Chasing A Butterfly Down Its Changing Migration Route

Each year, painted lady butterflies migrate thousands of miles between Africa and Europe. As the environment changes, so do their journeys.

A painted lady butterfly waiting on a rocky hilltop for a mate. Credit: Lucas Foglia

To find a painted lady butterfly, you have to think like one. During the day, they look for blooming flowers. And at sunset, they gather on higher ground to mate.

Fine art photographer Lucas Foglia figured out how to find the butterflies with one question: “If I asked teenagers where they go on dates, then they would tell me about the high hilltop with a beautiful view of the sunset,” he says. “And that’s where you’d find the butterflies.”

Foglia figured this out while tagging along with Dr. Gerard Talavera, an entomologist at the Institut Botànic de Barcelona, from 2021 to 2023. He and some other scientists were collecting painted lady butterflies across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa to map how their long migration unfolds across the continents. At first, Foglia’s plan was to learn about and photograph these migratory butterflies while the world was opening up again in the wake of COVID-19. But soon, it became a project that showed how humans’ and the butterflies’ journeys felt intertwined.

These parallels between humans and painted lady butterflies come together in Foglia’s new photography book, Constant Bloom. It documents his travels over three years across 18 countries learning about painted lady butterflies, the people they encounter, and the researchers unraveling their mysteries.

Long before he was seeking out the best makeout spots in different countries, Foglia was captivated by the painted lady butterfly’s free-spirited movement.

Over the course of a year, and the span of up to ten generations, hundreds of thousands of painted ladies will cross from south of the Sahara desert in Africa into Northern Europe and back again. It’s a common butterfly species, with established populations in North America, Africa, Europe, and Asia, and they have distinct migrations in different parts of the world. But pinning down their exact migratory patterns beyond broad strokes remains difficult.

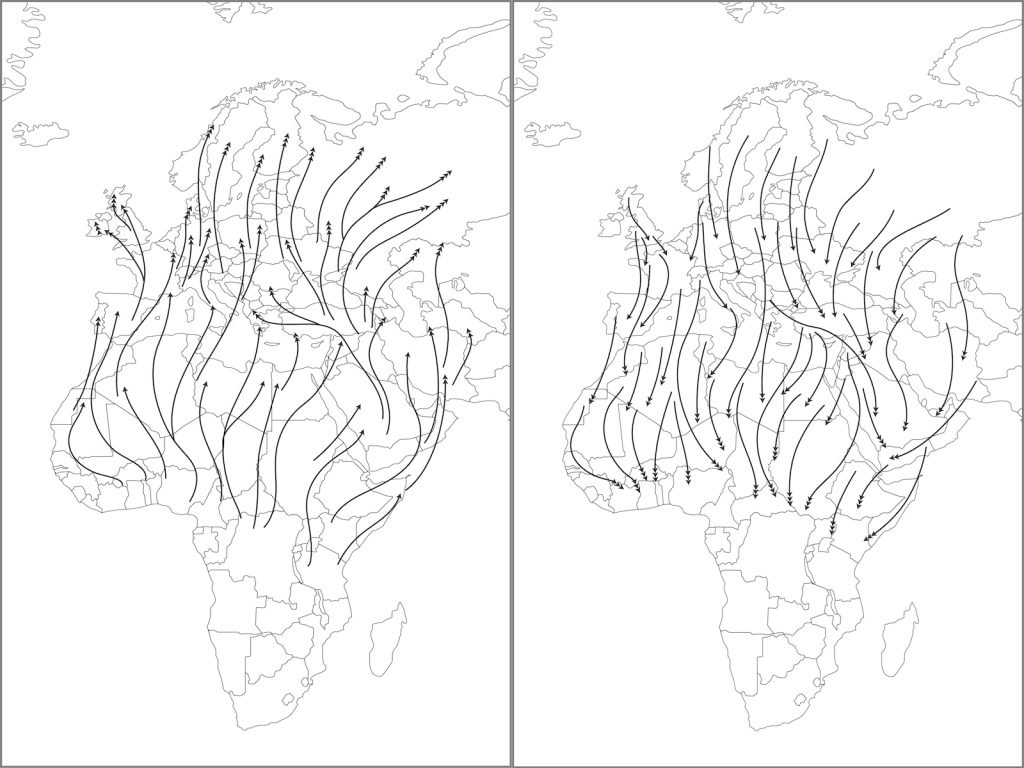

Our understanding of how painted ladies migrate between Africa and Europe could be compared to a pulsing heartbeat, Talavera says. Massive populations move north and south on a relatively predictable timeline, but knowing exactly where groups of them come from and end up every year is more complicated.

“People try to explain, ‘Oh, these butterflies from France are coming from Algeria.’ No. They are coming from Algeria, and from Spain, and from the Netherlands, and from [so on],” he says.

The butterflies aren’t driven to migrate to specific places like monarchs are, for example. Instead, they move as resources like food, suitable habitats, and host plants where they lay eggs become available. As the environment changes, painted lady butterflies change their course.

Climate factors, like temperature, rainfall, and winds, can dramatically change how many painted ladies migrate to Northern Europe in the summer. Talavera says that although he doesn’t know for sure how it will affect the butterflies, climate change is an “increasing source of pressure” for them. One possibility is that migration distances could be shortened or lengthened as seasonal changes vary along the route.

Foglia witnessed the butterflies finding homes in human-maintained gardens, farms, and parks when wild blooms failed due to climate change. “Painted lady butterflies and many other species are now depending on us when wildflowers are not blooming as they should,” he says.

Despite these challenges, painted ladies aren’t declining like many other species. They’re still thriving worldwide precisely because of their strong capacity to adapt—a quality that humans share, Foglia observed.

As the butterflies cross borders to get to more hospitable habitats, scientists must do the same to study their journeys. Whether it’s in the form of collaborating with scientists across borders or traveling there themselves, Talavera says it’s an essential part of the research. “Monitoring migratory butterflies cannot be done locally,” he says.

To expand his network of collaborators, in 2013, Talavera started the Worldwide Painted Lady Butterfly Migration Project, an international science effort between professional researchers and citizen scientists. While interested amateurs record their observations and collect butterfly data, professional members of the project have created detailed migration maps, explored the painted ladies’ genomes, and made connections between their genetics and their behavior.

In 2024, Talavera and his colleagues proved that a group of the butterflies had managed to cross the Atlantic Ocean. He has also proven that the painted lady migration across Africa and Europe occurs on a species-wide scale over multiple generations of butterflies. In the coming years, Talavera says he wants to use the monitoring systems he’s already spent a decade developing to understand more about the genetic underpinnings of this migration, see how their models can improve our understanding of other migratory animals, and raise awareness about the ecological importance of the phenomenon.

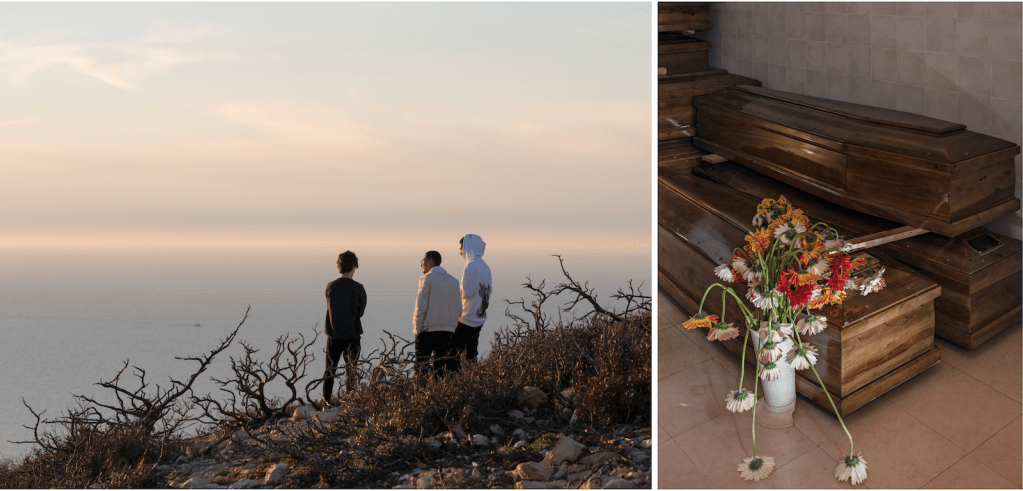

To Foglia, witnessing this insect’s migration recalls how humans also cross the same borders as they adapt to world events like war and climate change.

While he was photographing the butterflies making their way north from Tunisia, he met a teenager who was planning to make the same journey across the Mediterranean sea into Italy. As Foglia followed the butterflies north, they kept in touch.

“So many people I met were deciding whether to stay or to leave and cross what is now the deadliest human migration route in the world,” Foglia says. “At the same time … millions of painted lady butterflies were crossing the same sea.”

Emma Lee Gometz was Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. They wrote SciFri’s “Science Goes To The Movies” series and are a journalist and illustrator based in Queens, NY.