Rio Redux: A Second Life for the City’s Olympic Architecture

9:48 minutes

Reduce, reuse, and recycle aren’t the first words you think of upon seeing the shiny, just-finished stadiums that form the backdrop for each Olympic Games. But after the crowds have gone, every host city is left to face the problem of its vast, emptied Olympic complexes.

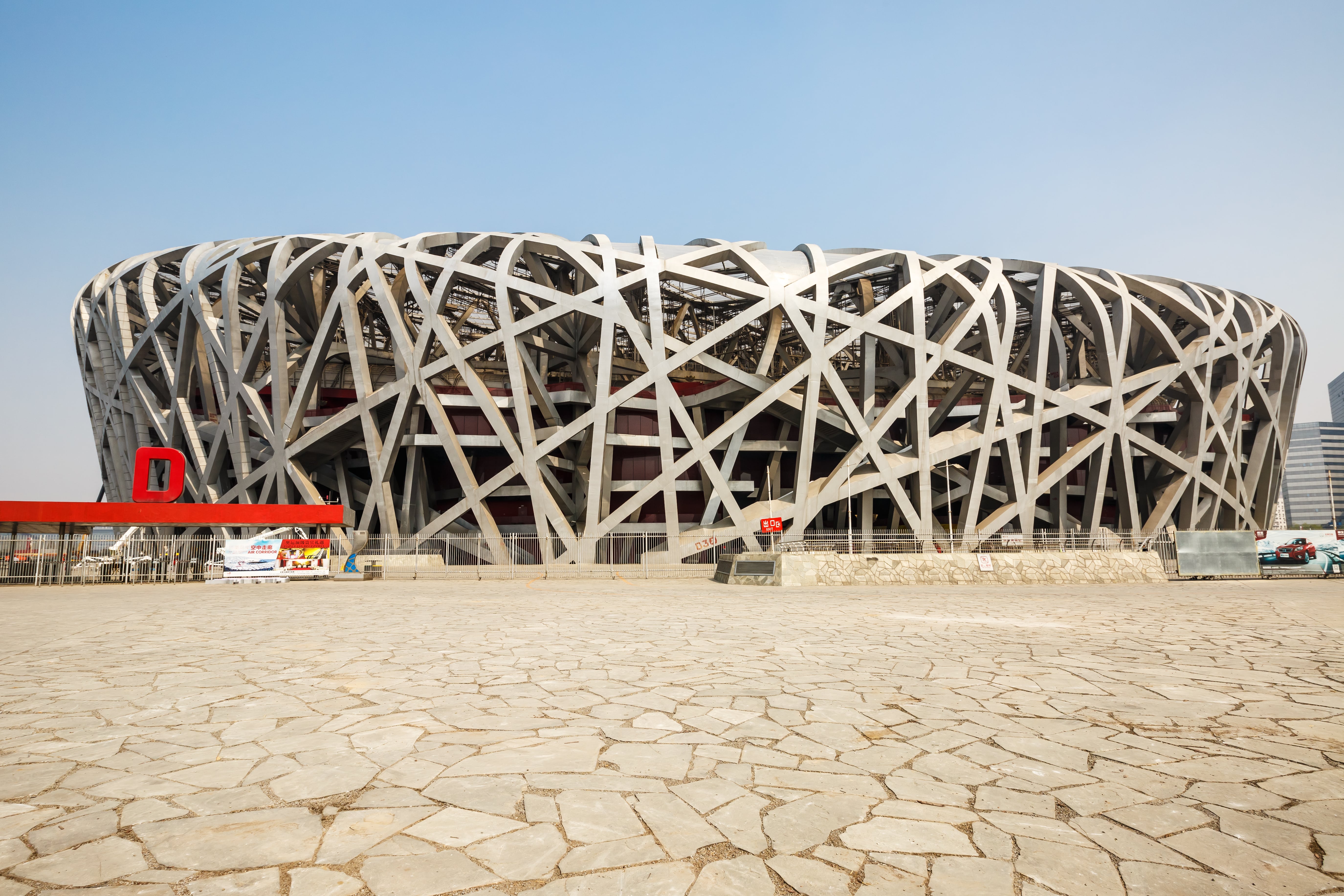

![Beijing National Stadium on August 16th, 2008 was heralded as an architectural marvel of the 2008 summer games. By Jmex60 (Own work) [GFDL or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.sciencefriday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Birdsnest1.jpg)

Do you need an 80,000-seat bird’s nest? (Asking for Beijing.)

Sam Lubell, a contributing writer for Wired and co-author of the forthcoming book “Never Built New York,” says that to reverse the trend of “white elephant” Olympic structures, the International Olympic Committee is encouraging host cities to think creatively about the next incarnations of their arenas and stadiums.

“Certainly Athens and Beijing are two of the poster children for empty Olympic parks,” Lubell says. “Rio is really focusing on a few stadiums that are not going to be that way at all.”

![The Olympics Aquatics Stadium in Rio De Janeiro will be broken down into two community swimming centers. By brasil2016.gov.br [CC BY 3.0 br], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.sciencefriday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Estádio_Aquático_Olímpico_2016.jpg)

In Rio de Janeiro, where billions of dollars have been spent on new Olympic infrastructure, including $38 million on a 20,000-seat aquatic stadium, organizers have planned second lives — and even second locations — for many of the buildings.

“They’re calling them ‘nomadic stadiums,’” Lubell says. “The idea is once you’re done with the games, you don’t just take the stadium apart and it’s done.”

Instead, organizers of the Rio Games will take the stadiums apart and use their components elsewhere, in some cases to serve entirely new purposes. The handball arena is slated to become four new city schools. That 20,000-seat aquatic stadium will be reborn as two community pools.

Looking beyond the Rio Games, similar (and even leaner) architectural recycling strategies are cropping up in plans for future Olympics. Last year Tokyo, which will host the 2020 Summer Olympics, scrapped Zaha Hadid’s design for a monumental helmet-shaped stadium in favor of a meeker option by Kengo Kuma. In addition to being much cheaper than Hadid’s plan, it’s hoped that Kuma’s new stadium design will blend in better with its surroundings. And Los Angeles, in its bid to host the 2024 Summer Olympics, is proposing mainly to retrofit and expand existing sports venues like the Coliseum, rather than build new ones.

And while Lubell says that such cost-saving and reuse plans aren’t required by the International Olympic Committee, they clearly improve a city’s bid — and can be evergreen public relations moves. Case in point? London, which hosted the 2012 Summer Games.

“London still is getting, for the most part, really good reviews for the way they handled the games,” Lubell says.

Lubell adds that not only did London repurpose, downsize, or deconstruct many of its stadiums after 2012, but the city also sited its arenas for maximum impact in the first place.

“London really used the Olympic Games to redevelop an area of theirs, which is the east side of London, that was historically underserved and… not in the best shape,” Lubell says. “That’s a plan that now is almost considered something mandatory.”

So the next time you scan Rio de Janeiro’s skyline for a visually arresting bird’s nest- or helmet-shaped stadium, look again. You may have to search until you see four schools, or two swimming pools, or a park.

“Architecture and urban design are becoming more and more of an enticement for the Olympics,” Lubell says. “And you know, look at the proposals — they’re getting so elaborate. They’re spending millions and millions of dollars on these renderings, and soon I’m sure it’s going to be a virtual reality fly-through, and you’re going to be able to see what the Games are like. And it’s a huge part of getting the games.”

Author and journalist Sam Lubell is the co-author of Never Built New York (Metropolis Books, 2016). He’s based in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: Right now in Rio they’re in the thick of the 2016 Games. But in just over a week, the excitement will be over, the crowds will have gone. All that will be left is billions of dollars’ worth of new infrastructure, including $38 million spent on a 20,000-seat Olympics aquatic stadium– a venue Rio couldn’t even come close to filling again. The white elephant is a problem that every host city faces, but one for which Rio has come up with a creative solution.

Joining me now to talk about it is Sam Lubell. He’s a contributing writer for “Wired.” Welcome to “Science Friday,” Sam.

SAM LUBELL: Thanks, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: This is always a problem with Olympic Villages or World’s Fairs. I know here in New York we still have buildings left over from the ’39 World’s Fair, right?

SAM LUBELL: That is definitely true. Any big event that challenges– of course you need to accommodate many, many people, but after that you’re not going to have those crowds anymore. So what do you do with those buildings after everybody leaves?

IRA FLATOW: And what does Rio have in store for its Olympic infrastructure after the Games?

SAM LUBELL: Well, Rio is following a trend that the International Olympic Committee sort of set a standard, or set an initiative to change this white elephant problem. Certainly Athens and Beijing are two of the poster children for empty Olympic parks that have sort of ghost-like buildings sitting there empty, or mostly empty.

So the idea– Rio is really focusing on a few stadiums that are not going to be that way at all. In fact, they’re calling them “nomadic stadiums.” And the idea is, once you’re done with the Games, you don’t just take the stadium apart and then it’s done. You take the stadium– which is something that London really initiated in the last Olympics– but in this case, with nomadic, you take it apart and then you build it somewhere else as something completely different.

So, for instance, the handball arena is going to become four schools scattered around Rio. And the aquatic center that you mentioned will become two community pools outside of the main Olympic area.

IRA FLATOW: So are they doing this in advance now? Or, you know, Tokyo is going to be the next Summer Olympics.

SAM LUBELL: Right.

IRA FLATOW: Is Tokyo thinking about this in advance of how they might use their buildings later?

SAM LUBELL: Yeah. It’s definitely– they call it the “legacy mode,” and it’s something that every Olympic Games are thinking about. And I think it seems like there’s now two major kind of strategies, I think, that are really making things a little bit more sustainable after the Games leave.

One is what we’re talking about here. You have these lightweight stadiums that can either be taken apart, or taken down from like 80,000 seats to 20,000 seats, because you’re not going to need 80,000 seats. Or nomadic, so these really lightweight, prefabricated structures.

And then you have what actually Los Angeles is proposing for the 2024 Games, which is basically the idea of not building anything at all– using stadiums that exist already. Some people say, well, that’s the greenest thing of all, is to not build anything at all. Repurpose.

And I think Tokyo is looking at probably a combination of that. They headed the Games in the mid-century already, and they have a pretty extensive list of stadiums that are there already. So they’re going to have a mixture there. But LA is really looking to almost build nothing.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So you just use the stuff you have. Couldn’t you expand it? I mean, do they have an 80,000–

SAM LUBELL: I mean, the Coliseum–

IRA FLATOW: Coliseum is big.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah. It’s hosted a couple of Olympics, but it needs to be retrofitted. First of all, it bakes in the sun, there’s no shade, so they’re already building shade structures there– actually because the Rams will part-time be there until they get their own stadium, moving to LA.

But yeah, they can retrofit and change stadiums around. But it’s still more sustainable than building something from scratch.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Our number, 844-724-8255, if you’d like to talk about the Olympics and what happens to the buildings there.

Does the IOC– the International Olympic Committee– now require you, if you become a home city, that you come up with a plan for recycling your buildings?

SAM LUBELL: Well, it’s not– in my research, I couldn’t tell that it’s absolutely required. But they’ve made it very clear in their documents to potential cities that it’s something they’re looking for. So basically, if you want, like if you’re applying to become a host city now, and if you know if you want to get it, you’re basically going to need to do one of these strategies to get the Games.

IRA FLATOW: And it makes sense, because for example, Brazil– when Rio originally planned for their Games, Brazil was actually in great financial shape, right?

SAM LUBELL: A little different, yes.

IRA FLATOW: A little different than it is today, but now that they have buildings they can repurpose, that might be on the higher side than where they might have been if they hadn’t.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah. I think the idea of now that these stadiums– which again, an 80,000-seat, 50,000-seat arena just sitting there empty– it’s not going to help the community. But if you have these new schools that you’re building out of it, obviously that’s something that they’re going to need. So it makes a lot of sense. I think it’s a great idea.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk about how London or LA is compared to this. Let’s talk about London. London really thought this through–

SAM LUBELL: Oh, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: –when they started.

SAM LUBELL: Oh, London still is getting, for the most part, getting really good reviews for the way they handled the Games. And a lot of it was in response to previous Games which did not get quite as good reviews in the way they handled the legacy mode, as I’m saying. So quite a few of those stadiums in London were either able to be, as I said, taken down completely, or taken down from like 40,000 to 20,000.

The one big exception, actually, is the big Olympic Stadium, because the Olympic Stadium was supposed to be– I think it started at 80 and was supposed to go down to something like 20. But the economic downturn hit the entire world. And basically, they decided that once the Games, after they happened, they were actually now rented out to a soccer team and they never shrunk it. It’s still the full size, and they get the money from hosting giant soccer games there.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is “Science Friday” from PRI, Public Radio International. Talking with us, Sam Lubell, contributing writer for “Wired,” and co-author of the forthcoming book, “Never Built New York.” And I want to talk about your forthcoming book about never built, because you have studied a lot of architecture that I understand never got built in New York.

SAM LUBELL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Is there something to learn about never getting built in the Olympics that you learned from researching your book, and some lessons there?

SAM LUBELL: Well, it’s a good question. There is always a lot of lessons from things that were never built. I’m sort of now an expert in failure [INAUDIBLE].

IRA FLATOW: The Robert Moses– not– of New York City.

SAM LUBELL: Yes. And that’s a good lesson for– I mean, New York has tried to get the Olympics. The most recent one was– actually, I think they actually put together a pretty good scheme when they recently were trying for the Olympics. But they were real interested in repurposing– in doing what London did later.

I think London, this is a phenomenon that “Never Built” shows a lot, is people take– I don’t know if they actually took it one-to-one, but it gets into the water. This idea that for the New York Olympics, they wanted to build the Olympic Village to really redevelop Queens, near the waterfront.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, where the World’s Fair used to be.

SAM LUBELL: Or there was parts of it was by the World’s Fair. The Olympic Village was going to be basically right near the waterfront, near that no man’s land, where you get when you take the train over the water.

IRA FLATOW: Near Citi Field–

SAM LUBELL: Yeah, yeah. And they were going to really make an effort to– with the Olympic Village, they were going to make it into housing afterwards. They were going to make it– the ability to repurpose it after the Games was really a big part of that plan.

They didn’t win it, but then London really used the Olympic Games to redevelop an area of theirs, which is the east side of London, that was historically underserved and not in the best shape. And that’s a plan that now is almost considered something mandatory.

IRA FLATOW: Do you win points with the Olympic Committee if you have a forward-looking plan like that?

SAM LUBELL: Definitely.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah?

SAM LUBELL: Yeah. The Olympic Committee is looking for that. And as somebody that covers architecture, I see that architecture and urban design are becoming more and more of an enticement for the Olympics. And you look at the proposals, they’re getting so elaborate.

They’re spending millions and millions of dollars on these renderings. And soon, I’m sure it’s going to be virtual reality fly-throughs, and you’re going to be able to see what the Games are like. And it’s a huge part of getting the Games.

IRA FLATOW: As someone who covers architecture, how would you rate the Rio architecture compared to other Olympic attempts?

SAM LUBELL: I think that some of it is really interesting. I love this nomadic idea. I think it’s great. Some of those stadiums, they’re not architecturally– they’re not things that– Like the Bird’s Nest in Beijing that firm Herzog & de Meuron did was spectacular architecturally, but now it’s sitting empty, for the most part. There’s a few things. So it’s this hulking mass.

Whereas these are not quite as impressive architecturally, but they’re lightweight, they were prefabricated, they can be taken apart, they can be moved around, they’re much more flexible. So sometimes an aesthetic “wow” in the long term is not a great idea. And Rio does have some pretty “wow” stadiums. A lot of them are actually from the World Cup that they had a couple years ago, which they got a lot of flak for, for building a lot of new stadiums [INAUDIBLE]. So they sort of learned their lesson.

IRA FLATOW: They’ll have to resurrect the “Men in Black” facilities over at the World’s Fair site.

SAM LUBELL: Yeah. We’ll talk another time.

IRA FLATOW: You know those two towers I’m talking about.

SAM LUBELL: Yes. You’ll be surprised what they’ve proposed for there.

IRA FLATOW: We’re going to have you come back. But when is your book coming out?

SAM LUBELL: It’s in October. I’d love to.

IRA FLATOW: All right. We’ll have you come back. Sam Lubell, contributing writer for “Wired,” and co-author of the forthcoming book, “Never Built New York.” I can’t wait. I love talking about New York City architecture.

SAM LUBELL: I look forward to it. And thank you so much.

IRA FLATOW: Thanks for taking time to be with us.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.