Above the Ice, an Artist Goes Deep

Artist Justin Brice Guariglia will be collaborating with NASA in Greenland to explore how its icy landscape is changing.

In 2008, philosopher Timothy Morton invented the term “hyperobject” to describe things that are too vast in temporal and spatial terms for a human to fully comprehend. Think about all the Styrofoam that exists (and will forever exist) on earth, for example, or about how long one million years is. It’s difficult to wrap your mind around those concepts because you can’t experience them directly.

Artist Justin Brice Guariglia has been focusing on the idea of hyperobjects for a few years now. “These nebulous things I find fascinating,” he says. “How do you talk about it; how do you think about it?”

In particular, he’s fascinated by the scale of human influence on the global landscape, and by how he can represent that notion through immense, meditative pieces of artwork.

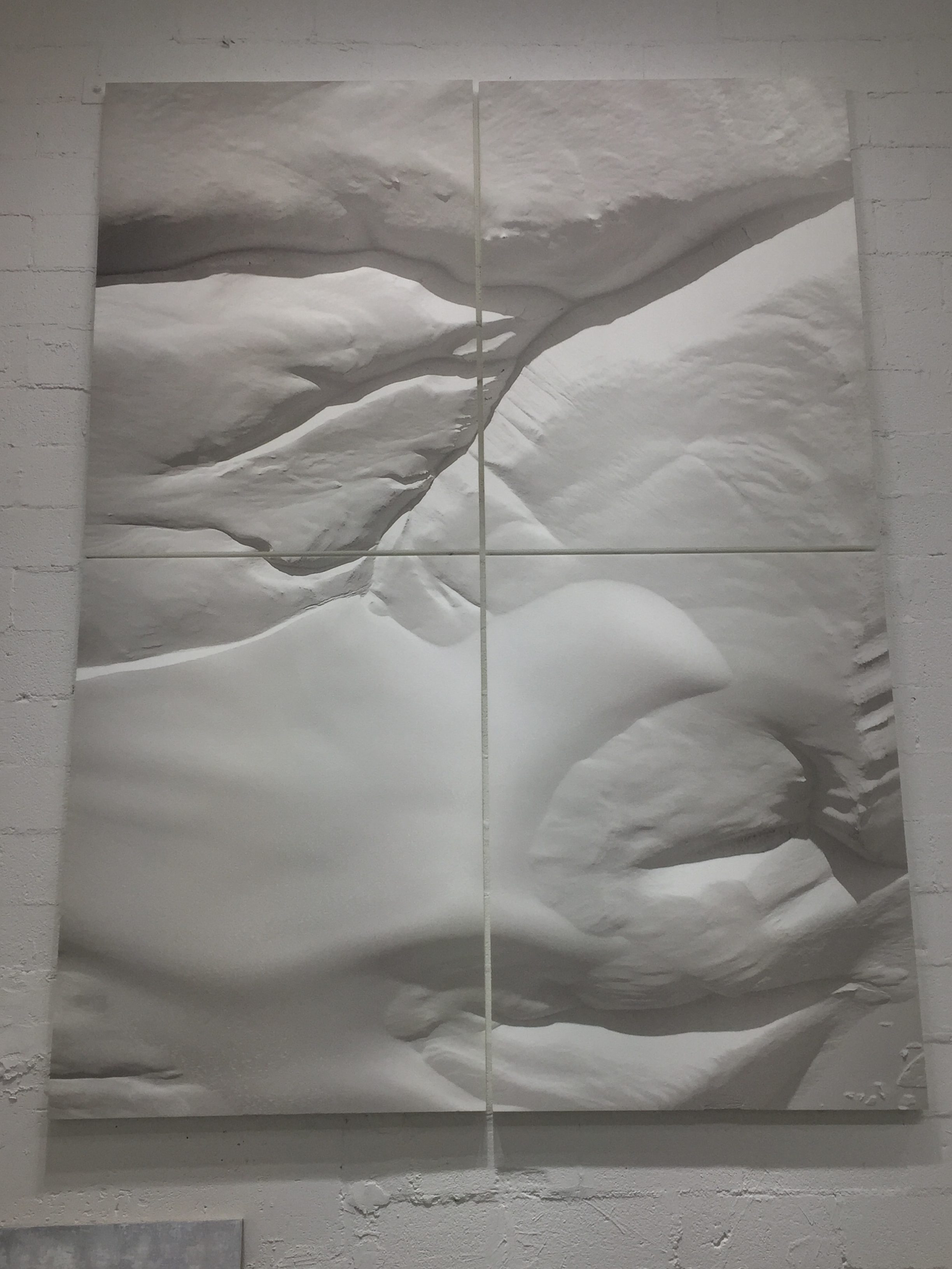

Take his piece APR 23, 2015 19:08:026 GMT, a 12 feet-by-16 feet photographic print that spans nine panels. Named after the date and time that he took the photograph, the piece depicts an ice mélange, which is a mixture of accumulated snow, sea ice, and icebergs that have calved from a glacier—in this case, the Jakobshavn glacier in Greenland.

Jakobshavn is a notorious fast-moving glacier. In the summer of 2012, for instance, it lost ice at an unprecedented rate of about 150 feet per day, according to a 2014 study. Pointing at the art piece in his Brooklyn-based studio, Guariglia says, “that’s 100,000-year-old ice. That’s gone. What you see in that picture is already melted.”

By preserving in art what’s changing in reality, he hopes viewers will contemplate environments that they might never have otherwise seen, or even known about.

“The concept of what’s happening to the ice is so complex—the ice is bearing the brunt of our activities,” Guariglia says. “As we burn a fossil fuel or consume energy, that has an impact and an effect all around the world. It accumulates as heat in the ocean and the atmosphere, and suddenly we have these ice sheets starting to transform and melt.” And “what happens there” in Greenland, for example, “impacts you here.”

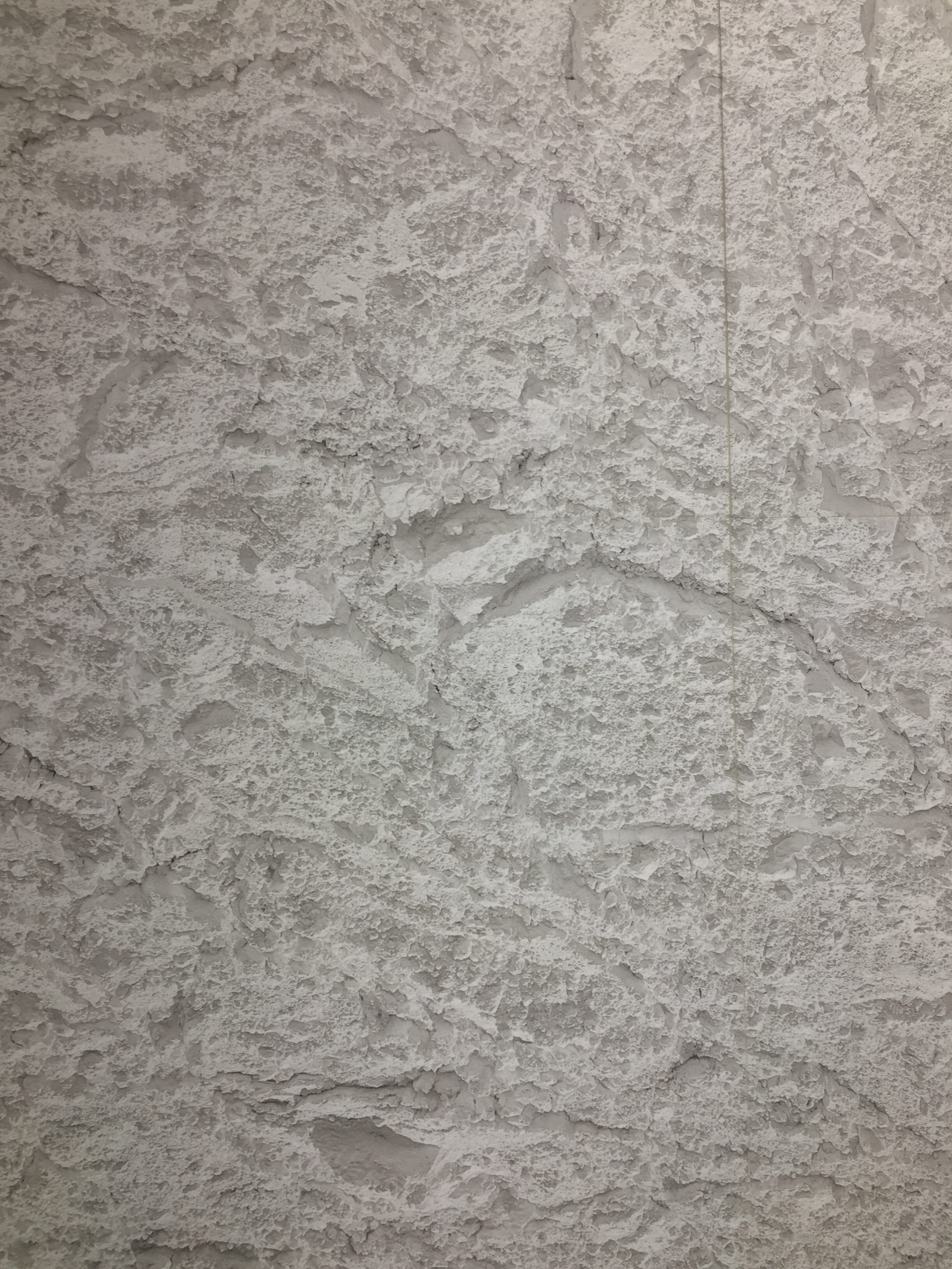

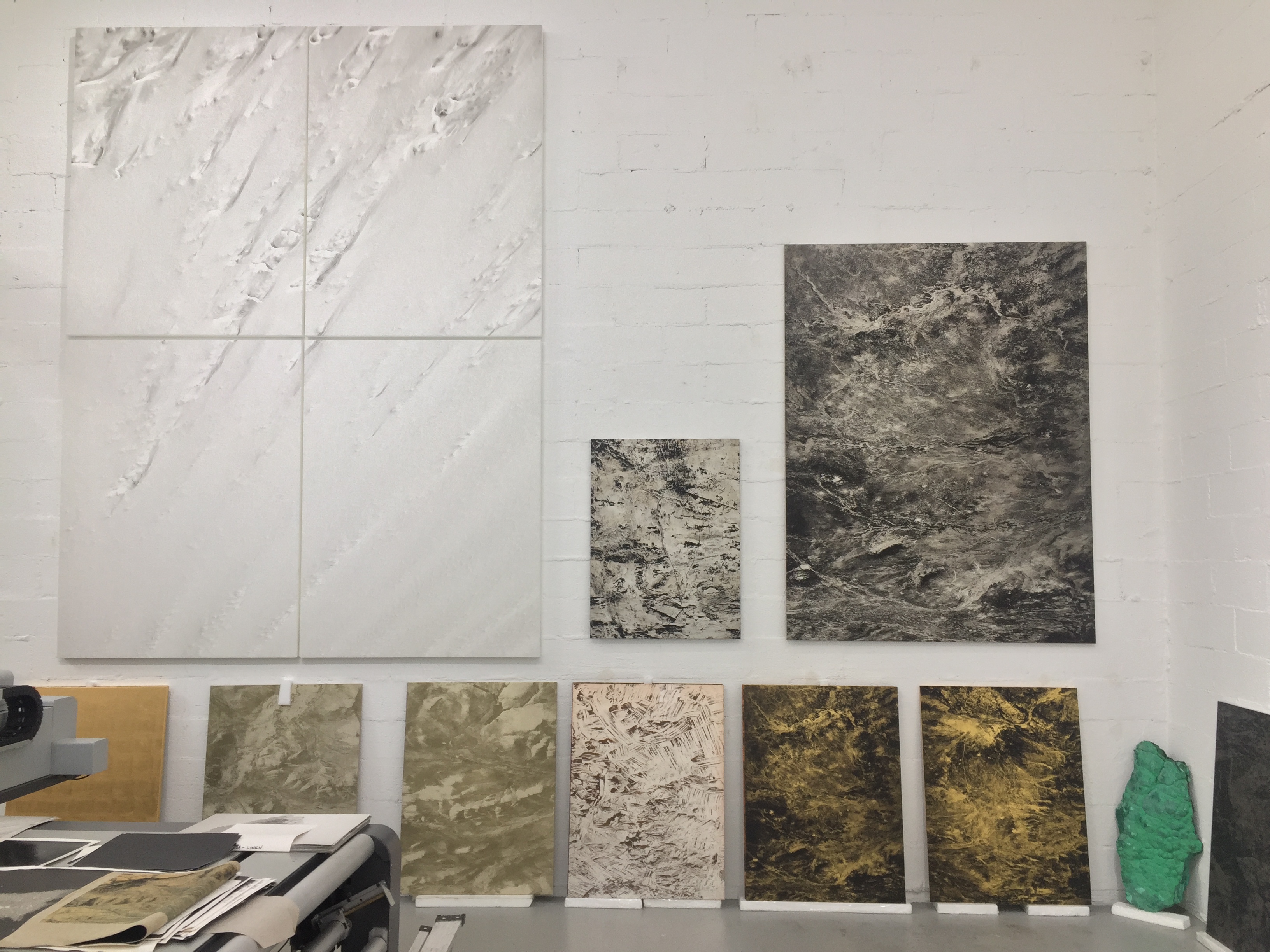

APR 23, 2015 19:08:026 GMT is essentially composed of acrylic ink printed onto virgin polystyrene with a large-scale printer—one of only a handful in the world, according to Guariglia—that he had custom-configured to his needs.

From afar, it looks like a photograph of patchy Styrofoam, white with a scattering of abstract gray lines. But step up close, and the image assumes a 3D quality that practically envelops you into the ice—a trompe l’oeil that took Guariglia several months of experimentation to achieve.

The effect is so engrossing that I had to lean around the side of the print to make sure it wasn’t actually textured. And even though I knew the image was taken from 1,500 feet above, I still couldn’t comprehend how big the mélange was, or how close I was to it.

True to the essence of hyperobjects, APR 23, 2015 19:08:026 GMT is a staggering thing to fathom.

For nearly two decades, Guariglia worked as a photojournalist, shooting for The New York Times, National Geographic, and Smithsonian. Several years ago, he switched tracks to start creating more transcendent work.

“I got tired of the document, of the print on paper,” he says. “I wanted people to stop and look at the picture. I don’t want you to be able to sit there and digest it and absorb it in like half a second, and then [think] what’s next?”

He became fixated on the idea of how humans are altering the natural environment, especially in terms of climate change, he says. He started working on projects about sacred forests and jungles, and taking aerial photographs of agricultural and mining lands from thousands of feet above ground.

By early 2015, he ended most of his editorial work and moved from Taiwan to New York to focus on art, experimenting extensively with different processes and materials.

Then one day Guariglia came across a NASA image of glacial ice online. He mistook it for one of his own aerial photographs.

It was enough to inspire him to cold-call NASA and ask to join a future terrestrial mission as an artist. NASA agreed: If Guariglia could pay his own way and get there as soon as possible, he could take any empty seat on a plane flying on the agency’s Operation IceBridge mission in Greenland, which has been studying changes in the thickness of sea ice, glaciers, and ice sheets.

Guariglia arrived at the airport a couple days later and made his way north. He took thousands of images by plane during his 10-day excursion, including the one that became APR 23, 2015 19:08:026 GMT.

After his work with Operation IceBridge, Guariglia met Josh Willis, the lead scientist on Oceans Melting Greenland, also known as OMG. This NASA mission, slated to run until 2020, is studying ocean-ice interactions.

“We know that the Greenland ice sheet is melting, and we know that it’s getting warmer. But we don’t have a good idea of how much it’s melting because of the warming water as opposed to the warming atmosphere,” Willis says. “So what OMG is trying to do is quantify how much of the ice loss is caused by changes in the ocean, as opposed to changes in the atmosphere.”

The OMG team has already measured bathymetry by ship and gravity by airplane (gravity measurements can help researchers determine the shape of the seafloor), and the scientists will also measure glacier height by radar and ocean temperatures and salinity via probes dropped into the sea, says Willis.

Guariglia plans on joining the mission next year as an artist collaborator. (He must fund his own travel.) His work will entail “art based on OMG data and scientific discoveries that we may have,” Willis says, “in hopes of trying to inspire people to think more about climate change, and how this gigantic ice sheet—which has survived for hundreds of thousands of years—is sort of on the brink of vanishing in the next few hundred.”

Guariglia is undaunted by the challenge.

“My job as an artist is really to engage these ideas and try to create new languages that stimulate people to think,” Guariglia says. To him, climate change “is the most important existential issue of our time.”

Chau Tu is an associate editor at Slate Plus. She was formerly Science Friday’s story producer/reporter.