An Artist Explores The History Of Humans Genetically Modifying Pigs

6:22 minutes

Over 100,000 people are waiting for organ donations in the United States. Many will likely never receive one, since there are so few available. So scientists are turning to pigs for potential alternatives. Their organs are remarkably similar to ours, and scientists are now using CRISPR to modify pigs’ DNA to improve transplantation outcomes. But although the field has shown major advances in the last decade, the technique isn’t ready yet. Recently, a patient who received a modified pig heart died six weeks after the surgery.

Artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg was intrigued by these recent advances, and looked into humanity’s history of modifying the pig over thousands of years for her new gallery exhibit, Hybrid: an Interspecies Opera. For the work, she interviewed scientists and archaeologists and even filmed in a lab that’s experimenting with genetically modifying pigs to create more human-compatible organs.

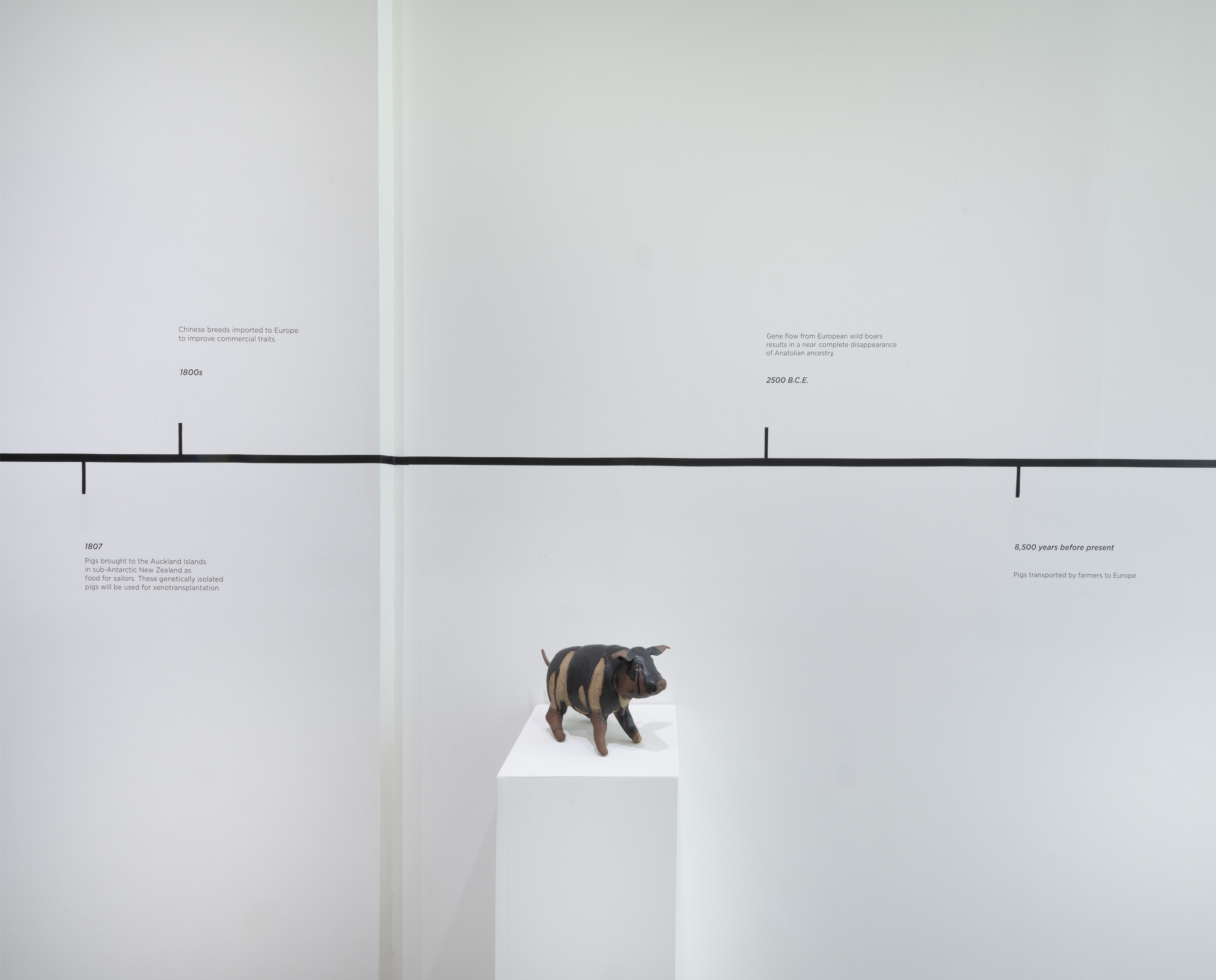

In the resulting documentary, which plays in the exhibit, the words from the scientists she interviewed are transposed into an opera composed by musician Bethany Barrett. Visitors can also find 3D-printed clay pig statues and a timeline of how humans have transformed pigs over ten millennia, thanks to selective breeding.

Dewey-Hagborg sat down with SciFri producer D. Peterschmidt to talk about how the exhibit came together, and how CRISPR could further transform pigs and our relationship to them.

Sign up to become an organ donor through the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

Hybrid: an Interspecies Opera is on view at the Fridman Gallery in New York City until December 13, 2023. The opera from the exhibit will be performed live at the Exploratorium in San Francisco in March 2024. Installation views, photos 1-3 / Stills from the film, photos 4-5. Images courtesy of the artist and Fridman Gallery.

Heather Dewey-Hagborg is an artist and biohacker based in New York, New York.

SPEAKER 1: To close out today’s show, Producer D. Peterschmidt is bringing us a story about an art exhibition that explores our relationship with pigs. D. is here to tell us about it. Hi, D.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: Hi, Flora.

SPEAKER 1: OK. Tell me about this show.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: Yeah. It’s called A Hybrid and Interspecies Opera, and it’s basically a multi-media ode to the pig. So there’s opera, there’s 3D clay prints of pig statues, and a short documentary of scientists who are working to create these compatible organs and pigs for human transplantation, which is called xenotransplantation. And basically, the show is just trying to get at humanity has had this millennia’s long relationship with pigs. We’ve been genetically modifying them for centuries just through breeding. And the show is kind of asking, how far will we actually go to make pigs work for us?

SPEAKER 1: Did the show make you see pigs in a new way?

D. PETERSCHMIDT: It did. I mean, it was really striking to see during the documentary the pigs actually in the lab and the scientists are very respectful towards them and clearly care about them. But ultimately, their lives are going to be used for research.

And so we think about pigs in the context of our food, but this kind of made me think about them in terms of how we’re trying to solve human health problems using them.

SPEAKER 1: Well, I can’t wait to hear more. D., take it away.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: In 2015, artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg came across news from the Wyss Institute at Harvard, which had made a record 62 edits to a pig’s genome, using CRISPR, to make their organs more compatible for human transplantation. More than 100,000 people are waiting for an organ donor in the US, and many of them will likely never get one. So since pig’s organs are so similar to humans, scientists have been genetically modifying them to make sure people can actually live a full life with, say, a pig heart.

SPEAKER 1: And I thought that was really fascinating on a philosophical level and, of course, all of the ethical questions that it raised.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: Heather also self-describes as a biohacker and has worked with genetics before in her art, and decided to pursue that topic for her next exhibit.

SPEAKER 1: So the main research question for me was really to probe this question that scientists very often say that genetic engineering is a continuation of 10 millennia, of domestication, selective breeding. And I wanted to just dig into that and see, is there– is it a rupture, is something radically new happening with CRISPR gene editing, or is it a continuation?

D. PETERSCHMIDT: You’re listening to Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

So she started doing research into xenotransplantation and interviewed scientists and archaeologists. And Heather was surprised how long we’ve been modifying pigs for our benefit. There’s a timeline on the wall in the exhibit that gives a highlight reel of our relationship over the last 10 millennia, how modern pigs were domesticated from ancient wild boars in both China and Europe.

Tissue and organ transplant experiments started in the 1900s. And in the last decade, scientists have been using CRISPR to reduce the chances of organ rejection from the immune system after surgery. But the field is moving so fast that she had to make a last minute change to that timeline.

SPEAKER 1: So as we were putting up the story of the last individual who received a transplanted heart, it originally said that the individual would still be living and he passed away, basically, the day before the opening of the art exhibit. So that was a sad change that we had to make.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: That patient, who was the second person to receive a genetically modified pig heart, died six weeks after surgery. Heather didn’t want to talk to just scientists over Zoom about xenotransplantation. She wanted to actually see one of these labs for herself.

So she went to the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, which has its own lab that is working on genetically modifying pigs for xenotransplantation, and she brought a film crew. The resulting documentary plays in the exhibit, but she took a slightly different approach to the soundtrack.

SPEAKER 1: And I was just really blown away by the power of the words of these people, the drama that was there, sometimes the humor. And so I started to– suddenly started hearing it in this kind of opera voice singing these words out. And then I thought, I wonder if I could make that happen– that would be a really interesting approach– and do something very different than your standard talking heads documentary.

And one of the really important points is what a tiny fraction the number of pigs being used for xenotransplantation would be relative to the number that would be used for meat production. And he says in there something like a few 100,000 per year, a fraction of the 3 billion consumed for food. And then, of course, the chorus that comes there, which is, thousands of clones every day.

[MUSIC PLAYING] –every day. Each pig will donate multiple organs, maybe helping a million people.

Luckily, I’m also not the one singing.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: Hey, that wasn’t that bad, though.

SPEAKER 1: But I do walk around with it stuck in my head.

(SINGING) There is a guilt. There is a betrayal.

D. PETERSCHMIDT: The film ends with Heather standing on a beach making a pit fire and placing 3D printed clay pig models that were scanned from ancient bore ceramic statues into the flames. It’s her way of memorializing pigs past, present, and future.

SPEAKER 2: When I started the research, I thought that seems pretty problematic to be exploiting all these pigs. And then through talking with scientists, eventually then meeting the pigs, meeting the veterinary scientists who were working with the pigs, seeing the care that was there in addition to, of course, the kind of tragic deaths that they face, definitely did give more dimension to my understandings of it.

But another branch of the project is around anticipating what pigs might become and thinking about directions that pigs might go in the future.

SPEAKER 1: Thank you, D.

That was producer D. Peterschmidt. You can check out Hybrid and Interspecies Opera at the Fridman Gallery in New York City for the next couple of weeks. And there will be a live performance of the opera at the Exploratorium in San Francisco in March.

You can learn more at our website, sciencefriday.com/pigart.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

D. Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.

Flora Lichtman was the host of the podcast Every Little Thing. She’s a former Science Friday multimedia producer.