Imagine you’re walking through the airport on your way to a flight. You’re navigating with your luggage, taking a leisurely stroll to your gate, when you suddenly come across an odd-looking, six-foot tall, refrigerator-sized box. As you approach, you realize it contains an entire museum’s worth of information about mollusks. Amanda Schochet, a computational ecologist, who makes such museums, hopes that this scenario becomes much more common in the future.

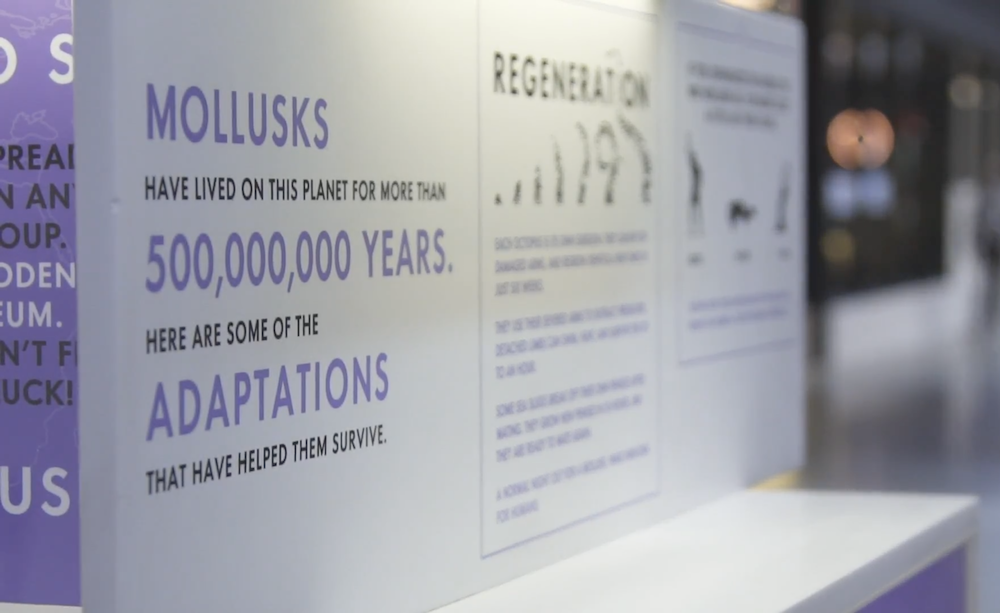

“The museum lures people in by being unexpected,” said Amanda, the co-founder of MICRO, a company that produces tiny museums. The Smallest Mollusk Museum, their first project, has 15 small exhibits crammed onto the four faces. “We have very carefully made it possible that you can approach it from all sides. We put a lot of thought into how to make the object feel like an addition to the room, to feel like a beautiful thing.”

By shrinking an entire museum like this, Amanda hopes that these tiny museums can go in all sorts of public areas, like shopping malls, waiting rooms, parks, and yes, airports. “The goal is to reach people where they already are, to integrate science and learning into people’s day-to-day [lives].”

Besides the pun potential, Amanda started MICRO because museums are not always the most accessible—for example, they tend to cluster in wealthier neighborhoods. “Traditional museums are amazing to visit, but they could reach a more diverse audience,” said Amanda. “If it’s hard to get to a museum, then you might not go. If it feels unwelcoming, then you might not go. Maybe you don’t know if you care about science, so you don’t want to spend 20 bucks and a whole day.”

So, what’s in this miniature museum? One exhibit examines the brains and intelligence of these animals. Since octopus intelligence is so unique, Amanda hopes the exhibit can inspire others to think about alien intelligence. “Mollusks are as different from us as we can possibly imagine. Some clams who don’t even have a brain at all and yet they’re still able to function. We want people to fall in love with them and realize that when you think about caring for the world, you should think about the classically ugly animals as well.”

MICRO plans on releasing a less pun-worthy version of their concept called the Perpetual Motion Museum, which will focus on physics and engineering. It all fits into what Amanda feels is important about museums. “The museum is really the place where you get to explore,” she says. “It shouldn’t just be for scientists to get to look through that perspective.”

“I feel very lucky that I got to study science in school and that I got to work as a scientist. And I really wanted to share that with people.”

Video Transcript

AMANDA SCHOCHET: The museum lures people in by being unexpected. We have very carefully made it possible that you can approach it from all sides. We do put a lot of thought into how to make the object itself feel like an addition to the room, to feel like a beautiful thing.

We can design this in a different way to just make it informative and inexpensive to produce but it wouldn’t give people that sense of wonder.

I’m Amanda Schochet and I co-founded MICRO, which is creating a fleet of six foot tall science museums that can go anywhere. We have 15 exhibits packed into this six foot tall box.

By shrinking this information down into boxes that can go everywhere, replicating the boxes and putting them out into shopping malls, hospital waiting rooms, airports, all these transit hubs, we’re getting them into into people’s spaces, welcoming people in. We wanted to feel like a human-scale experience.

Traditional museums, they’re amazing to visit, but they could reach more people and they could reach a more diverse audience. Museums are geographically clustered, especially in wealthier neighborhoods. If it’s hard to get to a museum, then you might not go. If it feels unwelcoming, then you might not go. Maybe you don’t know if you care about science or not, so you don’t want to spend 20 bucks and a whole day. There’s a lot of reasons that people won’t go to a museum.

At micro, the goal is really to reach people where they already are, to integrate science to integrate learning into people’s day-to-day. The reason that we first thought up mollusks was actually because I misheard my partner, Charles, who said he was going to the “smallest museum” and I heard the “mollusk museum” and I was really excited to go to that museum. Turns out, that’s not where he was going, but the idea stuck.

We have a brains exhibit where we get to learn the different ways that mollusks think. Octopus intelligence is a really interesting way to learn about potential forms of alien intelligence because it’s so different than how we think. We learn about clams who don’t even have a brain at all and yet they’re still able to function.

A big challenge of making these museums is just figuring out what to not include. We open up these amazing topics. There are a million things we could have written about mollusks and put into this museum. For every species of mollusks and there’s hundreds of thousands of them, there are infinite amazing stories. We choose what to include in the museum’s based on our narrative.

We add a lot of way-finding so you have a discrete start and an end. There’s exhibits in the middle that show different levels of detail. So there’s the bigger picture exhibits that kind of tell the whole story. There’s the more detailed exhibits that show you a little glimpse of how this works.

Mollusks are as different from us as we can possibly imagine an animal to be. We want to get people to fall in love with them and to realize that when you think about caring for the world, you should think about the classically ugly animals as well.

We learned the process of how to design a micro museum, as we design the smallest mollusk museum. And now that’s out in the world. Soon, we’ll be releasing our second museum, the perpetual motion museum, which is about physics and engineering.

In terms of how that is then built, in the case of the MICRO museums, every topic ends up having its own distinct building that house is it. And once it’s designed, it’s quite easy for us to replicate each one as demand requires.

I feel very lucky that I got to study science in school and that I got to work as a scientist. And I really wanted to share that with people. How does life work? How do we think? Wow do we interact with the world? AtMICRO, the museum is really the place where you get to explore. It shouldn’t just be for scientists to get to look through that perspective.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Credits

Produced by Luke Groskin

Edited by Sarah Galloway

Music by Audio Network

Additional Footage Provided by People’s Television and Science Sandbox, an initiative of the Simons Foundation

Special Thanks to Charles Philipp, Ruby Murray, and Amanda Schochet

Meet the Producers and Host

About Luke Groskin

@lgroskinLuke Groskin is Science Friday’s video producer. He’s on a mission to make you love spiders and other odd creatures.

About D. Peterschmidt

@dpeterschmidtD. Peterschmidt is a producer, host of the podcast Universe of Art, and composes music for Science Friday’s podcasts. Their D&D character is a clumsy bard named Chip Chap Chopman.