Meet The Death Metal Singers Changing Vocal Health Research

With cameras down their throats, metal singers show how they produce growls, screams, and squeals without damaging their vocal tissues.

Vocalist Mark Garrett (center) with fellow members of the deathgaze band Kardashev. Credit: Julian Morgan

Last month, Mark Garrett found himself in a lab in Salt Lake City with needles jabbed in his throat, screaming like a demon. The needles ached, but Garrett wasn’t howling from pain. As lead singer for the band Kardashev and a longtime death metal vocalist, Garrett has spent years grunting and growling in his songs and teaching others how to do it on his YouTube channel. But it wasn’t until recently that he thought his otherworldly sounds might be useful to science.

Now, Garrett and eight other singers from acclaimed death metal bands have formed an unlikely partnership with University of Utah scientists to examine the biomechanics behind vocal distortion. Funded through a $300,000+ Kickstarter campaign, the study is the first to use such a wide array of tests, including throat cameras, biofeedback readings, and MRIs, among others, to examine the entire vocal tract of screamer-singers and understand how they use vocal organs in unique ways. What they’re finding upends conventional wisdom on vocal health and could open new avenues of speech treatment.

“Back in the day, you’re just in a basement playing shows and you’re sweating and swinging on everybody in the mosh pit, and you learn [harsh vocal techniques] as you go,” Garrett says. “I think it’s cool that this study is going to bring a lot of new information to what we do know already about extreme vocalization.”

The study didn’t start in mosh pits—it began with opera. In 2021, Elizabeth Zharoff, a classically trained opera singer and vocal coach who runs The Charismatic Voice YouTube channel, began analyzing vocal techniques in songs across a broad spectrum of musical genres. Her fans requested analyses of harsh vocal artists, and every time Zharoff heard a screamer-singer slip seamlessly from melodic “clean singing” into animalistic distortion and back again, “it broke my brain,” she said in one video.

As part of her opera training, Zharoff had undergone vocal health checks for years and was always told that distortive sounds destroy the internal structures required to sing. But these artists, many of whom had been professionally demon growling for decades, showed no auditory signs of vocal damage.

Having viewed camera footage of her own throat—a procedure called an endoscopy—many times, Zharoff wondered what harsh singers were doing that was so different and whether they were paying a physiological price. After she analyzed “To the Hellfire,” a song by the band Lorna Shore, and later interviewed lead singer Will Ramos, she cautiously asked if he was curious about the science underlying his screams.

In 2022, Zharoff and Ramos headed to the lab of Dr. Amanda Stark, a research scientist who studies voice, swallowing, and upper airway disorders at the University of Utah. Soon, Ramos was doing high-pitched teakettle screams, pig squeals, and goblin, pterodactyl, and moose screams, all with a camera in his nose and throat. (You can watch in the video below.)

“We started to call him our unicorn because he was able to create a pretty extensive inventory of very, very unique sounds in a very controlled manner,” Stark says. “He was like, ‘Oh, I can just turn that pig squeal on right away.’… When an artist has that level of control, it makes it much easier to study those sounds in isolation, rather than what we hear on a produced song.”

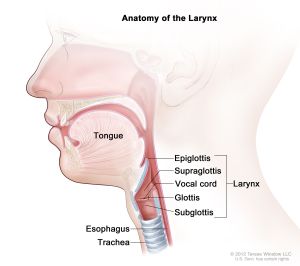

Stark’s team found that not only were Ramos’ vocal tissues healthy, but he was also moving structures in his larynx in ways that clean singers usually don’t and incorporating other structures that aren’t typically associated with singing. In clean singing, air moves from the lungs into the larynx, a tube in the neck that’s divided into three sections: the lower subglottis area, which regulates breathing; the glottis in the middle, where passing air vibrates two muscular “true” vocal folds, creating sound; and the upper supraglottis area where structures like the upper throat, mouth, tongue, and nasal cavity amplify and modify the sound.

The larynx moves a little in clean singing, but when Ramos screamed, his larynx dramatically swung to the side, creating a contortion Stark had never seen before. (See the Ramos twist at the 29:10 mark.) Stark also saw that Ramos heavily used supraglottal structures that couldn’t be viewed on an endoscopy camera.

To find out which supraglottal tissues were moving and how, Ramos and Zharoff created a spreadsheet of different screams, so that Ramos could perform each distinctive sound on cue and while lying down in a scanner. They returned to Stark’s lab in 2024, and Ramos underwent new tests, including an MRI and a laryngeal EMG, which uses needles to place electrodes into the throat to track its muscle activity.

“Our jaws dropped to the floor,” says Stark. In clean singing, supraglottal tissues move minimally, except in styles that involve exceptionally deep tones, like Tibetan chanting and Tuvan throat singing. With Ramos’s vocalizations, supraglottal movement was extreme.

Understanding how harsh vocalists sing in ways beyond the true vocal folds could help performers practice their craft safely and potentially help researchers develop new therapies for patients with injuries and disorders that affect their voices, Stark adds. It could also help doctors provide better care for these artists.

“Sometimes it can be difficult for harsh vocalists to get respect from healthcare,” Mark Garrett says. “I’ve had many students who, they’ll go in and they have some sort of issue and they say that they’re into rock or metal singing and the ENT just writes them off. ‘Oh, that must be it. Stop it and get out of my office.’ They don’t really get actual exams.”

To figure out what’s possible, scientists need more professional screamers. After the tests with Ramos, Zharoff recruited eight more death metal singers and launched the Kickstarter campaign to fund a larger study. This past March, four of those artists—Mark Garrett, Travis Ryan from Cattle Decapitation, Spencer Sotelo from Periphery, and Alissa White-Gluz from Arch Enemy—completed many of the same tests as Ramos.

“When you are starting to look into the back of the throat and doing these different procedures, you’re just struck automatically with how different each one of [these artists] maneuvers their larynx or their vocal tract to achieve very, very similar sounding screams,” Stark says. “There’s just these eye-opening big moments of, like, holy cow, there’s so much uniqueness here on how people can achieve sounds.”

Another four singers, including Tatiana Shmayluk from the band Jinjer—a singer Zharoff calls “the female Cookie Monster”—will undergo testing in the coming months, but not the laryngeal EMG, which Zharoff says caused artists too much discomfort. When finished, Stark’s team will publish scientific papers on the results and, if artists give permission, their anonymized data will be made available to researchers worldwide.

In addition to therapeutic applications, Zharoff hopes that the data comes full circle back to the hallowed halls of opera. “I would love to see Juilliard have a course on vocal distortion,” she says, adding that cross-training in harsh singing can teach performers how to better control larynx and supraglottal tissues. But that’s a while away. For now, she says, “we have so many more questions than answers.”

Christina Couch writes about brains, behaviors, and bizarre animals for kids and adults. Her bylines can be found in The New York Times, NOVA, Smithsonian, Vogue.com, Wired Magazine, and Science Friday.