How To Close Gaps In Healthcare Access

25:37 minutes

When a public health crisis strikes, a natural instinct is to turn to a strong leader. The COVID-19 pandemic is a prime example: We want someone who can calm our fears, tell us what to expect, and what steps we can take to make things better. But leadership does not happen overnight—and it will take a brave person to step into the shoes that guide the country through the next stage of the pandemic.

Dr. David Satcher is used to adversity. Born into poverty in Anniston, Alabama, Satcher contracted whooping cough at two years old. The town’s only Black doctor, Dr. Jackson, treated Satcher, but did not expect him to live. Overcoming this illness launched him into a lifetime of public health work, with an emphasis on health equity.

Satcher speaks to Ira about his work as former assistant secretary for health, surgeon general of the U.S., and director of the Centers for Disease Control under Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. They also discuss his leadership work at the Morehouse School of Medicine, and his advice for getting the country towards a more equitable healthcare system.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

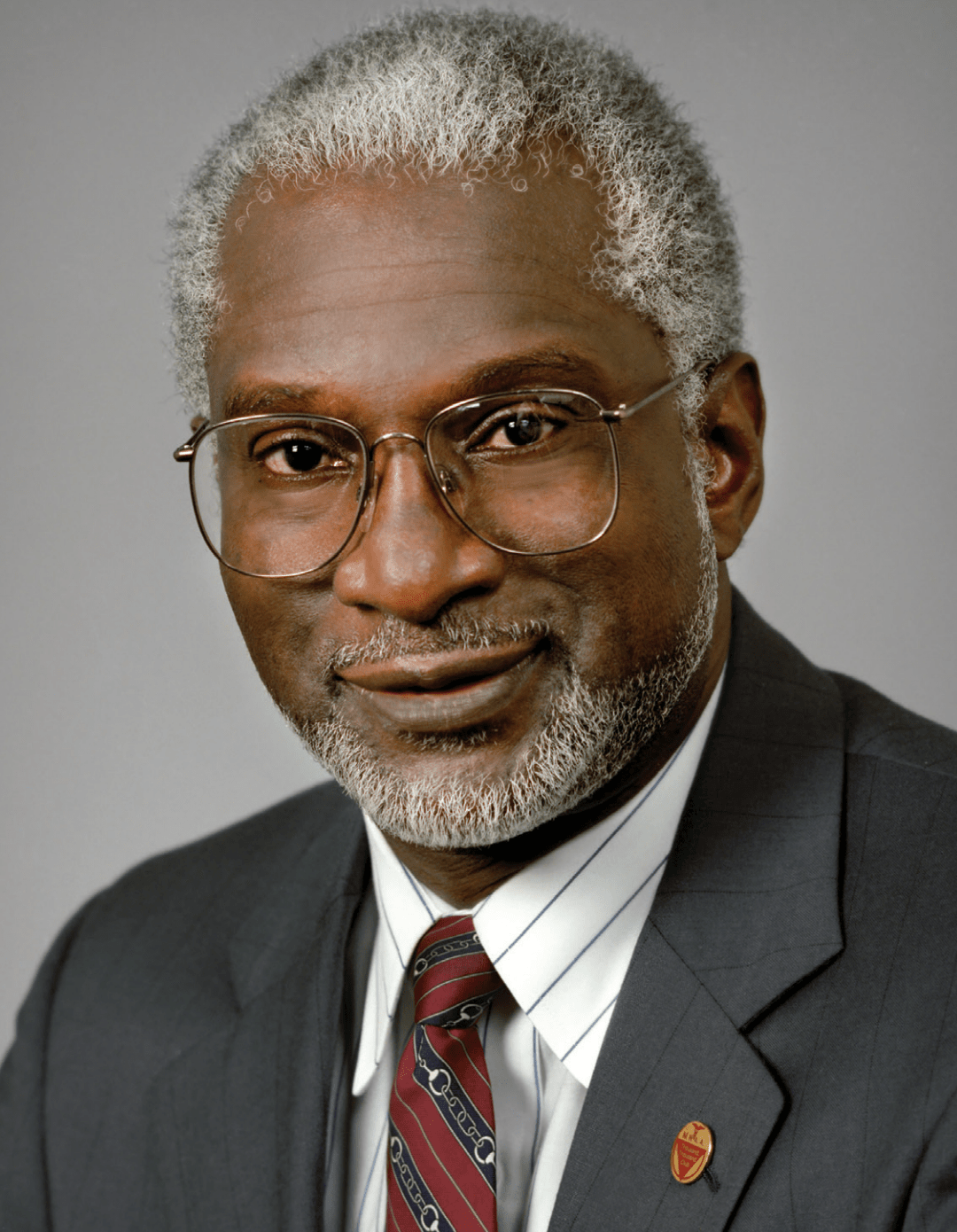

David Satcher is the former Surgeon General, CDC Director, and Assistant Secretary of Health, and is author of My Quest for Health Equity. He’s based in Atlanta, Georgia.

IRA FLATOW: When a public health crisis strikes, a natural instinct is to turn to a strong leader. Just think of this COVID pandemic– we want someone who can calm our fears, who can tell us what to expect next, and the steps we can take to make things better.

But leadership does not happen overnight. And it can take a brave person to step into the shoes that will guide a country and an idea. My next guest has a long and storied history of public health leadership. His new book, My Quest for Health Equity– Notes on Learning While Leading, is out now in paperback. I’m very pleased to Welcome Dr. David Satcher, former assistant secretary for health, former surgeon general and director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, founding director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAVID SATCHER: Good morning, Ira. It’s great to be with you.

IRA FLATOW: Nice to have you. Let’s talk about your personal history, because in your book, you refer to it many, many times. Your personal history with health equity started very early, when you were, what, just a toddler?

DAVID SATCHER: Yes. I had a very serious experience with whooping cough before I was two years of age. And I know it was serious because the one Black doctor in Anniston who came out to the farm to see me told my parents that he didn’t expect me to survive the week. And so that’s the story that they always tell, it’s that I was not expected to live. And my mother feels very proud of– or felt very proud of the fact that she was able to take care of me through this threat to my life.

IRA FLATOW: And that doctor who treated you–

DAVID SATCHER: Dr. Jackson.

IRA FLATOW: And that Dr. Jackson who treated you left a big impression on you about what you did with your life, correct?

DAVID SATCHER: Very much so. I never actually met him after I became old enough to know people, so I don’t remember the interactions. But by the time I was four years of age, my mother was talking about Dr. Jackson and the fact that he came out there and that he didn’t think I was going to live.

IRA FLATOW: Did that set you to thinking about becoming a physician yourself?

DAVID SATCHER: By the time I was six years old, I was telling everybody that I was going to be a doctor like Dr. Jackson. Clearly, because my mother talked so much about Dr. Jackson and the fact that he gave up his off day and came out to the farm and he worked so closely with them, and as a result, I survived that struggle with whooping cough and pneumonia.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s talk a bit about your educational history, because you mention in your book how important you believe education is. Neither of your parents finished elementary school. They made education a priority for you and your siblings. Tell me about your educational journey as a young Black man.

DAVID SATCHER: Well, it was quite a journey. I had eight siblings, and we all went to school. And we were told that education was a priority, that we were not going to be kept out of school to work on the farm. We had to do the work after we got home and before we left for school. We had to do the work on the farm. Each one of us had an assignment, but we couldn’t do it at the cost of education.

IRA FLATOW: And you believe that education is key to leadership and getting ahead in life.

DAVID SATCHER: I do. I think education is one of the greatest opportunities that we have when it comes to the things that determine our future. We now call them the social determinants of health. And certainly, education is one of the major social determinants of health. So we were taught to take it seriously.

I think it had something to do with the fact that my dad– who never actually finished the first grade but learned how to read, and my mother coached him– he went on to become superintendent of the Sunday school for 25 years. And he demanded that we study our lesson and that we’d be able to discuss it every Sunday. So as you can see, my parents were very serious about education.

IRA FLATOW: And you talk about these social determinants throughout your book. I want to get to that in a little bit later, but I want to talk about you writing that you, quote, “I have been a victim of racism and segregation, and I have had the opportunity to confront racism.” You participated in the Civil Rights Movement alongside the King family. How did that experience shape your idea of what a leader is?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, I was greatly inspired and motivated by Martin Luther King, Jr. As a student at Morehouse, I had many opportunities to hear him speak. A group of us, about five of us, would actually walk the five miles to Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he was a co-pastor with his father.

Now, this was later, and he had done the Montgomery bus boycott, and he was back in Atlanta. And we would go to hear him speak. And I’ve been quoting him ever since. He was one of the most quotable people I’ve ever met.

IRA FLATOW: And you quote him, and you say he has an unusual ability, quote, “to educate, motivate, and mobilize people.” Important talents for leaders to have.

DAVID SATCHER: Yes. Now, I watched the Montgomery bus boycott from afar. I was in Anniston, Alabama, 100 miles away. But my brother Robert, Bob, who is 3 and 1/2 years older than I am, he would come home and talk about the Montgomery bus boycott. He would go to Dexter Avenue Baptist Church on Sunday and hear Dr. King speak, and then he would get out and walk, join the boycott. As you know, that was one of the most successful civil rights interventions that we’ve ever had in this country. And it was the beginning of Martin Luther King’s journey as a leader.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. And you say that civil rights– and now I want to get back to what you mentioned before, health equity– are intertwined. Please explain what you mean by that.

DAVID SATCHER: Well, health equity is critical. And I say that because health equity is not having equal access. It is getting what you need to be healthy. And certainly, one of the biggest challenges that we face as a people, and that many people still face, is the inability to receive the care that they need. And so I have worked very hard throughout my life and career to find out, what is it that people really need to be healthy?

And we don’t all need the same thing. But we all need the opportunity to make the best of our own health. And that means having access to quality health care, which is so, so rare for so many people in this country.

IRA FLATOW: And how do we get there? How do we get health equity in this country?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, number one, I think it’s really critical for us to understand that health equity is important for the nation, not just for the people who are trying to get in the door. It is interesting, though, that the United States is one of the rare countries that apparently doesn’t see health equity as important to the extent that we make sure that everybody has access to it. And so that’s an ongoing struggle as we educate more physicians, more nurses, more public health leaders, getting people to realize that it is in the nation’s best interest to provide health equity and for people to be able to realize the optimal health status for themselves.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re continuing our conversation with Dr. David Satcher, former assistant secretary for health, former surgeon general, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. His new book, My Quest for Health Equity– Notes on Learning While Leading, is out now in paperback.

Speaking of showing leadership as a physician, you were a pioneer for Black physicians. And for some, you may have been the first prolific Black government physician they were ever exposed to. Do you feel a responsibility to be a good role model for other people?

DAVID SATCHER: I do. Yes. I’ve felt that for a long time. I think being around people like Dr. King and Benjamin Mays, who was president at Morehouse College, and others, you’re really challenged to think about, why are you here? What’s your role in life? What’s your responsibility?

So yeah, I do– I’ve always felt that I’m looking, always, for the best way to live up to my responsibility to other people. I can’t see children not getting access to health care and feel like I don’t have a responsibility. I do. As long as poverty is a major health problem, public health problem, then we’re all responsible.

IRA FLATOW: You write that you carry with you the sayings of Dr. Benjamin Elijah Mays, whom you’ve talked about at Morehouse. And those sayings include, quote, “The tragedy in life does not lie in not reaching your goal. The tragedy lies in having no goal to reach.”

DAVID SATCHER: Wow, right on target, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You wrote it. [LAUGHS] Do you feel that you have reached your goal?

DAVID SATCHER: No, by no means. I’ve reached a lot of goals, but not my goal, because I think my goal must be to make health care available to all people, not just in this country. It’s really sad to be able to– to have to say that it’s not available to all people in this country. It still often depends upon where you live, where you work, how much money you have. And I think that’s an issue.

The reason that I have put so much emphasis on public health in my career, even though I trained in medicine and pediatrics– I went into public health because I think the definition of public health fits me. It says that public health is the cooperative efforts of a people to create the conditions in which people can be healthy. In other words, public health is not just about getting health care. It’s about dealing with the conditions that make people sick in the first place.

IRA FLATOW: And you say that, to many people, public health means just seeing a good doctor. But you write that, no, it involves good nutrition, a good place to live. There are other environmental factors that contribute much more to public health than just access to a good doctor.

DAVID SATCHER: No question about it. Public health recognizes that, number one, we are a community. And in this community, we have a responsibility for each other. And we have to find a way to make sure that the conditions– and I want to repeat that word again, because it takes us back to the social determinants of health. Public health is the cooperative efforts to create the conditions in which people can be healthy. The conditions.

And some people don’t have those conditions. From birth to death, they live in conditions that are not conducive to good health. And so part of what we do together is to try to change those conditions. So it’s not just about medical care. It’s about creating conditions where people can live healthy lives.

Now, many people remember that as surgeon general, one of the first things I did was to develop the surgeon general’s prescription. And the things on this prescription are pretty simple– moderate physical activity at least five days a week, 30 minutes a day, eating at least five servings of fruits and vegetables, avoiding toxins, including tobacco. So those are the kinds of things– responsible sexual behavior, daily participation in relaxing and stress-reducing activities. So I don’t believe that health care or good health is just a system responsibility. I think it starts with individuals. But somebody needs to educate individuals.

IRA FLATOW: Do you think we’re doing an adequate job at that educational process?

DAVID SATCHER: No, we’re not. I mean, it’s one of the weaknesses of our system. And I think, in the system, we are often rewarded because we don’t do a good job. I guess during the time that I was surgeon general, and really before, people heard me talk about that our system of health care created disparities in health. And so the whole issue of eliminating disparities became a big issue starting in 2000, when we released a plan, the Healthy People 2010. But that commitment to closing the gap, to eliminating disparities in health, was based on the fact that we felt that these were disparities that we helped to create.

Now, when we talk about COVID-19, it’s very clear that there are some people who are going to have an experience with COVID-19 that’s different from others. And as a rule, they’re going to get COVID-19 more frequently, and they’re going to die earlier. They’re going to be more likely to be hospitalized.

And when you look at it, it’s mainly because they had risk factors. Health disparities are risk factors. And so go look at the people who are in the hospital, those who have been there, those who have died. And what you find is that they came to this pandemic, if you will, at greater risk than others.

IRA FLATOW: So what do you think it will take in terms of leadership, in terms of motivation, in terms of action? What kind of actions are going to be able to change these disparities?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, number one, I think, as a rule, systems in this country operate effectively when desired behavior is rewarded. And we certainly need to do a better job of rewarding people who serve valiantly on the front lines of health care, to not just keep people alive, but to keep people healthy.

When I say reward, I’m not just talking about money. Reward people who do a good job on the front line of health care, people who are often completely ignored, neglected. Front-line workers who, with a little help, would keep many more people alive. And yet even without that help, they’re doing a great job.

So front-line workers. Nurses– I know that physicians don’t like to think of nurses as being at the leadership of the health care system, but nurses really, not just in the hospitals where there are COVID patients, but in many other settings, nurses serve valiantly. And they die because of this kind of service that they provide. And we’ve seen that in this pandemic.

IRA FLATOW: What about training physicians to better understand what these other factors of health are?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, I think that that’s sort of where it begins for me. I think I went to medical school already feeling very strongly the obligation that physicians had. And for me, it goes back again to Dr. Jackson. It goes back to knowing that if physicians were on the front line of care, and they took risk and more and more, we would see people who don’t have access to care getting access to care, quality health care.

So I think physicians have a leadership responsibility. And that’s not to say that all of the leaders in health care should be physicians. But it says that physicians have a leadership responsibility when it comes to health and health care, one that we haven’t always carried out. And that should change.

IRA FLATOW: And what do you think of the current state of COVID leadership in this country?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, COVID has been one of the major challenges that we have faced. Now, the question becomes, when there are pandemics, how do we respond as a global community? Because pandemics are not the challenge to any individual country. Pandemics, they don’t have boundaries, so they spread rapidly.

So we’re really fortunate, given the systems that we have in place, we’re fortunate that not more people have not died from this pandemic. And hopefully, fewer people will die in the future. But despite all of our resources as a global community, we’re not committed to working together in such a way. We’re fighting.

We’re not figuring out how to work together to prevent the spread of Delta and Omicron. And that’s what we have to do if we’re going to make sure that we’re not suffering from a new pandemic every other year. This is going to take cooperative effort to lead us into a healthier future.

IRA FLATOW: You mean, in other words, we need to be spreading vaccinations and health care to other countries as well as our own.

DAVID SATCHER: Oh, most definitely. And I commend the administration and others for the extent to which we have made vaccines available to other countries. We can do better. But certainly, we have seen our responsibility. We have made vaccines available to countries all over the world, Africa.

There’s no debate about the fact that we need to make vaccines available. The debate is more, why is it that certain people won’t take them? And that’s because we don’t trust each other.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, that’s a big issue you just brought up– trust. Trust. How do we restore trust, Dr. Satcher?

DAVID SATCHER: If I had the answer to that, then that’s what I would be doing all the time. But I do think it’s the appropriate question. How do we restore trust? We have a lot. I mean, we have we’ve been entrusted with the lot in terms of resources. And the question is, then, how do we use those resources to make the world a better place, where people trust each other, can work together?

IRA FLATOW: You’ve spent a whole part of your life, a great part of your younger life and later in life, trying to solve the distrust problem, the distrust people have for maybe their community leaders, the distrust they have for equity. I mean, distrust is a very difficult concept to overcome, isn’t it?

DAVID SATCHER: Oh, it is. I think– but there are also a lot of reasons for people to trust each other, because some good things have happened. In the book, one of the most difficult stories for me to write was that story about my walking out on the OB/GYN rotation and then being threatened to be put out of school. You know how hard I had worked to get to that point in my life, all through the cotton fields of Alabama and jails in Georgia. And yet that whole thing was threatened when I walked out.

IRA FLATOW: You tell this story in your book, and I think this is instructional, about your leadership, about how in medical school, you walked out of an OB/GYN exam because you felt the patients were not being treated appropriately.

DAVID SATCHER: I couldn’t honestly do anything else, because I can’t say, I have to participate in the mistreatment of patients because I want to be a doctor. I did want to be a doctor, but I couldn’t do that. And you know what happened. After I walked out and was told to go to see the dean the next day, with the implication that I was going to be dismissed from school, later that day, somebody– and I’m embarrassed that I can’t tell you the name of that student– called a meeting of the other students, nine other students. And they decided to walk out, also.

They decided that if it were inhumane for me to do it– and they agreed– then it was inhumane for them to treat patients that way. And so by the time I got to the dean the next morning, he said to me, David, do you know what happened this morning? I didn’t. And he told me the other students had walked out. Then he told me that the school was going to change the practice. Said we were right, and the school was going to change.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. What do you think that you inspired in those students to walk out with you?

DAVID SATCHER: Well, if I’d just assumed that because I grew up in poverty, because I’ve been to jail and prison fighting for rights, that I’m the only one who feels that way. So what those students proved– and it could have been just one or two students who provided the leadership. I never analyzed, how did it happen? I just know that they came together and decided that if I was going to be put out for walking out, they were going to join me.

And I don’t know. I just think that we often underestimate people. And I believe that we have to trust people to be their best selves.

IRA FLATOW: One final question for you, Doctor. Over the last 10 years, I know you’ve become involved, you write, in developing the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at the Morehouse School of Medicine. Give me an idea, if you can, of the goal of that institute and your work there.

DAVID SATCHER: Well, first, I mean, I was concerned that not enough support is being made available for leadership development. This quote tells you a lot, and it is the Satcher Health Leadership Institute’s quote. When we talk about the kind of people that we’re trying to help develop, we need people, on the one hand, who care enough. We believe that caring is the first need that we have for leadership development.

Secondly, people who know enough, and we hope that here at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute, we can help to provide people with a base of knowledge that will help them to be better leaders. We need people who have the courage to do enough, and that gets back to that experience at Case Western and people taking chances. And many of them didn’t even know me personally, but when they heard the story, they said they agreed.

And finally, we need people who will persevere until the job is done. Perseverance is critical, because nothing like this is going to happen overnight. And Martin Luther King, Jr., knew that. And in fact, he didn’t think it would happen in the 40 years that he lived. And so he didn’t go into this thinking that one day there was going to be a celebration and he was going to win another Nobel Prize. No, he went into it knowing that he was probably going to be killed. And he was.

IRA FLATOW: Well, Dr. Satcher, I want to thank you for your life’s effort and for taking time to be with us today. And good luck to you.

DAVID SATCHER: Thank you very much, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. David Satcher, former assistant secretary for health, surgeon general, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia. His new book, My Quest for Health Equity– Notes on Learning While Leading, is out now in paperback. And you can read an excerpt from the book on our website, sciencefriday.com/healthequity.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

A selection of Science Friday’s podcasts, teaching guides, and other resources are available in the LabXchange library, a free global science classroom open to every curious mind.

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.