Huh? The Valuable Role Of Interjections

8:17 minutes

Host Ira Flatow is joined by reporter Bob Holmes to talk about his coverage of the role of interjections in conversation. This story was originally published in Knowable Magazine.

Listen carefully to a spoken conversation and you’ll notice that the speakers use a lot of little quasi-words—mm-hmm, um, huh? and the like—that don’t convey any information about the topic of the conversation itself. For many decades, linguists regarded such utterances as largely irrelevant noise, the flotsam and jetsam that accumulate on the margins of language when speakers aren’t as articulate as they’d like to be.

But these little words may be much more important than that. A few linguists now think that far from being detritus, they may be crucial traffic signals to regulate the flow of conversation as well as tools to negotiate mutual understanding. That puts them at the heart of language itself—and they may be the hardest part of language for artificial intelligence to master.

“Here is this phenomenon that lives right under our nose, that we barely noticed,” says Mark Dingemanse, a linguist at Radboud University in the Netherlands, “that turns out to upend our ideas of what makes complex language even possible in the first place.”

For most of the history of linguistics, scholars have tended to focus on written language, in large part because that’s what they had records of. But once recordings of conversation became available, they could begin to analyze spoken language the same way as writing.

When they did, they observed that interjections—that is, short utterances of just a word or two that are not part of a larger sentence—were ubiquitous in everyday speech. “One in every seven utterances are one of these things,” says Dingemanse, who explores the use of interjections in the 2024 Annual Review of Linguistics. “You’re going to find one of those little guys flying by every 12 seconds. Apparently, we need them.”

Many of these interjections serve to regulate the flow of conversation. “Think of it as a tool kit for conducting interactions,” says Dingemanse. “If you want to have streamlined conversations, these are the tools you need.” An um or uh from the speaker, for example, signals that they’re about to pause, but aren’t finished speaking. A quick huh? or what? from the listener, on the other hand, can signal a failure of communication that the speaker needs to repair.

That need seems to be universal: In a survey of 31 languages around the world, Dingemanse and his colleagues found that all of them used a short, neutral syllable similar to huh? as a repair signal, probably because it’s quick to produce. “In that moment of difficulty, you’re going to need the simplest possible question word, and that’s what huh? is,” says Dingemanse. “We think all societies will stumble on this, for the same reason.”

Other interjections serve as what some linguists call “continuers,” such as mm-hmm—signals from the listener that they’re paying attention and the speaker should keep going. Once again, the form of the word is well suited to its function: Because mm-hmm is made with a closed mouth, it’s clear that the signaler does not intend to speak.

Sign languages often handle continuers differently, but then again, two people signing at the same time can be less disruptive than two people speaking, says Carl Börstell, a linguist at the University of Bergen in Norway. In Swedish Sign Language, for example, listeners often sign yes as a continuer for long stretches, but to keep this continuer unobtrusive, the sender tends to hold their hands lower than usual.

Different interjections can send slightly different signals. Consider, for example, one person describing to another how to build a piece of IKEA furniture, says Allison Nguyen, a psycholinguist at Illinois State University. In such a conversation, mm-hmm might indicate that the speaker should continue explaining the current step, while yeah or OK would imply that the listener is done with that step and it’s time to move on to the next.

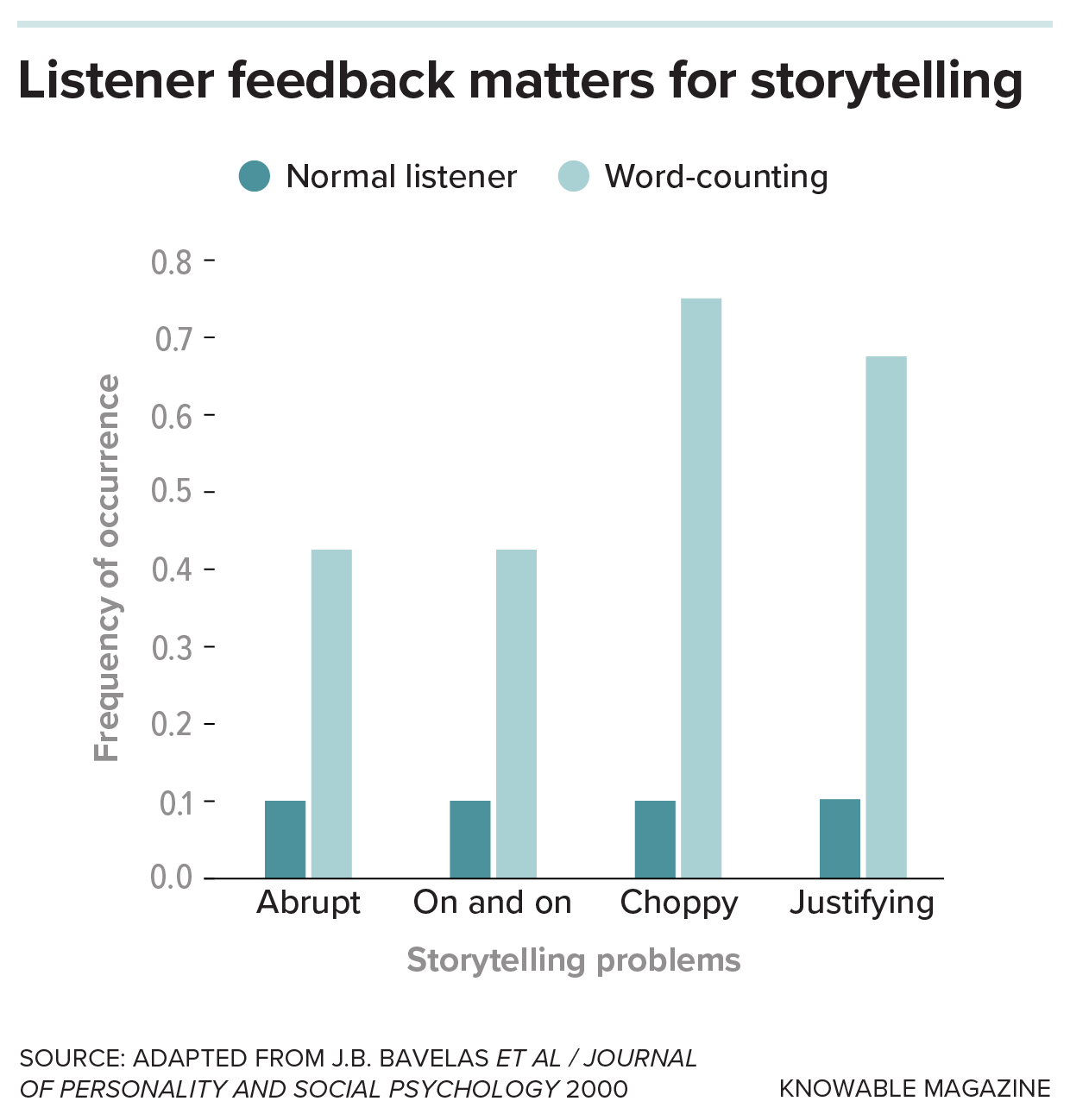

Continuers aren’t merely for politeness — they really matter to a conversation, says Dingemanse. In one classic experiment from more than two decades ago, 34 undergraduate students listened as another volunteer told them a story. Some of the listeners gave the usual “I’m listening” signals, while others—who had been instructed to count the number of words beginning with the letter t—were too distracted to do so. The lack of normal signals from the listeners led to stories that were less well crafted, the researchers found. “That shows that these little words are quite consequential,” says Dingemanse.

Nguyen agrees that such words are far from meaningless. “They really do a lot for mutual understanding and mutual conversation,” she says. She’s now working to see if emojis serve similar functions in text conversations.

The role of interjections goes even deeper than regulating the flow of conversation. Interjections also help in negotiating the ground rules of a conversation. Every time two people converse, they need to establish an understanding of where each is coming from: what each participant knows to begin with, what they think the other person knows and how much detail they want to hear. Much of this work—what linguists call “grounding”—is carried out by interjections.

“If I’m telling you a story and you say something like ‘Wow!’ I might find that encouraging and add more detail,” says Nguyen. “But if you do something like, ‘Uh-huh,’ I’m going to assume you aren’t interested in more detail.”

A key part of grounding is working out what each participant thinks about the other’s knowledge, says Martina Wiltschko, a theoretical linguist at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Barcelona, Spain. Some languages, like Mandarin, explicitly differentiate between “I’m telling you something you didn’t know” and “I’m telling you something that I think you knew already.” In English, that task falls largely on interjections.

One of Wiltschko’s favorite examples is the Canadian eh? “If I tell you you have a new dog, I’m usually not telling you stuff you don’t know, so it’s weird for me to tell you,” she says. But You have a new dog, eh? eliminates the weirdness by flagging the statement as news to the speaker, not the listener.

Other interjections can indicate that the speaker knows they’re not giving the other participant what they sought. “If you ask me what’s the weather like in Barcelona, I can say ‘Well, I haven’t been outside yet,’” says Wiltschko. The well is an acknowledgement that she’s not quite answering the question.

Wiltschko and her students have now examined more than 20 languages, and every one of them uses little words for negotiations like these. “I haven’t found a language that doesn’t do these three general things: what I know, what I think you know and turn-taking,” she says. They are key to regulating conversations, she adds: “We are building common ground, and we are taking turns.”

Details like these aren’t just arcana for linguists to obsess over. Using interjections properly is a key part of sounding fluent in speaking a second language, notes Wiltschko, but language teachers often ignore them. “When it comes to language teaching, you get points deducted for using ums and uhs, because you’re ‘not fluent,’” she says. “But native speakers use them, because it helps! They should be taught.” Artificial intelligence, too, can struggle to use interjections well, she notes, making them the best way to distinguish between a computer and a real human (see box ).

And interjections also provide a window into interpersonal relationships. “These little markers say so much about what you think,” she says — and they’re harder to control than the actual content. Maybe couples therapists, for example, would find that interjections afford useful insights into how their clients regard one another and how they negotiate power in a conversation. The interjection oh often signals confrontation, she says, as in the difference between “Do you want to go out for dinner?” and “Oh, so now you want to go out for dinner?”

Indeed, these little words go right to the heart of language and what it is for. “Language exists because we need to interact with one another,” says Börstell. “For me, that’s the main reason for language being so successful.”

Dingemanse goes one step further. Interjections, he says, don’t just facilitate our conversations. In negotiating points of view and grounding, they’re also how language talks about talking.

“With huh? you say not just ‘I didn’t understand,’” says Dingemanse. “It’s ‘I understand you’re trying to tell me something, but I didn’t get it.’” That reflexivity enables more sophisticated speech and thought. Indeed, he says, “I don’t think we would have complex language if it were not for these simple words.”

Keep up with the week’s essential science news headlines, plus stories that offer extra joy and awe.

Bob Holmes is a contributing writer for Knowable Magazine based in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. I once got a phone call from someone who wanted to use Science Friday to teach English as a second language. I said I was so glad to hear that she wanted to use science to teach English.

Well, there was a long pause. And she said, actually, I like the way you interrupt people. Yeah, I do that a lot, don’t I? Or I interject often to move the conversation along.

What I recently learned is that interjections are an important part of our conversations and have been studied quite a bit. Joining me now to tell us more is my guest, who recently wrote all about the role of interjections for Knowable Magazine. Bob Holmes is a science journalist based in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Welcome to Science Friday.

BOB HOLMES: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. OK, so you’ve written about the role of what linguistics call interjections. Can you define them for me?

BOB HOLMES: Well, basically, they’re short utterances, usually a single word that aren’t part of sentences and don’t really convey specific information the way a sentence does. Linguists used to think they were the detritus that accumulates around the edges of conversations. When we’re not as articulate as we want to be, we say “um” and those sorts of things.

But it’s turning out that they’re actually doing a lot more than, that they’re important traffic signals for keeping conversations flowing and for lining up what you and I actually want out of a conversation.

IRA FLATOW: Uh-huh.

BOB HOLMES: Exactly, yeah, “uh-huh,” that’s an interjection. It’s called a continuous.

IRA FLATOW: I did it again there.

BOB HOLMES: Yep. And it encourages the talker to keep going. Basically you’re saying, yeah, I’m with you. Let’s go. And that turns out to be really important. There’s a wonderful experiment that was done some years ago where the researchers had volunteers tell each other’s stories.

And sometimes, the listener was just told to listen. But other times, the listener was told to count the number of words with the letter T in them. And that meant that the listener was paying very close attention. But they were so busy figuring out what did that start with the T that they neglected to give the usual “mm-hmms” and “ooh,” those kind of little interjection feedback.

And it turned out that the speakers couldn’t talk nearly as well without those continuers going that they rambled on, or they cut their story short abruptly, or they overexplained things or under-explained things. It really dramatizes how important those are to storytelling.

IRA FLATOW: Huh.

BOB HOLMES: You need that feedback to tell it properly. Yeah, and there’s another good example, “huh.”

IRA FLATOW: That’s a good example. Why is that such a good example?

BOB HOLMES: Well, “huh,” especially the rising “huh?” is what they call a repair initiator. It signals that something went wrong with the conversation. I didn’t quite get what you were trying to tell me, and we need to stop and fix that.

And it turns out that every language ends up with something very similar because it’s basically the shortest syllable you can get out. “Huh?”

IRA FLATOW: Right. Is right another one?

BOB HOLMES: Yeah, it’s probably is. Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: So beyond traffic signals– when to keep going, when to pause– tell me about some of the other roles of interjections.

BOB HOLMES: Well, the other big role besides regulating whose turn it is and those sorts of things, is what linguists call grounding, which is basically when we start a conversation, we kind of have to negotiate between ourselves what you knew ahead of time, and what I knew ahead of time, and what you want out of the conversation, And what I want out of the conversation. So we’re figuring out where each other is coming from.

And these sorts of interjections are often important in that, too. One example would be if you were to ask me what the weather was here in Edmonton, I might say, well, I haven’t been outside yet. And the “well,” which isn’t really part of the information content of what I said, is essentially a flag that says, I know I’m not answering the question you asked, but it’s because I haven’t been outside yet, so it’s helping with the grounding.

IRA FLATOW: Being Canadian, I have to ask you about the Canadian “eh.”

BOB HOLMES: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me, is that special?

BOB HOLMES: It is. It does a lot of things, actually. But one of the things it does is to flag essentially my knowledge about your knowledge. If I organize a surprise birthday party for you, and you come in the door and all your friends jump out and say surprise! it would make no sense for me to say to you, what a surprise? Because I’m not surprised. I organized the party.

But it’s perfectly OK to say what a surprise, eh? Because the eh flags that I knew this, but you didn’t. And so it’s a marker to help us indicate our knowledge about one another’s knowledge. And actually, some languages do this with proper grammar. Mandarin Chinese apparently has a different grammatical structure for I’m telling you something that I don’t think you know, or I’m telling you something that I think you do know already.

IRA FLATOW: So all languages you’re saying have some sort of interjections?

BOB HOLMES: Yeah. Yeah, and they’re all doing pretty much the same thing. There’s continuers. There’s repair requests. There’s “um” placeholders.

IRA FLATOW: Now, what about sign languages? I mean, do signers use interjections?

BOB HOLMES: They do. They do.

IRA FLATOW: They do?

BOB HOLMES: Yep. So I mentioned earlier that “um-hmm” is a really good in spoken language because it’s unobtrusive, yet your mouth is closed. So you’re clearly not intending to speak. What you do if you’re signing a continuer, you sign yes often. And you sign it down low with your hands in your lap instead of up, sort in front of your chest. So again, it’s an unobtrusive signal that, yes, I’m paying attention. Keep going.

IRA FLATOW: Who knew? Wow, thank you. Even AI-generated audio slips in a few interjections. You asked Google LM to generate a podcast about interjections, and here’s a clip of what happened.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

– People have kind of dismissed interjections as primitive–

– Yeah.

– –as outside of proper language.

– Mm-hmm.

IRA FLATOW: Like, back in the 1700s, this guy, John Horne Tooke.

– Oh.

– He didn’t call them–

[END PLAYBACK]

IRA FLATOW: To me, it sounds pretty impressive, considering it’s AI. But here’s what linguistics researcher Martina Wiltschko makes of it.

MARTINA WILTSCHKO: My first impression when I listened to this was like looking at those AI-generated pictures where at first sight they look good. But on closer inspection, there is one finger too many, or something is off.

IRA FLATOW: Bob, so what’s off here?

BOB HOLMES: I agree. It sounds really good to me, too. But once Martina pointed it out, there are little tiny tells there. Like, when the listener says mm-hmm, the speaker pauses for that, and we don’t do that in normal conversation. The “mm-hmm” just sort of comes over the top of things. So the timing is not quite right.

And if you listen to a longer clip, also, it turns out that the who knows what part, the grounding, is confused too, because occasionally, first, the man seems to know what’s going on, and the woman is asking him for explanation. And then after a while they switch, and the man starts asking the woman for explanation. The AI doesn’t really understand who knows what.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. See, I’m doing it here again myself. I am certainly going to be more aware of this now that you have pointed this out. And after your reporting, you must be also.

BOB HOLMES: Yep, it’s definitely made me more self-conscious about “uh-huh” and things like that.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Bob, thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today.

BOB HOLMES: Happy to do it.

IRA FLATOW: Bob Holmes, contributing writer at Knowable Magazine, based in Alberta, Canada.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.