Order And Disorder In The Human Brain

22:47 minutes

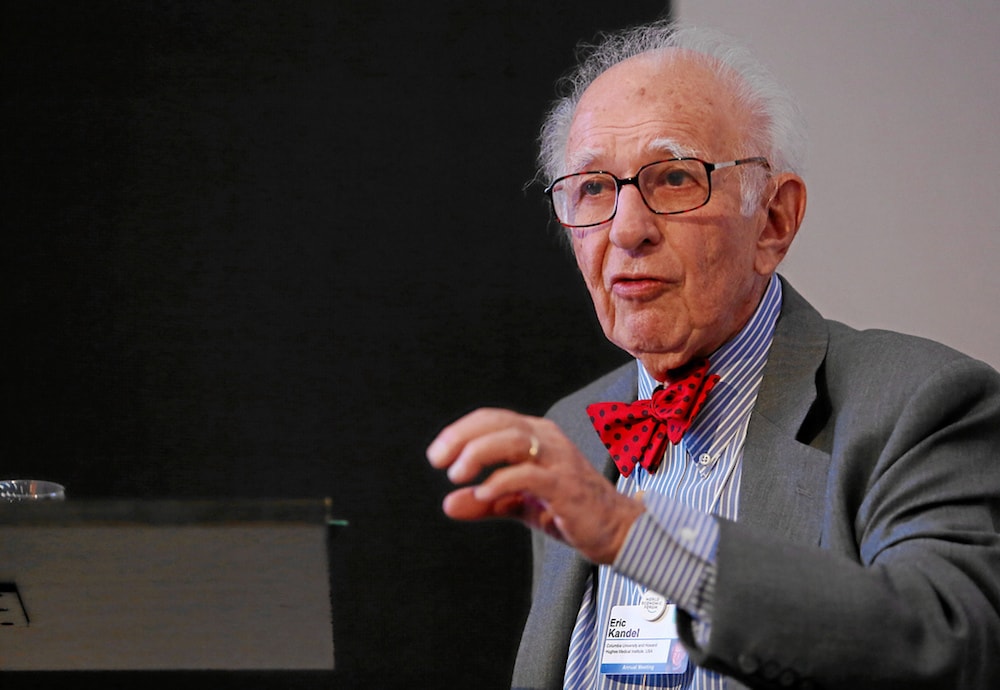

The human brain contains an estimated 100 billion neurons. When those cells malfunction, the disrupted process can lead to schizophrenia, PTSD, and other disorders. In his book The Disordered Mind, Nobel Prize-winning neuropsychiatrist Eric Kandel looks at where the processes fault to give insight into how the brain works.

[Half of the planet’s oxygen comes from tiny plants under the ocean’s surface.]

For example, PTSD patients can reveal how conscious and unconscious emotion are connected to decision-making in the brain. And how Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease, which have different symptoms but similar molecular mechanisms, can tell us how the brain processes movement. According to Kandel, the understanding of these disorders offers a chance “to see how our individual experiences and behavior are rooted in the interaction of genes and environment that shapes our brains.” He joins Ira to discuss.

On the possibility of treating PTSD with virtual reality.

If you have post-traumatic stress disorder, you’ve observed a very frightening experience that had consequences. For example, a machine gun goes off near you and two of your buddies get hit and are seriously wounded. Next time you just hear sounds going off and you are frightened terribly by it. So, one way to treat something like this is to put a person in an absolutely safe environment where they know nothing is happening and play those sounds so they sort of become habituated with it. They realize that not every time they hear a terrible sound necessarily means an actual catastrophe for another person.

On the difference between Alzheimer’s disease and age-related memory loss.

The pathology of Alzheimer’s disease is very different from age-related memory loss, and age-related memory loss actually often begins before Alzheimers disease, which begins in the early 70s. And age-related memory loss can be reversed.

In experimental animals, my colleagues and I may have shown that a hormone released by bones called osteocalcin reverses it, and you can show in experimental animals that age-related memory loss can be reversed by just getting the animals to walk a lot… when you walk, you release [osteocalcin], and the more you strengthen the bones, the more capable you are of doing that. This is not a proven deal, but I think a very attractive avenue to explore.

On why Alzheimer’s treatment has been ineffective.

By the time somebody presents with the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, they’ve already lost a lot of nerve cells. If you initiate treatment you can’t get those cells back. All you can do is save future damage. So, we somehow need an earlier way to make the diagnosis, either routinely—everybody over 40 gets annual brain imaging—or if there’s the slightest clue. But even by that time you’ve lost a lot of nerve cells. One thing one has to realize that unlike liver cells and other cells, brain cells don’t regenerate. If you lose certain brain cells you’ve lost them, kid. That’s it.

On the possibility of the brain repairing itself.

It’s possible. If the damage is slight and the brain has rested or there is not that much activity in that area, then repair can occur. It’s not that common but it can occur… But the brain does not repair itself by growing new cells. It repairs itself by [repurposing other cells] it already has.

On viewing mood disorders as personal weaknesses rather than diseases.

It’s ridiculous. And this is why people with psychiatry have really been dismissed by society so often. That’s no longer the case now, by and large, but it was thought to be bad behavior or a bad upbringing or something like that instead of realizing this is a disease like Parkinson’s disease or any other neurological disease. I think [the resistance to it] is a poor understanding of what is a disease and what is not. A lot of diseases manifest themselves as awkward behavior instead of disorders in walking or speaking or something like that, which is obviously not something which is put on or learned.

On the similarities between these kinds of disorders.

What is the brain concerned with? It’s concerned with who we are, what makes us who we are. What makes us loving human beings, what makes us aggressive human beings. And as we understand more the biological underpinnings of it, we will understand more the detailed mechanisms of it, and really get a biological humanism.

Eric Kandel is the winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and co-director of the Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Behavior Institute at Columbia University in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Dr. Kandel certainly needs no introduction to you Science Friday listeners. The 2000 Nobel Prize winner in physiology or medicine and co-director of the Mind Behavior Institute at Columbia University has spent his entire career working to understand the brain and what makes us who we are. And he has a new book, The Disordered Mind– What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves. And you can read an excerpt of this incredibly great book– I think it’s his best work– at our website at sciencefriday.com/disordered. And Dr. Kandel, Eric, is here with us. Welcome back. It’s always a pleasure to have you.

ERIC KANDEL: Thank you. It’s a pleasure for me to be here, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You know, in this book, you examine the brain by watching what happens when things go wrong in the brain, disease and illness. And it was interesting in your notes, you say this is an observation that you first made way back in your medical school days and thought about, gee, this is what I want to know about.

ERIC KANDEL: Well, in some ways, it’s a tradition within neurology that we learn a lot about disorders of brain teaches us about how normal function occurs. So from that point of view, I was influenced very much about the tradition within neurology. It has not been as characteristic of psychiatry, the field I came from. But psychiatry and neurology are merging, really, because– psychiatry really emerged as a discipline originally because people thought that the mind was different from the brain. Now we realize that all mental processes are brain processes and that neurology and psychiatry have many features in common.

IRA FLATOW: In your book, you say that as we understand these disorders better, more and more similarities will emerge.

ERIC KANDEL: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: And that’s the key?

ERIC KANDEL: Absolutely. That’s the key.

IRA FLATOW: The convergence will contribute to a new scientific humanism. What do you mean by that?

ERIC KANDEL: Well, what is the brain concerned with? It’s concerned with who we are, what makes us who we are, what makes us as loving human beings, what makes us as aggressive human beings. As we understand more of the biological underpinnings of it, we’ll understand more of the detailed mechanisms of it. And we’ll really get a biological humanism. We’ll understand humanistic issues in terms of biological mechanisms.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask you to help translate some of the news that’s been happening this week in brain science. An international team has identified a kind of brain cell that exists in people, but not in mice. And they– in Nature Neuroscience, it was published. They dubbed it the rosehip neuron. Do you know anything about that?

ERIC KANDEL: I saw that. And I think it’s a very nice finding. I felt it was a little bit overhyped, if I may say so. Mice are not people. We do a lot of experiments on mice. And we can do lots of experiments that are relevant to people. But clearly, if you look at the brain of a mouse and you look at the brain of a person, it’s very different. So to have a nerve cell that’s present in humans and not in mice doesn’t blow me away. Turns out that apes also have this neuron. So that tells you at least, it’s a feature of the primate brain. What its importance is is hard to know. It may be quite important, but it may not be terribly significant. I think it’s too early to know.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s get into some of the details in your book, because you cover just about every brain disorder or illness that we can think of.

ERIC KANDEL: Well, I mean, those are interesting problems in the psychiatric ward– schizophrenia, depression. We have relatively little insight into the underlying biology. We’re beginning to make some progress, but we don’t have a deep insight.

IRA FLATOW: You write– in the section about autism, you write that despite advances in science and medicine, many people continue to view mood disorders as personal weakness, bad behavior, rather than a set of illness.

ERIC KANDEL: It’s ridiculous. And this is why people with psychiatry have really been dismissed by society so often. That’s no longer the case now, by and large. It was thought to be bad behavior, bad upbringing, or something like that, instead of realizing, this is a disease like Parkinson’s disease or any other neurological disease.

IRA FLATOW: And what was the resistance to that? Was it hubris? I mean–

ERIC KANDEL: I think a poor understanding of what is a disease and what is not.

IRA FLATOW: And a lot of diseases are based in your brain? That’s chemistry.

ERIC KANDEL: Of course. That’s true. But a lot of diseases manifest themselves as awkward behavior instead of just disorders of walking or disorders of speaking or something like that, which is obviously not something which is put on or learned.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking about that, you gave us a tour of the biology behind all sorts of disorders. And from what– as I say, we’re on autism now, you talk about– there used to be this refrigerator mom hypothesis. It was because the mom, the parent–

ERIC KANDEL: Crazy, crazy. It’s very easy when something develops early in childhood to blame it on the parents. We now realize that although the parents obviously contribute importantly to the development of their children, there are many things that are independent of parental behavior.

IRA FLATOW: Are you saying in the book that we are actually finding genes that are related to autism?

ERIC KANDEL: Yes, yes, yes.

IRA FLATOW: Is it a single gene? Or is it multiple genes?

ERIC KANDEL: Several genes.

IRA FLATOW: Several genes.

ERIC KANDEL: Yes, yes. That’s going to be really a major advance in the next 20 or 30 years– genetics is becoming so powerful– to understand what are the genes that are altered and to see whether we can develop pharmaceutical approaches that will be able to help out. And I think we’ll be able to do that better if we understand the genetic basis of it.

IRA FLATOW: Our number, 844-724-8255 if you’d like to talk with Dr. Kandel. Or you can tweet us at SciFri. Speaking of genes, something that was fascinating to me when reading all about stuff that you can do, the idea that we can repair cells at the synapse versus any other way. I hadn’t thought about that before. Would you say that is a frontier?

ERIC KANDEL: That is a frontier, to see whether one can inject into the cell body molecules that will allow you to repair the synapse at the periphery. It’s a major effort going on right now.

IRA FLATOW: Synapses is where the–

ERIC KANDEL: Neurons contact their targets, either another cell or a muscle.

IRA FLATOW: And if there’s a–

ERIC KANDEL: Point of communication.

IRA FLATOW: It communicates by sending out chemicals across the boundary?

ERIC KANDEL: Exactly. There are actually two kinds of synapses. There are electrical and there are chemical. There are some synapses in which the current actually flows from one cell to another. Not that common in the mammalian brain, but there are some synapses like this. The more common synapses is that one neuron, called the presynaptic neuron, releases a chemical substance, a transmitter, that acts on the target cell.

IRA FLATOW: It’s quite fascinating.

ERIC KANDEL: It’s quite fascinating.

IRA FLATOW: It is fascinating. Let’s talk about stress.

ERIC KANDEL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: I mean, it’s killing us all. Right?

ERIC KANDEL: So a lot of us are under stress.

IRA FLATOW: And you actually show the molecular pathways and things that are going on. You talk about cortisol destroying synaptic connections. What is cortisol? What do you mean by destroying–

ERIC KANDEL: It’s released by the adrenal gland, which is capable, in higher amounts, or if it’s taken as a drug, or ingested in some other way, of interfering with connections between nerve cells and synapses. As you can imagine, the synapses– which are very delicate, refined, and interesting molecular machinery, whereby one cell communicates to another– has many components to it, so it’s very susceptible to interference and disruption.

IRA FLATOW: Is it possible for the brain to repair?

ERIC KANDEL: Yes, absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: We never thought that was possible.

ERIC KANDEL: No, but it’s possible. If the damage is slight and the brain is rested, or there is not that much activity in that area, repair can occur. It’s not that common, but it can occur.

IRA FLATOW: How many disorders, you say– you do say that for many disorders, the early treatment is key. Can you stop progression of something like PTSD or schizophrenia as it progresses, if you–

ERIC KANDEL: Schizophrenia is not terribly progressive. It may progress to some degree. But I think with most diseases, if you interfere with them early, in the early stages, you’re more likely to be able to limit its detrimental action.

IRA FLATOW: You talk about this early intervention in mental disorder and the lack of it. And you say that scientists have successfully identified high risk lifestyles for heart attacks and developed interventions for them, why not the same for mental diseases?

ERIC KANDEL: Well, they’re beginning to do this, right? I mean, certainly, you see that people have a tendency to sadness or depression– interfering early, pharmacologically and psycho therapeutically, will be very helpful. Once the disease really becomes ingrained in a person’s lifestyle, it becomes much more difficult to counteract it.

IRA FLATOW: 844-724-8455. Let’s see if we can get a call in before we go to the break. Jim in Pacific, California. Hi, Jim.

JIM: Hi, how are you doing?

IRA FLATOW: Hi there, go ahead.

JIM: I was a big fan of all Oliver Sacks and really loved his books– Hallucinations– and he seemed to have a point that as a species, we have really failed and neglected to mentor human attributes like synesthesia or these kinds of what you could call disorders. And as an occupational therapist, I treated them for years. But how much we’re missing about the potential for human growth and development with a lot of things that we classify as, in the old days, demon-induced and all this other stuff.

ERIC KANDEL: Well, you know, it’s a very fine line. It depends to what degree this trait interferes with the functioning of an individual. If somebody has some neurological or psychiatric peculiarity, but it does not interfere with their life– in some cases, may make their life richer– then by all means, one does not want to interfere with it.

IRA FLATOW: We’re going to take a break and go to break. When we come back, we’ll talk about some of the interesting treatments and modalities. For example, you talk about in your book, treating PTSD with virtual reality. I want to take a break, and that sounds fascinating. Talking with Eric Kandel, author of The Disordered Mind, What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves. Our number, 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us at SciFri. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday, talking with 2000 Nobel Prize winner, Eric Kandel, author of a really, really good new book, The Disordered Mind, What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves. And if you’ve listened to me interviewing Eric over the years, I always say this is your best book.

ERIC KANDEL: The best is yet to come, you mean. I’m so young. Seriously? Are you 91 now? Not yet. 89.

IRA FLATOW: 89?

ERIC KANDEL: November 7th.

IRA FLATOW: [INAUDIBLE], as they say in your–

ERIC KANDEL: November 7th.

IRA FLATOW: November 7th. Congratulations. But this really is. I mean, the way you were able to, in layman’s language, describe all of these things. And a beautiful, color diagram.

ERIC KANDEL: I had a very fortunate experience. Two fortunate experiences. I was in high school at Erasmus in Brooklyn– wonderful high school– and [? Mr. Campana, ?] my history teacher, asked me, where are you applying to college? And I said, I’m applying to Brooklyn College. It’s a very good school. My brother’s going there. He said, ever thought of Harvard? I said, no. He said, why don’t you apply to Harvard? So I went home, discussed it with my parents, and we were refugees, we had very little money. And my father said, look, we’ve already paid $10 to apply to Brooklyn College, an excellent school. So [? Mr. Campana ?] gave me the $10, I got accepted at Harvard with a scholarship. And at Harvard, I majored in history and literature. And I wrote all the time. I wrote essays all the time. And I really began to enjoy writing. And many of the things that I did later on–

My colleagues, for example, scientists very much at my level very rarely write for the general public. I mean, they write terrific papers, they do excellent science. But they’re not as comfortable writing as I became in college.

IRA FLATOW: You had no training, formal training, in writing at all? You’re a natural at it.

ERIC KANDEL: Well, I had a tutor who looked at the essay. Didn’t look at it just in terms of style, but looked at the content but commented on the style. So that certainly helped me. But I just did a lot of writing.

IRA FLATOW: Well, it’s paid off.

ERIC KANDEL: How do I know what I think unless I read what I write?

IRA FLATOW: Oh, let me write that down.

ERIC KANDEL: Well, it’s true in a way.

IRA FLATOW: It’s true. It is true.

ERIC KANDEL: Clarify your thinking. But often, when I sit down to write something, my thought process about it are no way as clear as ultimately emerges from the written text, because the written text is not one draft, but 10 drafts.

IRA FLATOW: Right. Right. It’s true. It’s true. If you can explain it to someone else, you understand it yourself.

ERIC KANDEL: Absolutely. Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s get this. So much in this book. Let me talk about what I mentioned before the break. And that is, treating PTSD with virtual reality. How is that working?

ERIC KANDEL: Well, so, if you have post-traumatic stress disorder, if you observed a very frightening experience that had consequences– So you know, a machine gun goes off near you and two of your buddies get hit and are seriously wounded. Next time, you just hear the sounds going off and you’re frightened terribly by it. So one way to treat something like this is to put a person in an absolutely safe environment where they know nothing is happening and play those sounds. So they sort of become habituated with it. They become accustomed to it. They realize that not every time they hear a terrible sound does that necessarily mean an actual catastrophe for another person.

IRA FLATOW: So people are doing this?

ERIC KANDEL: They’re doing this.

IRA FLATOW: That’s quite interesting. Of course, we couldn’t talk about brain without talking about memory, your topic.

ERIC KANDEL: I like memory.

IRA FLATOW: It’s a topic you should go into.

ERIC KANDEL: One of my favorite topics.

IRA FLATOW: So what’s new with memory?

ERIC KANDEL: In the last few years?

IRA FLATOW: What is the new thinking on memory? I know you make major contributions to this and you have a Nobel Prize. I mean, OK, let’s talk about age-related memory versus Alzheimer’s or other kinds. They are separate, and you make that point in your book.

ERIC KANDEL: Yes. I actually have done a lot of thinking about that and made a little conceptual progress. I think that as people age, they’re susceptible to two kinds of memory disorders– Alzheimer’s disease and age-related memory loss. And they’re really quite different. The pathology of Alzheimer’s disease is very different from age-related memory loss. And age-related memory loss actually often begins before Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s disease begins in the early 70s. Age-related memory loss can be reversed.

IRA FLATOW: It can?

ERIC KANDEL: Yes. And in experimental animals, one can show– and my colleagues and I at Columbia have shown this– that a hormone released by bone, called osteocalcin, reverses it. And you can show in experimental animals that age-related memory loss can be reversed by just getting the animals to walk a lot. So I’ve given up my routine of swimming– I’ve reduced it– and I’m substituting walking for swimming. And I’ll report back next time we talk.

IRA FLATOW: You see these pictures of Ruth Bader Ginsburg doing her exercises, right? And so, it’s by strengthening your bones?

ERIC KANDEL: Your bones release a hormone called osteocalcin. And when you walk, you release that hormone. And the more you strengthen the bones, the more capable you are of doing that. This is not a proven deal. This is, you know, I think, a very attractive avenue to explore.

IRA FLATOW: A few weeks ago, in your book, you talk about the famous miner and the brain, and the rod that went through his brain and all that. But a few weeks ago, there was a story of a six-year-old boy who lost his entire occipital lobe, and much of his temporal lobe were removed. And the doctors report, he’s the same old guy. How do you explain all that? A sixth of his brain supposedly was gone.

ERIC KANDEL: If this were to happen to the kid when he was 18 years old, that would not happen. The immature brain is capable of regenerative capabilities. But that’s true for many parts of the body. Before puberty, we have regenerative capabilities in many organs of the body that we don’t have after puberty.

IRA FLATOW: Going back to Alzheimer’s, do we know what causes it? I mean, do we– we talk about the tangles and whatever in the brain. There was a time– maybe that is gone– we didn’t know if those tangles were the cause or the effect. Do we know now?

ERIC KANDEL: We have reason to believe that they’re a contributing factor to the cause. The reason we have not been effective in treating Alzheimer’s disease is that by the time somebody presents with symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, they’ve already lost a lot of nerve cells. So if you initiate treatment, you can’t get those cells back. All you can do is save future damage. But you already have a serious disease. So we somehow need an earlier way to make the diagnosis. Either routinely, everybody over 40 gets an annual brain imaging. Or, if there’s the slightest clue– but even by that time, the slightest clue means you’ve lost a lot of nerve cells. One thing one has to realize, that unlike liver cells and other cells, brain cells don’t regenerate. So if you lose certain brain cells, you’ve lost them, kid. That’s it.

IRA FLATOW: So then how does the brain repair itself, then?

ERIC KANDEL: The brain does not repair itself by growing new cells. It repairs itself by hooking up what it has. You can’t grow new cells.

IRA FLATOW: So it repurposes other cells?

ERIC KANDEL: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: That’s fascinating. Let’s see if we can get a few phone calls. Justin in Newbern, North Carolina. Hi, there. Welcome.

JUSTIN: I’m just wondering what your thoughts are on artificial help, with, you know, cannabinoids, THC, CBD, things like that, in order to combat PTSD, Alzheimer’s, things of that nature. What you might have to say about something like that?

IRA FLATOW: OK.

ERIC KANDEL: I think there’s a great future in that, because unlike some organs of the body, the nerve cells don’t regenerate, as we mentioned. So if you really lose a significant number of cells, you need something to compensate for that. And if, you know, a device of some sort can be plugged in and connected to the brain in some way and substitute for the missing function– and people are beginning to explore that– that would be wonderful. I mean, it’s nothing like having your brain do it, but it compensates for many of the deficiencies that you would have. And you would have a meaningful life in your older years.

IRA FLATOW: Have you see Michael Pollan’s new book about the LSD and treatments like that that they’re experimenting with? It’s not your field, so–

ERIC KANDEL: No, no, no. I just haven’t read it yet.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. It’s quite interesting. Now, just a few more minutes left. A half hour goes by pretty fast. Where are the wrong places that people are investigating in this? And where are the right places in brain science and mental illness? Where is the right– where’s the hottest area that people are–

ERIC KANDEL: Well, certainly, the area we know least about– that’s where you would hit a home run if you made a major breakthrough– is consciousness. Now, where does consciousness reside? I started stuff down there. A few people are beginning to work with that. But it’s–

IRA FLATOW: Is it possible to understand– can we understand our own mind by being inside our own mind?

ERIC KANDEL: Why not? I study my mind by studying your mind, right? I assume that consciousness in your brain is going to use mechanisms very, very similar, if not identical, to those in my brain. They may be more extensive in your brain, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. But the mechanisms are almost certainly identical.

IRA FLATOW: Sounds very much what Einstein said when he was asked about, can we comprehend the universe? And he said, the most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.

ERIC KANDEL: It is comprehensible.

IRA FLATOW: Eric, we’ve run out of time.

ERIC KANDEL: We just started.

IRA FLATOW: We’ll have you back, OK? Any time you want to drop in.

ERIC KANDEL: Very nice to have me.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, no. It’s always my pleasure. Anytime. Eric Kandel, winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, co-director of the Zuckerman Mind Behavior Institute at Columbia. And his new book is terrific– The Disordered Mind– What Unusual Brains Tell Us About Ourselves. An excerpt on our website at sciencefriday.com/disordered.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.