Tradition Meets TikTok At The Federal Duck Stamp Art Contest

A new group of social media-savvy wildlife artists is bringing a beloved conservation tradition to TikTok. It’s ruffled some feathers.

Artist Kira Sabin in their studio, painting a ruddy duck they named “Brimstone.” Credit: Greyley Sabin

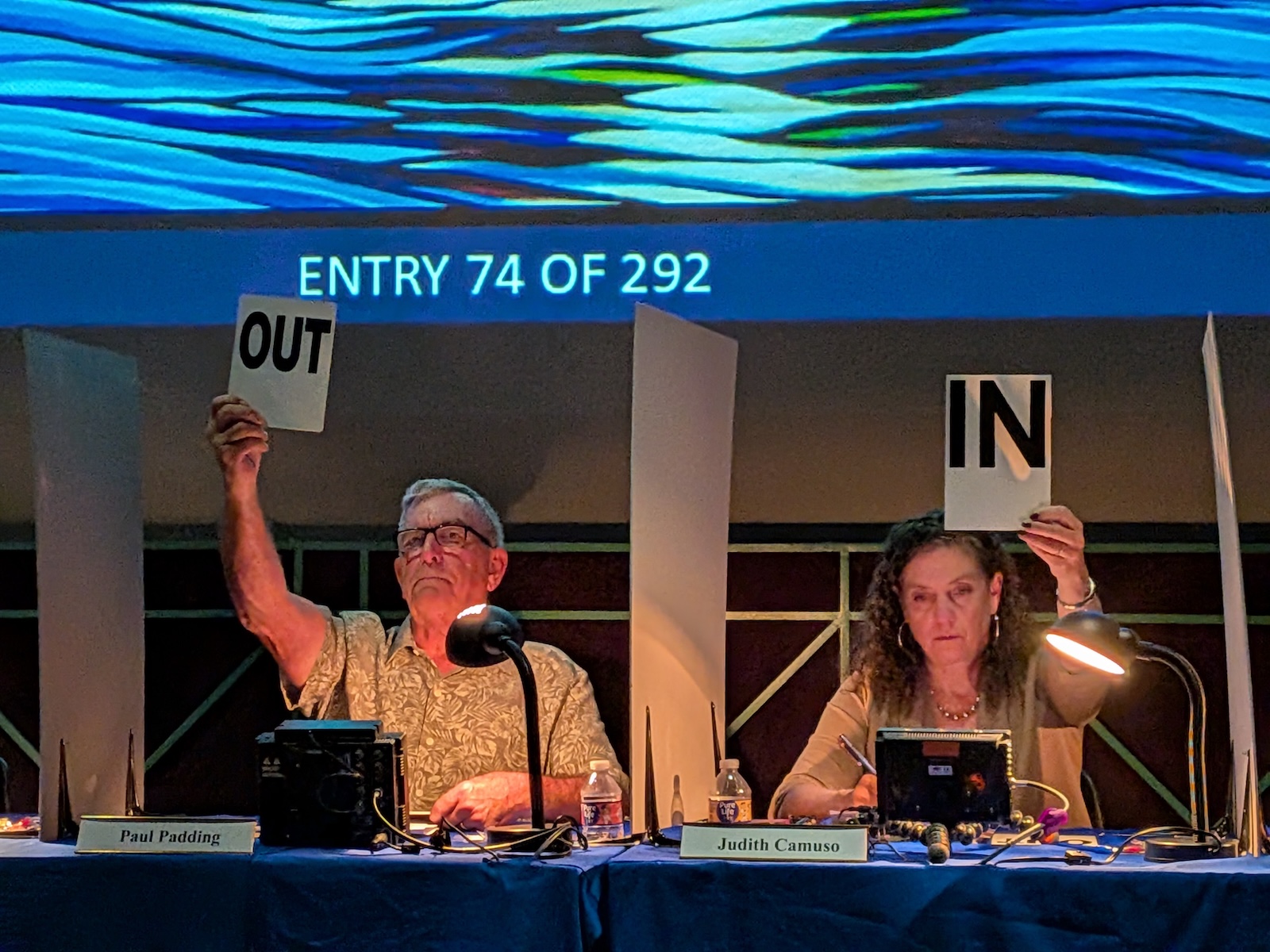

In a dark, silent auditorium in Laurel, Maryland, a painting labeled #122 is projected onto a screen. It shows a male wood duck with a striking green head floating serenely, while a grayish female sits on a log behind it. Five judges separated by partitions consider the painting, and after about 30 seconds all five raise a paddle with one word: OUT.

In a dark, silent auditorium in Laurel, Maryland, a painting labeled #122 is projected onto a screen. It shows a male wood duck with a striking green head floating serenely, while a grayish female sits on a log behind it. Five judges separated by partitions consider the painting, and after about 30 seconds all five raise a paddle with one word: OUT.

Hundreds of miles away, Liz Fuller, the artist who spent weeks painting entry number 122, is livestreaming the judging on Twitch to thousands of followers who had watched her paint the ducks from day one. Away from the stuffy arena of the judging, she falls back in her chair, laughing. The chat erupts with comments: “OMG I’m gonna pee myself,” “im crashing out,” “RUDE,” and “NOOOOOOOOOO” come streaming down the screen.

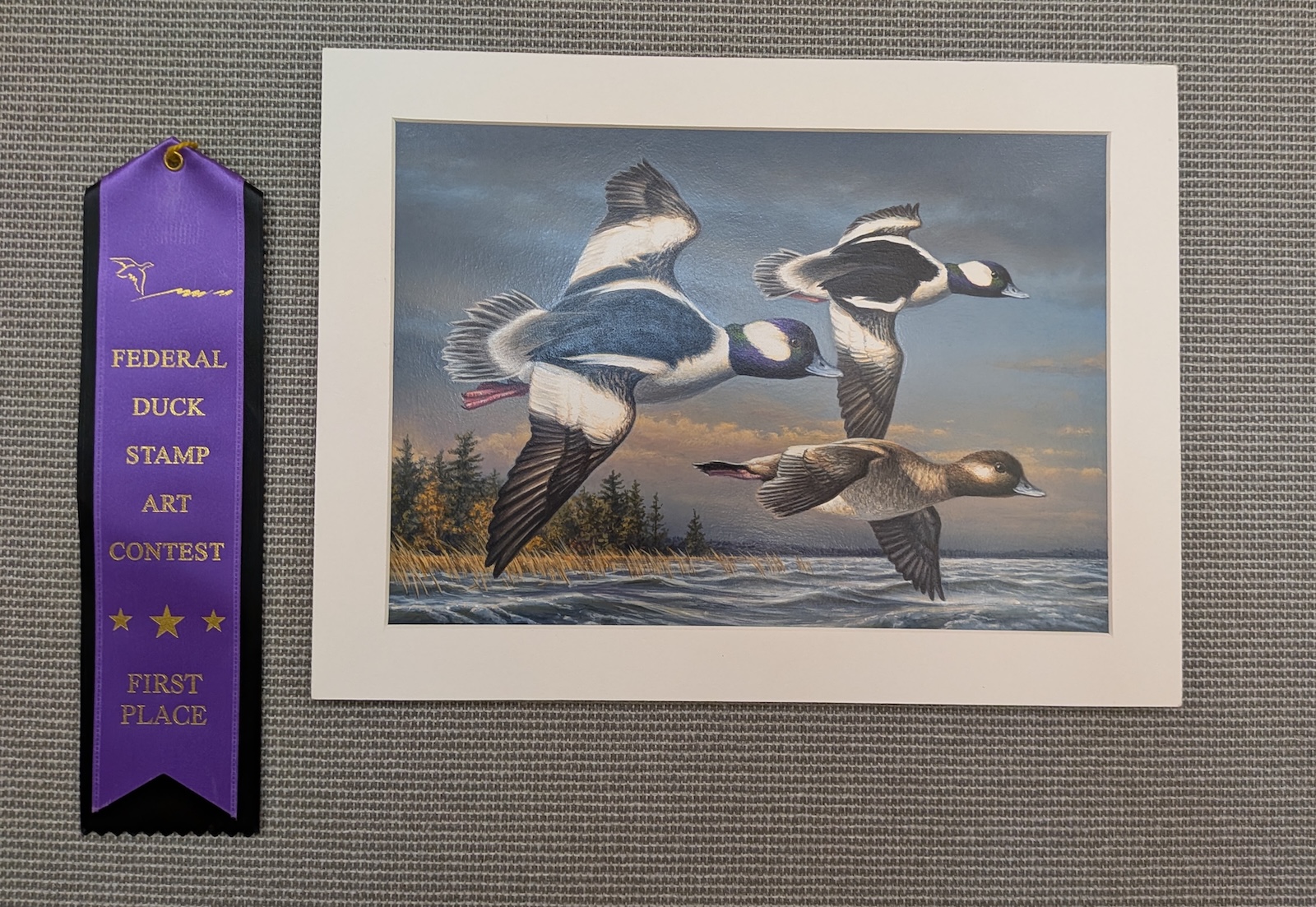

The Federal Duck Stamp Art Contest is the only juried art competition run by the federal government. The winner’s artwork decorates the next year’s duck stamp, which is not a postage stamp, but a hunting license. Revenue from stamp sales funds American wetland conservation with the goal of preserving migratory waterfowl populations.

Although there’s no cash prize for winning the contest, the winner’s art career usually gets a big boost—they can license the image to make merch, sell prints, and gain notoriety in the art world that some spin into cold, hard cash.

“It’s like winning a Grammy in the world of wildlife art,” says artist Michael Kensinger, who’s been entering the contest for 30 years. “You make a lot of money that first year, and for some people it is a career.”

Entrants go to great lengths—learning photography, lying in duck poop, borrowing taxidermied animals—to produce realistic, competitive paintings. Many of the regular entrants have been part of the contest for decades, and hold its traditions dear. But in the past few years, there’s been chatter about a new wave of entrants who are breaking convention by sharing their processes online.

Kira Sabin, a wildlife artist from Minnesota, has been documenting their monthslong painting process on social media—and a lot of non-duck-obsessed people have been following along. Since they started entering the competition in 2019, Sabin has amassed over 313,000 followers on TikTok and 127,000 on Instagram.

“I think people like that I have big goals, but I’m just sitting in my living room and painting a duck,” they say. “It’s cheesy and cute and funny and it’s just a good way to spend your time.”

Sabin says that their social media creations have generated interest in the contest and raised awareness about the stamps’ contribution to conservation. But other artists worry that having a TikTok-famous artist in the mix could make the contest less fair.

In 1934, The Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act went into effect, requiring the purchase of a stamp as a federal license to hunt migratory birds. Conservationist Jay “Ding” Darling created a drawing of a duck to grace the first stamp, and other artists were tapped to create depictions of huntable waterfowl for stamps in the years that followed. In 1949, the first Federal Duck Stamp Contest was held.

This year’s contest is held over two days at the National Wildlife Visitor Center at the Patuxent Research Refuge. To rapidly narrow down the 290 eligible entries, the five judges vote each painting “in” or “out” in the first round. If a painting gets three “in” votes, it advances to round two, where it’s scored from 1 to 5. Despite the adorable subject matter, the in-person judging is dead serious. Each submission to the contest is supposed to be completely anonymous. The judges are revealed the day of the event, and only become aware of each other’s identities the day before.

Jim Hautman, who came to this year’s competition with six duck stamp wins (tied with his brother Joe for the most ever) said anonymity was a factor that attracted him to the competition when he started entering in the mid-1980s. “As a new up-and-comer, I liked that it was judged on its merit rather than, you know, if you go to a gallery or some kind of a juried thing where they know who you are, they’re looking at your resume,” he says. “I found that really appealing.”

Preserving anonymity has led some competitors to discourage others from posting their artwork on social media before the competition. Sitting in a sunny courtyard outside the visitor center on the first day of judging, 2024 winner Adam Grimm says that if the judges recognize these artists’ work on the day of, it could make the competition less fair, or it may at least be perceived that way.

If someone like Sabin, who gets a lot of views on social media, wins the competition, “people would be questioning, did [this painting] win because of its merit or did it win because of the people really like that person?” he says. He knows well how important the nuances of rules can be. When his daughter became the youngest junior duck stamp winner at 6 years old, she was accused of plagiarism, and only exonerated when they could prove that she’d upheld every rule of the contest. “It was so emotionally hard on her,” Grimm remembers.

For some of the more established artists, winning has brought prestige that makes their work more profitable, and keeping the competition “fair” could help keep that within reach. “This is how I pay for everything for our family,” Grimm says of his art, which has been boosted by his three contest wins.

On the flip side, Sabin says being a video creator helps fund their painting—win or lose.

In a breathtaking gallery lined with hundreds of the entrants’ 7-by-10-inch duck paintings, a gaggle of young fans takes selfies with Sabin’s painting of a ruddy duck. It drew its own little audience to the judging, and several younger, female artists said they decided to participate in the contest because they felt encouraged by Sabin’s videos.

“Kira in particular has brought a whole new audience to our program, and these programs need our help more than ever,” Kensinger says.

Each federal duck stamp costs $25, and 98% of the funds go to protecting the wetlands that migratory birds rely on. When hunters buy them, they’re essentially paying a fee to preserve the public land they hunt on, but anyone can buy one to support conservation.

Since the program began, the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has used $1.3 billion from duck stamp sales to purchase or protect over 6 million acres of land critical for waterfowl.

“ I see it as a network,” says Jerome Ford, assistant director of the FWS Migratory Bird Program. “We have to find out where the most valuable habitats are for these birds and other wetland species, and find out how we can make a connection between them.” With deep cuts proposed for the 2026 FWS budget, revenue from duck stamps, which doesn’t depend on entities like Congress or the executive branch, is all the more valuable.

Ford sees engaging the next generation of wildlife enthusiasts as critical to maintaining the longevity of the duck stamp program. His team is encouraging younger people to buy duck stamps by promoting the message of conservation, rather than hunting for sport.

Back at the Patuxent Research Refuge, the tense final round of judging unfolds. A few paces away from the auditorium, the back patio opens up to a small lake, where wood ducks paddle around, and herons fly overhead. The refuge is one of many that was funded by duck stamp dollars, and it’s filled with scenes that would make a great stamp. But inside, only one winner is crowned.

“Jim Hautman?” The FWS announcer reads from the back of the winning painting. The crowd erupts into chuckles and groans. Hautman had taken the prize once again, his seventh.

Despite the quarreling among competitors trying to survive in a changing art market, and the fact that winning is a long shot, pretty much every artist agrees that the splendor of wildlife and the cause of supporting it deeply inspires them.

“ In my opinion, there’s no greater government program for conservation,” Grimm says. “They could have just gone digital, but the fact that they have this art contest and the whole thing, it’s not only great for conservation, but for artists.”

“ I want people to be able to find joy in doing something just because you like it, and [it’s] something that you value,” Sabin says. “My ultimate goal has always been just for more people to know about this conservation tool.”

Emma Lee Gometz was Science Friday’s Digital Producer of Engagement. They wrote SciFri’s “Science Goes To The Movies” series and are a journalist and illustrator based in Queens, NY.