The Mysteries Of Freshwater Jellyfish

7:08 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Ellie Katz, was originally published by Interlochen Public Radio.

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Ellie Katz, was originally published by Interlochen Public Radio.

In 1933, a high schooler fishing along the Huron River in Ann Arbor, Michigan looked into the water and saw something weird. It turned out to be a freshwater jellyfish – the first ever discovered in the Great Lakes region. Later that year, there was another sighting in Lake Erie.

Researchers think the species hitched a ride here on aquatic plants shipped from China, then spread. But there’s no evidence they harm the lake ecosystems they now call home.

Since then, the jellyfish have spread across the Upper Midwest, loitering mostly in inland lakes, rivers, and streams. But we still don’t know all that much about them.

A biology professor and her field research class at Eastern Michigan University are hoping to change that. Every week, they slap on masks, snorkels, and floaties, and wade out into a southeast Michigan lake on the lookout for jellyfish.

What they find could lay the foundation for more research on freshwater jellyfish, and change how we think about invertebrates in the process.

Ellie Katz is an environment reporter at Interlochen Public Radio in Interlochen, Michigan.

DESSA: Nothing complements a jellyfish story like another jellyfish story. So let’s take this show on the road to learn about the jellies of Michigan, as we check in on The State of Science.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: This is KERA.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: For WWNO–

RADIO ANNOUNCER: St. Louis Public Radio News.

RADIO ANNOUNCER: Iowa Public Radio News.

DESSA: Local science stories of national significance.

Now, when I think jellyfish, I think of salty ocean waves or maybe that sitcom sketch, where somebody on the beach desperately seeking relief from a sting begs a friend for help. And no, that home remedy does not work, dear listeners. But it turns out that there are some 20 species of freshwater jellies around the world. And one of them, originally native to the Yangtze River in China, has been spreading around the US for about 100 years.

Ellie Katz is an environment reporter at Interlochen Public Radio. She reported on a student effort in Michigan to learn more about these freshwater jellyfish for the Points North podcast.

Ellie, welcome to Science Friday.

ELLIE KATZ: Thanks, Dessa. Great to be here.

DESSA: OK. Tell me more about these freshwater jellyfish. What are they? What are they doing?

ELLIE KATZ: Yeah, it’s a good question. They’re not doing much, honestly. They’re kind of loitering. And they’ve spread to about every continent on Earth except Antarctica. So they’re pretty prolific. And they like calm water– slow-moving rivers, lakes, quarries, ponds, places like that. They’re pretty small, about an inch across at most.

But because they can survive in a lot of different types of waters and have a pretty broad range of water temperature, they’ve managed to spread. They think that they hitched a ride over on ornamental aquatic plants brought to the US in the early 20th century. And yeah, like you said, they’ve been hanging out in the US and over the world for about a century now.

DESSA: Pause– ornamental aquatic plants– what are you talking about?

ELLIE KATZ: So things people would use to decorate their personal ponds or gardens, things like that.

DESSA: The question that probably comes to everybody’s mind, first and foremost, is, if we are living amongst them, can they sting?

ELLIE KATZ: Yes, they can, but just not you and me. Like most jellyfish, they’ve got stinging cells, but their tentacles are too small for humans to feel so. Like I said, they’re about the size of a nickel. They will sting their prey– typically, zooplankton or tiny water fleas– just small water animals. But no, you and I wouldn’t feel the sting if they did brush against us during a morning swim.

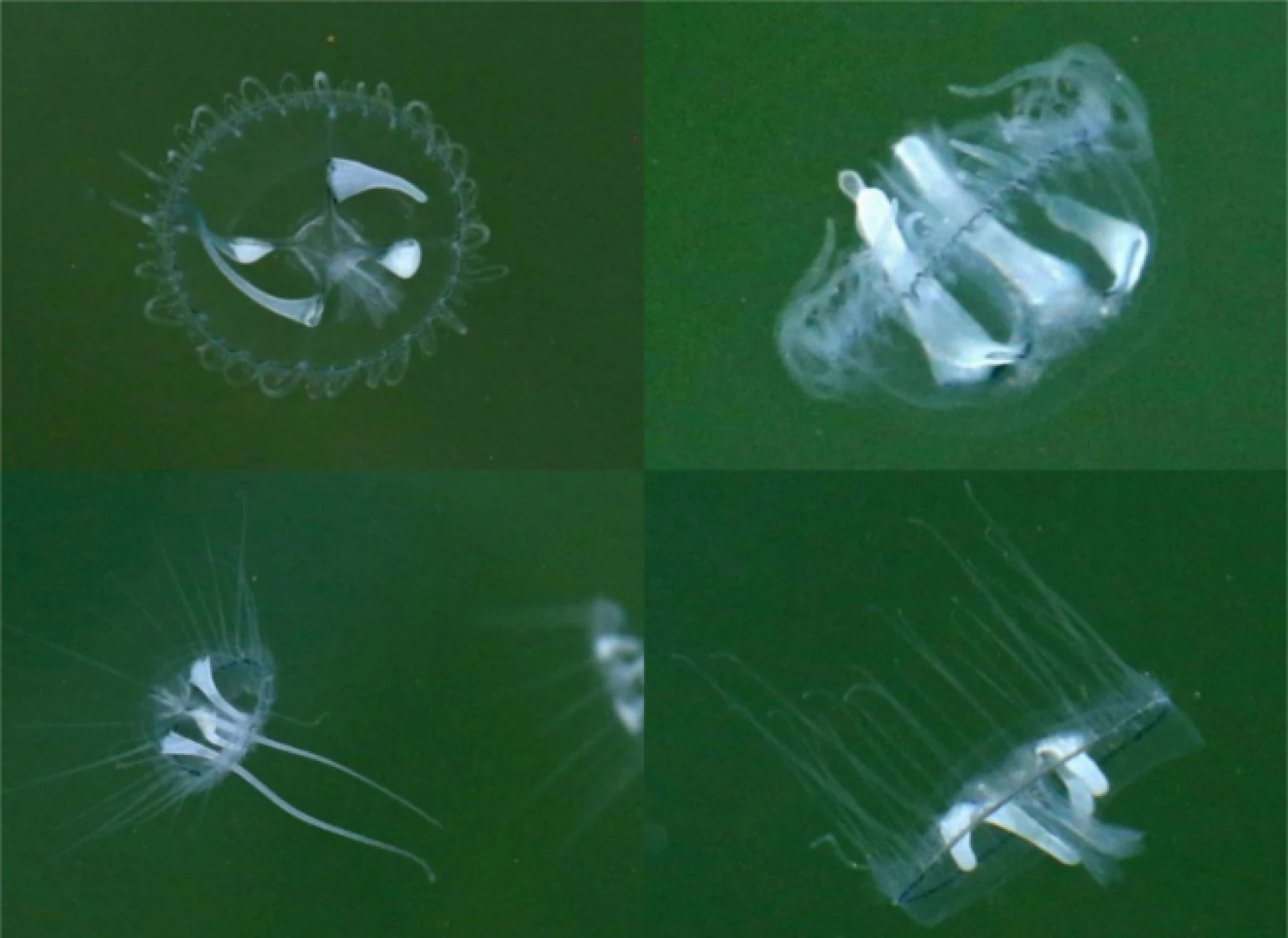

DESSA: In the story that you covered, as you describe what they actually look like– I mean, they’re large enough to be easily seen with the naked eye– but they’re kind of translucent, right? So are they tough to spot in the water?

ELLIE KATZ: Yeah, they are pretty tough to spot. But it’s one of those things where, once you see them, you can’t unsee them. This woman on the beach who I spoke to described them as unmistakably jellyfish. And she was so right. They are these beautiful little creatures pulsating in the water, translucent, with a white ring around this beautiful bell shape and, yeah, little tentacles just powering them through the water.

DESSA: I know that a lot of times when we talk about the arrival of a new species, we’re worried about an ecological disruption. Is that a concern here with these freshwater jellyfish?

ELLIE KATZ: It’s not as much of a concern right now. We’re no stranger to invasive species in the Great Lakes. And the problem with a lot of those invasive species is that they’re eating tons of food that’s low on the food chain– things like zooplankton, phytoplankton– the same things that these jellies are eating. But because these jellies pop up so sporadically– like there’ll be hundreds of them in one lake in one year, and then the next year they’re entirely gone– they’re not really causing enough harm.

They’re not consistently there, eating huge bricks of the bottom of the food chain every year. So they’re not causing any demonstrable harm or benefit right now. They’re just kind of loitering, hanging out. But there still needs to be more research to figure out where they are, when they’re popping up, how many there are, and what’s affecting these different blooms– as they call them– these big groups of them that occasionally pop up.

DESSA: And you mentioned that you went out personally with a class that was studying some of these jellyfish. What is the objective of their research? What are they trying to discover?

ELLIE KATZ: Yeah. I mean, it’s nothing groundbreaking, but it is really important because there’s so little research on these guys. So I went out with a classroom of Eastern Michigan University, some undergrad students, some graduate students, mostly studying biology. They’re really just trying to get basic data. They’re trying to figure out how best to collect the jellies, whether that’s with a jar or a bag. They’re trying to figure out how to measure them. They’re recording where they show up in the lake, when, what the temperature is when they pop up.

And the idea is that, when they’re able to get this long-term data about the jellyfish, they can detect changes or patterns over time. And that will be able to tell us whether they are having a meaningful effect on food availability in this lake. And we could learn why they spread out when they do, what affects whether they’ll show up or not in any given year. That kind of stuff.

DESSA: OK. So if this species is so widespread, then why don’t we know very much about them already?

ELLIE KATZ: Well, there’s a few reasons, One you kind of got at. And it’s that they’re hard to notice. Unless you’re going really slowly in a lake or a slow-moving river and looking down and at the right time with the right conditions, they’re pretty easy to miss. And then they’re also really unpredictable. So some years they’ll show up in the hundreds in one lake, and then the next year there’s none.

But the biology professor who’s leading this class at Eastern Michigan University– her name is Cara Shillington– she thinks there’s another reason, too. And she thinks it’s just that people aren’t as interested in invertebrates as they are in studying vertebrates. Invertebrates like jellyfish aren’t as sexy or as lovable as many vertebrate species.

There’s maybe not a ton of science kids dreaming about studying worms or insects. But invertebrates are pretty foundational to animal life here on Earth. And Cara told me that one hope she has for the class is that these jellies, which are pretty charismatic and interesting invertebrates, will serve as a gateway to get more students excited about invertebrates.

CARA SHILLINGTON: How can you not love them? The diversity is just amazing. The varieties of lifestyles, of what they do, of how they look, of their structure is just absolutely phenomenal. How can you ignore 99% of the animal world and focus on just 1%? How can you not want to know more?

DESSA: You’re calling them “jellies,” not “jellyfish.” Is that just the cool field slang?

ELLIE KATZ: No. That’s actually a good question. It is the cool field slang, but there is good reason for it, which is that “jellyfish” is a little bit of a misnomer, since they’re not actually fish at all. And so scientists who I’ve spoken to tend to call them “jellies” instead.

DESSA: I dig it.

Ellie Katz is an environment reporter at Interlochen Public Radio. She reported this story for the Points North podcast. Thanks for joining me today, Ellie.

ELLIE KATZ: Thanks, Dessa.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.

Dessa is a singer, rapper, writer, and professional speaker about art, science, and entrepreneurship. She’s also the host of Deeply Human, a podcast created by the BBC and American Public Media.