How Grief Rewires The Brain

28:49 minutes

Being a human can be a wonderful thing. We’re social creatures, craving strong bonds with family and friends. Those relationships can be the most rewarding parts of life.

But having strong relationships also means the possibility of experiencing loss. Grief is one of the hardest things people go through in life. Those who have lost a loved one know the feeling of overwhelming sadness and heartache that seems to well up from the very depths of the body.

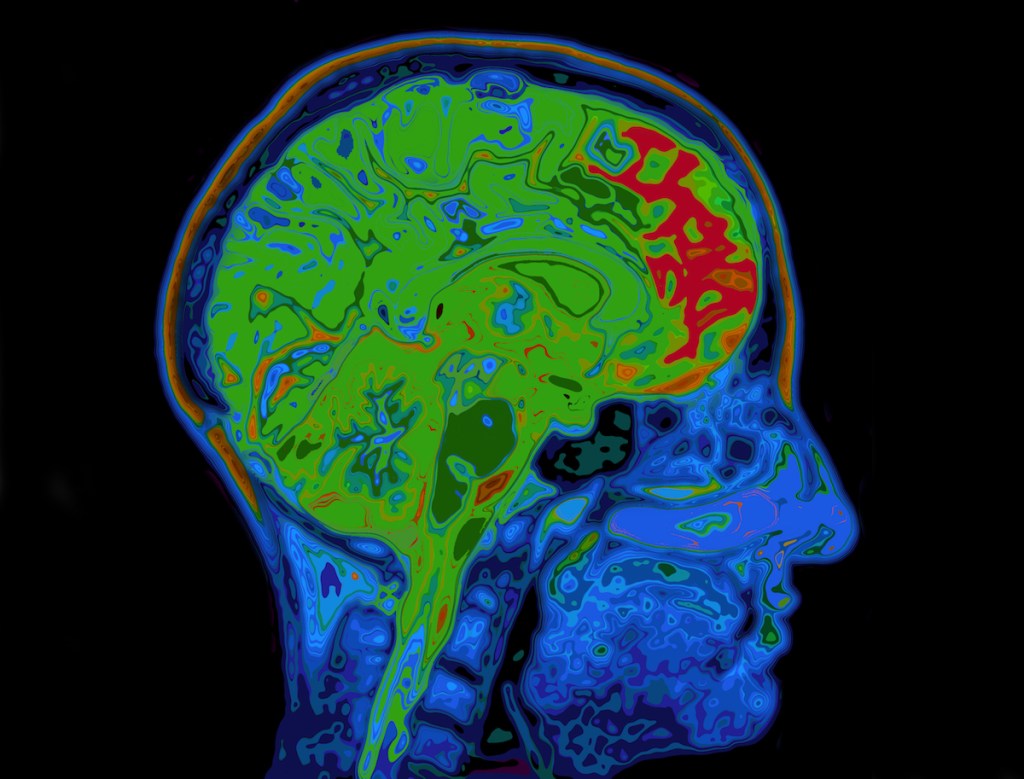

To understand why we feel the way we do when we grieve, the logical place to turn is to the source of our emotions: the brain. A new book explores the neuroscience behind this profound human experience.

Ira speaks to Mary-Frances O’Connor, author of The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Love and Loss, a neuroscientist, about adjusting to life after loss.

This segment was re-aired on May 6, 2022.

Mary-Frances O’Connor is a neuroscientist and author of The Grieving Body and The Grieving Brain. She’s based in Tucson, Arizona.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Being a human can be a wonderful thing. We’re social creatures. We crave strong bonds with family and friends.

Those relationships can be the most rewarding part of life, but having strong relationships also means experiencing loss. Grief is one of the hardest things we go through in life. If you’ve lost a loved one, you know that feeling. It can be an overwhelming sadness and heartache that reaches deeply into the very core of your being.

To understand why we feel the way we do when we grieve, the logical place to turn to is our brain. A new book explores the neuroscience angle to this profound human experience. The author is my guest, Mary-Frances O’Connor, PhD, author of The Grieving Brain, based in Tucson, Arizona. Welcome to Science Friday.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: It’s so nice to be here, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: It’s so nice to have you. Let’s start with some of the wordplay here, if I might. I’m inclined to use the words “grief” and “grieving” interchangeably, but they’re actually different experiences, correct?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: That’s right. I have found this to be really helpful in studying grief and grieving. Grief is that wave that just knocks you off your feet, where grieving is how the feeling of grief changes over time without ever going away.

So what I mean by that is that grief is a natural response to loss. And if I open a drawer, I come across a– my mom’s signature, say, for example, 20 years after she’s died, I may still dissolve into tears on that day. And yet I know that that feeling of grief is maybe more familiar. And so it’s not the same as it was 20 years earlier. But if we’re expecting that we’re not going to feel grief anymore, we may start to wonder if we’re actually getting any better, or if we’re adapting the way people are expecting us to.

IRA FLATOW: You said when you study grief. How long have you been studying grief? And what do you mean by studying grief?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: I have been studying grief for a good 22 years now. I started in graduate school, because fMRI technology was brand new back then, and I was absolutely intrigued. So after my dissertation, we brought people back and put them in the neuro-imaging scanner for the very first study of grief from a neuroscience perspective.

IRA FLATOW: So this was groundbreaking stuff then.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Yes. The American Journal of Psychiatry thought it was, at least.

IRA FLATOW: Well, when you put them in the scanner, what do you ask of them?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: We really struggled with, you know, how do you evoke something as deeply intense and personal as grief in such sterile, sort of hospital-like environment? And what we came up with was what people do pretty naturally. If they’re going to tell you about someone who has been the love of their life, they often open a photo album and show you photos.

And so we scanned photos individuals brought us and took words from the stories they told us about their loss, and projected those onto goggles that people were wearing in the scanner. So we literally had images of what their brain was reacting to when they were each looking at individual photos of their loved lost one, which was a little unusual at the time. Usually, we’d try to have standardized stimuli across everyone. But it is such a personal experience, that felt important.

IRA FLATOW: Please, can you share with us what you’ve learned? Tell us what is going on in the brain when you look at those pictures, or when we lose a loved one.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: You know, one of the things we realized is that grief is really complex. So it actually involves a bunch of different things that the brain is doing all at the same time. And those include things you might expect, like memory and even things like being able to take someone else’s perspective. So encoding of sort of the self and the other. But other things as well, even things like regulating our heart rate and so forth.

IRA FLATOW: You’ve just described how you show pictures to people who are getting their brain scan. And that must dredge up memories, correct? What’s going on in their brain about these memories?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Well, one of the interesting things is the brain is very complex. And we can actually be using two streams of information at the same time. So you’re absolutely right. One aspect is memory. We’re thinking about times we spent with the loved one, maybe even seeing the loved one decline over time or being there when they passed away or getting that phone call to tell us that they have died.

But interestingly, we also have to think about the bond. So in the human brain, there is a bond created when we come to be a parent, or we become a spouse. That bond is very strong and comes along with some beliefs. And one of these beliefs we have is, that person is going to be there for us. No matter what, that person is there.

What that leads to is these two streams of information. On the one hand, you know that they’re gone. But on the other hand, it sort of feels like they’re going to walk through the door again. And so that can be very confusing for people. I think it takes a long time for the brain to be able to predict, no, I’m not really going to see this person again, and all the emotions and what that means that comes along with it.

IRA FLATOW: So does that mean that in the brain, the brain cells have to physically rewire themselves for the new reality?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: That’s exactly right. So even in simple things, say in a mouse, if you put him in a box every day and he sees some blue LEGO item, after a number of days, if you take the LEGO out, and you put him back in the box, there is still a ghost trace of that block. Because the rat is expecting it, there are neurons that fire when he is in the area where that block should be. Now, this persists for a number of days, but imagine, for a life that is so intersected with another person– everything we do and think and plan is involved with this other person– the brain literally has to create new wiring to understand what’s happening.

IRA FLATOW: And that takes time.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: It does take time. It turns out that time is one of the most important things. But actually, experience is another important thing. Something we sometimes see is that people have a lot of difficulty with grief and start avoiding situations or conversations or even people that remind them of the loved one because it’s quite painful. But it turns out that kind of avoiding doesn’t give our brain a chance to learn the new reality.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Grief can feel like such a physical event.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Can’t it?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: It really can. I think it is a physical event, in part because it’s physically happening in your brain. Usually when we say that, of course, we’re referring to the bodily feelings.

But really, those changes– for example, some work by Zoe Donaldson at University of Colorado Boulder shows that there are specific neurons in rodents that pair bond– some of you will have heard of them– called voles. There are specific neurons that are activated just when that vole is approaching their one and only. And the number of neurons increases as that bond gets stronger. And so if you think about, then, all the things that have to happen in order to be able to predict this person isn’t going to be back and understand what that means, it’s pretty complicated, and really is a physical process.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah, you talk in your book, also, about how grief can actually cause physical ailments.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Well, the term “the broken heart phenomenon” is something we think of as a metaphor, or we think about that in terms of sort of a poetic way to put what we’re feeling. But we actually know from epidemiological research that it is true that when a person has lost their spouse, their own risk of mortality goes up. For men, it goes up twice as high than their married counterpart for the first six months. And it goes up in women as well, not quite as high.

And so we know that that connection is a lot about physiological regulation. Being with our loved ones is extremely rewarding, and it feels safe. And so our physiology really has to live in what feels like an unsafe world for a while, and try and figure out how to come back to homeostasis.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because we know that losing a loved one can be very traumatic.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Do trauma and grief overlap?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: We used to think that grief and depression were the same thing. And sometimes we even thought grief and PTSD might be the same thing, depending on how the loved one died. But some work by Richard Bryant at the University of New South Wales in Australia did neuro-imaging scans of people who had a severe form of grieving, and it actually looked different from PTSD and from major depressive disorder in the brain, recruiting different parts of the brain, recruiting the orbitofrontal cortex when people who had this severe grief looked at pictures of people with sad faces. So knowing that there are some biological differences, or neurobiological differences, really reinforces what we see clinically, that PTSD and grief– they are different.

IRA FLATOW: That is interesting. You say in your book that many people who lose a loved one turn to religion to help them understand what has happened and where their loved one may have gone. Is there science that backs up this connection?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: I think, you know, as a neuroscientist, it isn’t so much that I’m trying to figure out if religious beliefs are true, but rather, what does it do for us if we have religious beliefs? So on the one hand, we know often being a religious person comes along with having a religious community. And we know social support is really important. And we can see that in studies.

The other thing that sometimes happens for folks, though, is that they get into a lot of concerns about guilt, sometimes even feeling that they are being punished for what has happened. And this can be really problematic for people in trying to understand the meaning of what they’re going through.

IRA FLATOW: We have to take a break, but when we come back, more about how our brain processes grief with author Mary-Frances O’Connor.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A brief programming note– the spring season of the Science Friday Book Club is about to begin. Starting February 25, we’re reading Sarah Stewart Johnson’s The Sirens of Mars. It’s all about the search for life on the Red Planet. If you want to read with us, go to sciencefriday.com/bookclub. You can sign up for our newsletter, join our community space, and even read an excerpt of the book. That’s sciencefriday.com/bookclub.

If you’re just joining us, I’m speaking with author and neuroscientist Mary-Frances O’Connor about how our brains process grief. Her new book, The Grieving Brain, is out now. Are there medications designed to alleviate or help people cope with grief?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: This is a very important question. And I would say that at this point, we do not have medications. In fact, one of the things that we know is that, as I said before, major depressive disorder and even severe forms of grieving are different things. This was really neatly, sort of elegantly, explored in a study by Kathy Shear at Columbia University, where they did treatment for a severe type of grieving called prolonged grief disorder. And they also looked to see if they had major depressive disorder.

So in one case, they were given just psychotherapy targeted for grief. And then they were either given an antidepressant or not given an antidepressant. What they discovered was antidepressants were very helpful if the person had comorbid depression. We saw their depressive symptoms remit. But the antidepressant did not actually have an impact on those feelings of yearning and wishing that the person was back. That type of emotional pain was not actually helped by the antidepressant. And that was very helpful, again, in helping us distinguish between these difficult experiences.

IRA FLATOW: Do you suspect, though, that when someone is grieving, and it’s quite obvious how much they’re suffering, that somebody– a psychiatrist or their physician– may prescribe an antidepressant just to give them something when they don’t actually need it?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: This is a bit of a challenge. I think there hasn’t been a lot of education in medical schools– frankly, in psychology training, either– about grief. It really is in its infancy. And so often, because, just as you say, doctors are empathic– they see this person, they want to give them something– sometimes they will prescribe an antidepressant, even sometimes when the patient says, I don’t really feel depressed.

But the other problem is that a lot of people who are grieving have difficulty sleeping. And so a doctor will often prescribe a sleep medication. What we know about that is the difficulty sleeping that comes with bereavement is a temporary situation. It is incredibly difficult, but it is also temporary.

And those sleep medications tend not to work well in the long run. And yet people tend to stay on them, sometimes because coming off of them is difficult. So it’s more important to think about, for example, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, what we call CBTI, which is a way of thinking about supporting the natural sleep cycle through behavioral means and enabling that person to get back into a rhythm naturally so that in the long term, they don’t have these sleep difficulties.

IRA FLATOW: Now, your book was written pre-COVID, but it’s very timely for right now, I would imagine. So how much grief is happening in the world because of this virus? I mean, has this pandemic changed how you look at grief in some ways?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: It has in some ways. I think there’s been a lot of discussion about grief. But what we know from evidence in the United States, some modeling done by some sociologists demonstrated that for every person who has died, there are about nine loved ones who remain, who are survivors. So if you think about, we’re getting close to a million people who have died of COVID, that’s 9 million people who are acutely grieving. And–

IRA FLATOW: And that’s just in our country.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: And that’s just in our country. So one of the difficulties is just understanding what it means to have such a large number of people, but also, who are all going through it at the same time. Usually, when we’re losing a loved one, we have people around us who aren’t going through that experience that we can kind of lean on. And now we have a pretty unusual situation where, I mean, let’s face it, we’re dealing with a lot of types of grief, but even if we focused only on bereavement, we’re dealing with a lot of deaths.

And for me, it isn’t just, what does that grief feel like, or how many people have it? But as a grief researcher, my interest is partly in, why might the pandemic circumstances be harder for people who are grieving? And the thing I said before about, the brain relies on this stream of information where we’ve maybe seen the person decline, we may have been there at the bedside when they passed away, we went to a funeral or a memorial service– many of those circumstances have really changed because of social distancing.

And so as I’m doing research right now, I’m talking with people who– you know, the 70-year-old woman who dropped off her fairly healthy husband who had a cough at the ER, and was having some trouble breathing, and then, because we’re not allowed to be in the hospital with them, the next thing she knew, he was actually– she was being told that he had died. And that’s a very unusual circumstance, for us not to be present. People who have loved ones in long-term care experience this as well. And I think the problem is that it doesn’t give our brain a chance to understand what’s happening as we’re going through the experience.

IRA FLATOW: Yes. That, I’m sure, has happened many times, unfortunately. And as you say, we’re experiencing what feels like a group grief event with COVID. Do you think this might change us as a species?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: It’s an interesting question. Certainly, in the sense of a species, grief is such a universal experience. And even pandemics, right, mass casualties– we certainly, as a species, have faced difficult situations before. And we can look to some of those for important ways that people have coped.

I think it’s unusual in a cultural way. Part of what we sometimes forget is that bereavement is a health disparity, right? So 65% of all the children experiencing COVID-associated loss of a caregiver are of a racial or ethnic minority.

And this has always actually been true. Black Americans become widowed at much younger ages. Work by Debra Umberson down at UT Austin showed that between the ages of 65 and 74, 25% of Black Americans are widowed compared with only 15% of white Americans. And so bereavement isn’t affecting everyone equally. If we’re thinking at a kind of public health level, we have to really make sure that the response is targeted in the way that it will do the most help.

IRA FLATOW: If there are people who are listening and who are grieving, what do you recommend they do to lessen the pain or help them move on or find help?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: This is a very challenging time for people. I think it’s confusing. The grief experience is not often what people are expecting. There’s a lot of anger, often, or just the intrusive thoughts. You can’t sort of stop thinking about it.

Much of that is actually pretty normal. And people often have the desire to talk about their experience, to try to put into words what it means to know that you’re not going to retire with this person that you had planned to do that forever. So I actually recommend reaching out and talking with the people around you, especially people who may have had their own grief experience. Often, there’s a level of empathy there that– it can be more difficult for people who don’t have the same lived experience. So reaching out and talking with people.

And also, if people are experiencing things like feeling life isn’t worth living, or feeling they can’t get through the day without drinking a large amount of alcohol, these are really signs that it is important to reach out for professional help, as well, because this is a temporary situation. And although it doesn’t feel like it in the moment, it will change over time. And we want to support a person who’s in that immediate part of grieving in order to help them get onto that sort of healing grieving trajectory.

IRA FLATOW: You know, the news is filled almost every day with someone else suffering a violent death, whether it’s from gunshots, whether it’s from murders, whatever. Is there a special kind of grief that these people, the relatives and the loved ones of these people, go through that needs a special kind of treatment or counseling?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: We sometimes refer to this as traumatic grief, meaning that the situation itself that led to the death was a traumatic situation. And we know that violent deaths and unexpected deaths can be more problematic as people are trying to understand what has happened and what it means for their life. Often, people who’ve experienced a traumatic death experience more grief symptoms.

But often, also, it comes with other things as well. Sometimes there is what we might call survivor’s guilt. So depending on what the situation was, the sort of question to oneself of, why did I live when this other person did not? And that can be complicating as you’re trying to come to terms with what has happened and then learn how to sort of restore a meaningful life.

IRA FLATOW: What research would you like to see on grief and grieving in the future? And if I gave you– I’m going to give you the SciFri blank check question. Maybe you’ve heard it before. If I had a blank check, which I don’t have it, to give you for spending on buying anything you’d like, on the kind of research you’d like to see done that hasn’t been done, how would you spend it?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: You know, I think there are even some really basic questions that we don’t know. One is that we have a number of studies now on grief, that single snapshot in time across a number of people. What we don’t have a lot of research on is actually grieving, so looking at the same person, putting the same person in the MRI scanner numerous times across that changing experience and seeing, what does it look like in the brain when people are coming to terms with what has happened, restoring a meaningful life?

And the second question I would want to know at the same time– we don’t actually know if people who are psychologically having a lot of difficulty adjusting are the same people who are having a lot of difficulty medically adjusting. So we don’t actually know yet– because these tend to be different groups of people studying them– we don’t actually know if the changes physiologically are related to the changes in the brain and in the mind. And so I’d love to see more integrated work over time with people.

IRA FLATOW: When you say medically adjusting, what do you mean by that?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Well, this gets a little bit back to what I was saying about the broken heart phenomenon earlier. What we know is that acutely– and this is true even in animal pair bonds. Some work by Oliver Bosch at University of Regensburg in Germany has shown that when a bond is formed, it’s almost like cocking a gun, so that as soon as there is separation, cortisol goes up, or the animal version of cortisol. Cortisol goes up in humans upon separation and remains high.

So think about that moment when you lose your kid in the mall, and you can’t find them– that utter panic, right? Or think about when a husband even goes on a trip out of town, and you feel awful, right? As soon as that separation happens, we know there are these physiological changes.

And we’re still really trying to understand, in human beings, for whom do those changes happen most? Is that related to how they feel emotionally? And then, are there things that we can do to help sort of support the body as it deals with this stress hormone imbalance in order to improve their experience and even improve their medical situation in that initial period of grief?

IRA FLATOW: Talking with Mary-Frances O’Connor, PhD, author of The Grieving Brain, on Science Friday from WNYC Studios. You told me earlier that you’ve been studying grief for over 20 years. Does it get to you, studying grief?

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: This is a really common question for me. You know, I teach an undergraduate Psychology of Death and Loss course, so 150 undergrads who say the word “death” probably more in that 14 weeks than they ever have in their life. And they often say to me, you know, I feel like you’re too happy to be teaching this class.

And I tell them the thing for me is, the reason I’m happy is because I really understand the suffering. And so I have found a way in my own life, from the death of my mother when I was in my mid-20s and then the death of my father not so many years ago. I know what that suffering is like. And for me, it has helped me to find a lot of meaning in life, to know that working with that one student to help them understand something is really rewarding because this is all the time we got.

So I think the surprising thing is, for people who have found meaning, it can be very powerful. And that is sort of an unexpected side to grieving.

IRA FLATOW: Well, that’s about all the time we’ve got. Mary-Frances, thank you for taking time to be with us and for this terrific book that you’ve written.

MARY-FRANCES O’CONNOR: Thank you so much, Ira, for bringing this conversation to the radio.

IRA FLATOW: Mary-Frances O’Connor, author of The Grieving Brain. She’s based in Tucson. And if you’re interested in learning more about this topic, you can read an excerpt from the book on our website, sciencefriday.com/grievingbrain.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.