How GPS Found Its Way

08:36 minutes

In the early 1970s, the idea for a satellite-based modern navigation system was controversial in the United States Air Force. Many in leadership didn’t want anything to do with the project that would become our now-ubiquitous GPS—they thought the money was better spent on putting more planes in the air.

Engineer and former Air Force colonel Brad Parkinson directed the GPS project during that fragile time, and made countless appeals in Washington to get it approved and keep it approved in the years it took to perfect the technology. He’s now receiving the 2016 Marconi Prize for his dedication to ensuring that the first GPS satellites got off the ground. He shares the story of the difficult birth of GPS.

Bradford (Brad) Parkinson is Emeritus Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford University School of Engineering in Stanford, California.

IRA FLATOW: This is “Science Friday.” I’m am Ira Flatow. The US Navy has announced plans to teach sailors how to navigate with ancient technology, the sextant and the stars. So why in this age of GPS would the Navy resurrect celestial navigation? Because GPS is highly vulnerable to jamming. Imagine a world without GPS. It would literally come to a standstill.

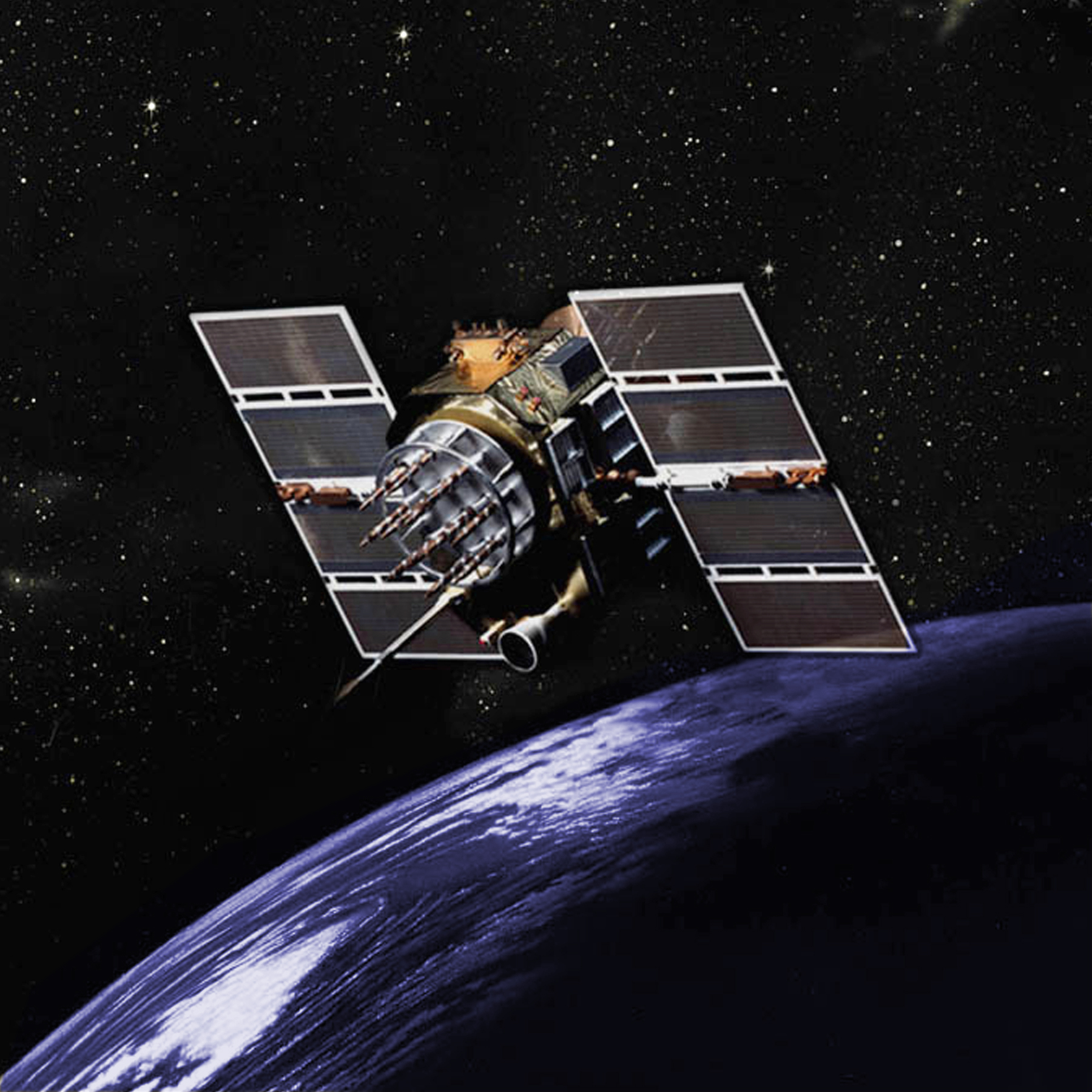

And if you heard our conversation with author Greg Milner a couple weeks ago, you have some sense of the unexpected ways GPS has changed our lives. From urban transit to sugar beet farming. That’s why it’s hard to believe that GPS was an invention that first went unwanted. In the early 1970s the Air Force was working on a satellite assisted navigation system. But the military brats felt the resources would be better spent on building more airplanes.

My guest, my next guest, was a tireless champion of the early GPS project. And is receiving the 2016 Marconi Prize for his work to steer GPS from an under appreciated idea to a crucial part of our lives. Brad Parkinson is a professor emeritus of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford University, School of Engineering. A former Air Force colonel, he directed the US Air Force project to develop GPS. Professor Parkinson welcome to Science Friday, nice to have you.

BRAD PARKINSON: Thank you so much. I enjoy your program and I enjoy being here.

IRA FLATOW: Well, thank you. Remind us what kind of navigation system we had before GPS.

BRAD PARKINSON: Well, there were a vast number of navigation systems of course for the Navy. There was a reliance to the sextant. We had a system, a radio nav system called Randy that was quite local. The Navy had a periodic navigation system called Transit. But none of these were continuous, three dimensional, highly accurate systems. And as a result, they all had really serious shortcomings.

IRA FLATOW: So tell us the story. You got involved in GPS with the Air Force. It wasn’t guaranteed that it would go anywhere. What was the thinking here?

BRAD PARKINSON: Well it was almost guaranteed that it wouldn’t go anywhere because it had been floundering for four or five years. And I got tabbed to go into a position as the leader of a struggling operation. And I had the right background, I had a background in space mechanics and in inertial navigation. And I also went to the Naval Academy and knew how to use the sextant.

So I appreciated what it could do but unfortunately not only was there skepticism of what it could do, there was skepticism on whether that was where the money should be spent. And it was a constant struggle, even after we had reformulated the whole system. To try to get particularly the Air Force to agree that this is what they ought to do.

IRA FLATOW: So how eventually did you work your magic to get it approved?

BRAD PARKINSON: Well first of all, if you’re running the gauntlet like that, you cannot afford to make any serious mistakes. And I was surrounded by some wonderful people. The boss that I worked for, a three star general, encouraged me to hire the very, very best from within the Air Force. These were bright young officers with Masters and PhD’s.

But the other ingredient, which I think was equally important or perhaps even more important, was that there was a high ranking civil person in the office of the Secretary of Defense, a Deputy Secretary of Defense, who took a personal shine to this program. He came down, I spent about three hours with him one afternoon in Los Angeles. He apparently became convinced and he defended me against all comers. He said–

IRA FLATOW: Who was that?

BRAD PARKINSON: That was a Doctor Mal Currie. And he in essence said, Air Force, let the young colonel go off and build the system. He told them, just wait and see. It’s going to do what he says.

IRA FLATOW: And so tell us about– I’m sorry, go ahead.

BRAD PARKINSON: And it did.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. What were the technical problems you needed to overcome before these first satellites could be launched?

BRAD PARKINSON: Well, first of all, you had to have a concept. And the concept was to use four satellites. Your scientific listeners will all realize that three ranges determine a point, but it turns out you needed a point in four dimensional space because your local clock was to crude to get down to well, now millimeters.

But– so, having a good space clock, a good concept, the four satellites, and a good signal structure– this is a little esoteric– but we had a signal structure called CDMA, code division multiple access. And this allowed all of the signals to be broadcast on exactly the same frequency. And it turns out that locks out a lot of biases and has led to millimeter level accuracies for geodesy.

IRA FLATOW: You know what I also found interesting is you worked from the beginning to ensure that the system would be open to civilians. You found that important.

BRAD PARKINSON: Absolutely. And there are a lot of misconceptions about that. You hear people saying, well it was a military system and eventually made a civil system. That was not true.

When I testified before Congress back about 1975, I said this is a combination military civil system. We originally thought the civils wouldn’t get quite the military accuracy, but it turns out there are a lot of creative people out there. And in no time at all, they got close to the military accuracy, briefly the military tried to mess that up but then realized there was no point in it.

And since 2002, President Clinton has guaranteed that that will not– those variations in the signal will not happen again. And as a matter of fact, the new satellites don’t even have the capability.

IRA FLATOW: We hear stories now about how easily you can buy a little object that will jam GPS from people who don’t want to know when their car where they’re going. But it’s now interfering with the GPS systems at airports, for example. Do you see this is as a threat now that needs to be thought about?

BRAD PARKINSON: Oh I absolutely do. And I think that there are some things coming along in technology that will help. We can build a tougher form of receiver, but it’s expensive.

But at the same time, we have right now only one civil signal. And that comes from the US GPS. Within about five years, we’re going to have 17 different signals, from not just GPS but from the Europeans Galileo, which emulate to us from the Russians’ Glonass, which we can check for integrity. And even the Chinese are putting up a system and I didn’t count that in those 17 signals.

So the point is that diversity helps but I personally think a prudent person still does some cross checks.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah because you know, it could be used as a weapon, the jamming. Could it not? If you take down the GPS system you take down the stock market, you’ll take down air travel, just about everything we use.

BRAD PARKINSON: There is a lot at stake. And fortunately I’ve devoted most of my recent life to ideas on how one toughens a GPS receiver. And for safety or economic critical applications, we know how to make it very, very jam resistant. But unfortunately those ideas have not been deployed yet.

IRA FLATOW: Because?

BRAD PARKINSON: There is another threat I should add.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

BRAD PARKINSON: The FCC is contemplating putting very high powered broadband transmitters in the adjacent band. And if that were to happen, the chances are a lot of users who rely on it now, are going to be taken out.

IRA FLATOW: Because of the spill over into the GPS band. That could happen.

BRAD PARKINSON: Precisely. Exactly.

IRA FLATOW: So we should be aware of that. We’ll talk more about– I want to congratulate you on the Marconi Prize, winning the Marconi Prize this year. And thank you for all your contribution and your hard work.

BRAD PARKINSON: Well, thank you for this opportunity to talk about it, and I wish you a good day.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Brad Parkinson, professor emeritus of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford. He directed the Air Force project to develop the GPS and a retired colonel.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.