What El Niño Means for Other Parts of the Planet

26:37 minutes

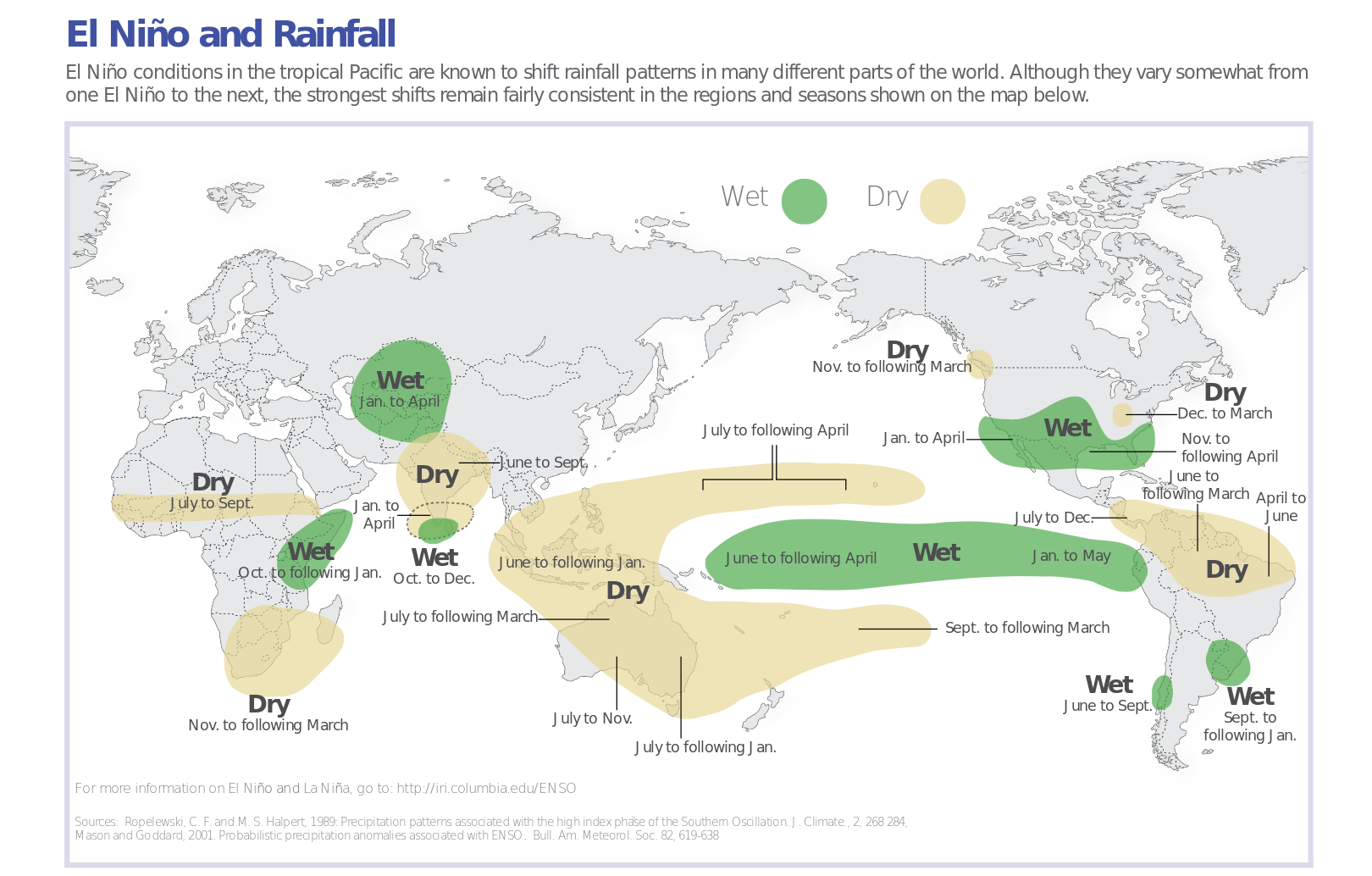

When you hear about El Niño in the news in our country, the focus is usually on one thing: rain in the southwestern U.S. El Niño’s atmospheric influence stretches around the world, depleting fish stocks off Peru, affecting the incidence of snakebites in Costa Rica, and potentially driving up malaria deaths in East Africa. Ira and guests discuss the global impacts of the climate cycle, and how they might give us clues to the public health effects of a warming world.

Andy Hoell is a NOAA meteorologist in the Earth System Research Laboratory’s Physical Sciences Division in Boulder, Colorado.

Aaron Bernstein is Associate Director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Madeleine Thomson is a senior research scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, and is director of the World Health Organization collaborating center on climate-sensitive diseases. She’s based in Palisades, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. When you hear about El Nino in the news, the focus is usually on one thing.

SPEAKER 1: The storms this past week are fueled by an El Nino.

SPEAKER 2: We had our first really good soaking in almost five years.

SPEAKER 3: El Nino can bring storms, that’s what it’s been doing this month.

SPEAKER 4: Scientists have been doing forensic work to learn what set this huge storm in motion. They say they think the trail starts with the weather pattern, called El Nino.

IRA FLATOW: Like in that clip, the focus of El Nino is usually storms and weird weather here in the United States. And hey, you can’t blame people for paying attention to where they live. But El Nino is a truly global climate phenomenon which affects all people all over the world.

I was just down in Costa Rica, for example, where everyone was talking about the massive drought they’re experiencing during this El Nino cycle. And that’s, of course, a flip side to all that rain in California. And El Nino’s atmospheric influence stretches all the way through South America over to Africa, even Southeast Asia. So this hour, we wanted to take stock of what El Nino means, depending on your place on the planet.

And if you’re unsure what exactly El Nino is or why it even comes and goes, we’re going to start off with a little refresher course from Andy Hoell. He’s a NOAA meteorologist at the Earth System Research Laboratory, Physical Science Division in Boulder, Colorado. Welcome to Science Friday, Dr. Hoell.

ANDY HOELL: Hi, Ira. Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s start with El Nino. What’s the thumbnail definition? Give us a little background.

ANDY HOELL: Sure. El Nino is one phase of the El Nino Southern Oscillation. The El Nino Southern Oscillation is characterized by a shift in warm water across the Tropical Pacific Ocean and the associated winds alongside that. During El Nino, warm water from the West Pacific Ocean shifts eastward toward the Central Pacific Ocean. So the normally cool Central and Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean become anomalously warm.

Some El Nino events are well predicted. This El Nino is a good example of that. On the other hand, some El Nino events are poorly predicted, and the forecast El Nino of last winter that didn’t materialize until March is another good example. This shows that, as a scientific community, we have a lot to learn about the physics of El Nino.

Currently, we’re learning a lot more about the physics of El Nino through NOAA’s El Nino rapid response field campaign. And our rapid response field campaign is taking observations of the Tropical Pacific using various assets, that include airplane ships, buoys, satellites, and models.

IRA FLATOW: Does it extend up and down the whole America’s coastline? North, South America?

ANDY HOELL: The expression of El Nino is typically tropically confined, but with the global impacts– so El Nino, even though it’s characterized by changes in sea surface temperatures and those associated winds over the tropics, we see big changes in the tropical climate that then influence the rest of the climate. So you can think of it like this. So when we see an El Nino event, like we’re having right now, we get precipitation, enhanced precipitation over the tropical Central Pacific Ocean. And the effect of the enhanced Tropical Pacific Ocean precipitation causes the formation of clouds, and therefore rainfall, and that releases a lot of energy to the atmosphere.

So that energy released to the atmosphere, it behaves similar to dropping a stone in water. And what that does is it creates waves that then move away from the source of that stone moving in the water. And that’s what we see here in our climate system. And we see these waves move away in a somewhat of a predictable way.

IRA FLATOW: Do we know why El Ninos begin and end?

ANDY HOELL: We have hypotheses to constrain that, but we have a lot more to learn, obviously, in terms of the way El Ninos begin and then mature. And that makes– it’s very difficult. We have a hypothesis called the delayed oscillator hypothesis that needs to be further explored.

IRA FLATOW: Do we have any connection to global warming?

ANDY HOELL: It’s interesting. There have been a number of studies in the last couple years, and these studies focus on two things. The first one is that it looks at how the El Nino itself behaves under global warming, and there’s increasing evidence that there are more El Nino and La Nina extremes associated with that. La Nina’s just the opposing phase of El Nino within the ENSO cycle.

There’s also another complicating factor here is the background climate is changing as well. So the Pacific Sea surface temperatures are generally warming and alongside that associated with El Nino, we see enhanced impacts. And we’ve actually seen that during the recent La Ninas. So there’s a lot more that we need to learn in terms of how the global warming effect is impacting El Nino.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you for that primer, Andy. It was highly education. Andy Hoyle is a NOAA meteorologist at the Earth System Research Laboratories Physical Sciences Division in Boulder, Colorado. Thanks for joining us.

ANDY HOELL: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. OK, now that we know the ABCs of El Nino, we can delve into its consequences around the world with a couple of scientists who study El Nino effects on people, making or breaking a years harvest, flooding coastal cities, or maybe driving a bumper crop of disease carrying mosquitoes. Madeleine Thomson is a Senior Research Scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Sociology in Palisades, New York, and director of the WHO collaborating center on climate sensitive diseases. Welcome to Science Friday.

MADELEINE THOMSON: Thank you very much.

IRA FLATOW: Aaron Bernstein is associate director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard. Welcome to Science Friday. Dr. Thomson, let me ask you. Give us a snapshot of some of the things happening in other parts of the world now due to El Nino.

MADELEINE THOMSON: Well, the El Nino emerged for 2015 really in May last year, and it has been impacting on the climate, particularly on the tropical climates, since then, according to the timing of their rainy seasons. And more generally, the impact on temperature has been persisting throughout the year. And we while we still have a strong El Nino going at the moment, we expect that to dissipate in the next few months. But the impacts on health and on communities around the world will continue way beyond that, just because of the way that climate impacts on society, impacts on food security, and impacts on vector-borne diseases with a certain amount of delay sometimes.

IRA FLATOW: You know, it sounds almost surprising that an El Nino can go all the way over to Africa, effect malaria there, or the Rift Valley fever in East Africa, fires in Indonesia. It’s amazing something so far away can have such a ripple effect.

MADELEINE THOMSON: It is extraordinary, and I’m coming from the non-climate background. And it’s been something that’s been a fascinating journey for me to understand the importance of El Nino in driving–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

MADELEINE THOMSON: –health issues around the world. And I think really in the last decade, the health community has started to understand that it’s important to really be able to factor in El Nino and other climate issues into health preparedness, really trying to make sure that control programs are well organized in time to deal with unusual events like this.

IRA FLATOW: Aaron Bernstein, some studies have linked El Nino to cholera cases in Bangladesh. Is that right?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Where was it?

IRA FLATOW: Aaron Bernstein, can you hear me? Well, I guess he’s having trouble hearing me. Aaron Bernstein, are you there? Well, let me continue with Madeleine while we get him squared away.

AARON BERNSTEIN: Can you hear me now?

IRA FLATOW: I hear you. Can you hear me?

AARON BERNSTEIN: I can.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Magic of live radio. Let me ask you about the possibility that– I understand that El Nino may be linked to cholera cases in Bangladesh. What’s going on there?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Sure, so dating back a few decades now, starting with some of Rita Colwell’s work, there was a suspicion the temperatures in the Bay of Bengal, which is near Bangladesh, would drive the likelihood of cholera. And over time, that hypothesis has been explored, and it seems from experience that cholera outbreaks are more likely to occur in El Nino years. And that’s perhaps not surprising, because those cholera epidemics in part are driven by what are called copepod populations. These are small animals living the ocean that harbor the bacteria, and they do quite well in warmer waters.

IRA FLATOW: There was a story in the New York Times the other day about the dengue outbreak in Argentina. Any possible links to El Nino?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Yeah, so there is research also showing that dengue outbreaks are more common in Argentina during El Nino years. And so it’s not terribly surprising to hear about that outbreak.

IRA FLATOW: Couldn’t we link it to the outbreak now in the Zika virus?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Well, the same mosquito transmits Zika and dengue, so those mosquitoes are likely benefiting from El Nino conditions. Now, the presence of Zika in South America itself is a separate question, because it’s obviously new to that continent.

IRA FLATOW: Madeleine Thomson, do developing countries have access to all this data and analyses that the developed countries have about El Nino and the spreading of disease?

MADELEINE THOMSON: No. They clearly don’t. But I think one of the opportunities, if you like, created by El Nino is that it substantially is– influences the climate in the tropics and it makes that climate more predictable. So populations in the tropics often are poorer and more vulnerable to climate events and more exposed, if you’d like, to infectious disease, et cetera. But forecasts, all of the future climate the season ahead, work better in the tropics because of El Nino. So you’ve got sort of an advantage for poorer countries there as long as that information can be made available, and that information increasingly is being made available to affected countries.

Ethiopia, I think, is an excellent example where the government really understands how important climate is not only to it’s economy and its livelihoods but to disease issues, et cetera, and the development of epidemics. And they have been working very hard with meteorological services to get the predictions ahead of time, position resources ahead of events to try and alleviate the issues for the population. So I think that is really beginning to develop now.

IRA FLATOW: Aaron Bernstein, you’ve talked about using El Nino as a sort of real world experiment that gives us hints about what might happen under climate change.

AARON BERNSTEIN: Sure, yeah. I think that El Nino events, because they have such profound effects upon temperature and precipitation around the world, may give us a glimpse as to the kinds of risks for infectious diseases we might see in a warmer world with more intense precipitation cycles. And I can’t say that the kinds of patterns we see with infectious diseases during El Nino years are the kinds of patterns we’ll see as climate change unfolds, but what El Nino teaches us is that the diseases of humanity, and many of the ones we’ve talked about, are climate sensitive. And we cannot expect that as climate change continues to unfold that we’re not going to see nasty surprises of infectious diseases.

IRA FLATOW: How much money does– do we in the US government spend annually on studying El Nino? Is there a ballpark estimate of what percentage of the budget or the weather budget or the climate budget?

AARON BERNSTEIN: I think that there’s the piece which is the natural science piece, which is substantial, but the other question is do we understand the health pathways? And funding into the effects of climate change into health is really quite limited right now. In the NIH, for instance, which has a $32 billion budget at best, there’s probably 160 million or so, which would be less than a percent of the budget. EPA throws in another fair share, but the truth is that we can do a lot more to prepare the people we depend upon to protect us from potential nasty surprises by having more funding available to both understand and prepare for potential outbreaks.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. I’m talking about the health effects of El Nino.

You know, one scientist after another comes on this program and tells us, you know, we only react after there’s an emergency. We don’t spend any money really researching, whether it’s the Zika virus or whether it’s any other kind of disease that strikes until we’re hit over the head with it. Would you agree with that?

AARON BERNSTEIN: I think we have a habit as a species of being reactionary, but I’ve actually seen a lot that suggests we’re learning a different way of behaving with this stuff. I mean, we now have plans in place to do better when it comes to the drought we’re seeing in Ethiopia, to floods we’re seeing elsewhere in the world and trying to position aid in places that will offset potential humanitarian problems.

Now, we can obviously do more, but I’m heartened to see that we acknowledge that this is a real issue, and that we can anticipate problems. And I see that trend continuing. I think that aid organizations and governments have really understood that we can do a lot to lessen the potential health burden here.

IRA FLATOW: Madeleine, do agree with that?

MADELEINE THOMSON: Well, yes, and I think the other issue is that to really understand the value of systematic data collection. You can’t predict the future climate without understanding the past. You can’t enable new tools for predicting epidemics if people haven’t got good data to work with. And I think understanding the investments in health information systems, in climate data, et cetera, the importance of those investments for being able to manage risk is something that I think the public is beginning to understand. And I think we need to make politicians understand that, too.

IRA FLATOW: Let me see if I can get a quick phone call in here. Let’s go to Hans in the– is it Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin?

HANS: That’s correct.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there, go ahead.

HANS: Hi, thank you. So it’s not really a health question, but I was just curious about given where El Nino tends to start in the Pacific Ocean, if it has any sort of affect on the Hawaiian Islands, or if it sort of passes over them?

IRA FLATOW: Aaron, do you see any health effects, or–

AARON BERNSTEIN: I haven’t come across evidence to show that, but I’m not sure anyone’s looked particularly closely.

IRA FLATOW: And Madeleine, I’m sure you probably haven’t either.

MADELEINE THOMSON: Well, I think certainly in the Institute where I work where we have climate scientists who worked in the Pacific– very much so. I think that it’s likely that there’s predictability there. In fact, I know there’s a Climate Institute in Hawaii that’s focused very much on ENSO. So it must have a strong effect there, too.

IRA FLATOW: And I got about a minute before the break, but I want to talk about the flip side to El Nino, La Nina. Does that cancel out some of El Nino’s negative effects around the world? Madeleine?

MADELEINE THOMSON: It creates not exactly opposite conditions. I think the main thing about both La Nina and El Nino is that they create unsuaully– sort of departures from the average, if you like. So either wetter conditions from normal, or drier conditions form normal. And any disruption or change like that tends overall to have a negative effect, because economists, livelihoods, agricultural systems, if you like, established around norms. And when it’s– when you have an unusual situation, it’s more difficult to manage.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Talking with Madeleine Thomson, in case you’re just joining us, from the World Health Organization. Aaron Bernstein from Harvard, the Director of Center for Health and Global Environment at Harvard. Our number, 844-724-8255, if you’d like to call in and talk about El Nino and it’s a world effects. You can also tweet us @scifri. We’re taking tweets also. We have to take a break, but we will be right back so stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about El Nino where a lot of people think it’s a lot of rain in California, or dry desert some other place in the United States. But it is a worldwide effect, and it’s hard to believe how far around the world it affects disease and food security.

And I’m discussing that with my guests, Madeleine Thomson, Senior Research Scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society in Palisades, New York, a little bit up the Hudson here. Aaron Bernstein, Associate Director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard.

Our number 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri. Aaron, is El Nino going to get even stronger due to climate change or global warming?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Well, I think, as we heard from Dr. Hoyle, that there is some evidence to suggest that climate change may be influencing the strength of El Nino. That evidence is fairly preliminary, but as a pediatrician, as a clinician, I look at this situation as I would a young child in my care who had a fever and was looking fairly sick, and saying, it’s not really the wise choice to sort of watch and wait and see what happens. I would want to try and understand as best I could, and intervene if I knew how to intervene appropriately.

And that’s what we see here. We see potential catastrophes that are avoidable, and we know how to fix them. In medicine, we have problems that we can understand fully. We know very well how they manifest, but we have no means to treat them.

That’s not the problem of climate change. And if climate change is influencing El Ninos, which we know disrupt health systems and substantially harm people around the world, we really need to make sure we’re doing everything possible to prevent those harms.

IRA FLATOW: What I take that to mean– infer from what you’re saying, by treatment that is decreasing carbon emissions?

AARON BERNSTEIN: That’s right. I think that there’s no question that what the doctor orders in this instance is reducing our greenhouse gas contributions to the Earth’s atmosphere.

IRA FLATOW: Madeleine, is there general agreement about that around the world?

MADELEINE THOMSON: Yes, but one of things I’d like to add is even with the uncertainty, or maybe sort of like understanding of climate change impact on the El Ninos themselves, we know that it impacts on the actual impacts. And that is because if you have a drought in a warming world, then that drought is going to be more severe than in a cooler environment because of the increased evapotranspiration. So we know that even without changes in El Nino, a warming world is going to increase the impacts.

And then, like as have already been raised, there are questions that these events may become more and more severe. I think if you remember in COP21, the big conference in Paris for the climate treaty, there were very significant presence from the health community at that conference trying to ensure that health is really clearly understood as a major area of harm of climate change, but also an area of benefit for climate change mitigation. Because if we reduce carbon emissions, we know absolutely we can save lives, reduce asthma, all those other health problems that are associated with poor quality air.

IRA FLATOW: We had a question before from a listener about Hawaii, but we now have a listener from Hawaii, who’s calling in from Maui. Hi Tom, welcome.

TOM: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Give us an update on what you’ve experienced.

TOM: Yeah, so this past summer, I surfed a lot. And the water temperature here this summer was the warmest I’ve ever [INAUDIBLE] or felt it, and it lasted pretty far into the fall and into winter. And on top of that, really light winds which makes great surf conditions, as well as a lot of swells coming from both the South and North. So that’s something that we experienced from the last El Nino over here in Maui, and I’m sure on the rest of the Island.

IRA FLATOW: So that’s kind of a good thing for surfers then?

TOM: Definitely, yeah. We have a very positive impact as far as surfing, but I think that rainfall can be a lot lighter than normal.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. OK, well, there is a little bit of a– thanks for calling, Tom, and calling and giving us a surf report about El Nino. I guess there’s bigger waves. It’s a little warmer. And there is some effect on Hawaii, but we don’t know what the effect– he didn’t give us– he said it was a little drier.

MADELEINE THOMSON: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Would that be about right, Madeleine?

MADELEINE THOMSON: I think so, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: I think it is surprising that people here in the States, him talking from Hawaii, that it is very surprising to people. For example, we had a tweet in. Somebody was asking, we don’t have any monsoons here in the US. What kind of monsoons are you talking about?

MADELEINE THOMSON: I was talking about in the [INAUDIBLE] and Africa and the India monsoon.

IRA FLATOW: And where does that stand now?

MADELEINE THOMSON: What are the current–

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Are they getting more intense, or can you predict that they will be?

MADELEINE THOMSON: So at the moment, the monsoon for West Africa is over. It’s their dry season now. But we do know that El Nino does impact on the timing, the intensity of the rainy season. And in parts of the world, the rainy season is governed by monsoons.

IRA FLATOW: Well, let me ask this question in summing up. What don’t we know about El Nino that you as a worldwide planner would like to know more about? What do we need to know?

MADELEINE THOMSON: For me, the challenge is that we need to know really how it’s going to impact locally, because decisions about how to manage health issues are taken at many different levels. At the global level, regional level, national level, but at the local level is really where the rubber hits the road. And people need to understand their climate locally, how it’s influenced by factors such as El Nino, and may be influenced in the future by climate change.

And to have that local information, you have to be able to have local data that is managed and available to decision makers. And that I think is a big gap in many countries. It’s a gap that we’re trying to fill, but it’s a very important starting point to understand your local climate and understand its drivers.

IRA FLATOW: Aaron Bernstein, you agree?

AARON BERNSTEIN: Absolutely. And I think it’s critical to underscore that El Ninos have been happening as long as probably humans have been around and certainly longer And what’s changing is the climate around us. And so we know that there will be surprises during El Ninos, but we’re making the health of people potentially at greater risk as climate change unfolds. Because, as was mentioned, whenever an El Nino happens, it’s happening in the context of the existing climate.

And I think it’s just crucial to underscore that if we do what’s necessary to mitigate climate change, to address climate change, we’re likely to achieve the greatest public health victory in history. Bigger than vaccines, bigger than sanitation, bigger than antibiotics, because so much is at stake for people’s health, and El Nino just amplifies that risk. So I just think it’s crucial that we have– to understand we have this opportunity in our grasp, and I’m heartened to see the international community at the Paris conference acknowledge that we have to take action.

And as a pediatrician in particular, as someone who’s career has been dedicated to the welfare of children, I couldn’t be happier to see that. Because not only are children more vulnerable to the harms we’re talking about– the droughts, the floods, the famines– but they’re going to grow up in this world. And we really do owe it to them to do everything we can to ensure the healthiest possible future.

IRA FLATOW: All right. We’ll have to leave it that. Aaron Bernstein, Associate Director of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard. Madeleine Thomson, Senior Research Scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society in Palisades. She’s also the director of the World Health Organization and Collaborating Center on Climate Sensitive Diseases. Thank you both for taking time to be with us today.

MADELEINE THOMSON: [INAUDIBLE]

AARON BERNSTEIN: Thanks Ira.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Christopher Intagliata was Science Friday’s senior producer. He once served as a prop in an optical illusion and speaks passable Ira Flatowese.