Ask an Ophthalmologist: Bringing Your Eye Questions Into Focus

21:26 minutes

Ever wonder if too much screen time could hurt your vision? Or do you muse about the origins of “floaters”—those specks or cobweb-like clumps that occasionally wend their way across your vision? Ophthalmologists Lisa Park and Anne Sumers bring your eye questions into focus during this installment of our “Ask an Expert” series.

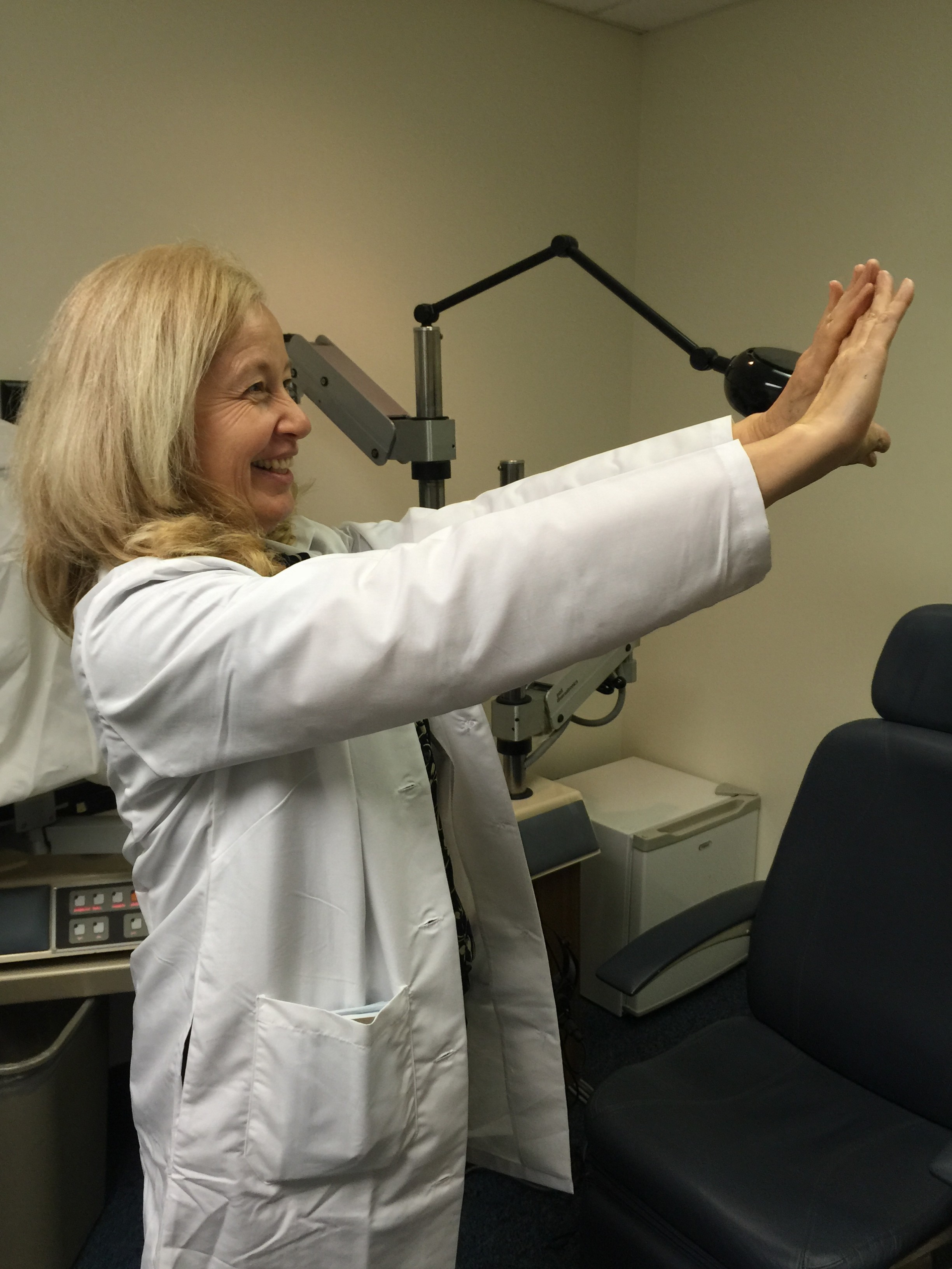

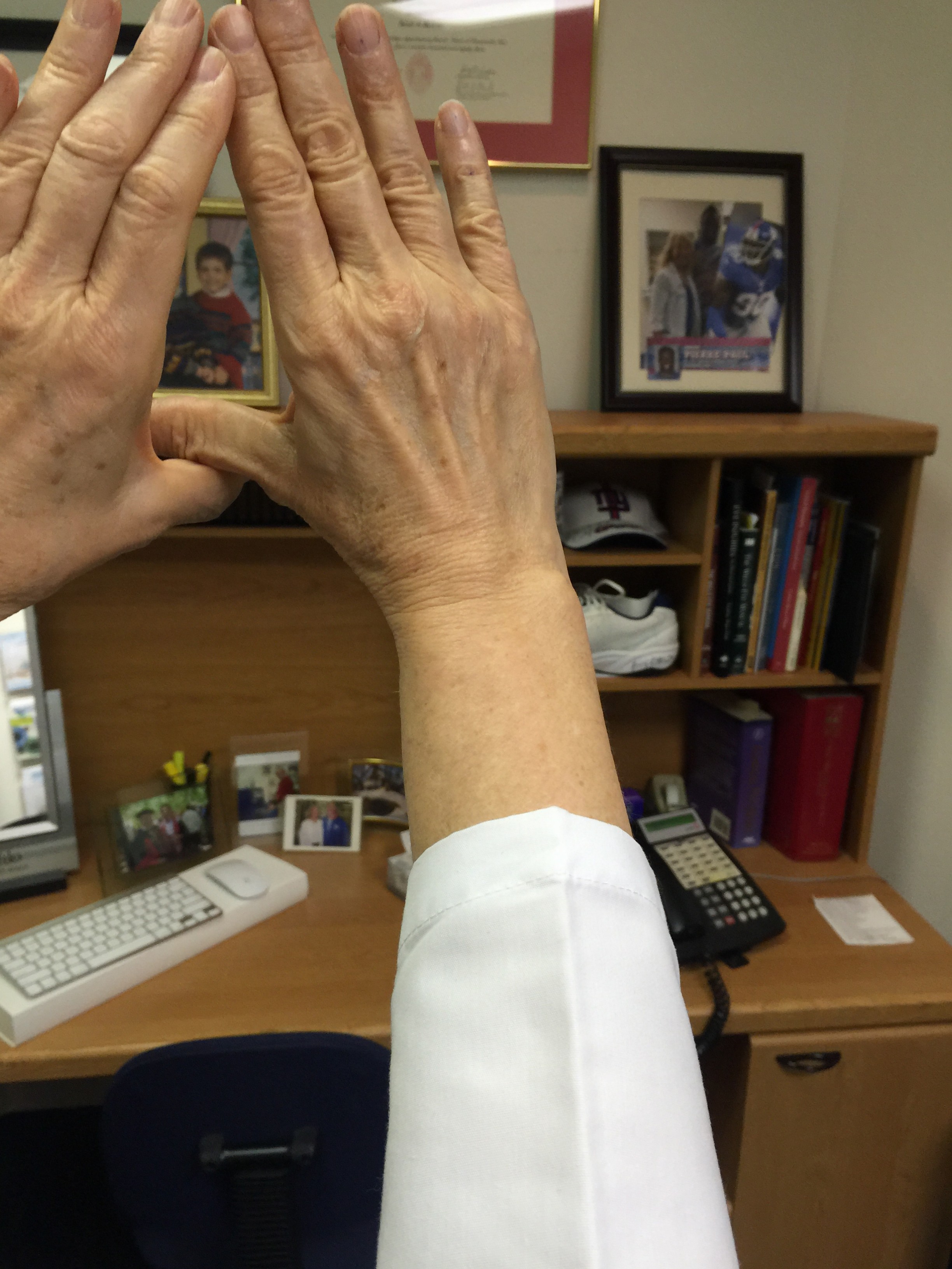

From Dr. Anne Sumers, here’s an experiment you can try to determine whether your right or left eye is dominant.

I picked this cute picture of my boys when they were in preschool.

To do this, put the tops of your pointer and middle fingers together so they touch, and then rest your thumbs one on top of the other.

If you can still see the object, your right eye is dominant.

If you close your right eye and can still see the object, then your left eye is dominant.

Lisa Park is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at the NYU Langone Medical Center, and Associate Director of Residency Training at the NYU School of Medicine. She’s also Chief of Ophthalmology at Bellevue Hospital Center and Co-host of The Ophthalmology Show, on Sirius XM’s Doctor Radio. She’s based in New York, New York.

Anne Sumers is an ophthalmologist at Ridgewood Ophthalmology, and is Spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. She’s based in Ridgewood, NJ.

IRA FLATOW: We’re going to continue our vision theme. Speaking of vision, who hasn’t heard this warning from mom– don’t read in the dark! You’re going to ruin your eyes! It’s a favorite line among parents, especially when bedtime rolls around. But is there any truth to it?

Or maybe you’ve heard some variation on this headline. Don’t give up your eyes for an iPhone, right? Should you be worrying about the effects of all that screen time on your eyeballs?

It’s the kind of question you might ask your ophthalmologist. And if you weren’t so busy answering the question, which looks better– this, or this? This? You know, what goes on at the ophthalmologist.

Well, you can now ask an ophthalmologist. It’s the latest installment in our Ask An Expert series. The eye docs are in. We’re going to help bring your eye queries into focus.

SPEAKER 2: Oh no.

IRA FLATOW: Yes, first of many puns this hour. If you’re a contact wearer, ever wonder what do you do if you fall asleep in– with your contacts on? Sometimes they get a little stuck. Or what about when your eyes all start pulsing? What’s going on there too?

Well, our number 844-724-8255, that’s our number. It’s 844-SCI-TALK. You can also tweet us at Science Friday. @scifri is our handle there.

And we’re going to be doing Ask an Ophthalmologist. And let me introduce them. Lisa Park is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at NYU’s Langone Medical Center here in New York. She’s also the co-host of Doctor Radio’s The Ophthalmology Show on SiriusXM. Welcome.

LISA PARK: Thank you. Thanks for having me today.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Anne Summers is a ophthalmologist at Ridgewood Ophthalmology across the river in Ridgewood, New Jersey. She’s also a spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Welcome to Science Friday.

ANNE SUMMERS: Wonderful to be here. I’m very excited.

IRA FLATOW: We were talking a little bit before that. When you go to a party or something, you get cornered, right?

ANNE SUMMERS: Always. People come up and they say things to me like, I have dry eye. I’m using these artificial tears. Here, let me get my purse. I’ll show you what I’m using. What do you think?

Or I had someone come up to me in church once who said, I can’t see out of part of my eye. It started last night and it doesn’t hurt at all. You don’t think it’s a problem, do you?

And I absolutely knew from her description– new flashes of light, new floaters, Lisa will check me on this– she had a retinal detachment. And I could tell her right there at coffee hour, your retina is off. But she said, but it’s painless.

Everyone’s curious about their eyes. Everyone worries that wearing reading glasses will make you more dependent on glasses. No, reading glasses– your eyes are going to get worse no matter what you do.

IRA FLATOW: OK. So you get cornered with the same–

ANNE SUMMERS: [INAUDIBLE].

LISA PARK: Absolutely. The number one question that I get asked is because– for those who are in the studio, you can see– I’m wearing glasses.

IRA FLATOW: Me too.

LISA PARK: And so people are always very suspicious. Why is the eye doctor wearing glasses? And what I tell people– because everyone asks me about laser vision correction and using LASIK or various other means of reshaping the front surface of the eye in order to get rid of glasses– and what I tell people is it’s a great procedure for the right candidate.

And so the most important thing is to be evaluated fully by an eye MD, an ophthalmologist who’s experienced in doing advanced testing of the eye to determine whether you’re a good candidate. And not everybody is, and it turns out that I’m not. And so–

IRA FLATOW: So you should respect a doctor who says no.

LISA PARK: That’s right. Absolutely. And that’s an important thing. To operate on somebody who has potentially good vision and to run the risk of losing that best-corrected vision is something to think very carefully about.

IRA FLATOW: All right. We’re going to think carefully about taking our calls when we come back, as we have melted down the call board.

[LAUGHTER]

I know, but you can still call. Our number is 844-724-8255, 844-SCI-TALK. You can also tweet us. If you can’t get in by phone, you can get online @scifri, S-C-I-F-R-I. Lisa park and Anne Summers is here to answer your calls. We’ll be right back to talk to an ophthalmologist after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about your eyes, everybody’s eyes. And it’s your chance to ask an ophthalmologist.

And if you have a question, give us a call. Our number 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri.

Our ophthalmologists on call today are Lisa Park, clinical associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at NYU’s Langone Medical Center in New York. She’s also co-host of Doctor Radio’s The Ophthalmology Show on SiriusXM. And Anne Summers, ophthalmologist at Ridgewood Ophthalmology in Ridgewood, New Jersey, a spokesperson for the mayor– the American Academy of Ophthalmology.

I want to give out what– the same caveat I do every time we talk to doctors, we cannot really give you any personal medical advice. It’s unethical for us, and we’re not going to do that. But we can answer questions in general.

And the first question I have is– I’m going to ask you, Anne. Here’s something I didn’t know, that we actually have a dominant eye, just like we have a dominant hand.

ANNE SUMMERS: Absolutely. All of us have a dominant eye. Some people can switch back and forth. But it’s really, really useful, because once you hit 40 or over, you start to need reading glasses. And what we can do is we can fit people with contact lenses where they can see well for one eye for distance, one eye for near.

Because you have a dominant eye, we set the dominant eye for distance and the non-dominant eye for near. So that I, for instance, I can– I’m over 40– so I can play squash, play tennis, do eye surgery, drive my car to New York, all with one set of contact lenses and no reading glasses. And it’s just marvelous. When we do intraocular lens surgery, when we do cataract surgery, we also offer that to people often. It’s called monovision. It sounds bad, but it’s a wonderful, wonderful thing. And I think there’s a simple test. Did you put it on your website?

IRA FLATOW: We had. Yes, we–

ANNE SUMMERS: How you do it? Oh, good.

IRA FLATOW: We have a website. It’s sciencefriday.com/eyes.

ANNE SUMMERS: It’s really cool.

IRA FLATOW: But I’m interested in hearing. Well, as a tennis player, you have a lens that you use for all your sports?

ANNE SUMMERS: Absolutely, absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: Because of the dominant eye?

ANNE SUMMERS: Yes, absolutely. I have a great game, by the way.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: We’ll have to talk about that more later.

ANNE SUMMERS: We’ll play, we’ll play.

IRA FLATOW: 844-724-8255. The first question people want to know is what’s the difference between an optometrist and an ophthalmologist?

LISA PARK: Sure. Well, they’re both categories of eye care providers and can provide much advice regarding the eyes. The main difference is that an ophthalmologist is an eye MD, a medical doctor, so somebody who’s attended medical school and studied the medical underpinnings for eye disease. And the second is that ophthalmologists are the ones who can not only prescribe medications and eye drops, but also do all of the eye surgery that is used to treat eye conditions. So that’s the main difference.

Oftentimes, if you go to some place, like if you go to the mall and you go to an eyeglass store, they’ll have an optometrist there who will check your eyes and give you a prescription for glasses. But for any interventions, treatments, surgery– like the LASIK we talked about earlier– that’s somebody you go to an ophthalmologist for.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s go to the phones, because that’s what we’re talking about, ask an ophthalmologist. And our first question comes from Cameron Park, California, from Sharon. Welcome to Science Friday.

SHARON: Thank you so much. I was wondering with macular degeneration, when is it appropriate to stop driving?

ANNE SUMMERS: Oh, well, the state of California will tell you that, because– this is Dr. Summers answering the question for that one– because each state will determine what your vision has to be with best possible glasses. So if for instance, in New Jersey, it’s 20/50. If you can’t see the 20/50 line, you can’t have a license.

If you have a very small, constricted visual field, if your peripheral vision is very bad, you can’t have a driver’s license. So it’s really a matter of safety, and the DMV, and your own judgment. Do you have macular degeneration?

IRA FLATOW: She’s gone.

ANNE SUMMERS: Oh, gone.

IRA FLATOW: She’s gone, yeah. Let’s move. We’ll stay in California, but let’s go to Berkeley, to Frank in Berkeley. Hi Frank! Welcome to Science Friday.

FRANK: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

FRANK: So my question. I heard a long time ago that you could exercise your focusing muscles looking far away in the distance and then looking close up, back and forth, back and forth, to maintain good vision. Is that true, or is that ridiculous?

LISA PARK: That’s an interesting thing. And of course, any time we exercise part of the body, it’s always a good thing. However, when it comes to the eyes, one of the things that Anne alluded to a little earlier is the fact that over the age of 40, the ability to see close gets harder and harder, and that’s just a natural thing. People come to my office and they say Dr. Park, you made me old, when I tell them they need reading glasses.

And I say, no, no, no. This happens to everybody, and exercising or trying to do things to prevent that from happening unfortunately doesn’t really work so well. And so it’s a natural progression. Again, there are some people who have certain conditions where they can benefit from what we call pencil pushups, looking at a pencil closer and closer to their eyes, but that’s for particular types of conditions. And so the vast majority of people, I’m going to say use your eyes and don’t worry about exercising or not exercising them.

IRA FLATOW: We keep hearing that as you get older, you get far more farsighted. You need glasses. I discovered that as I got older my astigmatism got better. What is going on there? I’m reading better. It seems–

ANNE SUMMERS: Well, astigmatism is a separate thing. You’ve become probably more nearsighted. Your near sight’s gotten better, but your distance vision is not so good. People who are nearsighted will always have good near vision, but when they need to look in the distance, they need the glasses for distance, and that makes their distance vision blurry. So you won’t lose that near vision.

Astigmatism usually doesn’t change. Astigmatism means there’s one power in one direction and one power in the other direction in that lens that’s required to see. Unless you have a disease called keratoconus, it’s unlikely to have the astigmatism itself change.

But the lens is a living thing. The lens changes in your eye. And so through– we encourage people to come back and see us every two to three years who wear glasses, because the glasses change, and the contacts change, and the vision for distance and for near changes.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to someone who has a question about this, Brock in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Hi, Brock.

BROCK: Hey. How’s it going, Ira?

IRA FLATOW: Hey there.

BROCK: Yeah. My question is this. I do have keratoconus in my right eye, and I was wondering if it is possible to have it fixed LASIKly or surgically, or is it just something that I’m going to have to deal with for the– I’m 40, so I don’t mind, whatever. And I’m not looking around.

IRA FLATOW: Lisa Park?

LISA PARK: Yes. This is a very interesting question. So keratoconus is a condition where there is progressive worsening astigmatism associated with thinning, what we call steepening, of the cornea. And so the first thing I will say is that you absolutely would not be a good candidate for laser vision correction. That is something that is really a contraindication, simply because when there is progressive thinning it becomes dangerous to do laser to– that reshapes that part of the cornea.

That being said, we do know that there are patients who have progressive thinning of the cornea that actually starts to stabilize if– especially if you’re around age 40. And so if your astigmatism can be corrected with contact lenses, especially the rigid contact lenses are usually the best to give you the best vision in a person with keratoconus, there’s something that we should– I should mention also that there are treatments to stabilize keratoconus and these are known as collagen cross-linking on the cornea.

This is something that’s being done widely throughout Europe and is not FDA-approved yet in the United States. But it’s something that all of us know a lot about, and we’re eager to have that come to be an FDA-approved treatment, but it’s something we want to investigate. So collagen cross-linking is something that we usually do in keratoconus.

IRA FLATOW: Well, good luck to you, and thanks for calling. Our number 844-724-8255. Let’s talk about the 800-pound gorilla in the room, one that everybody wants to know about.

LISA PARK: And that’s not Ira.

IRA FLATOW: No.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: I’m only 750.

[LAUGHTER]

Lost a little weight. And that is what every mother is telling their kids. Don’t read in the dark. You’re going to ruin your eyes. Well, of course you can’t read in the dark, but in the dim light you’re going to ruin– is that true, or what’s–

ANNE SUMMERS: Absolutely not true. No.

IRA FLATOW: Not true.

ANNE SUMMERS: No. Children can see better in the dark than we can. A child of 10 will see better in the dark. And my child, I remember going up to see his room. At one point, Ben was trying to do his Spanish homework underneath the covers because I told him to go to bed, and he was trying to get it done. So I thought it was amazing he could see.

As we get older, our night vision is not as good as it is when you’re young. But reading, using your eyes for distance or for reading, wearing your glasses or not wearing your glasses, glasses are neither a crutch nor are they therapy. Glasses, unless you have crossed eyes or lazy eye, glasses just help you see better.

There’s been some studies showing that maybe children who read with great intensity and don’t go outdoors much have a much higher risk of nearsightedness, and there is an epidemic of nearsightedness going on. There was one study that came out that said five billion people are going to have nearsightedness in 2050. It’s going to be an enormous– and there was another study that in Korea, 95% of the kids who are 18 years old are nearsighted at this point.

IRA FLATOW: But why? Do you know why?

ANNE SUMMERS: Well, part of it is we think the kids are on the screens and on their iPhones and inside. And there was a study showing that if the kids go outside for 40 minutes a day and play outside, the progression of nearsightedness is less. But it’s an interesting– and this is not just a little bit of nearsightedness, not minus 2, minus 3, minus 4, but this is minus 10, minus 12– very, very nearsighted.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones and ask a related question. Let’s go to Washington with Marti. Hi, welcome to Science Friday.

MARTI: Hi. Thank you. Yeah. I have cataracts, and I’m wondering how the multifocal lenses for cataract replacement are faring.

IRA FLATOW: Lisa?

MARTI: I’ve been told they’re not very good.

LISA PARK: Sure. So what the multifocal implant is, when we remove a cataract, we replace it with an artificial lens. And the lenses are made out of a type of material like acrylic and the vast majority of people get what’s called a monovision, a single-vision lens. And as we were talking about earlier, if you’re able to see a distance with this lens, then you’re not able to read without reading glasses.

The multifocal is a premium lens, usually not covered by insurance, and it has multiple rings in it. Some are focused at distance and some are focused at near. So this enables to give you a range of vision and get you out of glasses for a large proportion of the things that you do– not for everything, not for 100%, but it can.

What I always tell my patients is that you always got to give up something to get something. So what do you give up? You give up your best possible vision at any particular focal length. And it’s just something that if you feel that you want really perfect vision at a particular– in distance or for reading, just understand you’re going to give up a little bit of that to get the freedom to get out of your glasses.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask you as a follow-up. Parents may have heard of these ortho-k contact lenses that are being prescribed for nearsighted kids. Are these any good?

LISA PARK: I think that’s a very good question. So the ortho-k, it is something that we’re seeing in greater numbers. And what this is is this is putting a device on the surface of the eyes, usually while children are sleeping, in order to reshape, sometimes flatten the cornea so that they’re able to have a particular focal length when they wake up. The number one thing I will tell you is that it’s not permanent. So in other words, you’re flattening or reshaping, and it’s not something that is going to prevent the development of nearsightedness or change the eye permanently in any way.

The other thing I will say is, personally, I don’t recommend, especially young people, put things and sleep with them on their eyes overnight. When I was a medical student, there was a study that made the front cover of the New England Journal of Medicine showing that if you sleep in contact lenses, you increase your risk for corneal ulceration, which is a scratch and an infection on the cornea, by tenfold. And these kinds of infections can be devastating, and so it’s something– just that you’re running that risk when you do something like that.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let’s go to Sue in Rochester, New York. Hi, Sue. Welcome to Science Friday.

SUE: Hi. Thank you very much. I was wondering if you could discuss closed-angle glaucoma, and maybe some of the causes and the current– and then treatments for glaucoma– the closed-angle.

ANNE SUMMERS: Sure.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Summers, yeah.

ANNE SUMMERS: Sure, absolutely. There’s two kinds– or there’s many, many, many different kinds of glaucoma, but two major forms. 90% of glaucoma is open-angle glaucoma.

It has no symptoms. You don’t know you have it until you have irreversible peripheral visual loss. Early diagnosis, early treatment with simple drops, prevents blindness. That’s the open-angle glaucoma.

Narrow-angle glaucoma is much less common in the United States. It’s more common in Japanese and Chinese people and very farsighted people. But narrow-angle glaucoma, you have no symptoms until one day you wake up or you are walking down the street and you get pain, nausea, redness, and perhaps irreversible loss of vision.

That is a medical emergency. It requires a laser treatment of the iris that takes about five minutes, and it will prevent loss of vision. And the pain goes away, and the eye hopefully is not damaged. When we see narrow-angle in a patient, we follow this angle carefully, and we will do a preventative laser iridotomy. Again, takes five minutes, and it will prevent you from having an angle-closure glaucoma attack.

So a lot of times patients, when they come in, I look at their eye and I say, your eye has narrow angles and you need to have this laser treatment. And they say, but I have no symptoms. Well, we’re not going to wait till you have them.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, talking with Lisa park and Anne Summers about ophthalmology. Here’s a tweet that came in from Nellie Kepler. It says “If you wear glasses– meaning bifocals– is there any advantage to asking your eye doctor about computer glasses?”

LISA PARK: So as Dr. Summers mentioned earlier, wearing glasses or not wearing glasses, it all becomes a matter of what you want to see and at what distance you want to see it. And so if you’re spending a lot of time at the computer and finding difficulty in a bifocal, trying to find that sweet spot where you can see very clearly, then I would say absolutely. It sounds like a great idea to get a pair of dedicated reading glasses.

And I usually tell my patients, you just leave them by the computer. When you’re on the computer, you put them on. It gives you a mid-range distance of focus, and it can make things very comfortable for you.

IRA FLATOW: And Dr. Summers, one question about floaters.

ANNE SUMMERS: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: When should we worry about them? They’re a normal part of aging, are they not?

ANNE SUMMERS: Absolutely. Nearsighted people often get floaters in their 20s and 30s. And these are just when you look up at a blue sky or a white board, you’ll see little things floating around. And that’s little degenerated cells in the vitreous of our eye.

It’s like a tennis ball with a little jelly in it, and these little specks don’t go away. Those are our regular floaters. But if you notice many new floaters, persistent flashing lights, loss of vision over part of your eye, that is a symptom of a retinal tear or retinal detachment.

And I think a really important message is, I know people say to me, gee, I called to get in with my eye doctor, and it’s a four to six wait– week wait for an appointment. If you call any ophthalmologist with new floaters, flashing lights, loss of vision, or pain in the eye, they will generally say, come right over. We will fit you in.

We always have about– I’d say 20%, Lisa, of our patients every day are emergencies. And eye pain can’t wait. So if you call me, you say I have many new floaters, or I have pain in my eye, or I can’t get my contact lens out, we have those slots open for you, because you can’t say to someone, oh, you have eye pain? Oh, how’s March 17?

[LAUGHTER]

No. You say, come right down. We will fix it right now. And we’re used to that. That’s just part of ophthalmology. Much of what we do is routine with glasses, contacts, glaucoma treatment that’s just preventative, but we are emergency doctors all the time.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I want to thank you both for taking time to be with me. Well, it got– it went by very quickly, hasn’t it? Lisa Park, clinical associate professor in the Department of Ophthalmology at NYU’s Langone Medical Center in New York. She’s also co-host of Doctor Radio’s The Ophthalmology Show on SiriusXM. That’s once every couple weeks?

LISA PARK: Absolutely. Every Tuesday.

IRA FLATOW: Every Tuesday. There you go. Anne Summers, ophthalmologist at Ridgewood Ophthalmology in Ridgewood, New Jersey, and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology. And you can test to see which of your eyes is dominant. We have instructions up at sciencefriday.com/eyes. Thank you both.

LISA PARK: Oh Ira, you’re great.

ANNE SUMMERS: Thank you.

LISA PARK: Thank you. Lots of fun.

ANNE SUMMERS: Thanks for having us.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Annie Minoff is a producer for The Journal from Gimlet Media and the Wall Street Journal, and a former co-host and producer of Undiscovered. She also plays the banjo.