A Tale Of Two Glassworkers And Their Marine Marvels

Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka are perhaps best known for crafting a collection of glass flowers for Harvard. But together they made their mark fashioning thousands of marine invertebrate models.

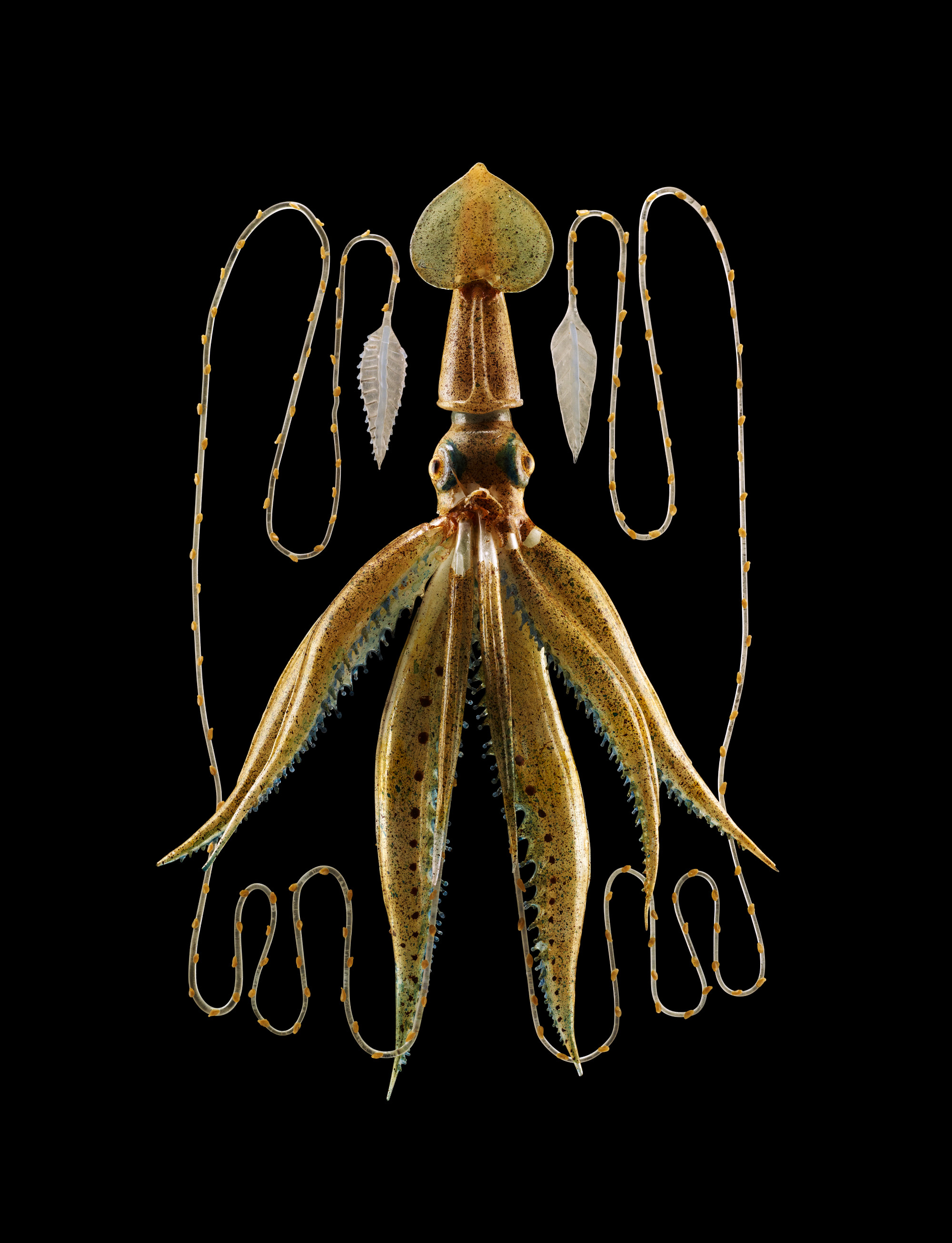

This common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) is from Cornell’s extensive collection of glass marine models fashioned by Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka. Photo by Gary Hodges

This octopus may evoke the spirit of life, but it never swam the ocean depths. It’s made of glass.

The specimen is one of thousands of meticulously detailed marine invertebrate models fashioned between 1863 and 1890 by a father-son glassworking duo, for the primary purpose of research and education. Collectively, their work depicts more than 700 different species—including various anemones, squids, and sea stars—found in waters around the globe.

The models’ destinations were also far-flung. From their glassworking studio in Dresden, Germany, Leopold Blaschka and his son, Rudolf, shipped their fragile pieces to museums and academic institutions in locales as diverse as Australia, India, Japan, and the United States (where Cornell University now holds what’s likely the world’s largest collection, at more than 570 pieces).

“They’re extraordinary works of art, but the precision with which they’re made and their representational accuracy was there initially to convey scientific knowledge,” says Marvin Bolt, curator of science and technology at The Corning Museum of Glass, where a Blaschka exhibit called Fragile Legacy: The Marine Invertebrate Glass Models of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka opens on May 14. It features not only a medley of the Blaschkas’ models, but artifacts from their studio, too. (For more than 40 years, conservators at the museum have been steadily working to stabilize Cornell’s Blaschka collection so it endures for years to come.)

The Blasckhas deliberately focused on crafting models of soft-bodied organisms, because real-life specimens were prone to losing their shape and color when preserved in alcohol and were hard to study in detail. Their diaphanous medium was particularly fitting for their subject matter. “No other material [besides glass] can convey the translucency of soft-bodied animals equally well,” says Bolt.

Leopold and Rudolf descended from a long line of glassworkers and demonstrated the kind of skill that springs from inherent ability honed over time. “As a child, Rudolf would have seen his father, and Leopold would have seen his father, and so on and so forth,” says Bolt. “So they grew up with this—it was part of not just their DNA, but part of their experience.”

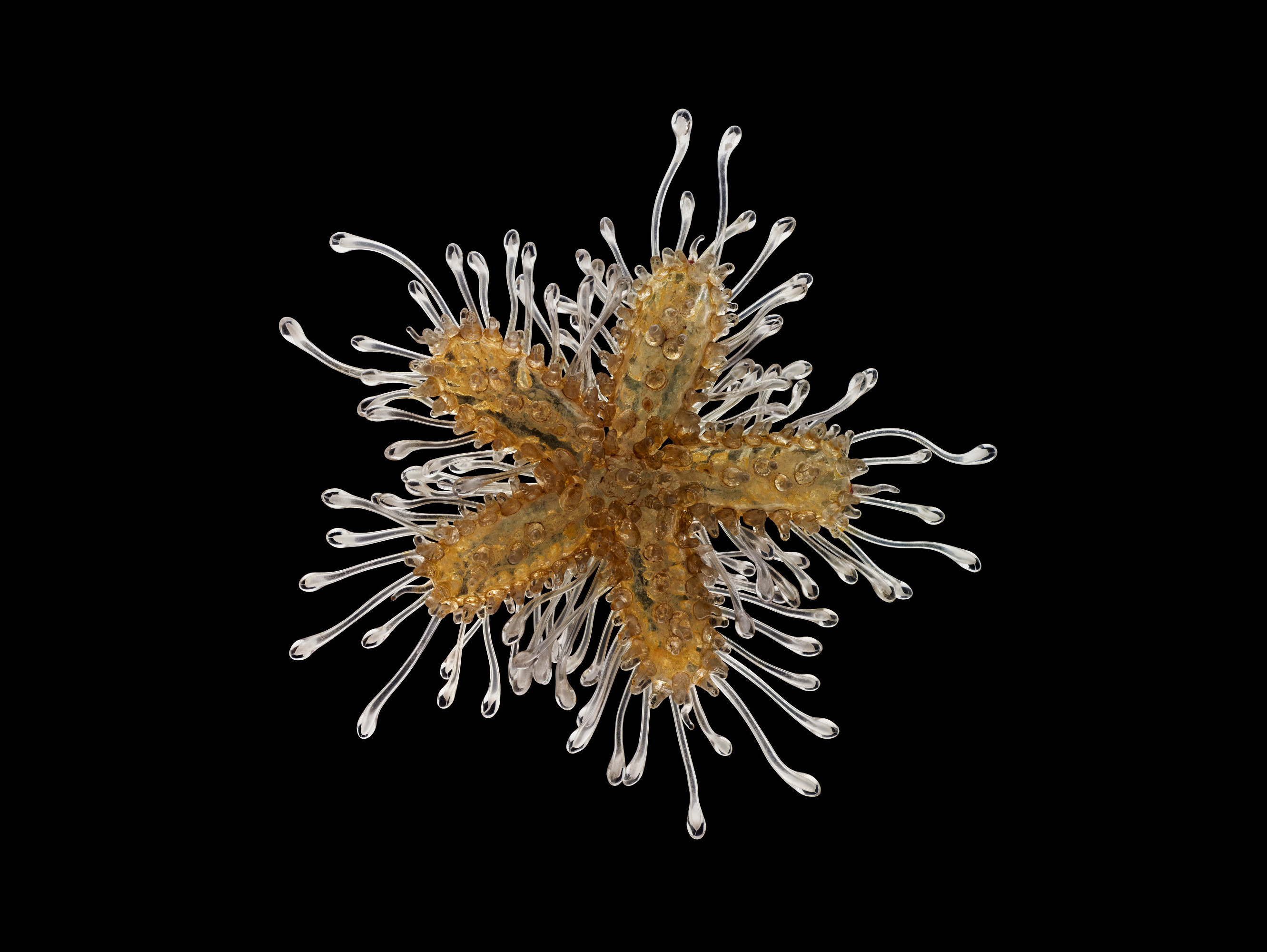

![The siphonophore Apolemia uvaria, in glass. This piece “must be the most stunning glass in our [Cornell] collection, both for it size, complexity, and sheer compositional brilliance,” writes Drew Harvell in A Sea of Glass. Photo by Kent Loeffler. Image file courtesy of A Sea of Glass, by Drew Harvell](http://www.sciencefriday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Harvell_3.4_siphonophores_resized.jpg)

Leopold, who was born in what’s now the Czech Republic, was first an apprentice goldsmith and gem cutter before he joined the family business making costume jewelry. Two tragedies—his first wife’s death, followed by his father’s—prompted a yearlong getaway to the United States in 1853 (he would marry again later and have Rudolf). One evening aboard ship, he had an epiphany after witnessing a sparkling display of bioluminescence enlivening the water.

“This was the moment he first imagined creating a bioluminescent jellyfish spun from glass,” marine biologist Drew Harvell writes in her new book, A Sea of Glass: Searching for the Blaschkas’ Fragile Legacy in an Ocean at Risk, which explores the natural history of the Blaschka models’ living counterparts, and the environmental perils they face.

Before Leopold tried his hand at animal models, however, he experimented with botanicals “for his own amusement,” according to an article by David Whitehouse, former chief curator of The Corning Museum of Glass. In the early 1860s, Leopold created a set of orchids and other plants for an amateur botanist and prince named Camille de Rohan, who had caught wind of his skills.

The commission was fortuitous. As Harvell recounts in her book, the prince introduced Leopold to Heinrich Gottlieb Ludwig Reichenbach, director of both the Dresden Botanical Gardens and the Dresden Natural History Museum, who ordered a series of sea anemone models to accompany an exhibit of lithographs on the subject, created by the naturalist Phillip Henry Gosse.

Squid models followed, helping form the underpinnings of a “glass tree of life, from which would sprout a full spineless menagerie: jellyfish, sea slugs, octopuses, worms, brittle stars, sea cucumbers, and sea squirts,” writes Harvell, who’s also the curator of Cornell’s Blaschka collection.

The Blaschaks, who moved to Dresden in 1963, worked from various source materials, including illustrations like Gosse’s and the work of zoologist Ernst Haeckel, as well as preserved specimens.

Some time around 1877, when Rudolf became a full-time partner, they began ordering live specimens from various suppliers, maintaining them in saltwater aquariums in the studio they shared. “They were perfectionists,” Harvell said in an interview. “They got to the point where they really felt they had to see the live animals and work directly from [them].”

The Blashkas also made their own paintings and illustrations “to get the pose, colors, and anatomy of each piece right before starting their work in glass,” Harvell explains in her book.

To render their models, Leopold and Rudolf relied on a technique historically known as lampworking, now called flameworking. “That basically implies using a flame to melt and shape glass rods or glass tubes,” says Alexandra Ruggiero, co-curator of The Corning Museum’s Blaschka exhibit. They fashioned each component separately and then assembled the parts using a variety of materials, including wire, metal, resin, paper, and adhesives, she says. For maximum verisimilitude, they painted their pieces with enamel (sometimes they used colored glass, too).

“They would do whatever it took to make sure that the model appeared as realistic as possible,” says Ruggiero.

In some cases, the Blaschkas created whole life stages in glass, from egg to larva to adult, for example. They even created enlarged versions of to-scale models in order to zoom in on details. “The students could handle them and look at them with their eyes rather than having to look through, say, a microscope or a magnifier,” says Bolt.

Of course, as with any new venture, the Blaschkas’ first models were “not particularly elegant,” says Bolt. But they eventually mastered their art. Later pieces are “really just breathtaking when you look at them and see the fine detail and the fine threads of glass, these tiny little filaments that they’ve created and then attached—and not just one or two of them, but, in some cases, dozens or even hundreds that are assembled together. It’s truly extraordinary,” he says.

So exceptional was the quality of their output that modern glassworkers would be hard-pressed to replicate it, according to Bolt. “You talk to people who are today experts in flameworking, and they’ll say, ‘Yeah, we know how they did it, but we can’t actually do this ourselves; we just don’t have the skill,’” he says.

The Blaschkas weren’t the only 19th-century craftsmen fashioning scientific models, according to Corning’s curators. But they cornered the market in glass models, working with buyers and agents who sold their pieces through catalogues. “These were the Bentleys, and other people were making Yugos,” says Bolt.

Eventually, after nearly 30 years devoted to modeling marine organisms, the Blaschkas shifted their attention back to botanicals when they met with an offer they couldn’t refuse: A Harvard botany professor offered a handsome commission for an exclusive collection of plant models, which became known as the “Glass Flowers.” The assembly, which is typically on display, consists of more than 4,000 pieces representing more than 830 species.

Today, the marine models are enduring examples of a successful union between science and art, and Harvell uses them as teaching aids at Cornell. For her, they’re a source of inspiration at a crucial time for ocean conservation. As she writes in A Sea of Glass, “My vision is that these masterpieces of glass art motivate wonder and appreciation for our ocean world.”

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Julie Leibach is a freelance science journalist and the former managing editor of online content for Science Friday.