How Hurricane Irma Could Affect Florida’s Endangered Species

12:07 minutes

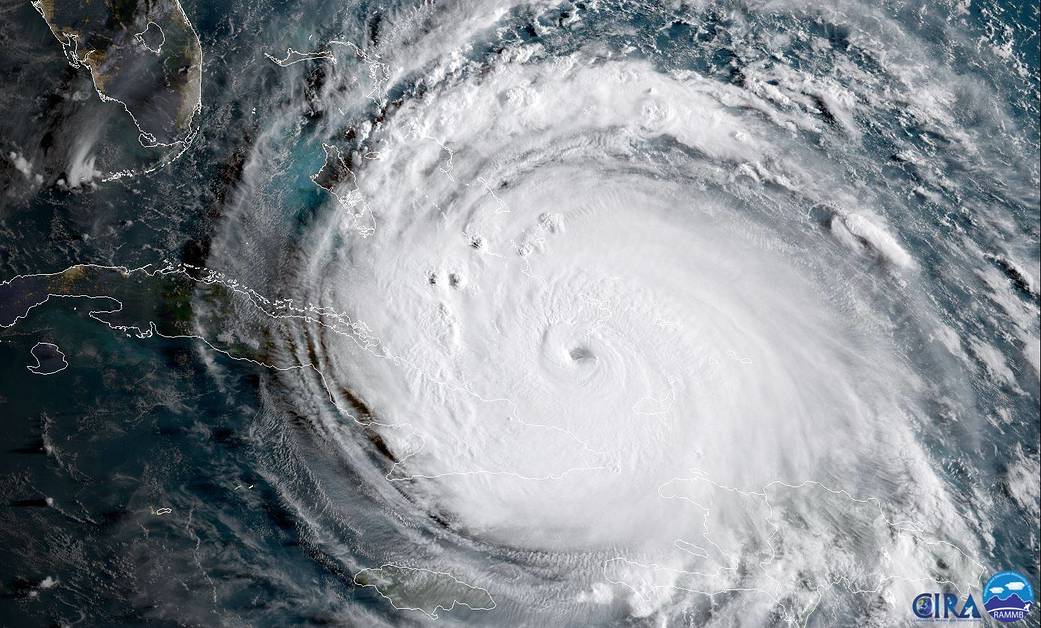

Barely two weeks after Hurricane Harvey unleashed a devastating amount of rain on Houston, Texas, Hurricane Irma ripped through the state of Florida. This week, the city of Jacksonville is reeling from record-setting flooding, and millions of people are without power, which may not be restored for days and possibly weeks.

[Hurricane Harvey is the beginning of a new normal.]

Irma’s category 5 winds and storm surge hit the Florida Keys especially hard. Residents who evacuated the islands are still waiting for the highway to reopen so they can return to what is left of their homes and communities.

And just like Florida residents, biologists will soon return to the Keys to reckon with the destruction Irma has left in its wake. In addition to people, the delicate ecosystem is home to many threatened and endangered species, like the magnificent frigatebird, Miami blue butterfly, and the pine key deer. Wildlife researchers, including Dr. Danielle Ogurcak at the Institute of Water and the Environment at Florida International University, and Dr. Kenneth Meyer, Executive Director of the Avian Research and Conservation Institute, are anxious to know their fate.

Danielle Ogurcak is a postdoctoral associate in the Institute of Water and the Environment at Florida International University in Miami, Florida.

Jaret Daniels is Associate Curator and Program Director at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity of the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, Florida.

Kenneth Meyer is the Executive Director of the Avian Research and Conservation Institute and Courtesy Associate Professor at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. A little bit later, a look back at the Cassini Mission, the end of the mission to Saturn as the Cassini made its fateful and final plunge into that gas giant.

But first, barely two weeks after Hurricane Harvey unleashed devastating rain on Texas, Hurricane Irma’s winds ripped through the Virgin Islands and Florida. Irma’s category 5 winds and storm surge hit the Florida Keys especially hard. Residents who evacuated the islands are still waiting for the highway to reopen so that they can return to what is left of their homes and start to rebuild.

And along with Florida’s residents, biologists will soon return to the Keys but with a slightly different purpose. The Keys’ delicate ecosystem is home to not only people but many threatened and endangered species like the magnificent frigatebird, the Miami blue butterfly, and the Pine Key deer. Wildlife researchers, like my next guest, are eager to know their fate.

Danielle Ogurcak is a post-doctoral associate at the Institute of Water and the Environment at Florida International University in Miami, Florida. Welcome to Science Friday.

DANIELLE OGURCAK: Thank you. I’m really happy to be here.

IRA FLATOW: It’s nice to have you, Danielle. Kenneth Meyer is executive director of the Avian Research and Conservation Institute in Gainesville, Florida. Welcome, Kenneth.

KENNETH MEYER: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask you, Danielle, first, how long until you can get back to the Keys, and what do you expect to see when you get there?

DANIELLE OGURCAK: At this point, we’re not sure on the timeline. I have been in contact with the refuge biologist at the Key Deer Refuge, and we’re hoping within a couple of weeks. I believe what we’re going to see is, I’ve taken a glimpse at what Noah already has some imagery of after the hurricane. And what we see right now is a mix of downed trees within the forest. But it’s definitely still plenty of standing trees in the forest.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me about something called the freshwater lens and why that is important.

DANIELLE OGURCAK: Well, the Florida Keys, while we have a pine land in the lower Florida Keys and why we have Key deer is because there’s fresh water in the lower Keys. And that fresh water is there because of the unique geology of the lower Keys, the Miami oolite, the same surficial rock that we have in South Florida that is where we get our water from the Biscayne Aquifer outcrops in the lower Keys.

And in there fresh water essentially, it’s porous enough. It stays in there and essentially floats on top of the underlying saline water, but it’s completely rain driven. So it’s important how much rain we get.

IRA FLATOW: And is there any way to pump the salt water out to replace the fresh water by hand? I imagine that’s not possible.

DANIELLE OGURCAK: No, it’s not. And actually we’re not sure how quickly it does recover. It really is a balance between how much rain we get with the storm, how much subsequent rain we get after this into the next season.

After Hurricane Wilma there were some really devastating effects in that there was very little rain associated with that storm, only two inches. Whereas, according to the weather station at the north end of Big Pine, they received about 12 inches as Irma came through.

After the storm surge came through, there was a drought. And what we saw was a series of prolonged mortality where pine trees that need fresh water, that are the foundation species of that ecosystem started to yellow. And over years, probably lost about 30% of all the pine trees there.

And on some islands where, on Cudjoe Island out there was an ice stand that essentially there’s just some relict pine trees left at this point. And they’re likely not coming back.

IRA FLATOW: Kenneth, unlike Danielle, you don’t have to wait to find out what happened to the endangered birds there that you study. You have data about them coming in right now, correct?

KENNETH MEYER: That’s true. We have 35 individuals, seven different species that we’re tracking by various means, satellites and just hand-held radio receivers. And we’ve been tracking these birds, some of them for several years, and some of them just the last few weeks.

But we have a good idea of pretreatment movements in effect, what was going on before the storm. And so we get to answer the question, what are these birds doing? How well do they survive?

IRA FLATOW: Where do the birds go during the hurricane? Give me an idea of a bird or two, what happens to them?

KENNETH MEYER: Well, sea birds, some of which we studied, [INAUDIBLE] birds would be an example, they can fly over the ocean for days and days and days. And what the single bird that we’re tracking at the moment did last year in Hurricane Hermine, it did exactly the same thing a few days ago.

It’s been living on the west coast of Florida around Crystal River. And it just takes a big loop out over the Gulf of Mexico as the storm approaches and comes back as the weather calms, done exactly the same thing. But really, that’s not the common theme.

The other species that we’re tracking like reddish egrets, white-crowned pigeons, swallow-tailed kites, what they do, if they’re not in the process of migrating, is they just hunker down. We have five reddish egrets we’re tracking on Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge on Sanibel, which is Near Fort Myers north of the Keys, but was heavily hit. And those birds remained right in place where they’ve been for years, literally. And they seem to come out a little bit in the open and then they go back into the dense mangrove. So they’re using the very dense mangrove forest for cover.

White-crowned pigeon, same thing. They’re actually in the process of migrating out to the Caribbean after their breeding season. One bird that we still had out on Big Pine Key, right where Danielle was talking about, sat tight, didn’t migrate yet. And it was there, alive, after the storm. We can tell from the data and how it’s moving.

Another bird had already moved onto Cuba right in front of where the storm was headed. And that bird also sat tight.

So that’s what we’ve seen in the past with other species. And that’s what we see with these and more species. And it really suggests that these birds are supremely well adapted to deal with these natural extreme events. They’re extraordinarily resilient. But here I would just like to remind everybody that the birds were studying, along with snail kites and short-tailed hawks, those that we’ve tagged, American kestrels, all birds that are looking at right now in relation to the hurricane, they’re all considered imperiled, if not formally listed as endangered.

So they can handle something like Hurricane Irma and come out right where they started in the same place and come out alive. And yet, they’re declining because of things that we are doing in the longer term to habitat, to native vegetation, to their food sources. I think that’s a huge lesson for us that if we give these birds at most half a chance, they can survive. They can reproduce well. They can maintain their populations.

But the things that we are doing, they’re so insidious because they’re gradual. And we don’t see that exciting change rapidly, that exciting bad change like you see with a hurricane. And I think that’s dangerous.

IRA FLATOW: No, that’s not good to hear. We also spoke with Dr. Jaret Daniels at the Florida Museum of Natural History about what happened to the species of butterflies that he studies.

JARET DANIELS: We’re primarily worried about the impact of storm surge because these are low-lying islands, only a few feet above sea level. And it also depends on the extent of the damage and what life stage these butterflies were in when Irma hit.

In the case of Shasta swallowtails, they were in their pupil form, and they are anchored with silk to the vegetation or they pupate low within the limestone crevices. And so we feel that butterfly probably survived Irma in a much better situation.

The Miami blue is a butterfly that has a continuous generation, and we don’t know what life stage it was when Irma hit. But if it was caterpillars or adult butterflies, those are probably halfway to Cuba or the mainland right now and not in pretty good shape.

Fortuitously, both of those species we have in captivity here at the University of Florida in Gainesville. So if they are severely impacted in the wild, we have stock here that is safe and that we’ll use to try to repopulate those areas in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Very interesting. Danielle, in the minute or so that we have left, we have seen huge devastation to the Virgin Islands that hasn’t gotten much coverage. But you’ve seen pictures of them. Are you familiar with how they might recover? And would you like to study them also?

DANIELLE OGURCAK: The Virgin Island is a beautiful place, that forest, and both dry and moist, tropical and subtropical forests. But being in the Caribbean, they are used to their disturbance adapted in many ways, the trees there. The biggest concern for me is two things in that they’re like many islands, there’s exotic plant species problems.

So if you disturb a large area after a storm, you have exotic plant species, the ability to kind of colonize first. So that’s something that would need to be watched, especially in areas that were just kind of like denuded of vegetation.

But in terms of the issues to the marine habitat, we have these really steep island on St. John, these essentially called guts that water will just flow down these during hurricanes and strong storms. And they can bring a lot of sediment. And that sediment will end up in the seagrass beds and in the coral reefs. And that’s something that the folks there will want to be monitoring after the storm.

IRA FLATOW: So this is really an opportunity for scientists all over Florida and the Caribbean to actually see what happens following a storm also.

DANIELLE OGURCAK: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Do we have a lot of data on that? I mean, have there been a lot of hurricanes as scientists have been going out over the years?

DANIELLE OGURCAK: Yes, there was a lot of work done after Hurricane Hugo in 1989. And that’s how we know that the hardwood species can come back actually relatively quickly. They have the ability to, what’s called coppice or stump sprout from same individuals. So within several years, the forest can start to come back.

The same cannot be said for a pine forest that we have in South Florida. They don’t do that. They need to re-seed, have an appropriate place to germinate, and take the time to get to adulthood. And that’s why we worry even though there’s been many years of disturbance to this system and it’s recorded in the trees, an increased frequency of strong hurricanes is not going to be a good sign for regenerating pine forest.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much for talking with us, Danielle Ogurcak, post-doctoral associate at the Institute of Water and Environment at Florida International University in Miami.

Kenneth Meyer is executive director of the Avian Research and Conservation Institute in Gainesville, Florida.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.