sound kind of mystifying. You know, the signature of that is when, instead of saying, “add something up,” he says, “take the sigma.” And that is just trying to make addition sound scary, and that’s something that we should note.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. [LAUGHTER] That’s why they’re justices. We’re looking for justice. Moon, what do you think– is some of this confusion– I understand you have a better method that you would like to advance than this formula?

MOON DUCHIN: Oh, actually, it’s not so much that– it’s an emerging consensus, I think, that we heard about over and over again in these very oral arguments that says that the state of the art is going to be an outlier analysis. So I wanted to say a couple words about that, but also to note that it’s already in the lexicon of these justices. There’s even an amusing piece in the oral arguments where Kagan is basically begging the attorneys to use the phrase “outlier analysis.” Don’t you want to say “outlier analysis?”

So what is this outlier analysis that might give us a breakthrough here? Well, it says if you want to understand whether a particular map is too abusive– and that’s the thing the justices are worried about here, is a manageable standard for how do you know when something goes too far? And so this approach says, let’s use computers to help us get out of this mess. Let’s try to understand the giant space of all the possible plans, all the possible districting plans.

What if you knew something about those many millions of maps, and you could sample from that space, just the plans that are legally valid– that meet all the criteria that a plan has to meet? If you can look at all those along any attribute– you could look at them by efficiency gap, simply by the number of seats for the Democrats or Republicans, by other partisan symmetry metrics, your favorite metric– what they’ll do is they’ll give you a bell curve. And a really easy intuitive test of whether a legislature’s proposed map sits in the meaty part of the bell curve, or does it sit way out in the tail? And I think that’s something that the justices have indicated that they’re comfortable with, and that’s great news for adjudicating gerrymandering, because the science is really coming together around how to do this replicably.

IRA FLATOW: So that’s what the ones in the tails– those would be the outliers, by definition?

MOON DUCHIN: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: So–

MOON DUCHIN: Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: The judges have already heard the arguments, and they’re going to write their opinions. Can they use the outlier idea instead of the other idea that was put forward instead of the efficiency gap if they wanted to rule on something?

MOON DUCHIN: Yeah, that’s a great question. The question is, how narrowly are they bound to the arguments that were advanced by the attorneys in that case? And I think if you look back at some Supreme Court history, Kennedy’s shown some willingness to strike out on his own. And so we’re just going to have to see how far that takes us in this case.

IRA FLATOW: Oliver, is the court’s unwillingness to embrace a mathematical solution specific to this gerrymandering case, or is this a larger pattern? Have we seen this in other cases?

OLIVER ROEDER: We’ve definitely seen this before, and I’m certainly not the first to raise this issue. It’s filled pages in academic legal journals. There’s a very famous death penalty case where the defendant cited a lot of very sophisticated, published, statistical work showing that when victims of crimes were black, the perpetrator was much less likely to be charged with the death penalty than if the victims were white– some, four times more likely– and presented this evidence to the Supreme Court, and argued that his being sentenced to death violated his equal protection rights. And the court basically rejected this argument out of hand, and he lost the case. And it’s been called the worst decision since Dred Scott, and this was in 1986.

There’s a long list of judges ignoring or misinterpreting statistical evidence that’s certainly not limited just to the math behind gerrymandering.

IRA FLATOW: Moon, do you think the justices want a solution that’s not tied to a formula or some metric? That they’re just looking for something other than the efficiency gap, or what you’re suggesting? They’re not comfortable?

MOON DUCHIN: Well, I have to tell you, as someone who has now spent some time trying to understand the legal history around gerrymandering, I would say they don’t quite know what they want. And that’s part of the problem. Famously, efficiency gap is kind of reverse engineered to please Kennedy, based on his prior writings about that, because it has seemed in the past that the court is demanding just one score, just because they’re looking for a standard that can be managed by courts and not just by experts, right? The problem is that, just in terms of the information theory, gerrymandering is far too complicated to be captured in a single score, and it’ll be hard to find a meaningful threshold for where to cut off permissibility in that score. And I think that’s why this outlier approach really is such a breakthrough, because it doesn’t bind you to a particular metric. It just builds a huge ensemble of alternatives, and unless you score them according to a legislature’s stated standards.

So I think it’s legally responsive, it’s flexible, and the technology and the math are really coming together to make it fairly easy to reproduce.

IRA FLATOW: Are any states themselves already adopting this as a technique that you know of?

MOON DUCHIN: That’s a great question. Not yet, but it is my hope that, particularly with independent commissions, we’ll start to see the use of these big ensembles of alternatives to adopt maps, and not just to challenge them. I think that that’s really something we should be looking for in the next five, ten years.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. I’m Ira Flatow talking about math and the law with Oliver Roeder, a senior writer for Five Thirty Eight, and Moon Duchin, associate professor of mathematics at Tufts University.

You know, we’re [? going to ?] need math for everything soon. I mean, for example, robots– they’re taking over much of our lives. What do you think the Supreme Court’s going to say when you talk about how a robot is programmed? You have to understand algorithms, like you say. You have to understand the math that goes into it.

IRA FLATOW: Right. And even this term, the court’s hearing a big cell phone data privacy case. So yeah, this is everywhere. And I totally agree with what Moon said about the court needs to find a workable and relatively simple standard to apply to certain things. But I also think that, at some point, there might be the need for a sort of sea change in what the court, how the court sort of sees math. Because the world is a very complicated and increasingly complicated place, and not everything that it’s going to have to adjudicate is going to be able to be boiled down to a simple fraction. Like in this case, and even that fraction is something Roberts said might erode the very legitimacy of the institution. I mean, it’s very dramatic language that he used in the oral argument. So I think the world is very complicated, and it’s not going to become simpler any time soon.

IRA FLATOW: And Moon, big data is everything now, right? You have to be able to speak in terms of data.

MOON DUCHIN: Absolutely. I mean, the current crisis in gerrymandering really is brought on by much more sophisticated uses of data. And actually, one of the things that should be alarming is that, with all the access to data that we have, down to the household level sometimes, you can make a gerrymander that doesn’t look as bad as your grandparents’ gerrymander. It doesn’t have to look like a reptile with teeth and claws and wings anymore in order to produce, really, kind of skewed outcomes. So we absolutely have to catch up to this problem in robust, mathematical, and quantitative ways.

IRA FLATOW: There are judges who admit that they are not phobic, that they actually– there was an article about a judge who loves to write code, right? Judges, just because they’re lawyers, or on the court, it doesn’t mean that they don’t understand maps.

IRA FLATOW: Many of my loved ones are lawyers. I have nothing but respect. My mom is a judge.

MOON DUCHIN: Some of my best friends are lawyers.

IRA FLATOW: Your mom’s a judge?

OLIVER ROEDER: My mom is a judge. So I have nothing but respect for the potential of lawyers and judges to understand math. And when I was reporting my story for Five Thirty Eight, I talked to people about what potential solutions or improvements might be, and they kind of pointed in a few different directions. One was just education– legal education. I mean, way back in 1897, Oliver Wendell Holmes gives this very famous speech called “The Path of the Law,” where he says that the future of the legal thinkers, the man of statistics and the man of economics. And I don’t think we’ve come that far since Oliver Wendell Holmes gave that speech, but I think, more and more, economics, statistics, empirical analysis is creeping in to legal education. I think that’s a great first step as the world becomes more empirical, or at least we understand it more empirically. And, too, I think, each justice has a number of clerks, right, who help them through the legal thinking and the opinion writing? Why not have empirical clerks? Why not have some trusted advisers for the court for the justices to help them understand or parse or think through the empirical evidence, in addition to the purely legal arguments?

IRA FLATOW: I think we’re going to leave it there, because– unless Moon, you have something to add to that?

MOON DUCHIN: Well, I did want to add one thing to that, which is I think it’s easy to get alarmed when we see the justices seeming to be scared of math and statistics. But remember that it’s the trial court at which the facts are supposed to be decided, and we have federal rules of evidence. We have standards for experts. And the more that experts can appeal to scientific consensus, the more traction that does seem to get in court. So I think, actually, if you read between the lines in this case, some of what the conservative justices are complaining about is just the very newness of efficiency gap, and the idea that it hasn’t been around long enough to be vetted. So what we can do, as a scientific community, is also take the time to debate openly in peer-reviewed journals about the best ways to measure these things. Get more mathematicians in the conversation and come to a kind of consensus.

IRA FLATOW: We started a debate right here with Oliver Roeder and Moon Duchin. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

OLIVER ROEDER: Thank you.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.