Jane Goodall And Her Life In The Wild

24:46 minutes

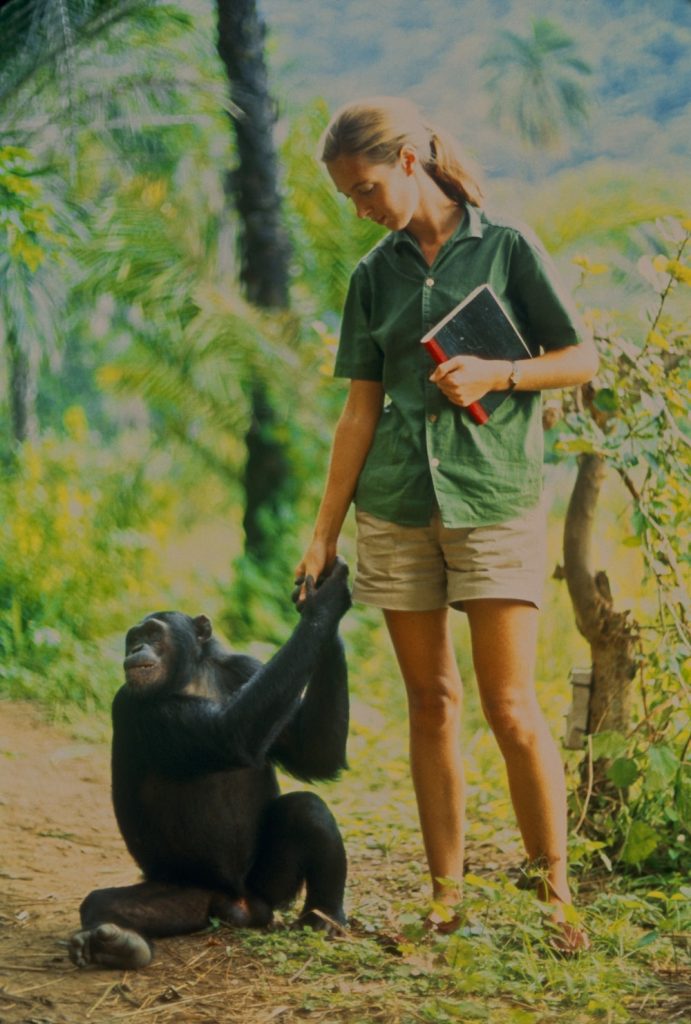

Over half a century ago, Dr. Jane Goodall journeyed into the Gombe Stream Research Center in Tanzania for the first time. It was in the unruly Tanzanian jungles that she would embark on the research that would launch her scientific career. The new documentary JANE follows Goodall into the field and recounts her work studying primates.

“All the time, I was getting closer to animals and nature and, as a result, closer to myself and more in tune with the spiritual power I felt all around,” she says in the film.

[How is a spider like a disco ball?]

Goodall entered Gombe as an amateur scientist, but the observations she emerged with would change our thinking about chimps, primates, and even humans. Goodall reflects on her years of experience in the field and the scientific efforts she is involved with today.

View the trailer for JANE, released in select theaters in October, and archival photos from her life.

See more of Jane Goodall on Science Friday.

Jane Goodall, DBE, is a founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and is a UN Messenger of Peace.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Over 50 years ago, Dr. Jane Goodall journeyed into the Gombe for the first time. She entered as an amateur, but when she emerged, her observations from that time would change our thinking about chimps, primates, and even humans. A new documentary called Jane comes out October 20, and it gives a previously unseen personal perspective of her time in Gombe.

Since that time, she’s worked to preserve the habitats of chimpanzees and involve communities to balance their own habitats. Dr. Jane Goodall, welcome back to “Science Friday.”

JANE GOODALL: Thank you very much.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And if you’ve got a question for Dr. Goodall about her work, give us a call. Our number is 844-724-8255. You can always Tweet us @SciFri.

You have said that this film, Jane, brings you back to Gombe more than any other movie. Tell us about that. What is it about these pictures that take you back to that time?

JANE GOODALL: You know, I’ve tried to work out what it is about it. I think because it shows more of me as a person and that very spontaneous relationship that developed between me and the chimpanzees. You know, I was able to groom David Greybeard, and of course, those are the kind of things that we absolutely don’t do anymore, because, well, we know chimps can catch our diseases and things like that.

But back then, it was a very naive, innocent sort of world. And the magic of being able to interact with creatures who’ve been running away from you for almost a year was something real special. And that comes out very strongly in this film.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You know, what else comes out very strongly is the solitude that you must have felt, especially early on, as you were attempting to communicate with or get close to the chimpanzees. Can you take us back to that time, that feeling of kind of being alone in the wild?

JANE GOODALL: Yes, well, that was my dream. I mean, that was the best part of it, you know. And there’s loneliness and alone-ness, and they’re two very different things. And I was never lonely, although when my mother left– you know, she came with me to start with, and that’s shown very clearly in this film, which– more clearly than the others. And of course, I missed her for a while when she’d gone. But being alone in the forest, for me, is one of the most magical aspects of those days.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What was it like seeing yourself as the subject of the film and not necessarily the chimpanzees, because this film does linger on you as the subject, not so much on the chimps that you were researching?

JANE GOODALL: Well, I’ve sort of got used to it a bit. I’ve written about that, you know, my books. My autobiography Reason to Hope is pretty honest about who I am. But it was seeing me back then, you know, those images, through Hugo’s lens, and all that amazing photography. He really was a genius with making the films that he did.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Take us back to the feeling of the first time that you really made contact with one of the chimps. What was that like for you?

JANE GOODALL: Well, it was absolutely extraordinary. I mean, it was when– the one chimp who began to lose his fear first was a male. I called him David Greybeard, because he had a beautiful white beard. I’m not quite sure why David Greybeard, but anyway, that came to be his name. And he came into my camp and pinched some bananas.

So then I asked the cook, Dominic, to put bananas out. I was still going into the hills every single day, into the forest. Mama had gone. And eventually, he began coming fairly regularly.

And so I stayed down, got to know him better. And the first time he actually approached and took a banana from my hand, it was like the stories you read about people approaching un-contacted human tribes. That’s how it felt.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And of course, then it somewhat quickly goes wrong, in that the chimps discover that they can get bananas pretty easily by just coming to your camp. And all of a sudden, you’re hiding behind screens as they ransack through the place. What did that feel like? Maybe your experiment gone a bit wrong?

JANE GOODALL: Well, it wasn’t an experiment, really, and it was just the odd banana until Hugo came. And then, you know, Geographic sent him. The Geographic needed footage out in the forest with chimps who aren’t really habituated. He wouldn’t have got much. It would mostly have been from a distance, and they’re black in a dark forest.

So he realized that, ha, the chimps coming into camp will be easier to film. And so he was the one who organized regular feeding. And it did go wrong, and they became very aggressive until we designed these boxes, which calmed them down and stopped the fighting that was going on. But you see, if we hadn’t done that, the Geographic wouldn’t have gone on funding Hugo to sit, getting very little, and the research would have ended.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Well, one of the most touching parts of the film is your relationship with a chimp named Flo and her baby. I guess I’m wondering what you learned about Flo as a mother and about motherhood through that experience.

JANE GOODALL: Well, I learned a lot. And over the years, I’ve learned there are good mothers and not-good mothers. There’s very few bad mothers, just one or two we’ve known. And Flo is just a perfect example of the very best kind of mother. She was affectionate, protective but not over-protective, and above all, supportive.

And of course, that’s what I attribute so much of my own success to, the way mum brought me up, my mother. She supported my dream of going to Africa when everybody else laughed at me. I was 10 years old at the time. And so finding out that chimpanzee offspring who have had a supportive mother have tended to do better, be better mothers, rise higher in the hierarchy if they’re males– and so it just stresses the importance of the first couple of years of life and the kind of upbringing that you have.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I should ask you about this, because later in our program, we’re going to be talking about a study that’s taking a close look at baby talk, how humans talk to babies and what we’re learning about it. Did you notice that– do chimps have a different way of talking to their babies than they talk to other chimps?

JANE GOODALL: No, I don’t think– well, I mean, no, not really.

JOHN DANKOSKY: No?

JANE GOODALL: But one of the interesting things with a chimp mother and child is there’s very little need for any sound communication between them, because the baby is always clinging to the mother. If the baby is in danger of slipping, the mother feels it pulling on the hair. And if the child’s in distress, the mother just cradles it a bit closer. So it’s, you know, when you start being separated from your babies that the need for vocal communication gets much more important.

JOHN DANKOSKY: In the film, you say that in your dreams, you would dream as a man that went on adventures. Why did you dream as a man, do you think?

JANE GOODALL: Well, because when I was young, you know, 80 years ago, men did things that girls weren’t supposed to be able to do. And so as I wanted to do things like going out in the forest and living with wild animals, I thought it would be much easier if I was a man. So I suppose that’s why I dreamt I was a man. I don’t know.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Do you think often of how your work in the field changed the way that women scientists think and dream about their futures?

JANE GOODALL: I didn’t think about it at the time, of course. And you know, when I began, I had absolutely no plan of being a scientist. I just wanted to be a naturalist. And it was Louis Leakey, my mentor, who told me I absolutely had to get a PhD to be properly recognized and to get funding.

JOHN DANKOSKY: But at the time, when you first went into Gombe, you were an amateur. You did not have training. How do you think that that helped you do the work that you and Hugo did together, that you were both new to this and that you didn’t have the scientific training of maybe others who would have taken that voyage?

JANE GOODALL: Yeah, well, first of all, there was nobody who could have trained me because nobody had done it before. That was the luck. I was sort of out there first. And Louis Leakey deliberately chose me because he said he wanted somebody whose mind was uncluttered by the, in his opinion, sometimes not good scientific thinking.

And you know, I completely agree with him. So when I got to Cambridge to do a PhD because he insisted, I was told I couldn’t talk about chimpanzees having personalities, minds capable of thinking, and certainly not emotions. You know, I was guilty of anthropomorphism.

But fortunately, though I was really intimidated by these clever, clever professors at Cambridge, I’d had this wonderful teacher when I was a child who taught me that in this respect, they were wrong. And that was my dog. You know, you can’t share your life in a meaningful way with a dog, a cat, a bird, a cow, I don’t care what, and not know of course we’re not the only beings with personalities, minds, and emotions.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You said earlier that as you look back on this film, you notice all the things that you wouldn’t have done now, ways in which we’ve learned how to interact with chimpanzees that obviously no one knew at the time. What are some ways in which as you look back at this film Jane that you see something that you’d do completely differently with all the knowledge that you have today?

JANE GOODALL: Well, the only thing that we do differently is to have more sophisticated ways of actually recording the data. You know, you can use electronic gadgets. When I began, it was a notebook and pen, or pencil in the wet season, and typing it up at night so that they were very long days. And then we graduated to filling a lot of the stuff in on check sheets and tape recorders.

But you know, the only thing really different today is that we no longer have the banana feeding. We no longer have any interaction with the chimpanzees. But otherwise, the study has really gone on very much the same.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I’m John Dankosky, and this is “Science Friday” from PRI, Public Radio International. And we’re talking today with Dr. Jane Goodall. If you want to join our conversation, 844-724-8255. You can also Tweet us @SciFri.

One of the, of course, first things that you learned that struck the psyche of the world was how chimps can use tools like humans. And of course, they have these very intricate social structures that you observed, all of which kind of made people feel positive about the– not only the relationship between chimpanzee and human but also about humans ourselves. But you also observed, and I think it’s well-illustrated in this film, the flip side of that, with different groups of chimps fighting, almost going to war, and killing one another. Do you think that by observing chimpanzees, you learn something about humans and their tendency to war with one another?

JANE GOODALL: Yeah, I do, actually. And I remember vividly in the early ’70s that this consideration of whether aggression is innate in us or learned. And the two sides were fighting bitterly, one group of people saying, of course aggression is innate. It’s in our genes. And the other saying, no, no, it’s only learned. Children are born with a blank slate, and it’s what we put into that slate that makes them aggressive.

And Louis Leakey sent me because he believed there was an ape-like, human-like creature about six million years ago from which humans and chimpanzees and the other apes evolved. And his theory was, if Jane finds behavior that’s similar in chimps today and humans today, it’s possibly come with us through our long evolutionary journeys. And it would help him to better imagine how the early humans whose skeletons, fossilized remains, he was searching for might have behaved. So I was always very firmly of the opinion that we do have aggressive tendencies. And of course, they can be enhanced or– to even teach a child, you can encourage the child to suppress those aggressive tendencies.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Do you find us becoming a more aggressive culture?

JANE GOODALL: Well, right now, I think the world is not in a very happy state, is it? I mean, when we think of the terrorism, the terrorist attacks, the bombs, the guns, we think of the different countries where there is actual conflict going on. And we think of gangs and gang warfare and bullying in schools and all these other bad aspects of humanity. It’s very disturbing, I think.

JOHN DANKOSKY: When we come back from a break, we’re going to talk more about the work that you’re doing today, with not only humans but also around the world to teach conservation. If you’ve got questions for Dr. Jane Goodall, 844-724-8255. That’s 844-SCI-TALK. Of course, you can also Tweet us @SciFri.

This is “Science Friday.” I’m John Dankosky. Ira Flatow is away. We’re talking this hour with Dr. Jane Goodall.

There’s a beautiful new documentary coming out October 20 called Jane. It follows her time in the Gombe researching chimpanzees. And if you want to ask her questions, 844-724-8255. Let’s go to Christine, who’s calling from Baltimore. Hello, Christine, you’re on “Science Friday.”

CHRISTINE: Hi, thank you for taking my call.

JOHN DANKOSKY: What’s on your mind?

CHRISTINE: Hello, doctor. Hi, I wanted to say hello to Dr. Goodall and commend her on her amazing lifetime body of work. Dr. Goodall, you’re one of my childhood heroes. And I’m an early childhood educator in Baltimore, Maryland, and my question is– I wanted to ask, what are the most important things that educators can do to really get children involved in the ideas of animal science and animal conservation?

JANE GOODALL: Well, I think, you know, one very, very important thing is to try and find out what really interests the child. And if the child totally is interested in mechanics and things like that, then I think the important thing is to give them a chance to experience nature. And I know some children, you know, don’t have the luxury of going out into national parks and things, but there’s always some earth and some growing things.

And you know, we used to put a seed behind blotting paper in a damp jar and watch the little roots come out between the damp paper and the glass and see that little shoot come, and watch snails and– how do they walk without legs? And gosh, pop them on the other side of a window and watch that rippling movement. I mean, these things fascinate even children who are not particularly interested in the outdoors.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Christine, thank you so much for your phone call.

CHRISTINE: Thank you very much.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I want to get to one more quick phone call. Mira is calling from Cambridge. Hi there, Mira.

MIRA: Hi, Dr. Goodall. I’m calling to salute you for founding the Roots & Shoots network that provides a platform for young people, for youth, to get involved in environmental action in their communities and also to help animals and people. I had the honor of meeting you in 2008 in China, when I worked for Shanghai Roots & Shoots.

And after I left Shanghai, I took with me the program that I worked on called the Eco Audit Program, in which the youth help businesses reduce their carbon footprint and become more environmentally conscious in their daily work practices. And I’ve since then started it in Delhi, here in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and it’s soon going to be started in Mumbai. And I want to acknowledge you, because through Roots & Shoots, you are the inspiring, you know, force for this, and it’s been very transformative for not only the young people but also the businesses they interact with on this program. So thank you. And God bless.

JANE GOODALL: Oh, thank you. Thank you for that.

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s a lovely thought, and I think a lot of people who are calling wanted to maybe have you talk more about the Roots & Shoots program that does help so many youth, not just obviously here in America but around the world. Tell us more about what it’s doing right now.

JANE GOODALL: Well, Roots & Shoots was begun because when I learned that chimpanzees were decreasing in numbers and forests were vanishing, and I realized that I had to leave the Gombe that I loved and try and help the chimps. And in learning more about the chimps by going to different African countries, I learned more about the problems faced by the people, living in poverty without good health and education. And so that began our program to improve the lives of the people, otherwise you can’t help to conserve nature and animals. And that takes a lot of hard work, and it costs money.

So I realized then, there’s not much point in all of this hard work if we’re not raising new generations to be better stewards than we’ve been. And so Roots & Shoots began with 12 high school students in Tanzania in 1991 who were concerned about the way animals were treated, poaching in the national parks, destruction of coral reefs with illegal dynamite fishing, street children, all sorts of different things, these 12 students. And we had a big meeting with their friends, and Roots & Shoots turned into this program where the main message is each individual matters. Each one of us makes a difference every single day, and we can choose what sort of difference to make.

Each group chooses themselves– we don’t tell them what to do– three projects to make the world better, to help people, to help animals, to help the environment. And it’s now in 100 countries with members from preschool through university, about 100,000 active groups. And all the people who’ve been through that program and who now come and tell me, well, you know, we learned to care about the environment or animals or social issues when we were in Roots & Shoots.

And I’m, you know, the last question came from somebody who learned about Roots & Shoots in China, and it’s all over China now, and there they’re telling me, you know, well, yes, of course we care about the environment. We were in Roots & Shoots in primary school.

JOHN DANKOSKY: You talked the last time you were on “Science Friday” a bit with Ira about wanting to instill hope in young people. And you know, as we were talking about earlier, with the state of the world in some ways, there’s a lot of reasons to not be hopeful. When you go around the world talking with young people, young burgeoning scientists today, do you sense that there’s hope for the future, not just for animals but for people, too?

JANE GOODALL: Well, I think that certainly– you know, my greatest reason to hope, and this is what I share, is that the young people, once they know what the problems are and we empower them to take action to become involved in something they care about, then they’re filled with hope, because they know that what they’re doing is making a difference. And then they know that through our Roots & Shoots network and other similar groups, young people all around the world care just like they do. And you know, I believe we have a window of time to put things right, so that, along with the human brain, our amazing inventiveness, along with how incredibly resilient nature is if we give her a chance– even places totally destroyed can once again support life, and animals on the brink of extinction can be given another chance.

And then there’s the indomitable human spirit. You know, the people who recover from terrible illnesses, they cope with disabilities, they tackle projects, problems that seem insoluble and don’t give up. And it’s really lucky that we have this indomitable spirit.

You know, I’m looking out of my window here in San Francisco. And it’s thick with smoke, so when I was coughing earlier, it’s these terrible wildfires. And if young people give up from things like wildfires and floods and hurricanes and climate change– which actually is real. I’ve seen it for myself, and I know that we’re a great contributor to it. So it’s desperately important now more than ever that young people don’t lose hope, because if you don’t have hope, you just– well, why bother to do anything?

JOHN DANKOSKY: Now I do have a question that because you’ve been on science several times over the years, you probably know I’ll ask about. Ira wants to make sure we ask you about yetis or Sasquatch or Bigfoot. Have we picked up any more clues, any closer to solving the yeti mystery?

JANE GOODALL: We haven’t, and you know, it’s so peculiar. I want to believe there is a creature, whether it’s a yeti, whether it’s Sasquatch, whether it’s the Yowie in Australia or the wild man in China. So many people, especially indigenous people– and my best story, which I’ll tell very quickly– I went to a place in Ecuador, flew over miles and miles of untouched rain forest, landed with a little community of about 30 people. And in the area, there were six, seven such little communities. And the only communication between them were these hunters who went from village to village with news, like the old minstrels.

And so I asked a translator, next time you see one of these hunters, please ask them if they’ve seen a monkey without a tail. That’s all I said. And so this guy had no idea where I was– why I was asking. And about six months later, I received a reply that four of the hunters had– and they’re all separate from each other. They’d all seen monkeys without tails, and they walked upright, and they were about six foot tall.

JOHN DANKOSKY: We’re going to–

JANE GOODALL: That’s pretty amazing, isn’t it?

JOHN DANKOSKY: It’s a pretty amazing, funny– I’ll tell you, we’re going to keep looking with you, Jane Goodall, into the future. And we’re so glad that you were able to join us.

Dr. Jane Goodall, primatologist and founder of the Jane Goodall Institute. Thank you for joining us today. I really appreciate it.

JANE GOODALL: Well, thank you for inviting me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Jane is the new documentary coming out October 20. It follows her time in the Gombe. You can see photos on our website at sciencefriday.com/jane.

Copyright © 2017 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.