The Agony, And Reward, Of Passing A Kidney Stone

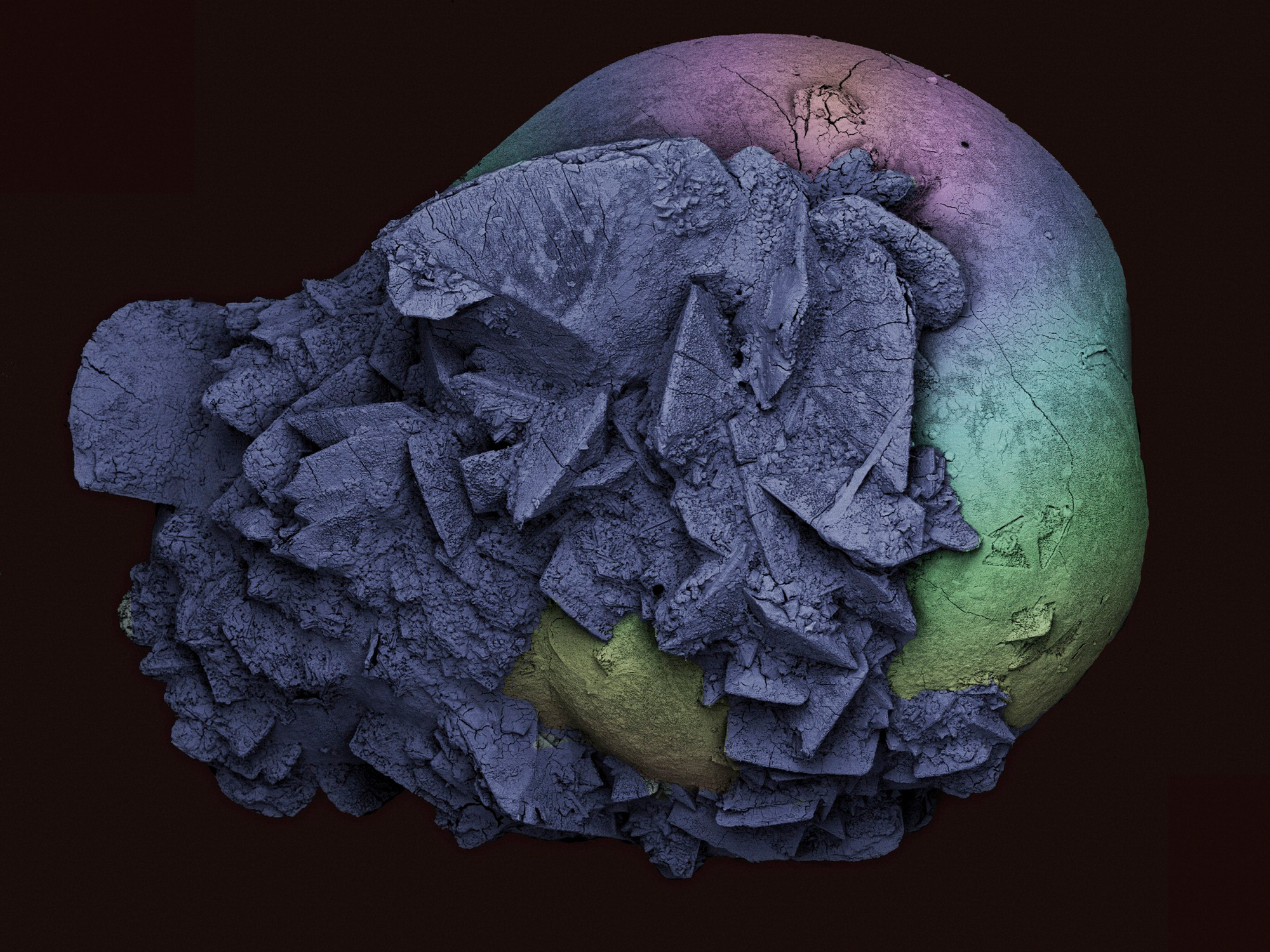

This otherworldly orb with purple projections comes from a surprising source: the urinary tract of its photographer.

Kevin Mackenzie's picture of a kidney stone—from his own body—was a winner in the 2014 Wellcome Image Awards. Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

When Kevin Mackenzie passed a small kidney stone six years ago, it didn’t look like much—certainly not what he envisioned as the culprit behind all his agony. But as manager of the microscopy facility at the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, he has a knack for shining new light on objects. “At life size, [the stone] doesn’t look that painful,” he says, “but it certainly does if you look at it at a higher magnification.” Using a scanning electron microscope, he imaged his stone in black and white, then added color in Photoshop. The resulting picture was one of 18 winners in this year’s Wellcome Image Awards, which honors the most compelling biomedical pictures acquired by the collection.

To some viewers, the eerily beautiful stone may look more like an unusual planet than something produced by a human body—and for at least one of the awards’ judges, that unexpectedness was part of the picture’s appeal. Catherine Draycott, head of Wellcome Images, remarked that it appears “paradoxically like something from another galaxy, with its dark and subtle colors and sense of floating weightless in space.”

Unfortunately for Mackenzie—and about one in 11 Americans—kidney stones are all too terrestrial a phenomenon. The small, millimeter-sized ones can be passed, but centimeter-sized stones usually require surgery. The stones form when salts and minerals become too concentrated in the urine and precipitate out, according to Fredric Coe, a nephrologist at the University of Chicago. In the majority of cases, that precipitate is calcium oxalate.

Coe says Mackenzie’s image clearly shows two forms of the calcium oxalate crystal. The smooth globular section is a monohydrate crystal (so-called because the building blocks of the crystal lattice each contain a single molecule of water) and “is usually toward the base of the stone where it grows on the kidney’s surface,” he says. The jagged piece jutting outward is a dihydrate crystal. “Whether [kidney stones are] spikey or not, I’m sorry to say, they cause a lot of pain,” says Coe.

One way to become a calcium oxalate “stone former,” as Coe calls sufferers, is to have excess calcium or oxalate in the urine. Oxalate comes from a variety of foods but is especially abundant in dark green leaves, pepper, and chocolate. “It’s absorbed through the intestines into the bloodstream and has no where to go but the kidney,” he says. Stones can also occur when the body has too little water. Habitually dehydrated people, such as chefs who work in hot kitchens, are especially at risk.

Among the biggest determinants for kidney stones is a genetic predisposition for calcium buildup in the urine. “If you have a high urine calcium, then 50 percent of your immediate blood relatives are going to have that same high urine calcium,” Coe says.

Calcium, of course, has its virtues. “Calcium is regarded by our body as one of the most important ions,” says Jianghui Hou, an assistant professor of internal medicine at Washington University in St. Louis. For example, the kidneys reabsorb calcium from the urine and send it back into circulation so it’s available for building bone. But sometimes that process goes awry.

Hou has been investigating how the kidneys control the amount of calcium left in the urine by studying claudin-14, a protein that blocks calcium from being removed from the urine and sent back to the blood. Mice on a regular diet have low levels of claudin-14, but when put on a high calcium diet, claudin-14 increases, which ultimately results in a buildup of calcium in the urine. Those findings jibe with a recent study that found that people with mutations in the claudin-14 gene are at higher risk for kidney stones.

Hou is patenting an antibody that detects claudin-14 levels in the urine that could be used as an early diagnostic for kidney stone susceptibility. He ultimately hopes to find a drug that can lower the amount of claudin-14 produced by the body. “We are on the right track to eventually give patients a much better drug to control kidney stones,” Hou says.

That would be reassuring to Mackenzie, who hopes his stone—dazzling as it is—is his last, despite the award.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Jessica McDonald is a health reporter for WHYY, Philadelphia’s public radio station. She is also a former Science Friday web intern.