A Clamp Down On Hurricane Dorian Data

6:35 minutes

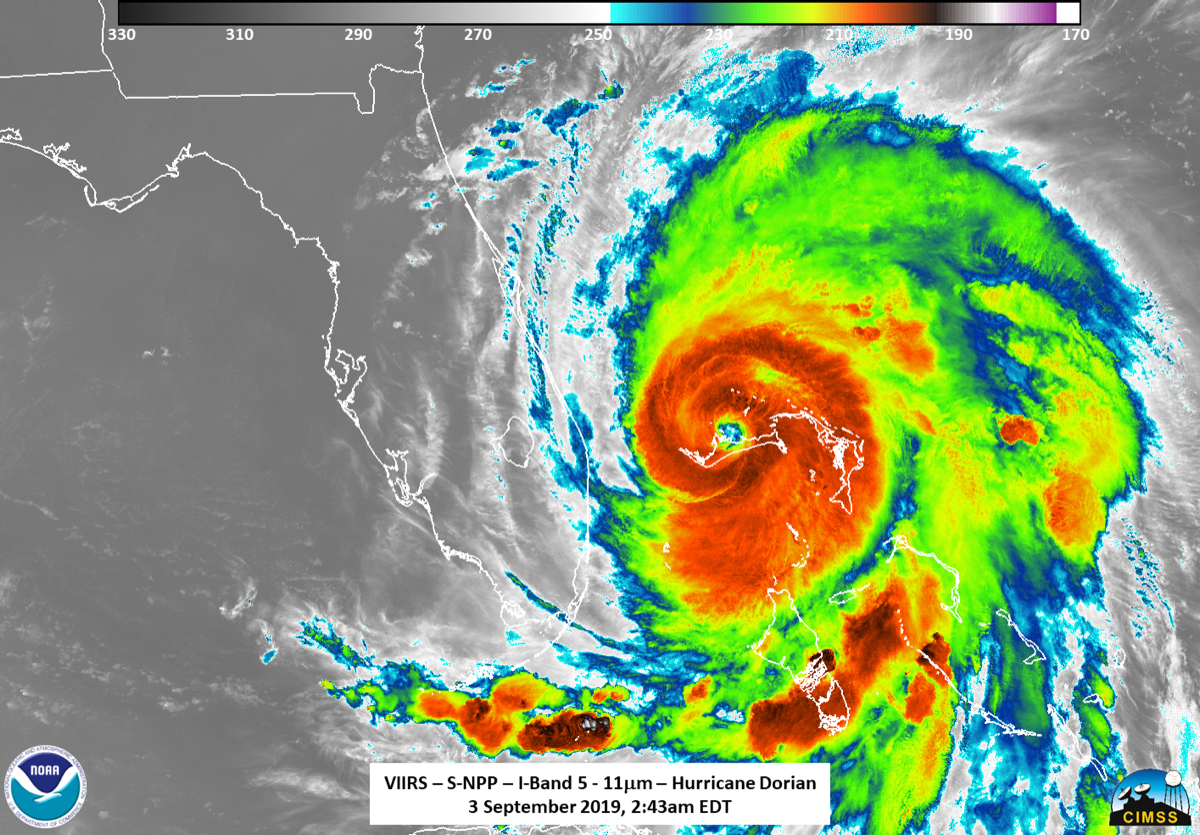

Two weeks ago, Hurricane Dorian slammed into the Bahamas as a Category 5 storm. The National Weather Service projection for the eastern coast of the United States contradicted claims in tweets from President Trump, in which he wrote that Alabama would likely be hit hard by the storm. A press release that was attributed to an unidentified NOAA spokesperson supported the president’s claims. Sophie Bushwick, technology editor at Scientific American, talks about this case of politics and science, a new blood test that could identify soldiers and individuals suffering from PTSD, and other short subjects in science.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Sophie Bushwick is senior news editor at New Scientist in New York, New York. Previously, she was a senior editor at Popular Science and technology editor at Scientific American.

This is Science Friday, I’m Ira Flatow. In the weeks following the National Weather Service contradicting President Trump’s prediction about the path of hurricane Dorian, also known as #sharpiegate, there have been reported threats or firings and suppression of science at the agency. Here to fill us in is Sophie Bushwick, technology editor at Scientific American. Welcome back, Sofie, always good to see you.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: So let’s talk about this. What happened in the weeks after Dorian? How has that administration and agency handled this?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Well the president and his support staff have doubled down on the idea that Alabama really was at risk from Hurricane Dorian, and then this was contradicted when the National Weather Service office in Birmingham tweeted that Alabama was in no danger. Which makes a lot of sense in terms of preparation, you don’t want people making runs on stores or thinking they have to evacuate if there’s no danger.

And then the New York Times has recently reported that the Secretary of Commerce then threatened NOAA– the National Weather Service is part of NOAA– and they threatened to fire the political appointees if they didn’t issue a corrective to the message. And so as a result, there was an unsigned memo that NOAA released, sort of saying that the Alabama office shouldn’t have tweeted out that Alabama wasn’t going to be in danger.

IRA FLATOW: So they were really asking politics to triumph over science in this case.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: That’s correct. And this really kind of points out the danger of a post-truth era, right. Like it’s one thing if you’re arguing about the size of a crowd, and it’s another thing when you’re talking about people’s lives at risk. I mean, knowing accurately where a hurricane is going to strike, and what areas are in danger, and which areas are not, is really vital to saving people’s lives and also to preventing damage.

And if you can’t rely on that, and if you so distrust of the Weather Service, that’s potentially extremely dangerous.

IRA FLATOW: And so, because for the next time, you may think it’s a hoax, also.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Exactly. Exactly. If you can’t trust an accurate hurricane forecast, then you’re not going to take action in the best possible way.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s move on to another story. Another interesting story about a test for PTSD.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yes. This one is really interesting, because there still, today, is a lot of stigma around post-traumatic stress disorder. Many people don’t, if they’re experiencing symptoms, they might not want to admit it or to go seek the treatment they need. So the military obviously has– a lot of soldiers are often exposed to traumatic situations, and they want to have some way of screening for PTSD that wouldn’t just rely on people self-reporting.

And so they’ve investigated. They supported research that has found a potential blood test that could be used to screen for PTSD. So basically, they chose about a million different biomarkers– so biomarkers are just things that could be like heart rate, or proteins, or molecules in the blood– and they compared these biomarkers in two groups of veterans. It was about 150 people, all of them had served overseas and had experienced a potentially traumatic event in battle.

And about half of them had symptoms of PTSD and the other half did not, so by comparing these biomarkers in the two groups, they narrowed down to a list of 28 different biomarkers. So 27 substances in the blood and heart rate, that could be used to differentiate between the groups.

IRA FLATOW: And was it pretty accurate in predicting?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It was. It was about as accurate as some other screenings. It was about 81% of the time it could distinguish between these groups when they tested it. And the idea is that this wouldn’t be– you wouldn’t just take this test and be like, oh, I have PTSD, but it would be, oh, this person potentially has PTSD. And it would allow that person to then go into a psychological evaluation or undergo further screening.

IRA FLATOW: It’s not quite ready, then, for prime-time.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: No, it’s not quite ready yet. First of all, they only tested it in a quite small group, right, like about 150 people initially. And then they tested it on a different smaller group. And the second thing is, it was only men in this group and it was only veterans. So if you wanted to use it in, say, the general population, or in women, you’d want to do a lot more testing. And indeed, the research group does plan to test it further.

IRA FLATOW: Interesting. Let’s move on to the Indian Space Organization, Space Research Organization, launched a lunar lander but they sort of lost contact with it, right? You know, it’s a sad story.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: It’s a little sad, but there’s a silver lining. So the lander was supposed to land, it would be the first lander to land near the south pole of the moon. And unfortunately, when it was about two kilometers above the surface, the Indian Space Research Organization lost contact with it and so they thought it might have crashed. But just recently– so this was a two-part mission, there was an orbiter as well as a lander– and the orbiter photographed a part of the surface of the moon. And the Indian Space Research Organization has said they found where the lander is and now they’re trying to re-establish contact.

IRA FLATOW: But the Indian program doesn’t get a lot of press here. They’re really very serious about space, aren’t they?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Yes, absolutely. They’ve sent an orbiter to Mars, they’re only the– they’ve landed a previous mission, they sent an orbiter around the moon and it crash landed at the end of its mission. And then this was their attempt at a soft landing. And if they’d achieved it, they would have only been the fourth nation to ever have a soft landing on the moon.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s keep our fingers crossed for reestablishing a connection.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: I will.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: Finally, your last story is shocking. I’m shocked because it’s about electric eels. Scientists found a new electric eel species?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So basically what happened was, we had just assumed that electric eels were all one species. And this study took about 107 different electric eels and they compared their head shapes and their DNA, and they say, no, there’s actually three different species we’re looking at here. And one of them, my favorite– electrophorous volti, I think, I might be getting the genus name wrong. But this species is the most shocking of all, it can release 860 volts in a shock.

IRA FLATOW: Wow!

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: For comparison, a defibrillator that can shock your heart back to life is about 1,000.

IRA FLATOW: Do we know why it’s so big, and how big it got that– why, you know?

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: So basically, the way that electric eels produce these shocks are with organs made up of electric current producing cells. And the idea is, if you have more cells they act kind of like batteries in a series and they can strengthen and increase the output of the shock.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting, Sophie. Thank you for taking time to be with us today. Always good to have you.

SOPHIE BUSHWICK: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Sophie Bushwick, a technology editor at Scientific American.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the host and executive producer of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.