Uncovering A Colorado Apple Mystery

17:37 minutes

In the late 1800, Colorado was one of the top apple growing states, but the industry was wiped out by drought and the creation of the red delicious apple in Washington state. But even today, apple trees can still be found throughout the area. Plant ecologist Katharine Suding created the Boulder Apple Tree Project to map out the historic orchards. She talks about Boulder’s historic orchards, some of the heirloom varieties like the Surprise and Arkansas Black, and a surprising connection to a hit Hollywood franchise. Plus, cider maker Daniel Haykin talks about how he uses the information from the Boulder Apple Tree Project combined with sugar, yeast and apples to make the bubbly beverage.

Katharine Suding is the leader and founder of the Boulder Apple Tree Project and a professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado Boulder in Boulder, Colorado.

Dan Haykin is founder and cidermaker at Haykin Family Cider in Aurora, Colorado.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow coming to you from the Chautauqua Auditorium in Boulder, Colorado.

[CHEERING AND APPLAUSE]

When you drive into Boulder you are struck by the landscape. It is a visual feast. There are these snow capped Rocky Mountains, the awesome backdrop of Chautauqua Park, the flat irons, those jagged sandstone structures that rise up from the horizon, of course the iconic symbol of this landscape.

But if you were in Boulder in the 19th century, you would have noticed something else, too, apple orchards. Colorado was one of the top apple growing states in the late 1800s. The orchards disappeared. But if you look around, you can still find apple trees here and there. Where did all the orchards go? What varieties are here? And if you have apples, well you should probably make something to drink out of them too, like apple cider.

My next guests are studying all of these things. Katharine Suding is the leader and founder of the Boulder Apple Tree Project and a Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado Boulder. Welcome to Science Friday.

KATHARINE SUDING: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Daniel Haykin is Founder and Cider Maker at Haykin Family cider in Aurora, Colorado. Welcome to Science Friday.

[APPLAUSE]

So, Katharine, tell me about this. I had no idea that Colorado used to be filled with apple orchards.

KATHARINE SUDING: Yeah, so I guess we all like apples, most of us like apples. But in the 1800s people really, really liked apples. There were reviews and ratings of different varieties, almost like how we would review Hollywood movies.

IRA FLATOW: Really?

KATHARINE SUDING: So it was thing. Yeah. And there was about 1,400 varieties of apples planted across the United States at the turn of the century. So it was a passion of Americans, for sure.

And so when settlers were moving from the east across the Plains to make a new life in the West and in Colorado and in Boulder, they wanted to bring the apples with them. They were super important. So they would bring paper wrapped saplings of these trees in their wagons across the West or seeds to plant in their new homes. So it’s a grand experiment. People were pretty skeptical growing at this high elevation, harsh climate, really dry, cold. There was a lot of failures at first, but then they were pretty successful.

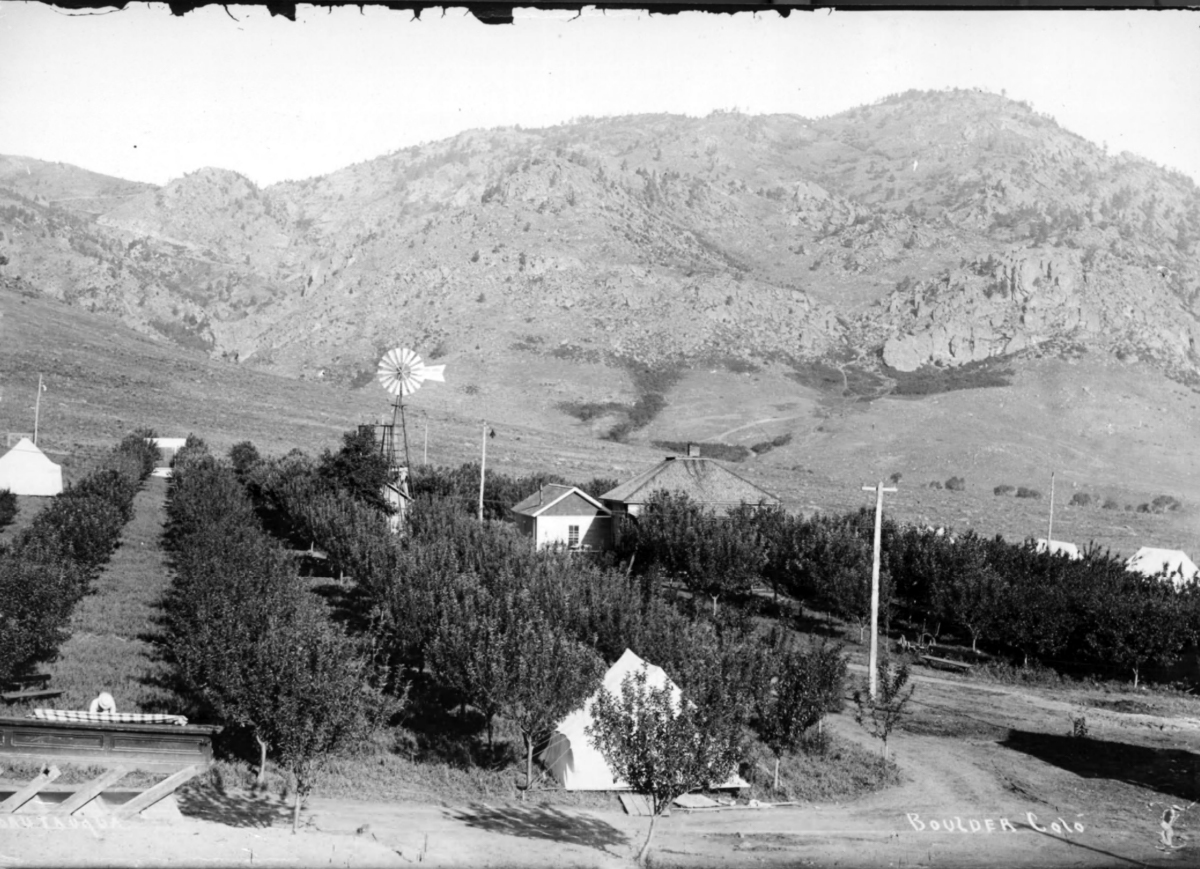

By the turn of the century, there were a lot of successful orchards in the Front Range, as well as in southern Colorado and in the Western portion of Colorado, where we are right now. In fact, Chautauqua was once a apple orchard, before it was bought by the city of Boulder and turned into Chautauqua.

IRA FLATOW: So what happened to all the apple trees?

KATHARINE SUDING: So I guess a couple things. First of all, by the turn of the century, it was clear that Colorado was actually a great place to grow apples. The high altitude made the apple’s really sweet and intense, and so it was really just an exceptional apple. And apples from Colorado were winning medals at the World’s Fair in St. Lewis in 1914. By the 20s, we have some pretty good data that there is about 400 varieties grown here and about 1 and 1/2 million apples in Colorado.

And then kind of a couple things just hit around that time. The first thing was the Red Delicious. It was named delicious and it was heavily marketed across the whole United States for this was the apple that everyone should plant everywhere. And that didn’t work out too well for Colorado because it doesn’t do very well in Colorado. But people were starting to plant this apple, that really was then hit by disease in our climate and so it was declining then.

And then in 1920 was prohibition. And if you look at all the apples and why the settlers were bringing apples here, they were bringing them a lot for hard cider. A little bit of fresh apples– so about a quarter of the apples that were planted around here were for eating and then 3/4 were mostly cider varieties.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Now you started the Boulder Apple Tree Project after you found an apple tree in your yard, right? How do you define an apple tree, first, aside from looking for the apples? Is there a way to identify an apple– hey, I have one in my yard. How did you discover that?

KATHARINE SUDING: Well you pretty much know. There’s a lot of reasons why you can identify an apple as a tree, in terms of the leaves and the bark and the fruit, obviously. Identifying the variety of that apple, super, super hard. First of all, we go to the tree, right, we sample it, we record characteristics. And I guess it, probably for people who know apples just from their grocery stores, probably seems easy to describe the apples, you know different colors.

But actually apples, that characteristic of even the fruit, is amazingly diverse. So there’s apples with skin like sandpaper, ones that are super shiny. There’s ones that are shaped like a misshappen potato, ones that are perfectly round, ones that are the size of a cherry, ones that are as big or bigger than a grapefruit.

IRA FLATOW: But if you don’t believe or we actually brought some slides here to show you. I’m going to have you narrate. I’m going to bring up each slide. The first one is a Crabapple. Describe this apple that we’re looking at.

KATHARINE SUDING: Yeah, so there’s about 12 varieties of Crabapples that were grown in orchards around Colorado. And these are not Crabapples like the ones in your yard. They are ones about the size of a golf ball. And they actually are well-known for their disease resistance, as well as they have the cider trifecta. They’re sweet, they’re acid, and they have tannins in them. So they have all the three flavors, all in one single apple.

And these guys got hit hard with prohibition because if you bite one of these, you really don’t want to eat it. But they are perfect, perfect for making cider. And so there are these kind even in the grounds in Chautauqua now that have survived.

IRA FLATOW: Let me go on to the second apple I want to show you. I hear that this one is your favorite. The Surprise– the Surprise apple.

KATHARINE SUDING: (LAUGHING) Yeah, so–

IRA FLATOW: Because?

KATHARINE SUDING: Surprise! So you look at it, it’s just this yellow apple, it looks maybe a little blush. You bite into it and, instead of being red on the skin, the flesh of the apple itself is red. So the anthocyanins that are sometimes on the skin of apples, this is in the flesh.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

KATHARINE SUDING: And so they’re people working on breeding this because they think this could be a sweet sour, like the Sour Patch Kid, equivalent apple for kids. And they are nutritious because they have the antioxidants in the tissue and not the skin.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Next Apple has a familiar name. It’s called Rambo.

KATHARINE SUDING: Yeah, I like this one, too.

IRA FLATOW: Rambo.

KATHARINE SUDING: And this one, there’s a lot of these around Boulder. So Rambo was a variety that was brought over by the Swedish explorers in the 1600s. They brought some seeds from Sweden with them, they planted them in new Sweden, which is in Delaware, and this tree grew. And so they called it Rambo after the name of an explorer. Super, super popular in the 16 and 1700s.

And David Morrell, who is the author of the books with Rambo as the main character, actually tasted this apple, his wife brought some from a roadside stand, and named his character after it because it was so bold and tart.

[CHEERING AND APPLAUSE]

And I like it, too. You should try it.

IRA FLATOW: Who would have ever thunk Rambo is named after an apple. OK. How about them apples, folks? Isn’t that great?

[APPLAUSE]

Now we’ve talked a lot about cider, let’s get into cider with Dan Haykin. You’re a cider maker. We’re talking about the boozy kind. The cider apples are different than the ones that we eat, right, that you make into cider?

DANIEL HAYKIN: Yeah. In traditional cider making cultures there are apples for eating and apples for cider production. Overwhelmingly cider apples have a lot of tannin. So fresh they’re rough and astringent. But fermented they have body and dimension, just like a red wine would.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you you talk like a winemaker. Dimension and body.

DANIEL HAYKIN: Cider is wine. It’s just wine made with apples instead of grapes.

IRA FLATOW: Ah! Now I understand you have an interesting way of collecting the apples that you need to make your cider.

DANIEL HAYKIN: So one of the many wonderful things about apple trees is they’re perfectly capable of taking care of themselves, even when humans ignore them. So in season I look for the best fruit. And I don’t really care whether that comes from a farm stand or the side of the road. So I drive around with a huge tarp and 50 Home Depot buckets and sugar testing device called a refractometer, and I pull over a lot. And when I find a really cool tree, I have a 20-foot pole and I shake the tree and apples come raining down.

IRA FLATOW: So you’re foraging, you’re foraging for apples.

DANIEL HAYKIN: Quite literally, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Do you go into people’s properties? Do you get invited in? Do you ask, hey, you got a great apple tree. I want to shake your tree over there.

DANIEL HAYKIN: I have trespassed before, but I didn’t know I was doing it at the time.

IRA FLATOW: OK. What qualities? Are there special apples you’ll reject? Or what qualities are you looking for?

DANIEL HAYKIN: So similar qualities to what you would look for in a wine grape, aroma, flavor, acidity, sugar content, and tannin.

IRA FLATOW: I noticed you nodding your head as Katharine was going through her favorite apples. Do you ever use some of the apples we were looking at?

DANIEL HAYKIN: Yes. Indeed, all of the ones she mentioned I’ve used.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. So it involves fermentation, right?

DANIEL HAYKIN: Correct.

IRA FLATOW: But you don’t brew the apples.

DANIEL HAYKIN: No. No, there’s no heating of any kind. Just two ingredients, apples and yeast. The yeast is a single cell organism, it’s a type of fungus, and it converts the sugar into alcohol, carbon dioxide, and heat. First, you have to press the fruit which is complicated because unlike a grape apples are very hard so you can’t just squeeze them and juice comes out.

So first you have to grind them. So you have to figure out how to create a whole lot of very coarse applesauce. That gets pumped into our press and we press it directly into wine tanks. We either will use cultured yeast, which is basically a single organism that’s been propagated so it’s consistent and repeatable. And sometimes we use ambient yeast, yeast that’s all around us, that ferments–

IRA FLATOW: Just leave it open to the air and the yeast comes in, like baking bread, that way?

DANIEL HAYKIN: It’s not that easy, but yeah, that’s the general concept. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. We’re talking about apples in Colorado with Daniel Haykin, who is making cider. And you have some samples here of some cider.

DANIEL HAYKIN: Correct. Yeah, I brought two ciders. The apples, both of them were grown in this region, so on the east side of the Rocky Mountains. Supposedly this is a very tough region to grow fruit. And it is for eating purposes, but for fermentation and drinking, we think this is one of the best growing regions on Earth. And hopefully these two ciders showcase that.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s do a little taste testing.

DANIEL HAYKIN: Sure.

IRA FLATOW: I have two glasses of cider here, two different bottles labeled number one, number two. So do you, Katharine, right? So what are we tasting?

DANIEL HAYKIN: So number one is made out of an apple called the Akani apple. It’s a Japanese apple that’s also known as Tokyo Rose because it has a very floral quality to it. Fermented, that floral quality follows through. So it’s in effect dry, but it feels sweet because it’s so fruity and has such a distinct aroma to it.

IRA FLATOW: It does. It smells like an apple. And how long does it take to make that from the time you squeeze the apple?

DANIEL HAYKIN: Our fermentation process is usually around three months. And then maturation can be as much as four to six months before we release it. So from the time we harvest an apple to the time a customer is drinking it is usually 9 or 10 months.

IRA FLATOW: Let me look at the second glass. What is the second?

DANIEL HAYKIN: So the second glass is made out of crabapples that were foraged within a mile of where we’re sitting right now. So these are Boulder crabapples from 100 plus year old trees. These apples have a lot of tannin. So when you take a sip it’ll remind you a red wine.

IRA FLATOW: I was just about to say that. This is absolutely delicious.

DANIEL HAYKIN: Good. So the flavor profile here, instead of just light, bright, and refreshing, now you have much deeper flavors and tones. Caramel comes out, automonal flavors, like freshly raked leaves. It’s a much bigger–

IRA FLATOW: I didn’t get that. I don’t think I got– I didn’t get the raked leaves. If you’re foraging for the apples, how can you repeat getting the same wine again, if it’s by luck of where you can shake the tree at?

DANIEL HAYKIN: You can’t. And that’s why every wine should have a vintage year on it, because you can’t ever recreate the same year. The weather changes, everything changes.

IRA FLATOW: Is there any effort to create artisanal apples here now in Colorado, if you have such great apples resurrecting the apple industry?

KATHARINE SUDING: I would love that. I would love to first try to save these special varieties. And save them in community orchards that don’t just try to just grow one of these commercial varieties that doesn’t really taste good. I mean, I don’t know, Red Delicious, sweet, sawdust, kind of flavor.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: You’ll get the mail, not me. Or, we’re hoping.

DANIEL HAYKIN: So the important thing, if Professor Suding doesn’t save these apple trees, there literally could be one out there and that’s it. And it’s 100 years old and if it gets struck by lightning, it’s gone forever. So the work that she’s doing, there’s a clock running right now and it’ll run out on many of these species. And then they’ll be gone forever. And she’s saving them for us, for future generations. It’s huge work.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. I want to thank both of you for, this is really interesting, for taking time to be with us today. Katharine Suding is Leader and Founder of the Boulder Apple Tree Project and Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Colorado in Boulder. And Daniel Haykin is Founder and Cider Maker at the Haykin Family Cider in Aurora, Colorado. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

[APPLAUSE]

And let’s give one last round of applause for [INAUDIBLE], who is going to play us out tonight. Come on back.

[APPLAUSE]

[MUSIC PLAYING]

That’s about all the time we have. Our heartfelt thanks to Neil Best, Robert [INAUDIBLE], and Ashley Jeffcoat, and all the great folks at KUNC for hosting us. Thanks to all of you. Also thanks to Buddy Baker and all the wonderful folks at the Chautauqua Auditorium for making this wonderful evening possible. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

And thanks to all our Science Friday staff. It takes a lot of people behind the scenes to run this ship.

[APPLAUSE]

In Boulder, Colorado. I’m Ira Flatow. Drive safely everybody. Have a good night.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.