Trees And Shrubs Are Burying Prairies Of The Great Plains

12:07 minutes

This article is part of The State of Science, a series featuring science stories from public radio stations across the United States. This story, by Celia Llopis-Jepsen, was originally published by KCUR.

STRONG CITY, Kansas — Flint Hills rancher Daniel Mushrush estimates that his family has killed maybe 10,000 trees in the past three years.

It’s a start. But many more trees still need to fall for the Mushrushes to save this 15,000 acres of rare tallgrass prairie.

Whenever other work on the property can wait, Daniel and his brother, Chris, don helmets and earplugs, grab their tools and pick up where they left off.

“It’s a lot of old-fashioned chainsaw work,” Daniel Mushrush said. “Walking rocky ridges and cutting down trees.”

The Mushrush family is beating back a juggernaut unleashed by humans — a Green Glacier of trees and shrubs grinding slowly across the Great Plains and burying some of the most threatened habitat on the planet.

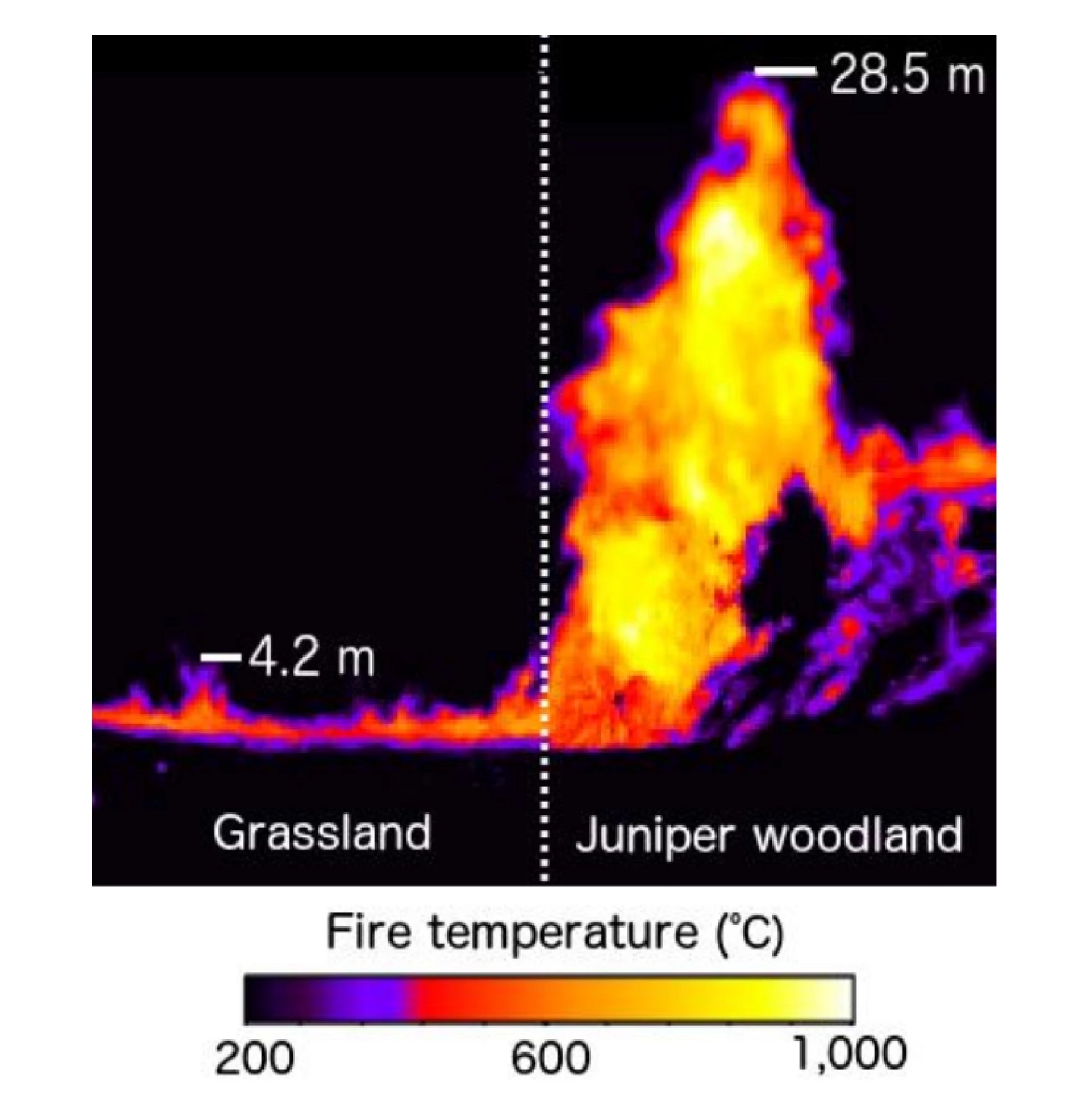

This blanket of shrublands and dense juniper woods gobbling up grassland leads to wildfires with towering flames that dwarf those generated in prairie fires.

It also eats into ranchers’ livelihoods. It smothers habitat for grassland birds, prairie fish and other critters that evolved for a world that’s disappearing. It dries up streams and creeks. New research even finds that, across much of the Great Plains, the advent of trees actually makes climate change worse.

Now a federal initiative equips landowners like Mushrush with the latest science and strategies for saving rangeland, and money to help with the work.

Satellite imagery and a better understanding of how trees and shrubs spread could help landowners replace a losing game of whack-a-mole with a more systematic course.

Mushrush calls the approach, promoted by the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Great Plains Grassland Initiative with guidance from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, a morale builder.

“It works,” the third-generation rancher said. “We’re still overwhelmed with how to do this on 15,000 acres — but we have a plan.”

Each time he thinks about the Manhattan area, which is much more infested with juniper woods and seas of sumac, wild plum and dogwood thickets, he feels the threat creeping toward his home in Chase County.

“If a coral reef is worth saving, if some pristine mountain stream is worth saving, then so are the Flint Hills,” he said. “It’s not easy work, but it’s worthy work.”

Until recently, it seemed the iconic tallgrass landscapes of Chase County couldn’t possibly suffer the same fate as those around Manhattan. But satellite imagery of the Green Glacier’s expansion proved this is untrue.

“We realized we weren’t immune to it,” he said. “It was coming.”

An image of the Great Plains lingers in cultural consciousness: A place of vast, largely treeless horizons.

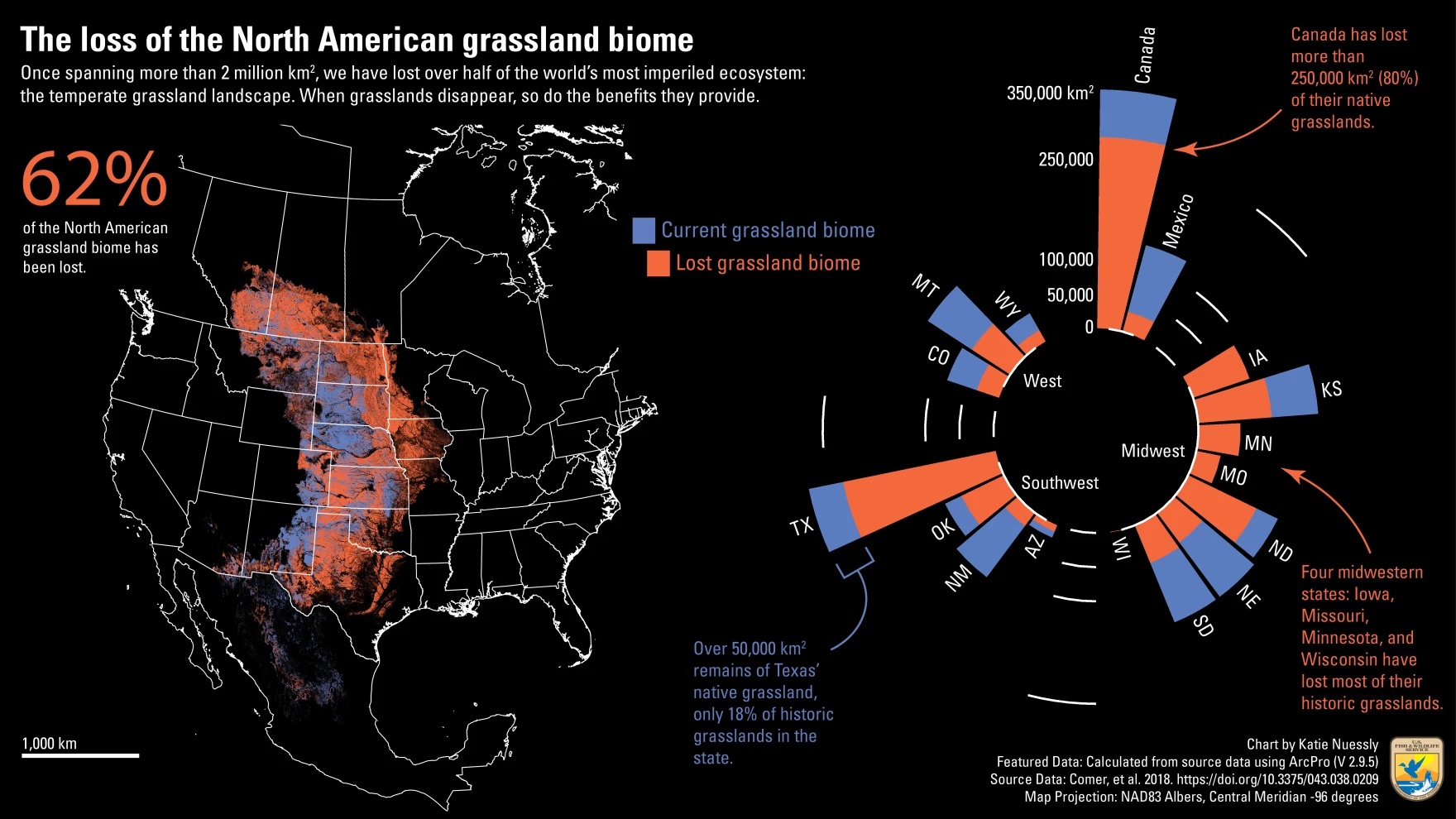

Grassland once covered one-third of North America.

Today’s precious, remaining regions of relatively intact prairie — places that somehow survived becoming cornfields and suburbs — now face steep odds.

“It is disappearing right in front of our eyes,” said Jesse Nippert, a professor and grassland ecologist at Kansas State University. “It’s happening everywhere on the planet.”

The phenomenon transforming grassland worldwide is called woody encroachment.

In North America, scientists at Oklahoma State University came up with the term “Green Glacier,” painting the image of a blanket of woody plants unfurling gradually but devastatingly across the center of the continent.

Even the Flint Hills have proven vulnerable, despite so many ranchers there conducting controlled burns for decades.

The threat is well known among ranchers, but even Midwesterners who rarely visit rangeland can likely spot the signs of change close to their homes.

Just look for the evergreens: Eastern red cedars are a juniper species with a misleading moniker.

The often rust-tinged conifers flank Interstate 70 and invade underused pastures and abandoned lots on the edges of towns and cities. They create dense woods and borders that swaddle semi-rural housing developments, ranchettes and hobby farms.

Long beloved and still frequently planted for the shelter they provide against wind and snow, the species is doubtlessly the most controversial tree in the region, sometimes causing frustration among neighbors.

If you’ve bought a slice of rural heaven to enjoy deer hunting or escape suburban life and the eyes of neighbors, you may well prize eastern red cedars.

If you’re a rancher, you likely hate them.

The trees are the single most prominent symbol of woody encroachment in the center of North America.

They’re spoiling grassland particularly fast in parts of Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Iowa, Missouri and South Dakota. The University of Nebraska-Lincoln launched a public education campaign devoted to sounding an alarm about the species.

To prairie conservationists, an eastern red cedar has one redeeming quality: It dies if you chop it down or set it on fire.

Other headache plants, such as American plum and rough-leaf dogwood bushes, don’t surrender so easily.

K-State scientists study every imaginable aspect of woody encroachment at the Konza Prairie Biological Station outside Manhattan.

They tried restoring infested tallgrass prairie by burning it 23 years in a row.

“Those shrubs are still everywhere,” Nippert said. “In fact, they expanded.”

That makes shrubs the single biggest danger to the Flint Hills, he said. Uninfested land must be burned every other year to keep them out.

After shrubs establish themselves, they become nearly unstoppable without spot-spraying herbicides.

The Green Glacier has edged out billions of pounds of grass in the United States. To ranchers, that’s a production loss. The land feeds fewer cattle.

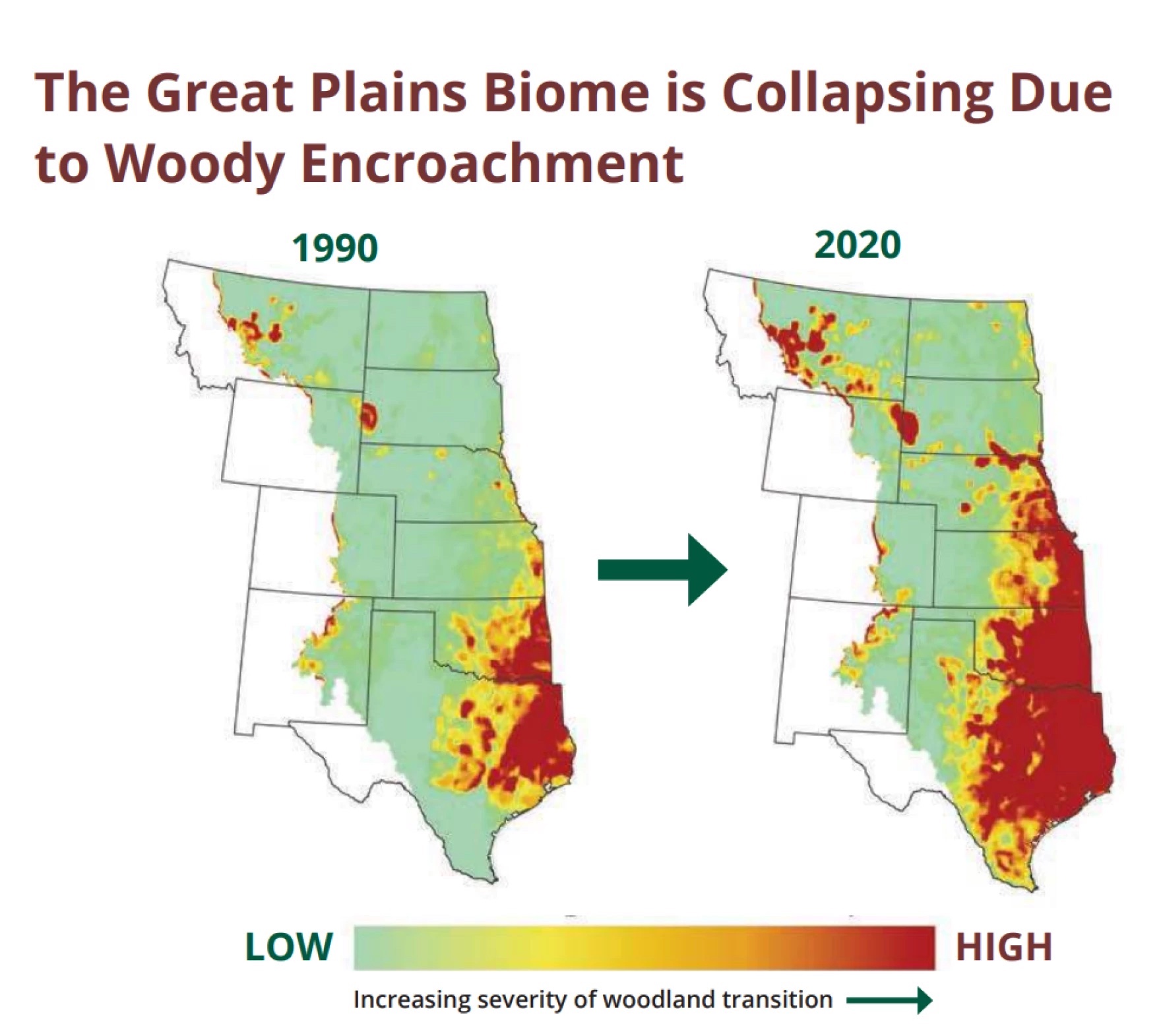

To communicate the scale and speed of that loss, rangeland ecology professor Dirac Twidwell at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln compares the Flint Hills as it looked in the 1990s versus today.

The Flint Hills could grow about a billion more pounds of grass annually if it weren’t for how many trees and shrubs have taken root since then, he explained in an overview of the situation for Kansas landowners.

Picture all that grass rolled into giant, round hay bales.

“You could line those up side by side from Kansas City, Missouri,” he said, “and drive 9 hours seeing nothing but round bales all the way to Denver.”

Yet the sumacs, elms, plums, junipers and other woody plants spreading today have existed in the center of the continent for ages. They are mostly native species with their own ecological contributions.

What spurred them to proliferate so dramatically that they now threaten prairie flora and fauna, leading Twidwell and other scientists to conclude the grassland biome is collapsing?

The story of the Green Glacier unfolded over the past few centuries.

Humans have shaped North American ecosystems for millennia. And for a very long time, their way of managing the land helped foster the continent’s vast grasslands and prairie animals — primarily through the use of fire that kept trees at bay and made for excellent hunting.

More recently, humans began tipping the scales in favor of shrubs and trees.

It started after the arrival of Europeans and, ultimately, the U.S. government actions that decimated Indigenous populations and forced them from nearly all of their territory.

That simultaneously eliminated fire-based land management from much of the continent’s grasslands. The newcomers also eventually eliminated elk — massive, shrub-eating browsers — from much of their range.

Settlers came from countries and regions without vast grasslands. They valued trees over prairies and planted them at sometimes mind-bogglingly large scales.

Trees blocked wind, provided wood for construction and made the plains more hospitable to their ways of life.

In 1872, Nebraskans planted a million trees in a single day, the origin of Arbor Day. A few decades later, people there created what is today the biggest hand-planted forest in the Western Hemisphere.

Later, overfarming, drought and heat triggered the 1930s Dust Bowl.

The federal government, which had already encouraged and incentivized settlers to plant trees and hedgerows, sped up the work to protect soil and crops.

Meanwhile, humans had also industrialized the economy. Churning ever more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere spurred shrubs and trees to outcompete grasses.

“It’s more than a key contributor,” Nippert said of the role that increased CO2 plays in woody encroachment. “It’s probably the main reason.”

The federal government has over the years poured many millions of dollars into tackling woody encroachment piecemeal.

Landowners would restore what effectively amounted to scattered patches of grassland already thoroughly invaded or surrounded by trees.

“We just have more and more and more sites to treat over time,” Twidwell said. “We just don’t have the money and expenditures to continue that game plan. That experiment failed.”

Trying to save pasture in such steep decline requires the most expensive methods: Heavy machinery, long hours and herbicide by the barrelful. But in many areas, bulldozing trees and shrubs offers only temporary gains at best.

The seeds of the woody plants lay on the ground, ready to sprout a new generation. Birds swoop in with even more seeds from adjacent land.

The new approach is called “defending the core.”

Twidwell and his colleagues urge landowners to start their work in the healthiest grassland they have available — ideally areas with few to no woody plants. Next, work outward. Kill trees and shrubs along the way to create an ever wider expanse of contiguous, cleaned-up prairie.

Studies of eastern red cedars reveal a basic fact about how they spread: 95% of the time, their seeds sprout within a distance of two football fields.

In other words, American robins and other critters with a taste for juniper berries don’t travel all that far between feasting in a juniper tree and pooping out the seeds.

That’s good news to Twidwell.

“We can manage football fields,” he said.

By clearing an area and expanding outward, landowners can increase the acreage that is at least two football fields away from the nearest trees.

Ultimately, the zone becomes easier to protect with controlled burns. Prescribed fire is cheaper and safer than heavy machinery and chainsaws.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service — part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture — has thrown its weight behind the new approach.

It launched the Great Plains Grassland Initiative to help ranchers ramp it up in Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and South Dakota.

By the end of this fiscal year, the program will help protect nearly 220,000 acres of grassland in Kansas alone, providing financial help and technical expertise to landowners.

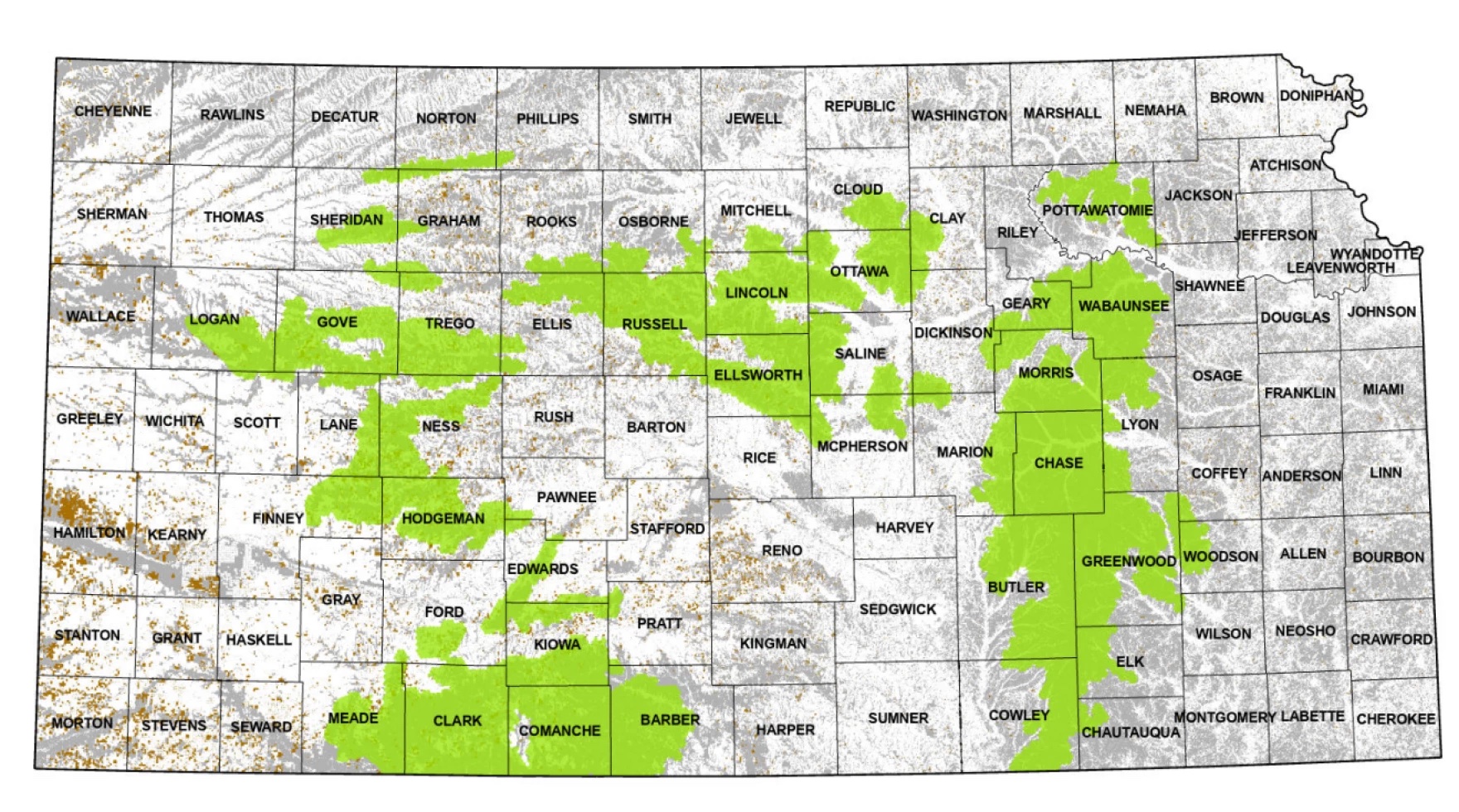

The initiative homes in on relatively intact prairie regions where ranchers want to stop the Green Glacier and where progress could pay big dividends for the wildlife.

In Kansas, that means focusing on the Flint Hills, the Gypsum Hills, the Smoky Hills and certain other areas. Those ranching strongholds fuel America’s beef industry and support hundreds of species of plants and animals.

The Rangeland Analysis Platform, a tool created by the University of Montana and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, provides detailed satellite imagery that shows ranchers where woody plants have spread over the years.

That spells out their losses and helps them strategize.

Fires happen.

When not enough controlled burns take place, wildfires become more severe.

When they strike rural areas and suburbs packed with drought-stressed eastern red cedars that contain volatile oils, the flames can travel quickly from the ground into tree crowns and onto rooftops.

One fire captain in Hutchinson described the trees as Roman candles spewing embers that can hitchhike on wind and land a quarter mile away, starting more blazes.

Juniper woods can produce 90-foot-tall flames, compared to flames under 15 feet in a grassland wildfire, University of Nebraska-Lincoln scientists say.

In March 2022, wildfire struck more than 6,000 acres near Hutchinson, killing one person and destroying more than 100 buildings, including 36 homes.

The juniper trees crowding the area made it hard to stop the flames, a state task force on wildfire concluded.

Gov. Laura Kelly created the task force in 2022. Extreme wildfires have become impossible to ignore.

Red cedars played the same amplifying role in the state’s two biggest recorded blazes, both of which struck within the past decade.

The Anderson Creek fire burned nearly 400,000 acres in Kansas and Oklahoma. A year later, 2 million acres of Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas burned in the Starbuck fire and other blazes at the same time.

The amount of land that burns each year in major wildfires on the Great Plains increased fivefold in the last 30 years, University of Nebraska researchers found.

Those are the kind of uncontrollable fires that the Mushrush family wants to avoid — yet another reason to slow the Green Glacier’s march into Chase County.

Likewise, they want to save precious creeks and streams at risk of disappearing.

Trees and shrubs use three times as much water as tallgrass does, Nippert from K-State says. Even worse, their thick roots drill holes that irreparably change how rainwater flows.

As they shatter the Flint Hills’ famously rocky ground, rainwater pounding the prairie sinks deep into the earth instead of traversing it and funneling into creeks and streams. Water disappears beyond the reach of both wildlife and livestock.

At the Konza research station, K-State scientists have watched streams get drier even as precipitation increased.

In 2010, they removed trees from a long swatch of watershed to see if they could restore flow. It didn’t work.

Last year brought the Mushrush ranch in Chase County its worst drought in a decade.

The family took heart when a creek that had dried up in the 2012 drought kept flowing where they had removed trees.

“Seeing the water flow through a stream,” he said, “You can see the results and go, ‘Hey, we did good.’”

Nippert, at K-State, fears much of the Flint Hills is now so fractured from tree and shrub roots that this kind of intervention won’t help.

“Mushrush and the people in Chase County are lucky,” Nippert said. “Do what you have to do to keep it the way that it is — before it transitions.”

Celia Llopis-Jepson is the host of “Up From Dust” from KCUR Studios in Kansas City, Missouri.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: This is Science Friday. I’m Sophie Bushwick. And now it’s time to check in on the state of science.

SPEAKER 1: This is KERA.

SPEAKER 2: For WWNO–

SPEAKER 3: St. Louis Public Radio.

SPEAKER 4: Iowa Public Radio News.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Local science stories of national significance. Since grade school, I’ve been told that planting trees is the height of environmentalism. Plant a tree– save the planet, right? Well, it’s a little more complicated than that.

Trees don’t actually belong in every biome. And in some cases, they can be downright bad. That’s the case for the Great Plains, where a wave of trees and shrubs is burying this threatened habitat. Joining me now to talk about this is my guest, Celia Llopis-Jepsen, host of the podcast, Up From Dust, from KCUR Studios in Kansas city, Missouri. Welcome to Science Friday.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Great to be here.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Let’s talk about the Great Plains prairies. What makes this ecosystem so special?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah, so there is really nothing like standing on a healthy prairie where you can see this kind of ocean of grass and wildflowers that stretches all the way to the horizon. These are really special places with their own wildlife, including some very cool animals that were once widespread on this continent and just aren’t anymore– highly specialized grassland birds, prairie chickens.

What I love about grasslands, for listeners who maybe haven’t set foot in a place like this, is it’s a really kind of amazing combination of awe and subtlety. You have the awe of looking at the prairie stretching for miles in front of you, and then this subtlety that it may look all the same at first glance, but actually it’s full of all these rich and wonderful details.

And I live close to what’s left of the vast tallgrass prairie, which isn’t much that’s left at this point. And the National Park Service calls this one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. But there are just fewer and fewer places where you can see a healthy, tallgrass landscape.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I mean, I love that description of this as an ocean of grass. But just how big were the North American grasslands back in the day? And then how does that compare to today?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah. I mean, it’s hard to picture. But the easiest way to think of it is that one third of North America used to be grassland.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Wow.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Just really vast. We’re talking in the center of the continent, all the way from a little bit in what’s now Mexico, up through states like Kansas, Nebraska, Montana, up into Canada. And within that, a whole lot of ecological variation. So in Eastern Kansas, you have tallgrass prairie that looks and feels very different. As you go west towards the Rockies and eventually transition into what’s called shortgrass prairie, these are all their own very special places. But, yes, it is very much shrinking because of the trees and the shrubs that you referenced in the introduction.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And in your reporting, you call this a quote unquote, “green glacier that’s eating up grassland.” So what specific kinds of plants are we talking about here?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah, so I love this term because I think it really paints a picture. Green glacier is a term that comes from scientists at Oklahoma State University. You can imagine this gradual glacier plowing right across the center of the country, just burying prairies.

And it’s a lot of Juniper trees. They’re called Eastern red cedars, but they’re these dense Juniper trees and really aggressively spreading shrubs, like dogwood thickets and sumac, that are infesting, invading, what’s left of North American prairies– because I do want to be clear, North American Prairie’s have largely become farmland. But what’s left of the continent’s prairies is in real trouble now. It’s transitioning into woodland and shrubland.

So Kansas State University studies this super in-depth. So I went to one of their grassland ecologists to wrap my head around this, Jesse Nippert. And this is what he had to say.

JESSE NIPPERT: As a naturalist and a conservation person, I want the grasses back. But it’s these areas that have turned into juniper forests– we’re probably not going to get them back. I think we protect what we can protect. We try and restore the areas that can be restored.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: And a big thing to note here is this isn’t just North American prairies that are collapsing. Scientists are seeing the same phenomenon in grasslands all around the world.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And how did these trees and shrubs grow in such huge numbers?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Well, humans have changed the atmosphere. So what Jesse Nippert explained to me is that more carbon dioxide in the air literally means photosynthesis in these trees and shrubs gets more efficient. So here’s what happens. Fires on the prairie, often started purposefully by Native Americans, used to keep woody plants in check. But now, trees and shrubs can grow taller in a single year than they could when there was less CO2 in the air.

So you have dogwood thickets and things growing taller, faster. They shade out all the grass around them. And when they do that, they protect themselves against fire. So the next time a fire comes through, basically they’ve removed the grass around them that catches fire so easily so that they can survive better and keep growing taller and taking over the prairie.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And what are the consequences of that happening, of this takeover where grasslands are lost to trees and shrubs?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: For ranchers, this is a matter of their livelihood. As grassland gives way to woodland and shrubland, that means less rangeland for cattle. So from their point of view, this green glacier is literally removing billions of pounds of grass from the ranching industry. In terms of ecological implications of prairie wildlife, they’re losing their habitat.

And at Kansas State University, they’re seeing that prairie streams are drying up because the trees and shrubs create so many cracks in this very special, rocky ground beneath the tallgrass prairie. So the rainwater seeps too deep here in the Flint Hills of Kansas and just disappears.

And then, finally, we’ve got to mention the wildfires. Wildfires are getting worse. When you have drought and wind and things conspiring so that all these woody plants, these juniper forests, do finally go up in flames, we’re seeing really intense, catastrophic wildfires now in the center of the country. And just to give you an idea of how difficult it is to fight these fires, the University of Nebraska says that you can have flames that are 90 feet tall when you’re dealing with these thick Juniper forests compared to under 15 feet tall when it was healthy prairie that wasn’t infested with these trees.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I can definitely understand why people are trying to cut back the trees in these grasslands. But who’s doing this work? Who’s leading this effort?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Well, ranchers are doing a lot of it. Again, grassland is their livelihood. But it’s a really daunting task. I spoke with Daniel Mushrush about this. He’s a third-generation rancher. And he just kind of guesstimated that he and his family have probably killed maybe around 10,000 trees just in the past three years. And they are nowhere near done. But they’re trying to manage 15,000 acres of tallgrass prairie, which is an especially threatened kind of prairie. And that’s why Daniel Mushrush thinks people should really pay attention to this and get on board with preserving it.

DANIEL MUSHRUSH: If a coral reef is worth saving, if some pristine mountain stream is worth saving, then so are the Flint Hills. I think that’s the message I want to send is just that it’s not easy work, but it’s worthy work. At least we have a roadmap forward.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Are these ranchers getting any federal help to do this?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yes, they are. So that’s the roadmap that Daniel Mushrush was just referencing. So the Natural Resources Conservation Service launched a program. It’s called the Great Plains Grassland Initiative. And they’ve been rolling this out in Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota.

And this program brings expertise to landowners to help them figure out where to put their efforts, how to tackle these trees and shrubs really systematically, and also has the option of financial help to help them do this. It’s a real morale boost for people like Daniel Mushrush, who describe feeling overwhelmed by the situation.

And the idea is to preserve core areas where there will be relatively intact, large expanses of grassland into the future. And that’s important because– I mean, it’s important for ranchers, clearly, but it’s also important for wildlife that need these large expanses because small postage stamp remnants aren’t really enough to preserve this incredible biodiversity.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: And I imagine that a lot of the work to conserve the Great Plains prairies is actually cultural, helping people to just reframe the idea in their heads that trees are inherently good for the environment. Is that a big challenge?

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Yeah. So I would say we definitely have a pro-tree culture. But the reality is that trees harm certain ecosystems. Trees on the prairie are a point of tension in a lot of places because you may have ranchers who are desperately trying to hold on to their rangeland. And then nearby, you have landowners who welcome the trees and shrubs maybe. For example, they might not have a problem with transitioning to woodland because they’re hoping it will improve deer hunting, or they might want the privacy afforded by a treed landscape.

So even in grassland regions, opinions can be very fractured. And I think we’ve got to mention that this pro-tree culture runs really deep. Native Americans, as I referenced before, used to burn grassland regularly and very purposefully across much of this area to maintain rich hunting grounds and for other purposes. But then Europeans and their descendants came and, of course, killed and forcibly removed Native Americans from most of this grassland region.

The European Americans brought a different relationship to the land. There wasn’t anything like these vast grasslands in the countries that they or their grandparents had come from. So it was just obvious that it’s easier to build towns to live in the way that they were used to living if they would plant trees. That’s actually the origin of Arbor Day, Nebraskans planting a million trees in a single day, if you can imagine that, in the 1800s.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s so hard to imagine. That’s amazing.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: I really– a million trees, right? And then that tree planting ramped up after the Dust Bowl. So what it means is that we’ve been transforming the landscape for many decades now. You add in the extra CO2 in the air now, and it adds up, and it spells real trouble for the future of North American prairies.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s all the time we have for now. I’d like to thank my guest, Celia Llopis-Jepsen, host of the podcast Up From Dust from KCUR in Kansas city, Missouri. Thank you for joining us.

CELIA LLOPIS-JEPSEN: Thanks so much for your time.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.