An Ice-Cold Octopus Nursery Could Help Expand Marine Protections

Indigenous and Western scientists are working together to uncover biodiversity in the icy deep. They’re getting some eight-armed help.

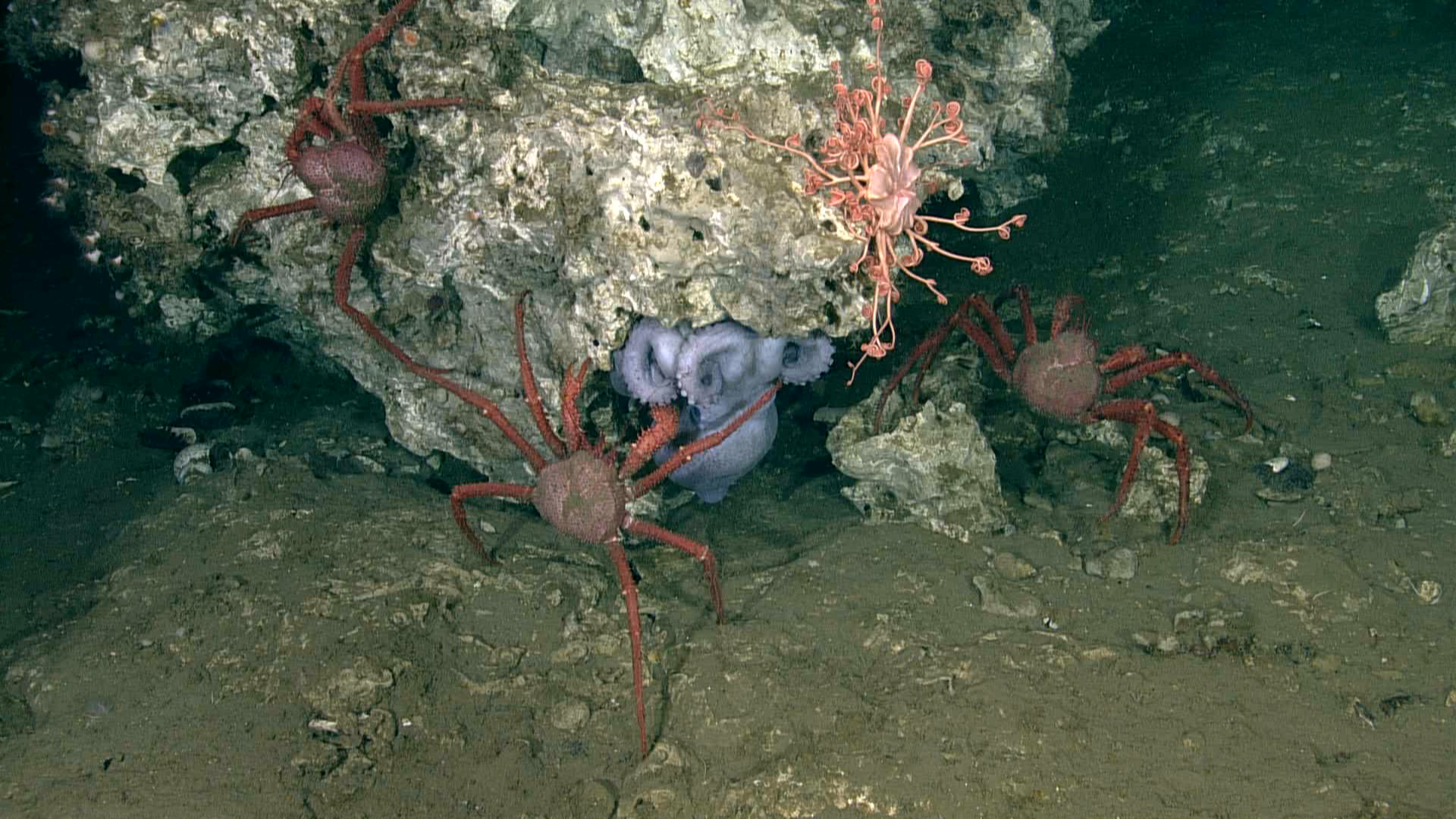

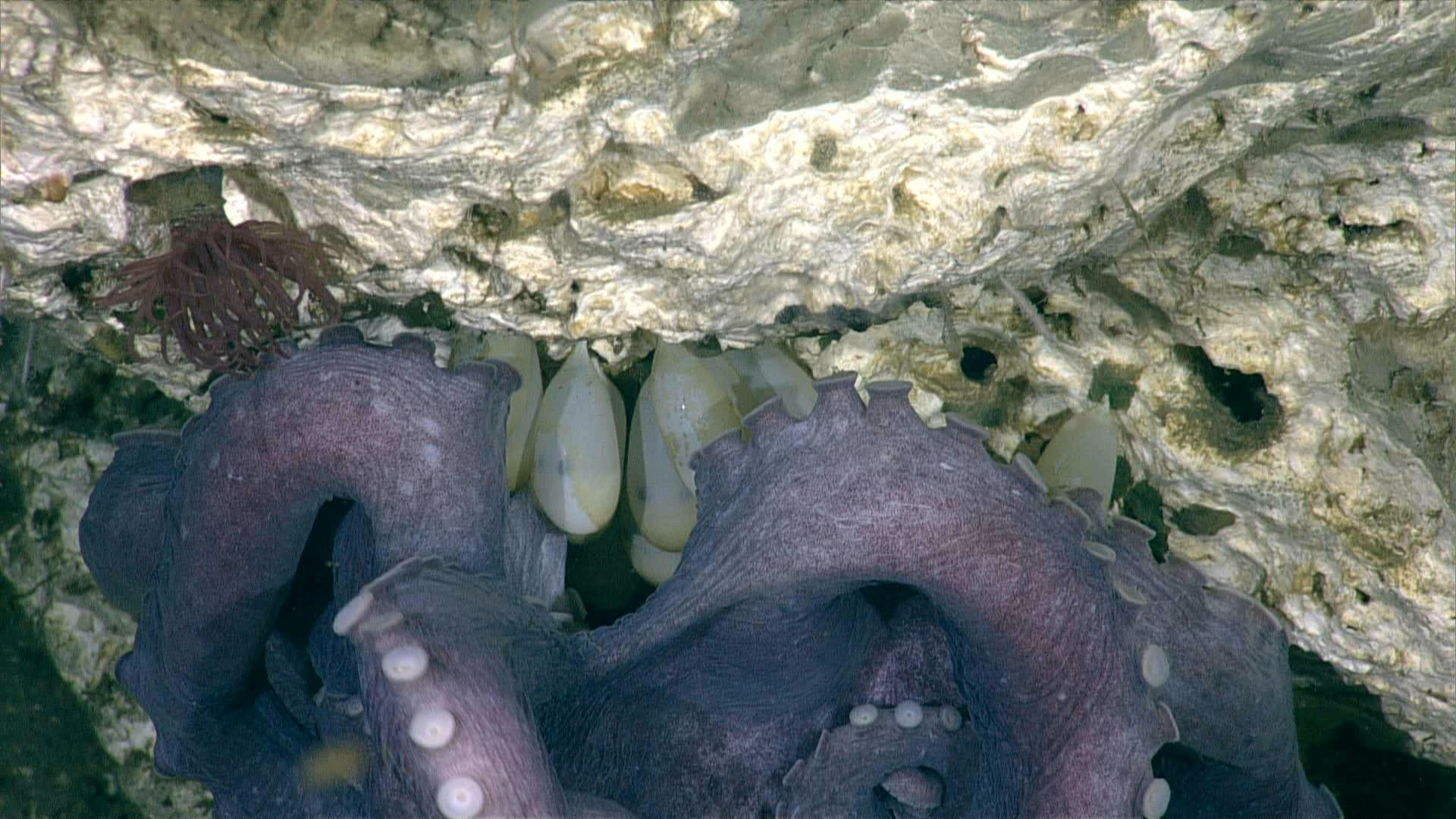

An Pacific warty octopus mom fights off multiple crabs to protect her eggs at an octopus nursery discovered off of Vancouver Island, Canada, in 2023. Credit: Northeast Pacific Deep-sea Expedition partners and CSSF ROPOS

Two years ago, Dr. Cherisse Du Preez sent an underwater drone to the bottom of the sea expecting to find worms. Instead, she stumbled upon an army of octo-moms.

Du Preez is a marine biologist and head of the Canadian federal government’s Deep Sea Ecology Program. Just before a 2023 expedition to explore cold seeps—spots where chemicals like hydrogen sulfide and methane seep through fissures on the ocean floor—Du Preez received a tip from a colleague that bubbles were shooting rapid-fire from a spot about 90 miles from Vancouver Island. She made a pit stop there, expecting to find straw-like bottom-dwellers called tubeworms—but what she saw looked like an alien landscape.

Bubbles of methane surging from an underwater mound had reacted with seawater and bacteria over time to create craggy carbonate rock formations and iceberg-like boulders. When the team descended further into this crevice-filled terrain, “you just saw mom octopuses everywhere,” Du Preez says. “That’s when we knew we had found something that wasn’t just geologically special, but that was having these convoluted cascading effects that ended up creating what, at the time, was the fourth known octopus nursery in the world.”

Octopus nurseries, also called octopus gardens, are rare deep-sea habitats where female octopuses, which are typically solitary creatures, gather in groups of dozens up to thousands to mate and tend to their eggs. Only a small handful of such nurseries are currently known throughout the world—others are located off the coasts of California and Costa Rica.

Some of these known nurseries are positioned near hydrothermal springs that heat the water. Researchers don’t know exactly what attracts octopuses to specific nursery locations, but in some cases, warmth might play a role, providing something of a metabolic jump start for babies. And, research shows that water temperature affects brood times.

“In shallow, tropical waters where octopuses breed, they lay many, many eggs, sometimes hundreds of thousands of eggs, but they’re typically small eggs that develop very rapidly, a matter of a few weeks at most,” says Dr. James Barry, a marine ecologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute who was not involved in Du Preez’s work. “The deeper you go and the colder the water is, typically, the larger the eggs are. They lay fewer eggs and they take far longer to brood.”

In the ocean’s depths, brood times can be shockingly long. For example, Graneledone pacifica, sometimes called the Pacific warty octopus, has the longest known brood times of any animal on Earth. They tend their eggs for up to four years or more, forgoing food the entire time, then die shortly after the eggs hatch. But in toastier octopus nurseries, research shows that brooding is likely much shorter: Barry’s research has shown that at a nursery over a hydrothermal spring nearly two miles beneath the ocean surface, pearl octopuses had brood times of roughly 1.8 years—much faster than would be expected for a deep-sea species.

The Vancouver nursery Du Preez’s team discovered, which is within a cold seep that’s roughly the same temperature as the surrounding water, shows that warmth isn’t the only force attracting octopuses to their gardens. It’s not clear why hundreds of Pacific warty octopuses come to that particular place, though Du Preez speculates that it could be due in part to the caves and crevices created by the seep’s intricate rock formations—full of surfaces to anchor eggs onto and hidden dens for protective cephalopod parents.

While researchers have long known that cold seeps are biological hotspots, “we’ve been kind of limited in how far that extended. It seemed like they were little islands unto themselves,” she says. “You introduce the octopus and animals like the octopus that are actually using these habitats in ways that we never considered before, and now we’re realizing that [cold seeps] are so much more linked to the larger deep sea and even the larger planet.”

Du Preez calls the garden “the tip of the iceberg,” providing just a taste of the wonders scientists have yet to uncover in the ocean’s greatest depths. A study published earlier this year in Science Advances that compiled data from approximately 44,000 deep-sea dives—the most comprehensive such study to date—estimated that researchers worldwide have visually observed less than 0.001% of the deep ocean. That’s an area roughly the size of Rhode Island.

Now, Fisheries and Oceans Canada is working with several First Nations of British Columbia to protect cold seep biodiversity, including the octopus nursery, by providing science advice for a potential new marine protected area. If officially created, the new marine protected area would be Canada’s second largest, and would bring the country a significant step closer to fulfilling its pledge to designate 30% of the nation’s oceans as protected spaces by 2030.

Ties between Nuu-chah-nulth communities and the sea “is a connection that dates back millennia,” says Irine Polyzogopoulos, the communications and development coordinator for the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council’s Fisheries Department, one of the First Nations partners. “We talk about the Nuu-chah-nulth’s principle of hišukʔiš c̓awaak, which translates to ‘everything is connected, everything is one.’… What we do to protect the ocean, it all ties into fisheries that communities rely on for food and economic resilience.”

Coastal Indigenous communities have long worked with the Canadian government on marine protection initiatives aimed at fisheries. But collaborations around deep ocean research only started in 2015, Polyzogopoulo says. That’s when the government and several Indigenous groups began creating the country’s largest protected region—an expanse that’s about twice the size of Maryland and is cooperatively managed by the government of Canada, the Council of the Haida Nation, the Pacheedaht First Nation, the Quatsino First Nation, and the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council. In 2024, it was officially designated as the Tang.ɢwan—ḥačxwiqak—Tsig̱is Marine Protected Area.

These partnerships and protected spaces are vital, Du Preez says, especially as climate change and human activities, like underwater mining, threaten to permanently alter or eliminate unexplored deep-sea wonders, including octopus nurseries.

“As we’re moving forward with all the deep-sea emerging activities, we have to consider what we don’t know,” she says.

Christina Couch writes about brains, behaviors, and bizarre animals for kids and adults. Her bylines can be found in The New York Times, NOVA, Smithsonian, Vogue.com, Wired Magazine, and Science Friday.