Cassini’s Final Year, And Juno’s First

7:19 minutes

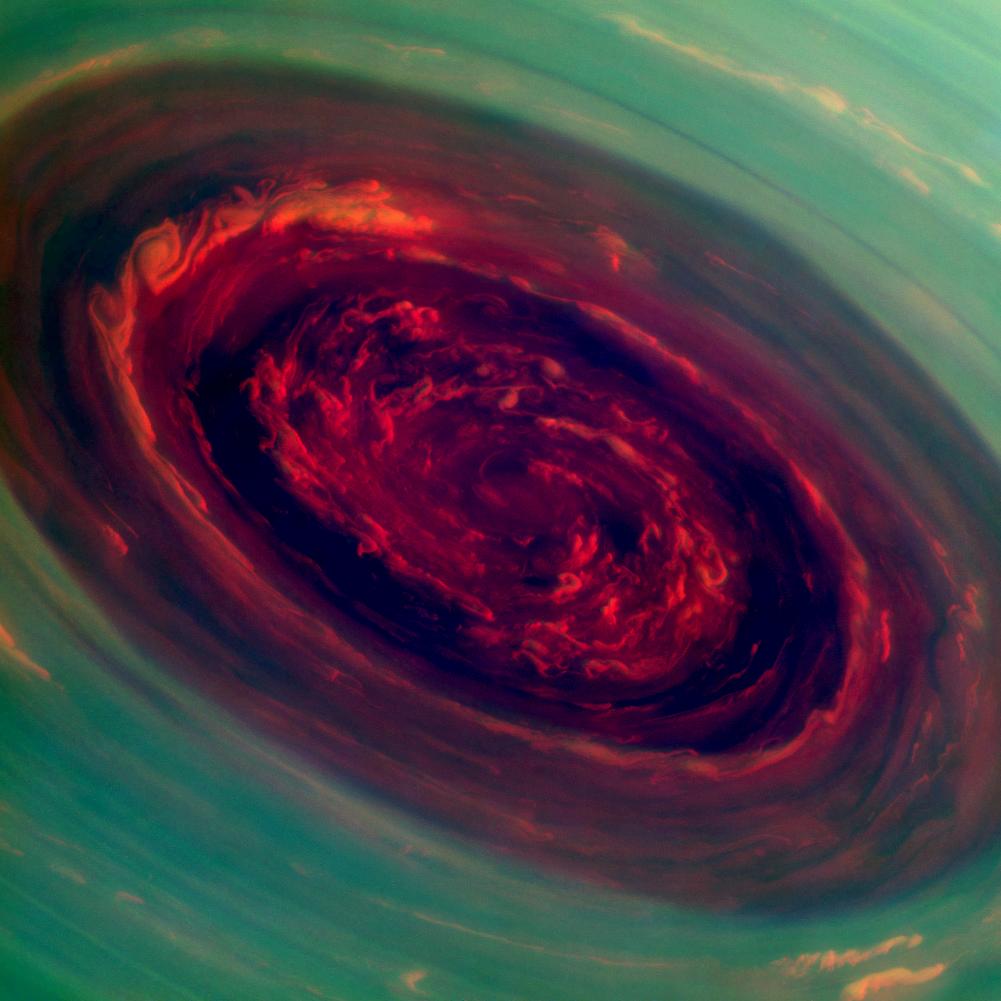

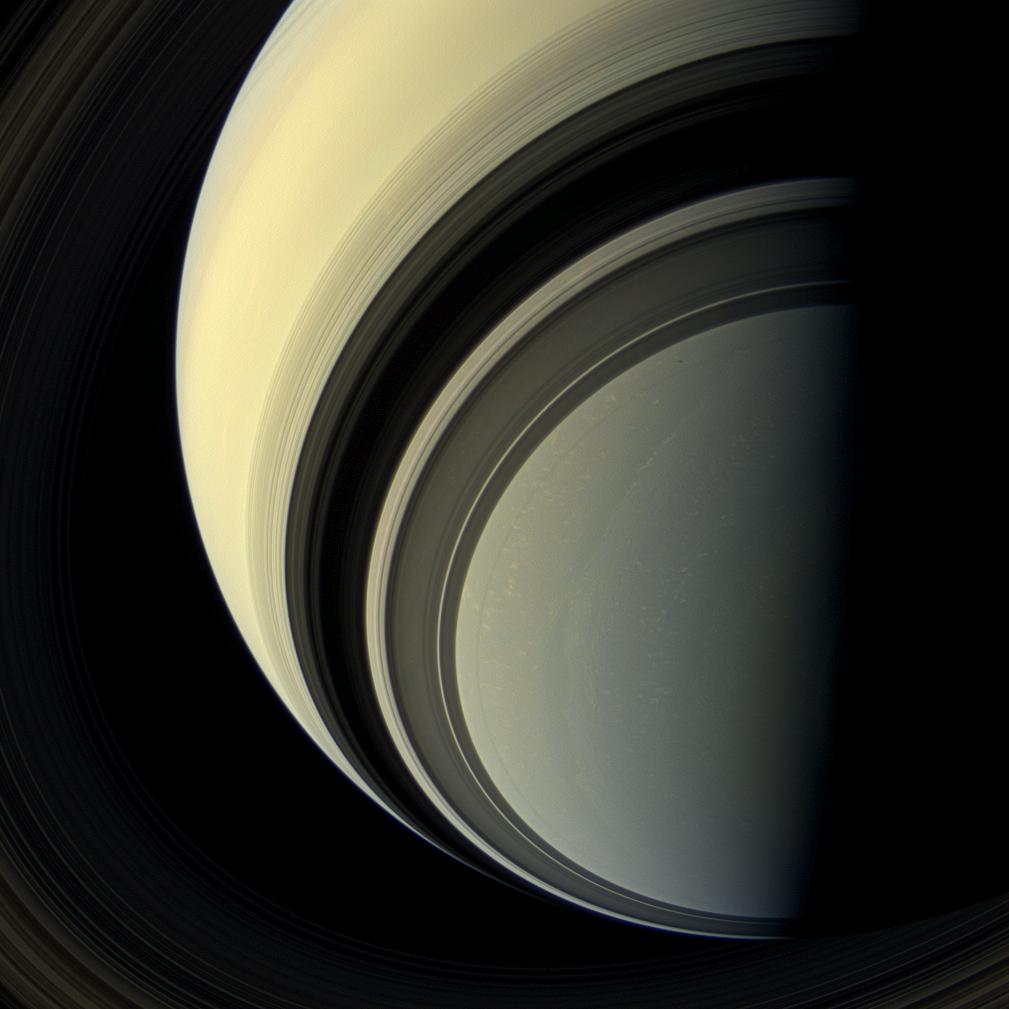

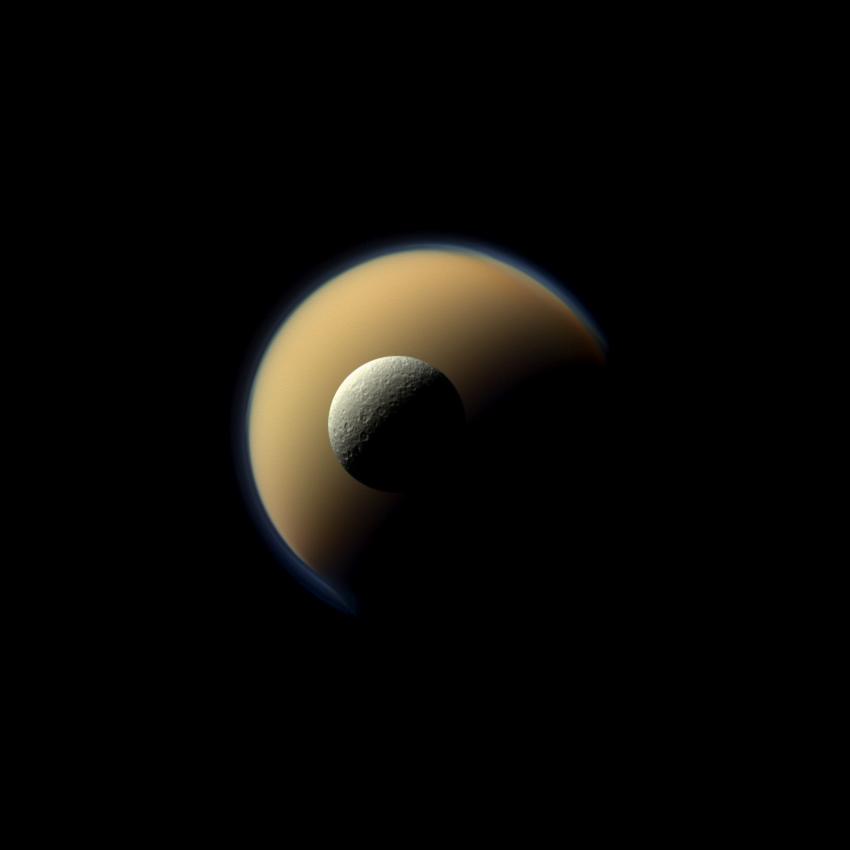

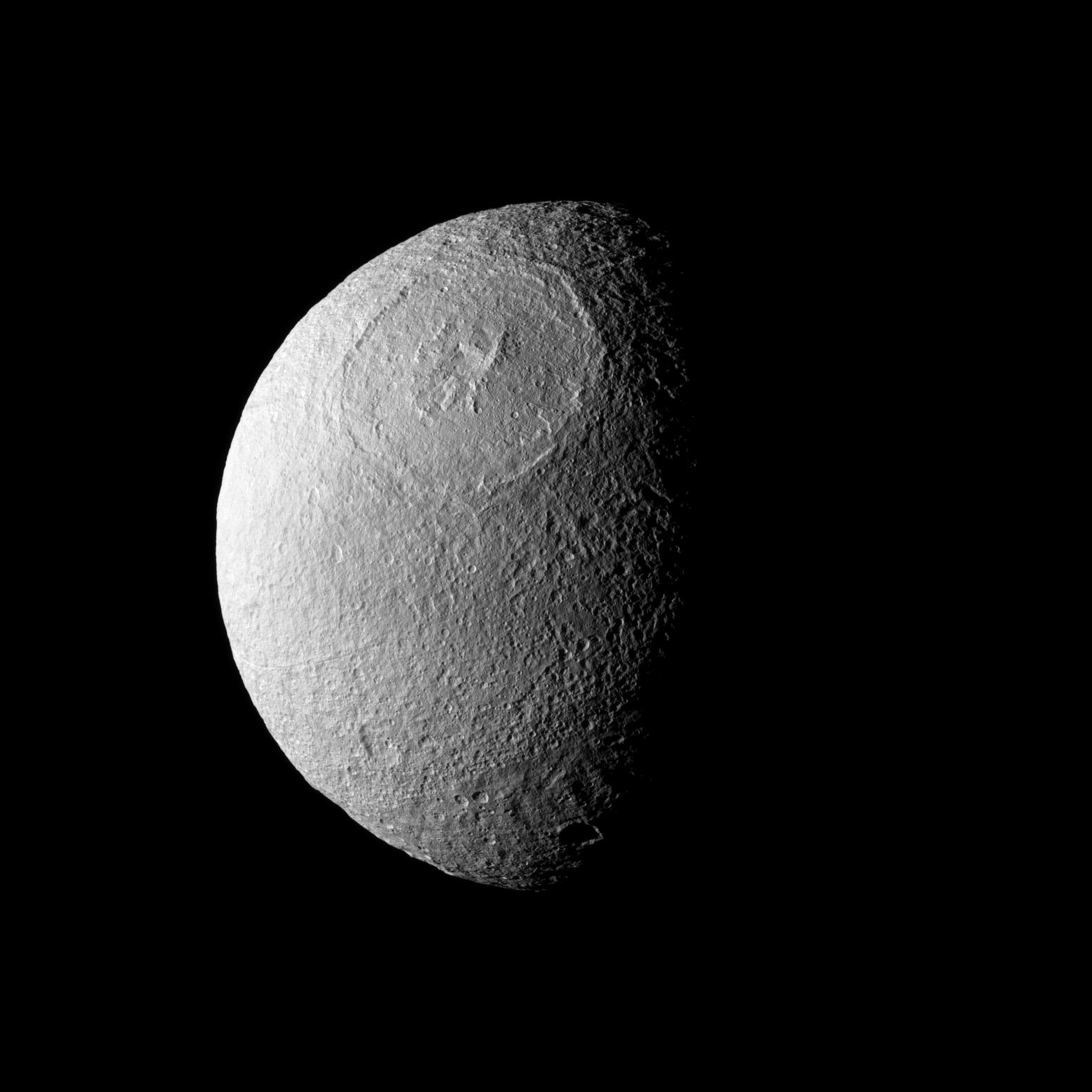

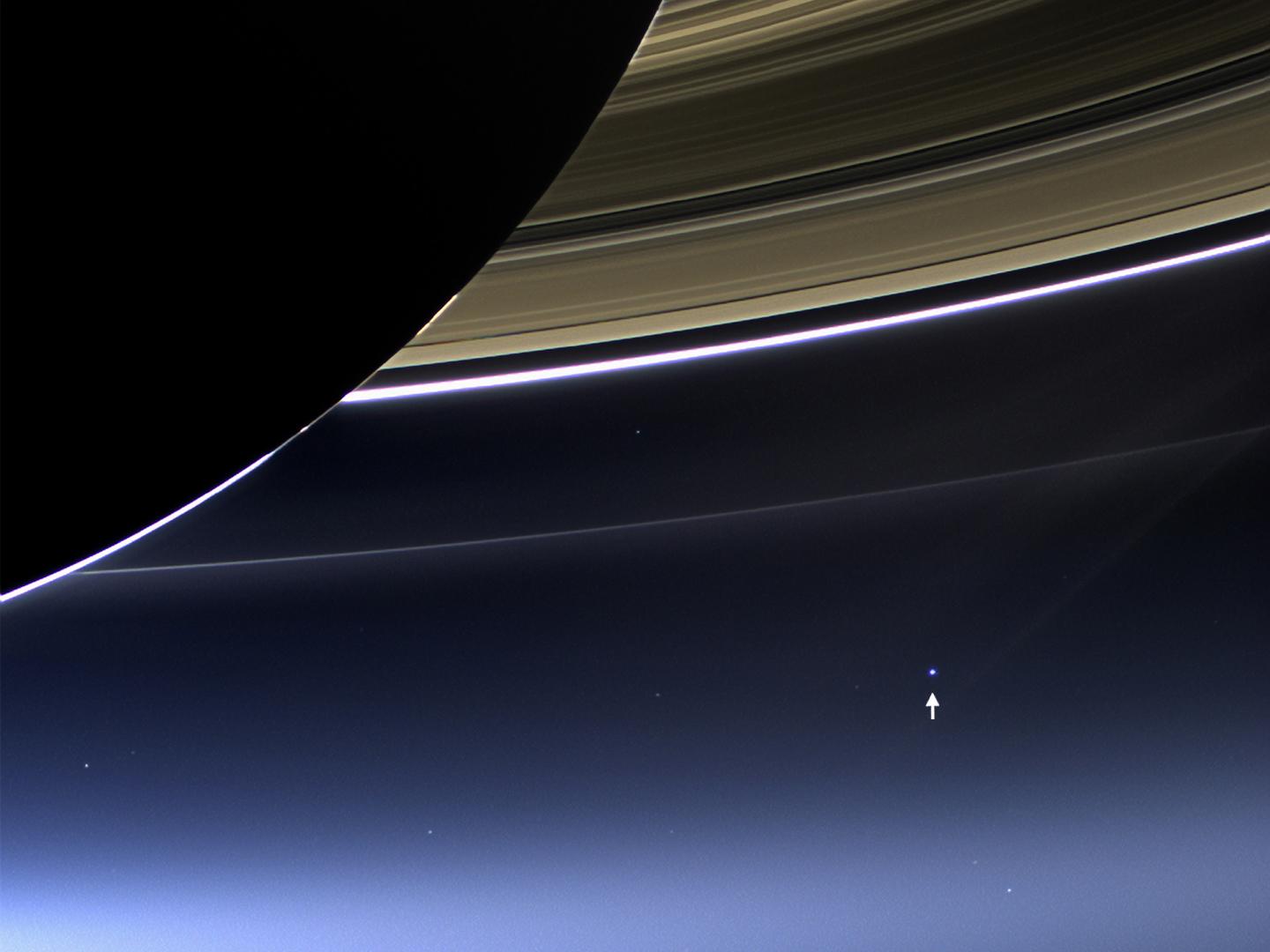

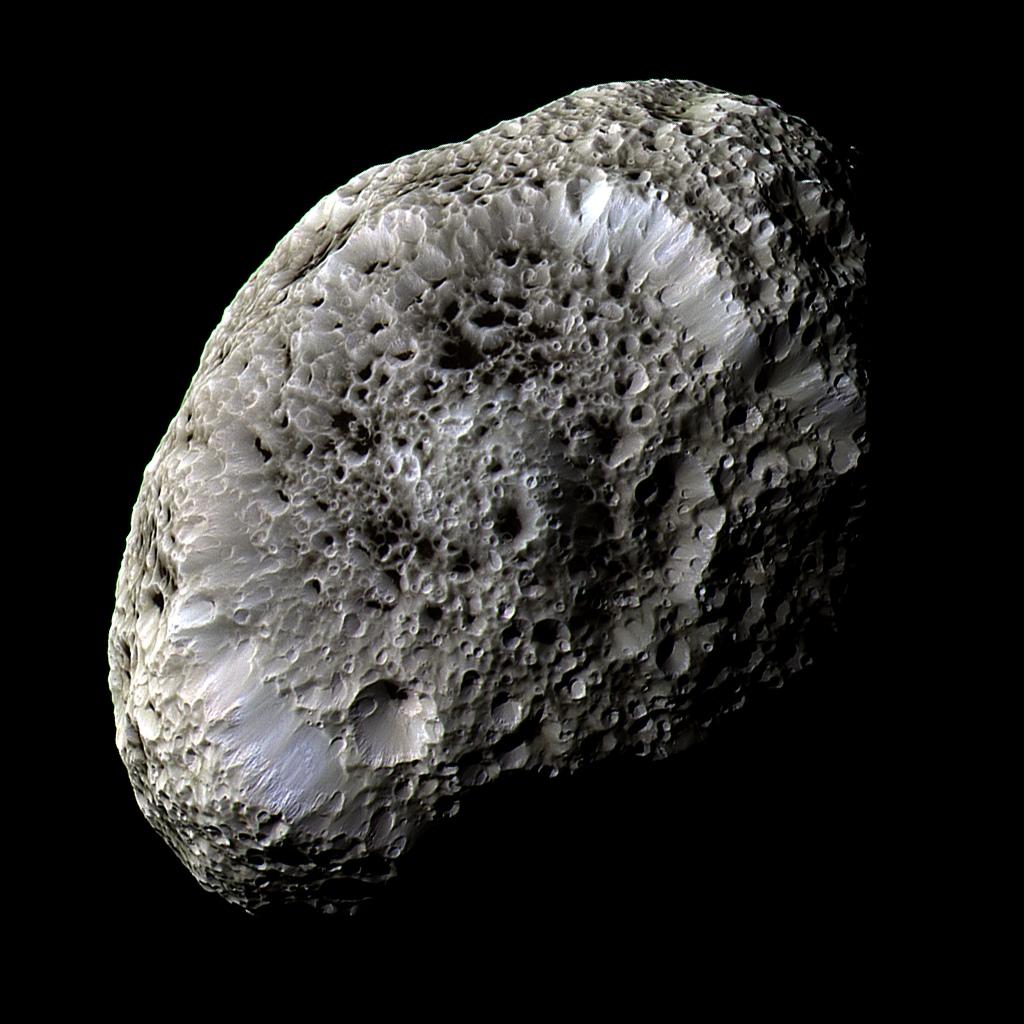

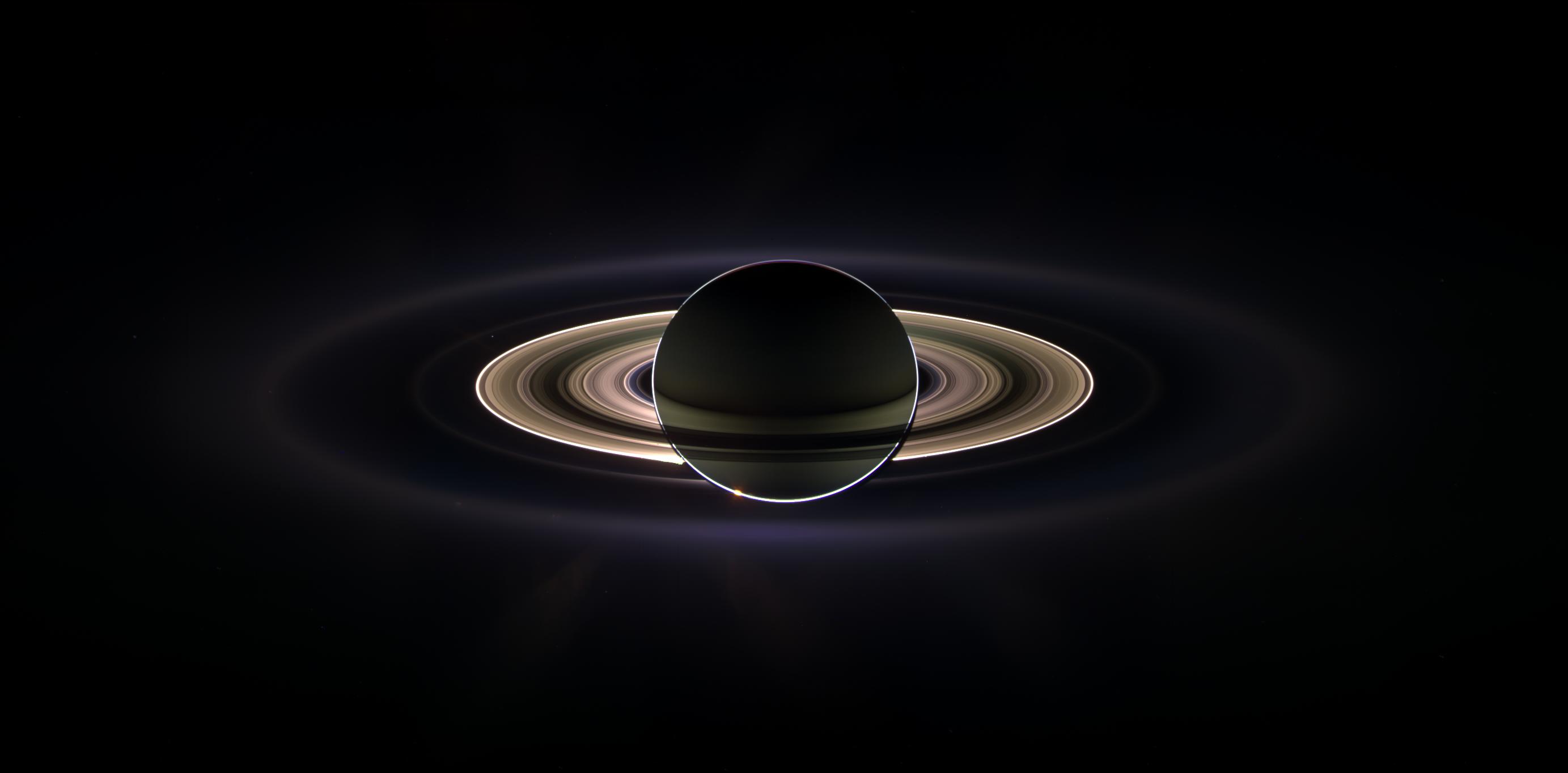

The Cassini mission to Saturn has brought us visions of the gas giant’s icy satellites, a new understanding of where life may be possible, and gorgeous photos of Saturn’s storm systems and rings. Now, running out of fuel, the orbiter will spend its last months getting its closest-ever look at the rings, then dive between them and the planet to “taste” the atmosphere.

[The next top candidate for life? Saturn’s moon, Enceladus.]

Meanwhile Juno, which arrived at Jupiter in July, has had some setbacks. It’s currently on a 53-day orbit of the planet, coming close enough to collect data only on the last day of each revolution. Plans to reroute Juno into a “science orbit”—which would enable the orbiter to capture data for 14 days in a row—have so far been delayed by technical problems. With another close approach to Jupiter (called “perijove”) occurring on December 11, Juno will once again collect data rather than shift into a new orbit.

NASA planetary sciences director James Green explains what’s next for these two outer solar system missions.

Listen to our 2004 segment when Cassini first arrived at Saturn.

We also gathered some of Cassini’s stunning photos throughout its mission.

James Green is the director of NASA’s Planetary Sciences Division in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: And now we explore the fate of Cassini and Juno, two different outer solar system missions, both trying to do big things this year. On Wednesday, Cassini began a new stage in its mission to Saturn. Over the next few months, the orbiter will get closer to Saturn’s rings than ever before.

And then it’s going a dive between the rings and the planet to sample the atmosphere, all culminating in September on a suicide mission, crashing into Saturn, and that will be the end of Cassini, which launched in 1997. We caught up this week with Cassini project scientist, Linda Spilker. She has been part of the team since the late 1980s.

DR. LINDA SPILKER: Cassini’s kind of gotten to be like a friend. We watch as she flies down the planet and getting ready to dive between the rings and Saturn. So there’s a little bit of that, like, sense of loss.

IRA FLATOW: And a much younger mission– the Juno orbiter arrived at Jupiter in July, and has already collected data that’s changing scientists’ understanding of its unique magnetosphere. But the mission has experienced some technical difficulties this fall. Juno is still in a long 53-day orbit rather than the intended 14-day science orbit that would allow more frequent data collection. Here to talk about what’s next for both missions is Dr. James Green, director of Planetary Sciences at NASA. Welcome to Science Friday.

DR. JAMES GREEN: Well, thanks so very much. It’s really exciting to be able to talk about these two fantastic missions.

IRA FLATOW: Before we go to you, here’s Dr. Spilker talking about the final plan for Cassini next September.

DR. LINDA SPILKER: We’re going to be continuously sending data back until the very last second when the atmosphere gets thick enough that it just turns our antenna away from the Earth. And it will be more like– imagine a giant, you know, like a meteor coming into the atmosphere of the Earth. We’re going to be at 75,000 miles an hour.

We’re going really, really fast. You know, the spacecraft will probably be torn apart. Those pieces will probably melt or vaporize and then the little bits of Cassini– these little bits that were sent from the earth will become part of Saturn. So down to the atom level basically.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Spilker talking about the final plan of her Cassini on Science Friday from Public Radio International. Not to forget that James Green– Dr. Green is here with us. He’s director of the Planetary Science at NASA. Dr. Green, are these sad times when the missions are over?

DR. JAMES GREEN: They are, but it’s really bittersweet for the simple reason both these missions are making so many observations that are so unique and important– things like understanding what the real mass of the rings are at Saturn and looking into the cloud structure and finding where the origin of its magnetic field is, while at the same time, Juno is doing that Jupiter– is looking deep into the planet, finding where the water layer is, and how much water the planet may have gathered at its early creation, which tells us where it might have actually accreted and started from. Because we now know these giant planets are in different locations today than when they were really created.

So these are just fantastic opportunities for us to learn really new things. But, indeed, at the end of Cassini’s last orbit, it will be very low on fuel– if not just vapors left– and so we’re going to ditch it. But we’ll learn a lot, all the way down as Linda says, into the depths of Saturn until it’s crushed and dissolved.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. I’m getting all misty just thinking about that. And Juno was supposed to enter in more science-friendly orbit last month, but it didn’t. What happened there?

DR. JAMES GREEN: Well, on its path, as we were getting ready– it had a what we now know is a software anomaly onboard, and this got it confused. And when that happens, it goes to a normal state and that is what we call a safe mode. And because it was in safe mode then, it went through the pass normal, but didn’t have any of the instruments on.

As it went back out away from Jupiter in its very long orbit, out to the apojove, which is at a great distance, it gave us time to really figure out what’s going on, find out how the software collided inside the spacecraft, and then create the patch, upload it, test it, and now we’re ready to go. Because on December 11th, we’re going to go shooting through the close passage again right over the tops of the clouds at perijove.

IRA FLATOW: What have we learned so far on this mission?

DR. JAMES GREEN: Oh, all kinds of things. You know, this is a new and unique view. And from the cameras, we see a completely different cloud structure than Cassini sees its Saturn in the northern and southern hemispheres.

We see far more cyclonic things at Jupiter, whereas at Saturn, we see this hexagon, this more of a regular structure in its jet stream, so to speak, in its upper atmosphere. We also observe the magnetic field at high resolution, so close to the planet that it tells us this planet Jupiter has a very complicated current system.

And, in fact, there may be several different types of currents that are arising inside it that create it’s very large and complicated magnetic field. In addition to that, we go right through the [INAUDIBLE] zone and we look at those particles that are precipitating coming down, being accelerated out of the magnetosphere, and hammering into the atmosphere, glowing that atmosphere so we can see the spectacular auroras. Gives us an idea of their temperature, their densities, the types– in terms of whether they’re electrons, protons, all the masses– and we really can tease out some of these processes that are occurring in the magnetospheres.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Green, thank you for taking time to be with us. We’ll be watching forward. Dr. James Green, director of NASA Planetary Science division. Couple of last things before we go– speaking of space, remember that weird star that was in the news earlier this year, the one with the spooky, potentially alien dips in brightness?

Researchers are now searching for signs of intelligent life coming from that star. It’s a long shot, but if they actually find something, what then? Read about it at sciencefriday.com/aliens.

Charles Bergquist is our director. Senior producer– Christopher Intagliata. Our producers are Alexa Lim, Annie Minoff, Christie Taylor, Katie Hiler, Luke Groskin, our video producer, Rich Kim, our technical director, [INAUDIBLE] Horowitz and Sarah Fishman, our engineers at the controls here at the studios of our production partners, The City University of New York. And that play I couldn’t remember before? Mark Mezadourian tweeted it’s Constellations. How could I forget that? I’m Ira Flatow in New York.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.