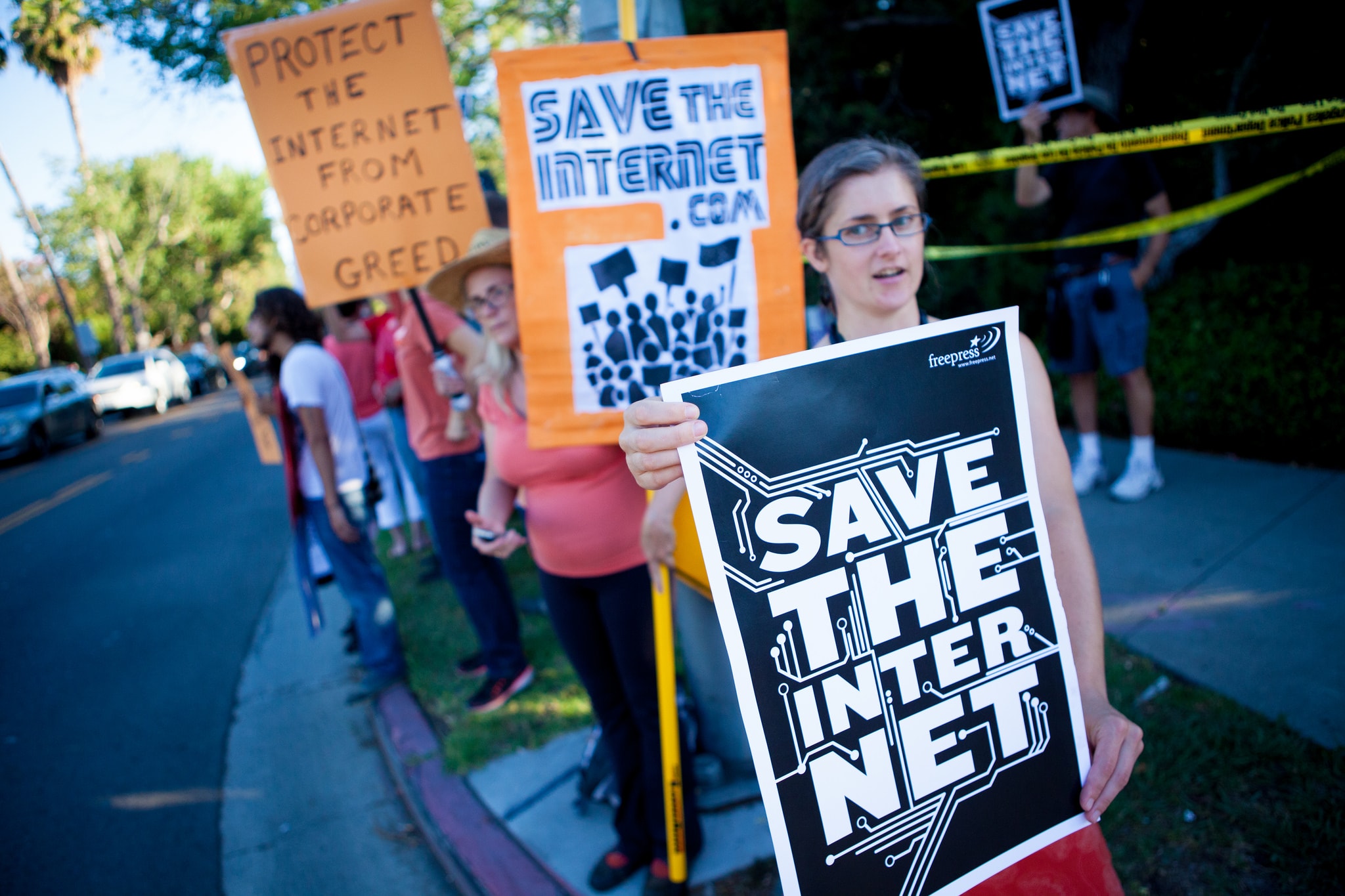

How Will Net Neutrality and Telecomm Fare Under the New Administration?

11:57 minutes

Two years ago, the Federal Communications Commission approved rules that would enforce “net neutrality,” which requires internet service providers to treat all data equally so as to avoid “fast lanes” for certain content. Ajit Pai, the newly appointed FCC Chairman, said in a 2015 interview that “net neutrality is a solution in search of a problem. I have yet to have anybody point out what the systemic failure is that requires the FCC to adopt Title II or any neutrality regulations.”

Susan Crawford of Harvard Law School and Jon Brodkin, a tech policy reporter for Ars Technica, discuss how the open internet, broadband expansion, and security regulations will fare under the new administration.

Jon Brodkin is a Senior IT Reporter for Ars Technica. He’s based in Massachusetts.

Susan Crawford is author of Captive Audience: The Telecom Industry and Monopoly Power in the New Gilded Age (Yale University Press, 2013), co-author of The Responsive City: Engaging Communities Through Data-Smart Governance (Jossey Bass, 2014), and visiting professor at Harvard Law School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, we debate the price we pay for so-called free internet services like Gmail and Facebook. I’ll give you a hint. It’s your privacy.

But first, one of the big topics of debate for the Federal Communications Commission is the idea of net neutrality, the idea that all content on the internet should be treated equally by providers. After a long debate and public comments, the FCC passed rules to enforce net neutrality back in 2015. Ajit Pai, the newly appointed FCC chairman, has a different viewpoint when it comes to net neutrality.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

AJIT PAI: And I once said that net neutrality is a solution in search of a problem. I mean, there are all these different broadband policies we could be focusing on to bring greater competition to the American marketplace, which ironically, would solve the very problem that net neutrality advocates purport to care about.

[END PLAYBACK]

IRA FLATOW: So what policies might the FCC focus on? What might these policies mean for you if you want to stream video from an app as opposed to, let’s say, your cable box? And will other telecom issues like broadband expansion be regulated? Well, we wanted to know the answers to these. We invited Ajit Pai onto our program, and we were told he was unavailable.

But my next guests are here. Susan Crawford is a law professor and co-director of the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard. John Brodkin is senior IT reporter for Ars Technica. He’s based out of Marlboro, Massachusetts, and joins us via Skype. Welcome to Science Friday.

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Hey, thanks.

JOHN BRODKIN: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: It’s good to have you. Susan, can you give us a brief explanation of what net neutrality is and how it was looked at by 2015?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Yeah, well, basically, about 10 years ago, the FCC said they wouldn’t have any legal authority over high speed internet access providers. People wanted to make sure that those providers treated content trying to reach subscribers equally. And the FCC wanted to make sure it had legal authority over those providers. So back in 2015, the FCC essentially relabeled high speed internet access as a utility and along the way, adopted some rules about how a provider should treat content.

IRA FLATOW: And those rules basically said there is no what? No priority for traffic?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: No throttling, no blocking. But really, the most important move was just to say, we have legal authority. And it’s that that Ajit Pai wants to get rid of, even more than the rules. He wants to make sure that these carriers can basically do whatever they want.

IRA FLATOW: Is that what he basically said in the little bit of clip that we played?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Well, he’s not saying that directly. He said that elsewhere. In that little clip, he’s saying, I think net neutrality doesn’t really exist as a problem. What does exist as a problem is a stagnant, uncompetitive market completely controlled by a series of local monopolies in the United States, which is posing huge problems for the country’s destiny. And that, he’s not willing to comment on.

IRA FLATOW: He’s not.

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Mm-mm.

IRA FLATOW: John, but part of the FCC’s net neutrality rules was to reclassify the internet as a utility, like how the phone companies work, a Title II classification that Susan was talking about. Pai has said, I favor an open internet, and I opposed Title II. Does that mean that it is unregulated?

JOHN BRODKIN: I mean, it’s hard to say. I don’t think unregulated entirely is what he wants. But he wants to eliminate the Title II classification, which in general, requires internet providers to be just and reasonable in their practices and rates. And by getting rid of that, that would also get rid of the net neutrality rules.

In general, he said that he thinks internet service providers should be unfettered by regulation so they can spend their time or money in investing in their networks instead of following rules. So I mean, when he says he wants an open internet– I mean, he hasn’t actually said if he would support any type of net neutrality rules. So it seems like he wants the internet providers to be free from regulation. And in that sense, he thinks that will create a lot of competition that will preserve the open internet.

IRA FLATOW: But in allowing everybody to be the Wild West of providers and in competition, which people like, would that not force out smaller providers who may not have as many customers in their database?

JOHN BRODKIN: I’m not sure about that. I mean, I think the biggest issue is trying to make it economically viable for smaller providers to compete against the big ones. I don’t know if getting rid of net neutrality prevents that. But it’s almost like a separate issue.

Actually, I think Chairman Pai made one good point, that if you had a lot of competition, you wouldn’t necessarily need net neutrality rules because then the marketplace would decide. But right now, most people only have, at most, one choice of high speed broadband provider. So if they could do something that would actually improve competition in cities and towns, then that would be a big improvement, even if they, at the same time, got rid of net neutrality rules. But it’s not really clear how they would achieve that.

IRA FLATOW: Susan, what’s your comment on it?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Yeah, I agree with John. Actually, it’s clear that Pai wants to get rid of Title II labeling, which would, essentially, get rid of any legal authority over high speed internet access providers because twice, courts found that the FCC trying to reach them using other parts of the Telecommunications Act wouldn’t work, wouldn’t stand. And so what we’re going to be left with is this series of local monopolies. And Pai seems very happy to just let that sit. He’s saying we’ll see more competition. It’s extremely unlikely. We have a very broken marketplace in the United States. And absent government intervention, there’s no reason that would change. There’s no real competition to the local cable actor in most American places.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I know in my town, I can only get one, possibly two cable providers. Others are kept out.

SUSAN CRAWFORD: That’s right. Even though that’s been illegal for a couple of decades now, as a matter of fact, in every town, it’s usually one big monopoly provider, and that’s it. So they’re not under any pressure from either competition or oversight to upgrade networks to fiber, to lower prices. Look, they’re not acting nefariously. It’s just not in their interest to invest, to support economic growth and social justice, which is what we need from infrastructure. Most other infrastructure in America is not controlled by private parties.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm, the FCC has recently expanded the Lifeline Program, which gives subsidies to low income families for phone and broadband services. And Pai reversed that, John. What is the reason for that?

JOHN BRODKIN: Well, he is concerned about fraud and waste in the program. And he doesn’t want any expansion until the FCC comes up with a more expansive system to prevent internet providers from illicitly gaining subsidies that they’re not supposed to get. So what happened was there were nine providers that were approved under a new program that lets them offer subsidized broadband throughout the country instead of going through a more cumbersome process where they have to apply to each state to offer services in that state. So for now, those nine companies can’t offer the subsidized service.

And in the FCC order, they said that customers of the one company of those nine that’s already offering subsidized services, they can try to find another provider. But at the same time, the FCC acknowledged that some of these poor people will have to pay $9.25 more a month if they can’t find an alternative provider.

IRA FLATOW: There was also a proposal to open up cable boxes to companies so that they could create apps or other alternatives. I mean, the big thing is now to stream video. And what do we think the new regulations or the new FCC chairman is going to do about allowing people to stream video from either their cable box or their app, from where they would like to?

JOHN BRODKIN: Well, he doesn’t really have any plans to do anything about that. He thinks the market will just take care of it. And there are cable companies that are offering their programming via apps on set-top boxes. What the old proposal under the Democrats would have done would have been to require every company like Comcast and Verizon and AT&T to make apps for something like the Apple TV or the Roku so that instead of renting a cable box each month, you could just watch on one of your other devices. So that proposal is what Pai has pulled off the table. And he hasn’t pushed any sort of alternative.

IRA FLATOW: Susan, the FCC recently stopped an investigation into a practice called zero rating. Can you explain what zero rating means and how it affects net neutrality?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Sure, the idea would be that someone like AT&T could treat content with which it has some kind of relationship, like maybe it owns content, or has a special contract with a content provider, to treat that content differently and not have it count against data caps that their subscribers are otherwise subject to. This is a different flavor of net neutrality. And the prior FCC said that AT&T’s sponsored data plan, which is that zero rating kind of plan, looked like it was not lawful under the existing open internet rules. They did that in a report issued right before the Pai FCC came in. And Pai has now pulled that report of the table, along with a report saying that investment in infrastructure by the government is a really good idea. So he’s sweeping aside recommendations that the Obama FCC made because he doesn’t see them in line with the interests of these carriers.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I’m a little confused because you said it’s illegal for cities to offer only one internet service. And I hear what people are saying is if really we hadn’t done away with monopolies, then net neutrality would actually be able to work a little bit, by competition. Why are cities allowed to do this then if it’s illegal?

SUSAN CRAWFORD: Cities– well, there are a few issues there. What’s happened is that where it’s possible to consolidate, competition is impossible. So these carriers have divided up the country among themselves. And that’s why we’re you are, you might only be able to get Time Warner or now, Spectrum, and I might only be able to get Comcast. So there might be a number of providers in the nation, but where you sit, you’ll likely have just one.

Cities are able to offer in most states of the union things like dark fiber passive infrastructure that anybody could use to provide essentially a public option to those carriers’ services for internet access. Pai is interested in just helping the existing carriers do whatever they want. And that’s what we’re going to be seeing out of this FCC.

JOHN BRODKIN: If I could just add things here. It’s illegal for a city to give a cable company an exclusive contract and say no one else can come in. But that doesn’t mean that there have to be multiple companies. Ultimately, it’s the decision of private providers as to whether it’s worth going into a city or town. And what happens is you end up with de facto monopolies, not legal monopolies because when Comcast controls the customers in a city or town, it’s just not financially feasible for another provider to come in.

IRA FLATOW: OK, Susan Crawford, law professor at Harvard, and John Brodkin, senior It reporter at Ars Technica, thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.