Chasing Pluto, As Long As It Takes

23:19 minutes

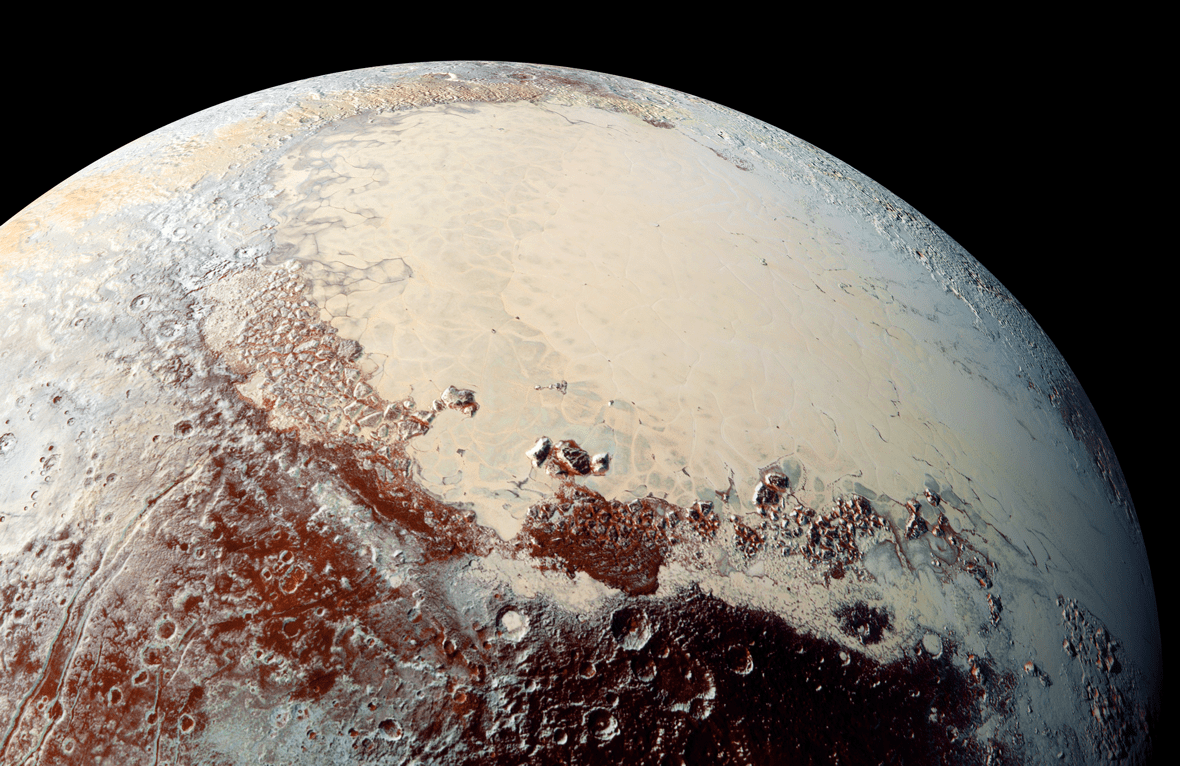

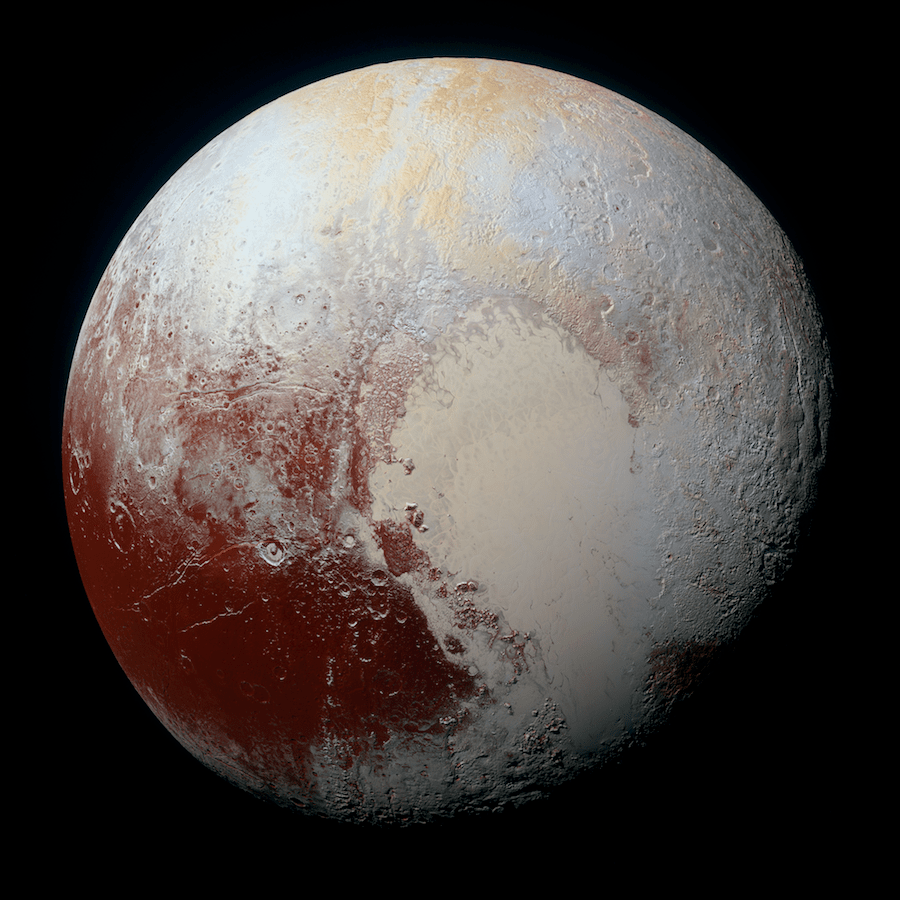

In July of 2015, the world was stunned to learn that Pluto, a tiny, distant dot that some didn’t even consider a planet, was a dynamic, complex, and beautiful world. It’s still geologically active, it has an atmosphere, and it may have an ocean buried under its icy surface.

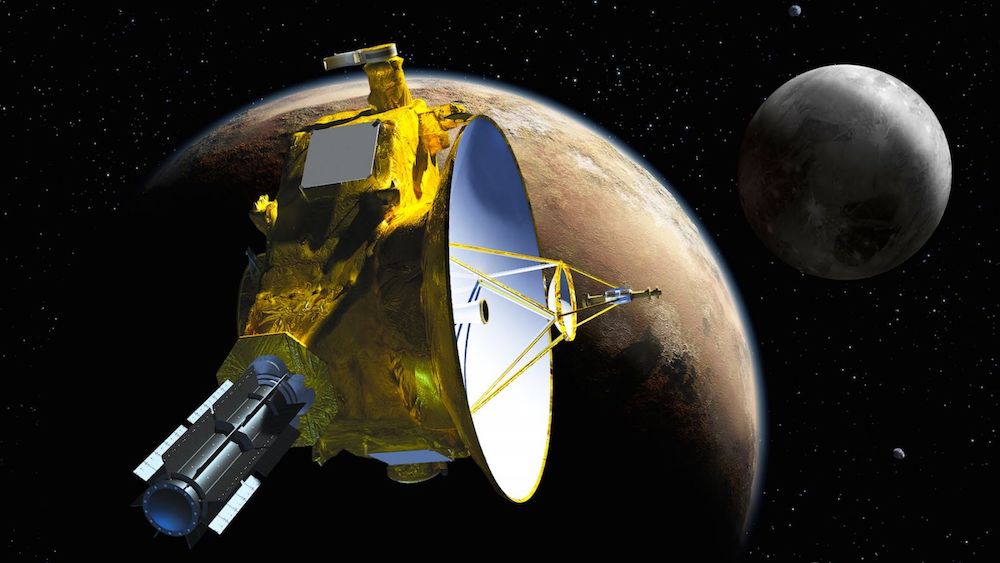

All of this is now known thanks to New Horizons, a probe that launched in 2006 to complete the tour of the solar system. But for scientists in pursuit of Pluto’s secrets since the late 1980s, it was a long wait. The mission faced political hurdles, budget battles, technical challenges, and near-disaster even as it was days away from speeding past Pluto.

[Read the excerpt for this book here.]

Alan Stern, the mission’s dogged principal investigator, and astrobiologist David Grinspoon have written a new book about the decades-long effort to visit Pluto. They join Ira to talk about the little space probe that could, and what’s left to explore in the far reaches of the solar system.

Alan Stern is Principal Investigator for NASA’s New Horizons mission, and a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute. He’s also co-author of Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto (Picador, 2018). He’s based in Boulder, Colorado.

David Grinspoon is an astrobiologist and a senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute in Washington, DC. He’s also co-author of Chasing New Horizons: Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto (Picador, 2018).

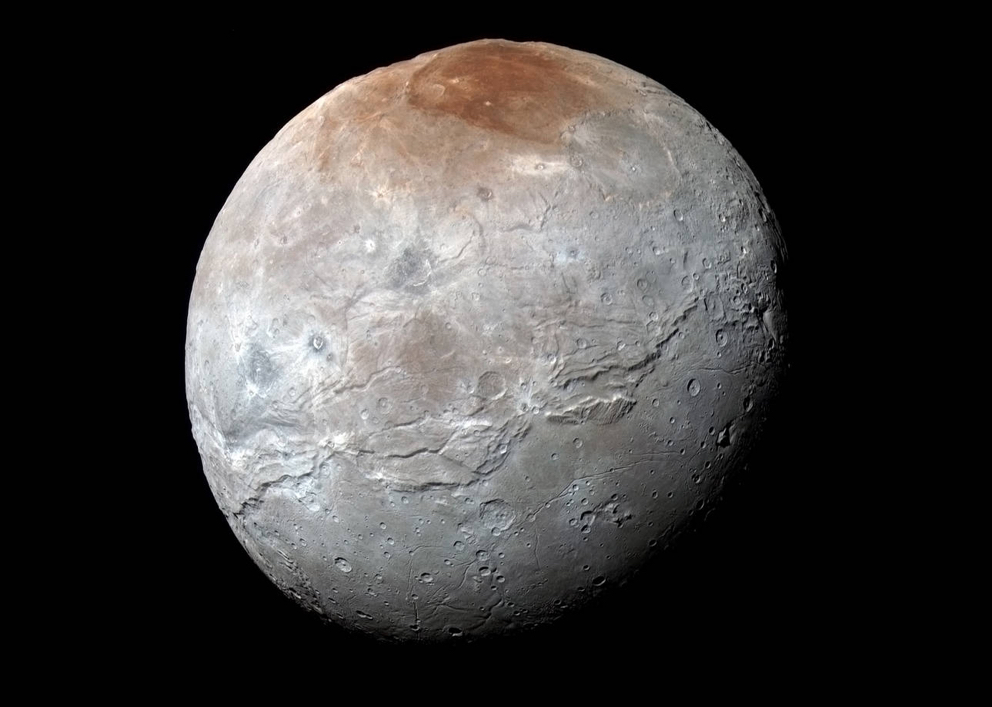

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Three years ago, NASA’s New Horizons probe finally sped past Pluto and its moon, Charon. We got stunning photos, surprising geology and chemistry, a possible subsurface ocean, and are still naming its many mountains.

Pluto, far from a dead chunk of rock, appears to indeed be an active, really interesting world. But it took a Pluto scientist decades of campaigning, near misses on budgets, and nail-biting technical challenges all to make it happen. The spacecraft even lost contact three days before flyby, and the team had to frantically re-upload huge amounts of crucial software before they finally got the data they so wanted.

How long have you been waiting?

ALAN STERN: [LAUGHS] Longer than I might care to admit.

IRA FLATOW: That’s principal investigator Alan Stern talking to us days before the New Horizons reached Pluto in 2015. He and astrobiologist David Grinspoon have a new book out with the story behind the dogged pursuit of the ninth planet. And you can read an excerpt on their website. Chasing New Horizons– Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto.

And Alan Stern and David Grinspoon are with me here in the studio. Good to see you. Good to see you in person. We talked to you over the phone or something. We never get to see you guys.

ALAN STERN: It’s great to be here, Ira.

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah, thanks a lot for having us on.

IRA FLATOW: The first question practically writes itself, per the title of your book. What made this mission to Pluto epic? What was so epic about it? It must be so surprising. I saw on the news that it was coming in.

ALAN STERN: I think there are several answers to that. First of all, it’s the epic farthest journey of exploration in the history of our species. Second, it was an epic challenge– and some would say battle– to get this funded. And it was an epic challenge as well to build a spacecraft in record time to make that Jupiter launch window and to do it for only 20% of the cost of Voyager.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. That is epic.

ALAN STERN: It was a lot of challenges.

IRA FLATOW: David, what would you say? Was what was the biggest–

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah. Well, to me, it’s also epic just for the role that it plays in our exploration history. We grew up with the Voyagers and the Pioneers and the Vikings and all that stuff. And so we saw the first exploration of a lot of the solar system– most of the planets. But there was this one planet that we had never been to.

So it sort of provides this capstone to what Carl Sagan used to call the initial reconnaissance of the solar system. So it’s epic in the way it fills out that historic journey from the stars just being dots to being places that we know.

IRA FLATOW: Reading this book, I almost lost count of how many times this project got cancelled. But in the end– you used the wording. And I found out you are not one to mince words in real life or in the book. You called the head of NASA ballsy when he went ahead and decided to finally launch. Right?

ALAN STERN: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah, that was a technical decision, not a funding decision. And I was referring to administrator Mike Griffin, who has a spine of steel.

IRA FLATOW: And what so difficult for him to make?

ALAN STERN: Well, the issue was that our launch vehicle got a clean bill of health, but a test version of one of the fuel tanks in the first stage which was being tested to its very limits burst at a lower pressure than the design had indicated it would. So there was some concern whether that might indict our fuel tank or other Atlas launch vehicles.

There was a careful examination of that by NASA engineers. And in the end, they came to a crucial meeting at NASA headquarters in which some of the administrators– key lieutenants, like the chief engineer of the agency and the head of Safety and Mission Assurance voted against launching New Horizons. Others voted for it and argued the case pretty strongly. I did as well.

It was a split decision. The administrator had to make the call. And Mike made the right decision. He authorized launch.

IRA FLATOW: Our number– 844-724-8255. 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us– @SciFri. You talk about the vote. Let me ask both of you about the vote to declassify Pluto as a planet, to make it a dwarf planet. And you spare no words in that. You said that there was a campaign to sort of vilify Clyde Tombaugh. Talk about that, would you?

ALAN STERN: Well, you know, Clyde Tombaugh did something utterly unbelievable in discovering Pluto. Remember, this search had been on by various observatories– some of the best people in the world at the time– for a quarter century. Here he came off the Kansas farm, hired to Lowell Observatory, and knocked it flat in one year. He discovered the planet they’d all been looking for 25 years.

He never had a false alarm. He simply was a sharpshooter and he found it. And in doing so, he was really two generations ahead of his time.

He discovered the Kuiper belt. And no one else could, until the ’90s, see other objects out there. And what the IAU did was essentially to start the erasure of his legacy. And I think it’s more than unfortunate. I will mince my words and stop there.

But I’ll say that it’s been made even worse by those who think there may be another large planet out there. And I suspect there are more planets out there. But I think that it is, again, another incredibly insensitive step in erasing Clyde’s legacy to call that Planet Nine.

IRA FLATOW: David, does it matter?

DAVID GRINSPOON: Well, there’s a level on which it matters, because it’s obnoxious, and it’s confused a lot of people. In the long run, it doesn’t matter. It’s not the most important thing. What’s important is the nature of Pluto and the fact that we’ve learned so much and explored it.

But it was a mistake– and that’s becoming more and more clear– the way that they attempted to redefine planet. It’s just not logical. They defined a planet in a way that ignores the properties of a body and just describes it in terms of what’s orbiting around it.

So it leads to these absurd contradictions. The Earth is not a planet according to that definition, if you move it out to the asteroid belt. And they also said that planets around other stars aren’t planets– the exoplanets. They said a planet orbits the sun.

So it was sloppy. They didn’t do it right. So people in our field– planetary science– kind of ignore that. And we refer to Pluto as a planet, just because that’s what it is.

And so in that sense, it doesn’t matter. But I think, ultimately, that definition will kind of be ignored and ultimately, they’ll probably fix it.

IRA FLATOW: Alan, originally, what made Pluto such an obsession to explore– this tiny little dot out there?

ALAN STERN: Well, it was a combination of things. First of all, we had found all these fascinating attributes. Pluto’s a binary planet. We’d never seen anything like that.

IRA FLATOW: Meaning it has another–

ALAN STERN: It has a moon that’s half its own size. And the balance point, like in binary stars, is between the two bodies. That’s a science fiction planet. We don’t have anything like that in our solar system.

It is in a very unusual orbit that is indicative, in fact, of being in the Kuiper belt– its location. It has an atmosphere and a very complex surface composition. And these things all conspired to be scientifically seductive to many planetary scientists.

But also, there was the beck and call of exploration. There was unfinished business. We had explored all the planets from Mercury to Neptune– not Pluto.

And what really made the difference was the discovery of the Kuiper belt. Because then, the National Academy of Sciences ranked this mission at the top. Because we realized there was a whole new class of planets– the dwarf planets– that deserved exploration, as had the giant planets and the terrestrial planets.

IRA FLATOW: So why was it so hard then to get the mission okayed?

ALAN STERN: Well, read the book.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: It’s a great book.

ALAN STERN: Right? When we started, we didn’t think it would be so hard. And a number of things happened. First of all, senior people in the field at the time, in the ’90s, they said, we should be doing more Mars missions. It’s closer. Why would we fly something out there that takes 10 or 15 years.

I had a very senior scientist say to me after I made a presentation, 2015? Everyone will be dead by then.

And then we had other twists and turns. David writes it very well. One time, we were on the verge of getting a new start from the agency and Congress, and a Mars mission blew up just before arriving at Mars.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, I remember that.

ALAN STERN: And the money was taken to replace that. And we were set back to square one. This kind of thing happened again and again.

IRA FLATOW: David, describe how hard it is to get something okayed through–

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah, well, it’s always a challenge. I mean, one reason I like this story is because people know that we’ve explored the planets and they’re excited about that. But they really don’t know the backstory of what it takes, long before you get to the launchpad– the challenges you have. And there are all these hurdles.

You have to get your community of scientists behind it so they rank it high enough. It’s competing with all these other missions. And then, of course, you have to get Congress to fund it.

But for this mission in particular, because it took so long, the rules kept changing. And the players kept changing– the people that had to approve it. So finally, they get what’s called a new start, which is, Congress has allocated the money, and it looks like it’s going to happen. And then we get a new presidential administration– the Bush administration. And they say, no, we’re changing our priorities. And they cancel it.

So you’re not even dealing with the same powers-that-be. They keep shifting and you have to start over.

IRA FLATOW: That explains why, today, we see so many different administrations coming and going and different directions to NASA and planetary exploration.

ALAN STERN: I think we’re in a better place now, actually. With the decadal survey process that was invented in the early 2000s, it’s become much more orderly.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Our number– 844-724-8255. They can also tweet us– @SciFri. OK, let’s go back to the mission then. July, 2015, we made it, and we got beautiful pictures, a year’s worth of data. Pluto became this really living, breathing world for a lot of us– active geology. That heart-shaped spot– we all saw it. Now you can’t get out of your mind.

Do you have any favorite finding? What’s your favorite? I’m sure you’ve been asked this question.

ALAN STERN: Sure. And I have lots of favorites.

IRA FLATOW: It’s like your children, right?

ALAN STERN: It’s like your children, you know? But unlike my children, I can talk about my favorites.

IRA FLATOW: OK. [LAUGHS]

ALAN STERN: And the one that I really like to point out are the discoveries about liquids. We have strong evidence that there’s a global ocean under Pluto’s surface, like Europa.

IRA FLATOW: A water–

ALAN STERN: A water ice ocean. Thank you. A water ice ocean like Europa or Enceladus. And we see places on the surface that look like liquids flowed, or, at least, slurries flowed. We see evidence for a liquid layer under that big heart-shaped region, which is the giant glacier called Sputnik, made of nitrogen. And there’s even a place with a 20-mile long apparent frozen lake and a mountain valley. It’s amazing.

IRA FLATOW: My jaws un-dropping now. How could that exist so far away in a liquid state, all the way out there?

ALAN STERN: Well, the dominant volatile material on the surface is nitrogen. And the current conditions on Pluto’s surface are below the triple point, meaning that pressure and temperatures are too low to allow liquids to stand on the surface or to flow on the surface.

So these are clues. It’s like an episode of CSI or something. Apparently, Pluto had a thicker atmosphere and warmer surface conditions with higher pressures at least once, but, we actually think, cyclically, in the past, due to polar tilt shifts called obliquity cycles or a Milankovitch cycles.

IRA FLATOW: And David, as an astrobiologist, I know you’re nodding your head up and down, like, yeah, maybe there’s life in those oceans.

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah, well, as an astrobiologist, I’m totally thrilled by the results of new horizons, first of all, just for the way that it illuminates this whole new type of planet. And once again, it surprises us and busts our paradigms about the range of types of planets that are out there and the range of types of environments that are out there.

But specifically, it looks as though Pluto probably does have a liquid water ocean underneath its surface. And as far as we understand the conditions for life, what do you need? You need water. You need organic molecules. You need energy.

Pluto probably has all of them. And so it has to now be added to the list of places in the solar system where there could be life. And that’s pretty exciting.

ALAN STERN: And where we should do a real search for that. And that calls for going back with an orbiter.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. In case you just joined us, we’re talking to Alan Stern and David Grinspoon, authors of Chasing New Horizons– Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto. And I have to say, I read a lot of science books– the writing in this is just wonderful.

ALAN STERN: Thank you.

DAVID GRINSPOON: Well, thanks a lot.

IRA FLATOW: And I know, David, you’ve done a lot of writing. So it shows.

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah, well, Alan’s a really good writer too. And this was a real collaboration. I wrote a lot of the first drafts, but that was after conversations with Alan where he opened up his brain to me. And there’s a lot of good stuff in there– a lot of memories.

But then we really workshopped the chapters and rewrote each other’s stuff a lot. And so it’s the result of both of our minds applied to this.

IRA FLATOW: OK. I agree. Let’s go to the phones. Gary in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Hi, Gary.

GARY (ON PHONE): Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

GARY (ON PHONE): Yeah, I’ve always wanted to know how it is that we fly these very fragile spacecraft through the asteroid belt.

ALAN STERN: Well, that’s a good question. And by the way, go Packers.

[LAUGHTER]

But the asteroid belt– when you see a textbook or a magazine article, it usually looks like it’s some sort of shooting gallery.

DAVID GRINSPOON: Or a Star Wars movie where they have to go through the asteroid field.

ALAN STERN: Exactly. Exactly. But it’s actually a very empty place. And the odds of getting hit are very low. The main thing that is out there that poses a danger are small micrometeoroid particles, the size of grains of sand or maybe pellets of rice.

And you may not know this, but NASA spacecraft that cross the asteroid belt, like New Horizons, actually wear a Kevlar shield– a bulletproof shield made of the same stuff as a SWAT team’s bulletproof shield– Kevlar.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you say one of the biggest dangers that you face– the unknowns– was, actually, maybe there are hidden moons of Pluto that you don’t know about, and debris around there.

ALAN STERN: In our case, it was, we started to find more and more moons of Pluto using the Hubble. While we were on approach, we were worried that, if there were unseen moons, they could generate rings, and that flying through that kind of debris really could be too much for the Kevlar shield and could take the spacecraft out.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. We have lots of tweets coming in. Mark says, what do you hope to find with New Horizons’s flyby of the Kuiper belt?

ALAN STERN: Well, on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day this coming year, New Horizons is going to conduct another flyby a billion miles beyond Pluto. It’s unimaginable, almost. But we’ve been traveling fast for another three years, and we are going to one of these building blocks Kuiper belt objects– building blocks of small planets like Pluto.

Nothing like this has ever been explored before. We really don’t know much about it. We don’t know what to expect, except, it’s ancient. It’s been cold and kept in the deep freeze since formation.

IRA FLATOW: What is it?

ALAN STERN: We’re going exploring.

IRA FLATOW: What is the Kuiper belt?

ALAN STERN: The Kuiper belt is the third zone of the solar system. It’s a disk or a belt beyond the orbit of Neptune of comets, planetesimals out of which planets were formed and dwarf planets, that is kind of the solar system’s attic, if you will– leftover bits and planets from the formation days of the solar system.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. So there could be lots of things in there.

ALAN STERN: Yeah. So Pluto is about 400 kilometers in diameter. The target that we’re going to, which has been nicknamed Ultima Thule, a Norse phrase that means “beyond the farthest frontier,” is about 25 kilometers across– 1% the diameter of Pluto.

But it may have moons. There’s some evidence for that. It may be a binary itself. And it probably holds clues to the formation of the solar system. We’re going to fly much closer than we flew to Pluto and have, I think, even more spectacular imaging.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, can’t wait. Well, we’re going to take a break. And come back. We’ll talk lots more with the Alan Stern and David Grinspoon, authors of Chasing New Horizons– Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto. And after the break, we’re going to talk a little bit more about, should we go back to Pluto, the case for an orbiter to probe the planet’s moons, hunts for an ocean, and more.

Why Pluto instead of maybe the moons of Jupiter? Lots of oceany stuff that we’re going to talk about after the break. Stay with us.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking this hour about Pluto with the authors of Chasing New Horizons– Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto, Alan Stern and David Grinspoon.

And as we were going to the break, we were playing some music that you guys would recognize. David, you want to tell us about that?

DAVID GRINSPOON: Yeah, and I also have to mention that that intro music you just used– I’m your Venus– thank you for that. But yeah, the outro music that you played right before the break was a song called “Faith of the Heart.” It’s actually the theme song for one of the Star Trek series.

And that song has a role in the New Horizons mission. And we talk about it in our book, Chasing New Horizons. Because when the team was waking up New Horizons from hibernation– and hibernation is an interesting part of the story, because it was an innovation of this mission. Since you’re going nine years, you find a way to put the spacecraft to sleep and then wake it up. It helps in a lot of ways.

But when they were waking it up, they decided they need a wake-up song, just like the astronauts. It is tradition that they have a wake-up song. So they chose this song “Faith of the Heart.”

And they chose it because it’s got a space association with Star Trek. But also, it’s a story of kind of an epic journey and succeeding against all odds. But it also talks about, I’ve got faith, the faith of the heart.

And the funny thing is, when they picked that song, they had no idea that, when we finally got to Pluto much later– what’s the first thing you see and what’s the first thing you think of when you see Pluto? A big white heart. So it turned out to be so much more appropriate than even they could have imagined when they picked the song for New Horizons.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great. In the few minutes we have, let’s talk about the future. Let’s talk about the idea of sending a probe around–

ALAN STERN: An orbiter.

IRA FLATOW: –an orbiter around the planet. What would it do? I’m going to give you a blank check now.

ALAN STERN: Definitely.

IRA FLATOW: I know you’ll never get another one.

ALAN STERN: Right. It’s going to be the equivalent of Galileo or Cassini for the Pluto system. It’s going to explore the surface and atmosphere of Pluto. It’s going to dip down in the atmosphere and actually sample it with mass spectrometers and other devices. It’s going to be have very sensitive radio tracking to find that ocean, how deep it is, under how much ice.

It’s going to bring radars so we can look through the glacier to find its depth. It’s going to map every part of Pluto. New Horizons only mapped about 40% as we flew by one hemisphere. It’s going to make close flybys of all five moons. And it’s going to do more.

IRA FLATOW: But it doesn’t exist, even on paper, yet.

ALAN STERN: Studies are taking place, right now, as we speak, in several places, for how to do this mission.

IRA FLATOW: And David, what would be your dream instrument, as an astrobiologist, to have on there?

DAVID GRINSPOON: Well, the first thing I want to do with an orbiter is see the other side of Pluto. With a flyby, you have to pick one hemisphere to fly by. And one of the innovations on New Horizons was there was this great telescope– this instrument called a LORRI– where you could see what is now the lesser known side of Pluto from a distance. So we have some idea of what it’s like.

But to map the entire surface now that we know what an enticing place it is– but as an astrobiologist, of course, I really do want to know what’s underneath and if there is an ocean. So I think gravity monitoring of the spacecraft, which you do just by monitoring its orbit with Doppler very carefully– and who knows? Since you’re giving me a blank check, maybe some kind of magnetic sensing of the interior of the planet and seeing what’s underneath that ice.

We don’t usually get offered a blank check. So we’re going to now have to kind of redesign this mission.

IRA FLATOW: And it’s just as fictional as the one in my back pocket. Let me see if I can get a last question before we go. Victor in San Francisco. Hi, Victor. Victor, are there? Oh, let me try and push the button again. Hi, Victor.

VICTOR: Hi.

IRA FLATOW: Hi. Go ahead.

VICTOR: Just a quick one– how are they able to get such high resolution images and videos from so far away?

IRA FLATOW: Alan?

ALAN STERN: Yeah, well, it’s because we’re not so far away. We actually go close to Pluto and its moons. And we have more than just telephoto lenses. The LORRI instrument that David was just talking about has its own telescope, about the equivalent of a very high tech Celestron 8 or Meade 8, that gives us this tremendous resolution.

IRA FLATOW: Could it eventually go out as far as Voyager? Is that still its function?

ALAN STERN: Oh, absolutely. The spacecraft is escaping the solar system. So it’s going to go that far. It’s got enough power in the nuclear battery to operate another 20 years.

And we have plenty of fuel on board. We may even be able to find another fly by target after Ultima Thule. But at the very least, it could do a Voyager-like mission when it finishes exploring the Kuiper belt.

IRA FLATOW: And are you actually mapping that out, where we could go?

ALAN STERN: We are. In fact, very few people know– I’ll say it on your show– that, although we’re making a close flyby Ultima Thule, we’ve studied already about a dozen other Kuiper belt objects with that telescope, LORRI, and we’ll be studying at least two dozen more this year, next year, and in 2020.

IRA FLATOW: Is it possible to find something as magnificent as Pluto out there, do you think?

ALAN STERN: There may be. But we’re not going to go close enough to get those kind of surface details.

IRA FLATOW: David, I’m giving you last word, because you’re sitting here like a dog looking at a bone.

DAVID GRINSPOON: You’re talking about what’s going to happen next and in the future and, ultimately, to New Horizons. And I think it’s worth pointing out that, no matter what, New Horizons is now on a trajectory that it will inevitably leave our solar system, leave the sun’s gravitational influence, and it will become the fifth artifact of our civilization to forever wander the galaxy and outlive our civilization, even outlive our planet.

So Alan and his team created something that not only was a wonderful mission of exploration in our time, but something that, like only other four human artifacts so far, will truly live forever.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great. And it’s a great book– Chasing New Horizons– Inside the Epic First Mission to Pluto with Alan Stern and David Grinspoon. Thank you both for dropping by today.

Copyright © 2018 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.