A Celebration of the Life in Flight Around Your Porch Light

16:44 minutes

Moths play a vital role in our ecosystems, but many people know little about them. That’s why Elena Tartaglia, an ecologist at Bergen Community College in Paramus, New Jersey, thought it was time to raise awareness.

After Tartaglia had the experience of going mothing in East Brunswick, she decided to try and start a regular summer mothing night. What’s mothing? Just going outside to find and record moths.

“We thought, wouldn’t it be fun to get everyone in New Jersey to do a moth night?” Tartaglia says. “And then, as the night progressed, we just thought, wouldn’t it be fun to get the whole US? And then we thought, why not get the world? And we put it on social media and we had interest all over the place, surprisingly. And now we have events — I think we have over 450 events in the 42 countries this year.”

For those who have never tried mothing, Tartaglia says it’s not difficult.

“Mothing is really easy. You need no special equipment,” Tartaglia says. “All you have to do is set out a light, or turn on your porch light and then wait for them to come. And if you don’t feel like sitting out all night, you can leave the light on all night and come out in the morning and you’ll see what you got.”

Moths, according to Tartaglia are often misunderstood. Taxonomically, they’re not that different from butterflies, but she says there are ways to tell them apart.

“The easiest thing to do is to look at the antennae,” Tartaglia says. “Butterflies have a little spoon-shaped antennae, kind of executed on the end. And moth antennae are pretty variable. Some of them have straight antennae and a lot of the males of many species have these beautiful, long, feathery antennae… The other almost foolproof method is that … every butterfly is out during the day. There are no night time butterflies.”

Moths are more important to our ecosystems than many people realize.

“They act as pollinators, so they aid in plant reproduction,” Tartaglia says. “Bees are great pollinators, other insects are great pollinators. But moths don’t actually return to a nest at night, so they have the potential to carry pollen pretty far distances, which is really good for plant genetics because it can outcross a little farther. And additionally, moths are important parts of food webs — they provide food for birds, for bats, as well as some mammals.”

According to Tartaglia, some moth species are facing population declines, something she says is likely due to habitat loss. There are many who see moths as pests. For those people, Tartaglia offers some perspective.

“There are between 150 and 5000 species of moths in the world,” Tartaglia says. “There are a couple that are pests, and unfortunately those are the ones we interact with a lot, but the vast majority of moths are just neither helping nor harming humans and they don’t care about us. We don’t care about them. And then of course there are the beneficial ones — the pollinators, the ones that play important roles in food webs, the ones that we’re modeling microaerial vehicle flight after.”

For those who are just trying to protect their wool coats from moths? Tartaglia has some advice.

“You can get rid of them by putting your clothes in the freezer if you have a moth infestation problem.”

Elena Tartaglia is co-founder of National Moth Week and an ecologist at Bergen Community College in Paramus, New Jersey.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky sitting in for Ira Flatow.

I know you’ve had your calendar marked for quite some time. The cake has been ordered, the decorations hung. The porch light has been lit for your annual Moth Week Celebration. We’re in the middle of the fifth annual National Moth Week, and here to guide us in our celebration is one of the co-founders of the National Moth Week Observance. Elena Tartaglia is assistant professor of biology at Bergen Community College in Paramus, New Jersey. Welcome back to the show, and happy Moth Week to you.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Thanks, John.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m really glad you’re here. We’ve got a lot of moth questions, and if you have a question for us, 844-724-8255– that’s 844-SCITALK– maybe if you have a favorite moth or if you’re a moth aficionado. A question I’m sure you get a lot is what’s the difference between a moth and a butterfly?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: That’s a great question and one that I really never get tired of answering. From a taxonomic perspective, there really isn’t a difference. This just speaks to our need as humans to classify things as either/or.

But there are a couple differences. If you’re looking at an insect, and you really need to know is this a moth or a butterfly, the easiest thing to do is to look at the antennae. Butterflies have a little spoon-shaped antennae. Kind of looks like a Q-tip on the end.

And moth antennae are pretty variable. Some of them have straight antennae, and a lot of the males of many species have these beautiful, long, feathery antennae. So, that’s one of the easiest ways to tell.

And then the other, almost foolproof method is that butterflies are all diurnal, so butterfly is out during the day. There’s no nighttime butterflies. So if you’re looking at a lepidopteran in the daytime, it’s probably a butterfly. There are a few moth species in the day. And if you’re looking look a lepidopteran at night, you know it’s a moth.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Ah, OK. You love moths. A lot of people, yeah, I can take moths or leave moths. So, give us a pep talk about moths. Why should we care about them so much?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Well, moths are really important in ecosystems. Number one, they act as pollinators, so they aid in plant reproduction. And especially in the American Southwest, they’re a very important suite of pollinators there.

And they actually can carry pollen for very far distances. Bees are great pollinators. Other insects are great pollinators. Moths don’t actually return to a nest at night, so they have the potential to carry pollen pretty far distances, which is really good for plant genetics because it can outcross the little farther.

And additionally, moths are important parts of food webs. So, they provide food for birds, for bats, as well as some mammals in addition.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You’re talking about them and their role as pollinators. We’ve been worried about the bees and bee colonies. We’ve been worried about monarch butterflies, whether or not they’re getting enough food to make their migrations. Do we have worries about moths right now?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah. Unfortunately, we do see declines in some species. Moths aren’t quite as well-studied, and that is one of the goals of National Moth Week, is to look at moth populations. They’re not as well studied, but we are seeing declines in some species of moths, unfortunately, and a lot of that is down to, with a lot of conservation, you see habitat loss as the main factor in declines.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Why did you start studying moths?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: That’s also a really great question. I was working on my dissertation, and I wanted to study pollination in urban environments. And when you do a dissertation, you have to carve out your own little, special niche, and not very many people in my area were studying that. I saw a professor give a talk on moth pollination, and I was fascinated, and so, I started to look into moth abundance and diversity in pollination in urban environments, in New York and New Jersey.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And it hooked you?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: It really did. And so, I started going to these moth nights in East Brunswick, and that’s how Moth Week actually got started. Just a couple of us going mothing in East Brunswick, and we thought wouldn’t it be fun to get everyone in New Jersey to do a moth night? And then as the night progressed, we just thought wouldn’t it be fun to get the whole US?

And then we thought why not get the world? And we put it on social media, and we had interest all over the place, surprisingly. And now, we have events. I think we have over 450 events in 42 countries this year.

JOHN DANKOSKY: How do you go mothing? What does mothing consist of?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Mothing is really easy. You need no special equipment. You can get special equipment, but all you need to do is set out a light. Now, I have a really strong, full spectrum mercury vapor bulb, but if you have ever come home late at night, you know that moths will fly to any porch light. So, all you have to do is set out a light or turn on your porch light and then wait for them to come.

And if you don’t feel like sitting out all night, you can leave the light on all night, and come out in the morning and you’ll see what you got.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You know what my next question is, though. Why did they go to the light? Why are they always flickering around the light whenever I come home at night?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah, so that’s another question that as scientists we can ask a moth why it’s flying to a light. We have the best hypothesis is that moths, and other nocturnal creatures, actually navigate by guiding themselves to the brightest object in the night sky.

Now normally, that’s the moon, but when an entomologist puts out a moth light, that automatically now becomes the brightest object in the sky, and moths will navigate towards that. Now of course, it’s not the moon, so once they get there, they’re kind of dazzled by that bright light, and they go into their torpor, their sleep mode.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want you to a call here. Daniel is calling from Tacoma Park, Maryland. Hi, Daniel. What’s your question?

DANIEL: Every time you watch a cartoon, and you see a cartoon that’s basically opening their closet, you see like the moths fly out, and they always go after the clothing. So, why do moths eat clothing, and what is about it that attracts them to that?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Thank you very much for the question. OK, do moths eat clothing, first of all, or is this a cartoon fantasy?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: No, they do, just a couple of them. So, not every moth and not even most moths. Just a couple of moths will eat clothing. And they’re attracted to the natural fibers, so they’re eating your wool sweaters and sometimes silks as well. They’re attracted to the natural fibers, and you can get rid of them by putting your clothes in the freezer if you have a moth infestation problem.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Hold it. Putting your clothes in the freezer?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah, that’ll kill them.

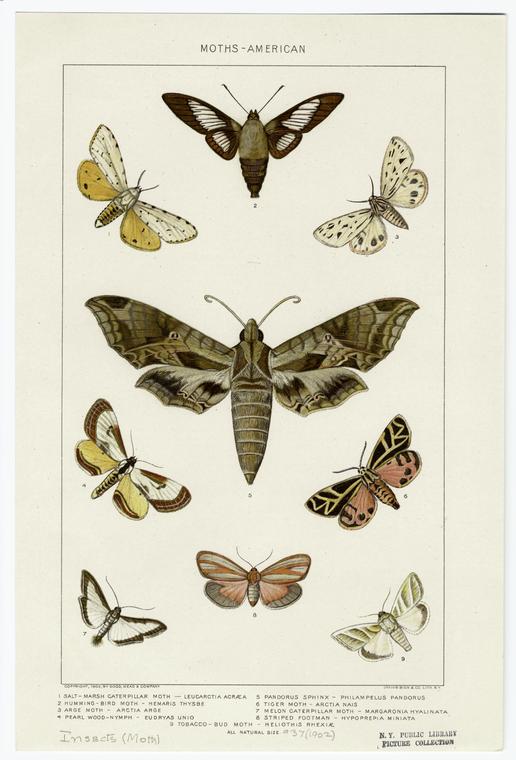

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK. So, I don’t know if I put all my clothes in the freezer, if they’d all fit in there. I want to talk about some of the moths that you brought in for us, and you had a beautiful display here. I know that you selected one type of moth for special attention this year. Maybe you could to point this out to me. What do you have?

JOHN DANKOSKY: We are doing the underwings this year. For the past few years of National Moth Week, we’ve been highlighting a certain group, and this year we chose the underwings. Most underwings are in this genus called Catocala, which actually in Greek means “beautiful underwing.”

And they are cryptic on the top. So, when they’re wings are folded, they blend in with bark. And then when they are startled by a predator, their defense is to open their forewings, and their hindwings have these beautiful bright colors on them. And so, the best hypothesis we have is that that is to startle away their predators, which are some nocturnal birds.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh, interesting. So that’s what the underwings are, and you can see them there. One of things always fascinated me about moths is sometimes the camouflage, sometimes the gigantic eyes that you’ll see that will make it look like it’s a bird or something else. What are some of the more amazing moth species that do something that we just probably couldn’t have thought up ourselves? I mean, they do have some fairly unique patterns.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah. A couple of the other species that we actually have in this area, in the New York, New Jersey area, one of them is the Io moth. That one has the best eye spots to my knowledge.

So yeah, they can do that startle defense, and they can look like the predators of their predators. And so, once they open their wings, their predator is startled because they think they’re about to get eaten, perhaps.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Ah, OK. I got another call here. John is in Kingsport, Tennessee. Let’s get to John. Hi, there. You’re on Science Friday.

JOHN: How are you doing today?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Doing well. What’s on your mind?

JOHN: I’m having an invasion problem with pantry moths, and they seem to be able to get into anything that’s not glass or something. Is there any material that cannot chew through, and how can you get rid of those little, pesky bugs?

JOHN DANKOSKY: John, thank you very much for the phone call. A couple of moth hating calls so far, Elena. You seem disappointed by this, but this is a problem. I’ve had pantry moths before, too, so what can you tell John?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: That’s OK, I’ve also had pantry moths. You’re doing the right thing by keeping your grains in glass because they can’t get through that, and they can’t get through hard plastic. So, as soon as you get your grains, do you take them, and put them into your nice looking glass containers, which look better in your pantry, anyway.

And again, if you have problems with moths coming in in the grains, you can store them in the freezer for a little bit, and that should take care of the problem. Unfortunately, if you already have a bad infestation, it might be time to start over your little grain pantry.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Yeah, and they really are hard to get rid of. I mean, are moths considered a pest species? I know there’s just so many different types of them. When they chew through your clothes and your closet, or they eat your grains in your pantry, they are, but are they considered, classified a pest species in any places?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Well, you know, there’s between 150,000 and 500,000 species of moth in the world.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So, that’s a few.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah. So, there are a couple that are pests, and unfortunately, those are the ones we interact with a lot, but the vast majority of moths just neither help nor harm humans. And they don’t care about us, we don’t care about them.

And then, of course, there are the beneficial ones, as I just mentioned. The pollinator is the ones that play important roles in food webs, the ones that we’re modeling micro-aerial vehicle flight after, as well. Some of them can fly amazingly fast and very agile, and there are these tiny, little micro-aerial vehicles, we call them, that are modeled after the flight of some of these moths.

JOHN DANKOSKY: That’s really interesting. You know, I mentioned the monarch butterflies and their long migration. Do any moth species do something like this, long migrations over long distances?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah, so moths actually can migrate long distances. I don’t actually know the exact figures on that. And some of them can fly up to a couple of kilometers in one night. So, a lot of them are quite long distance fliers.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And if you have questions, 844-724-8255. 334 That’s 844-SCITALK. Questions about moths or perhaps favorite moths.

In this display that you brought me, there’s one in the upper right hand corner here. It’s gigantic. It’s probably not even the biggest moth that you’ve seen, but what exactly is that? Maybe you can describe it for us and tell us what kind of moth that is.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: That’s a promethea moth, and that’s in the family called the Saturniidae, the giant silkworm moths. And those are amazing because, obviously, they’re beautiful to look at. And another weird fact about them is that as adults, those moths don’t even have a mouth. They don’t eat at all. All the nutrition that they take in, they take in their larval or caterpillar stage. So, when people are always like, oh, moths chew through clothes, these can’t even do that.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m confused by this, and I wanted to ask you about this. I’ve heard about a few different types of moth species that don’t have mouths. It comes out of being a caterpillar. It’s a moth now, but it doesn’t have a mouth. It can’t take in any of its own nutrition?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: No, that’s true. And I think the trick is not to separate in your mind so much the larval stage from the adult stage. Just like you or I can store fat in our bodies, moths can do that as well. And so as adults, they just have stored fat left over from that larval stage.

And you know, they don’t live very long. Those are some of the shortest lived moths. I think their max lifespan is probably about 10 days.

JOHN DANKOSKY: OK. How long is a very long lifespan for a moth species?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Probably a couple of months. And I mean, even in the tropics where they have warm weather, because cold is a limiting factor for them up here, but even in the tropics where they have warm weather, they would have more broods per season, so more life cycles per season, rather than longer lives.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, and we’re talking about moths and Moth Week with Elena Tartaglia. She’s assistant professor of biology at Bergen Community College in Paramus, New Jersey. She’s co-founder of National Moth Week. You might not have known it was National Moth Week, but it is, so we’re celebrating with her.

Let’s go to Carol who’s calling from Old Lyme, Connecticut. Hi there, Carol.

CAROL: Hi how are you doing?

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m doing well. What’s on your mind?

CAROL: We have this new visitor to our yard, and we looked it up online. It’s called the hummingbird moth. We had never seen anything like it. We thought it was a baby hummingbird at first, but we noticed it had a antennae and more than two legs. Why are these so different in body shapes and other types of morphology, like their wings, than other types of moths that you see?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Great question. Elena?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: I love this question. Thank you. I actually studied this type of moth for my graduate research, and these moths are mimics. The one that you saw, it was in the genus Hemaris, and some of those are mimics of hummingbirds, as you saw, and some of them are mimics of bumblebees.

And so, they kind of look a little bit like both. And these moths are some of the few diurnal or daytime moths, so they are acting as mimics. And they’re protecting themselves from their predators that are mainly birds. And so, in looking like the humming bird, most birds probably won’t eat a humming bird, and then the ones that look like bees are actually mimicking something that can sting. And so, in looking like bees or birds, they’re actually protecting themselves from the fact that there are more predators of them out in the daytime.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You mentioned some of the camouflaging techniques or the ways in which moths can pretend to be a predator. What are some of the defense mechanisms that they have? Because there’s a lot of predators out there. I’m sure a lot of birds and other things want to eat them. What are some of the really cool defense mechanisms?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Well, some of them are distasteful, just like monarch butterflies are. If they’ve got bright colors, many of them do have chemicals in their bodies that make them taste bad. And a lot of the caterpillars will defend themselves by, again, mimicking snakes or by having postures that are just sort of threatening to birds or other predators.

JOHN DANKOSKY: If I wanted to attract moths into my yard, you can talk about different sorts of gardens where you’d attract butterflies. Is it the same sort of thing? Are other types of plant species or other things that you would put in your yard to try to get more moths, if indeed that’s what you wanted?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Sure. Moths have a proboscis just like a butterfly does, that straw-like mouth part, and so, you want to look for flowers that have a tubular shape that they can drink from. And in addition, since moths are mostly out at night, you want to look for flowers that are open at night, and producing nectar at night, and are white or light colored so that the moths can see them. Additionally, moth flowers often have a very strong scent to them because moths have a very strong olfactory system. So, look for flowers like that, and you should be able to attract moths.

And another way that you could attract moths without plants– this is pretty cool, people like this– is that you could mix up some old beer and rotten fruit that you have hanging around and let it ferment for a few days. And then you can paint it on some of your trees, and that will also attract moths as well.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Old beer and rotten fruit.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Yeah.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I got to say, that doesn’t sound as much fun as having a nice garden. I mean, truly, that’s not necessarily something I’m going to do. Let’s go to a call in Denver, Colorado. Reeves is there. Hi, Reeves.

REEVES: Hi.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Hi. You’re on the air. What’s your question?

REEVES: Great. When I was a young man, I remember there was this huge moth population. They just sort of surge. You go to open up your screen door, and like a thousand moths just sort of fly out. And I remember every morning, my dad would go downstairs, and there were so many moths in the house, just he’s standing there vacuuming them out of the air. Which is probably poor form for Moth Week, but my big question is why do we have these huge surges in moth populations every once in a while?

JOHN DANKOSKY: You know, it’s a good question. I was telling our director, Charles, before the show, I actually had an experience like this once where I saw just thousands of moths at one time, and then they were all gone by the morning. What happens there? Why does that happen?

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Well, that’s another great question. Many insect populations, moths included, have what we call boom and bust population cycles. And so, some years you get a big boom, and some years you get very few. And I’m not an expert on this. It’s probably dependent on either just random cues, or it may be some environmental cues that signal them to have a boom population one year.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, I want to thank Elena Tartaglia, who is assistant professor of biology at Bergen Community College in Paramus, New Jersey, co-founder of National Moth Week. If you’d like a how-to guide on collecting moths, head on over to sciencefriday.com/moth. Happy Moth Week. Thanks for coming in.

ELENA TARTAGLIA: Thanks for having me.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.