How The Humble Asiatic Dayflower Revealed Clues To Blue Hues

This briefly-blooming plant gave Japanese artists a distinctive dye—and helped scientists answer a color chemistry mystery.

A woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai, from the Edo Period, about 1800-05, titled 'Express Delivery Boats Rowing through Waves (Oshiokuri hatô tsûsen no zu),' from an untitled series of landscapes in Western style. Conservation scientists analyzed the print with fiber optic reflectance spectroscopy, which identified the blue-gray color at the top of the tallest wave as dayflower blue. It also has traces of indigo, iron oxide red, turmeric, and copper. Credit: William S. and John T. Spaulding Collection/© Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/Used with Permission

As summer winds through fall, a tiny, delicate flower wakes from its slumber. Its petals pop periwinkle-blue along the edges of fences and flowerpots—but its vibrant complexion is only temporary. Fittingly nicknamed the Asiatic dayflower, each bud blooms at dawn, only to wilt away by midday. While this low-lying plant is seen as a noxious weed in Europe and North America, in its native regions in Asia, artists and scientists have harnessed its ephemeral color for centuries.

As early as the 11th century, Japanese illustrators and printers created a blue dye from the petals of the dayflower, also known as tsuyukusa, or “dewflower,” in Japanese. Various plants and minerals have long been the basis of all kinds of dye colors: Beginning in the 1760s, intricate Japanese woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e, for instance, depended on safflower for fiery reds and turmeric for bright yellows, and the dayflower for a powdery blue. When the traditional dayflower dye is fresh or well preserved, “it appears as a purplish-to-slate-blue in color,” says Michiko Adachi, an assistant conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which holds a collection of over 50,000 Japanese woodblock prints and illustrated books. The dye was used to stain kimonos with pale-blue sketches to make patterns, a technique known as yūzen-dying, or to wash a woodblock print with blue streaks, like in the raging seascape woodblock print pictured above. The fading sweep of steel blue beneath the white-capped peak of the mighty wave is the result of dainty dayflower petals plucked hundreds of years ago.

This unassuming bloom is one of just a few blue-colored flowers, including the Himalayan blue poppy, hydrangea, muscari, and the Chinese bellflower. While shades of bold blue surround us today, the color blue is uncommon in nature. Species of blue flowers in nature account for less than 10% of all flowers. The rarity of blue has long intrigued scientists, leading to quests to genetically modify the truest blue buds, to identify natural and healthier dyes in foods, and to unravel the chemistry behind the color.

At its most basic, a flower’s color is determined by various types of pigments: chlorophyll results in green, carotene reflects orange, yellow, and red, and anthocyanin gives reds, purples, and blues. But it quickly gets more complex, explains Kumi Yoshida, a professor at Nagoya University in Japan, who began her research on blue flower coloration with the Asiatic dayflower. A red rose and a blue coneflower both contain anthocyanins, yet their petal colors appear very different. Since the 1900s, scientists have pondered this chemistry mystery. As Yoshida puts it, “[How] can the same pigment develop red and blue flowers?”

Most anthocyanins naturally absorb blue light, causing the human eye to see the flower as red—only when anthocyanins’ structure is arranged with specific chemical groups will we see petals as blue. “Many factors [have to] combine to develop the color blue, which is why I think blue color is so rare in nature,” Yoshida explains. Various chemical components and environmental factors—such as a higher pH level within flower petal vacuoles, where pigments are stored—contribute to the various shades of blue that we see in flowers.

Another one of the key clues to what makes flowers blue was discovered within the small petals of the Asiatic dayflower. In 1958, Kôzô Hayashi of the Botanical Institute, Tokyo University of Education and a group of researchers followed a hunch: Back in 1919, two Japanese brothers, a botanist and a chemist, developed a theory that certain metals combined with anthocyanin in the dayflower’s petals, resulting in its blue color. (At the time, the theory was ignored by European researchers, Yoshida explains.)

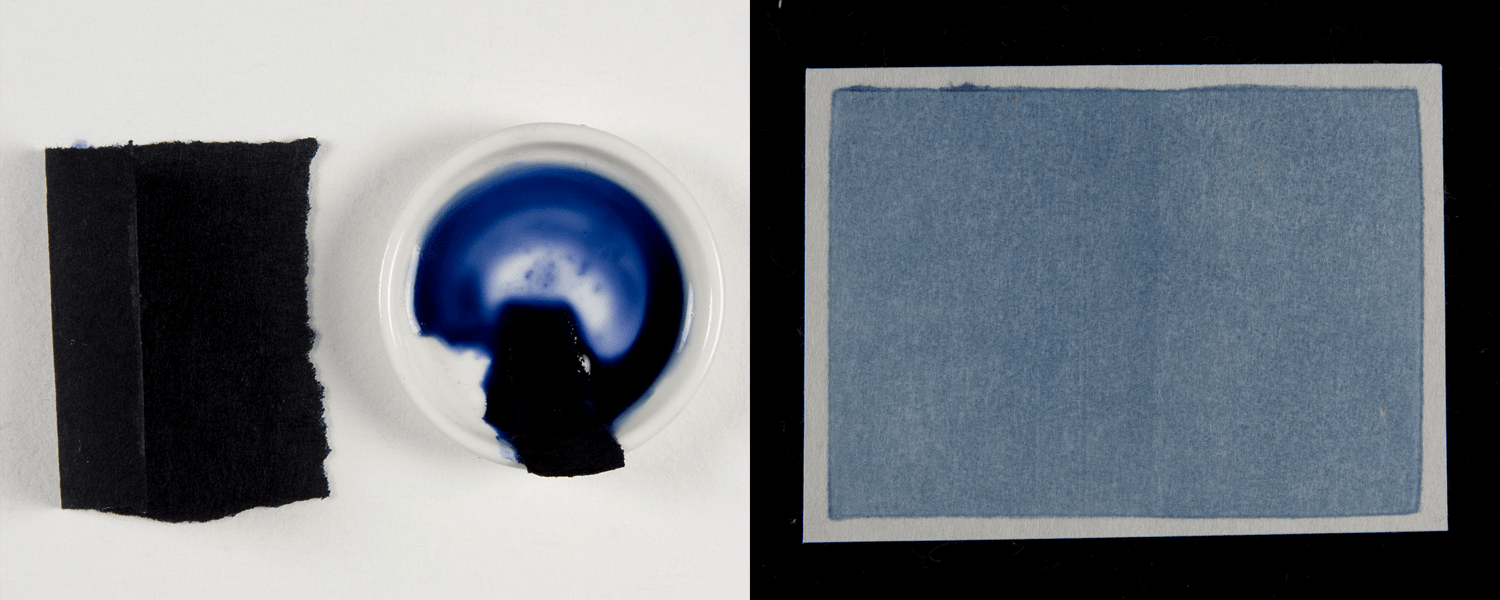

So taking the dainty petals, Hayashi’s team isolated and crystallized its pigment, which they named commelinin after the flower’s Latin name, Commelina communis. Analyzing the brilliant-blue commelinin, the researchers took a closer look at its structure: They found that its anthocyanin molecules and magnesium ions created a self-assembled, supramolecular metal complex called a metalloanthocyanin—one of the fundamental mechanisms that scientists now know results in blue coloration, Yoshida says. More recently, Yoshida and fellow researchers have found that different types of metal ions are also a key to different pigments in other blue flowers, such as aluminum ions in hydrangea, and ferric ions in the Himalayan blue poppy.

Metalloanthocyanins are a “really complicated structure, but it’s essential,” Yoshida says, adding that the Asiatic dayflower’s “color is unique.” Commelinin is the pigment behind the prominent blue that Edo Period Japanese printers and artists used on woodblocks, as well as in yūzen-dying kimonos and textiles, Yoshida documents in a history of blue flower research.

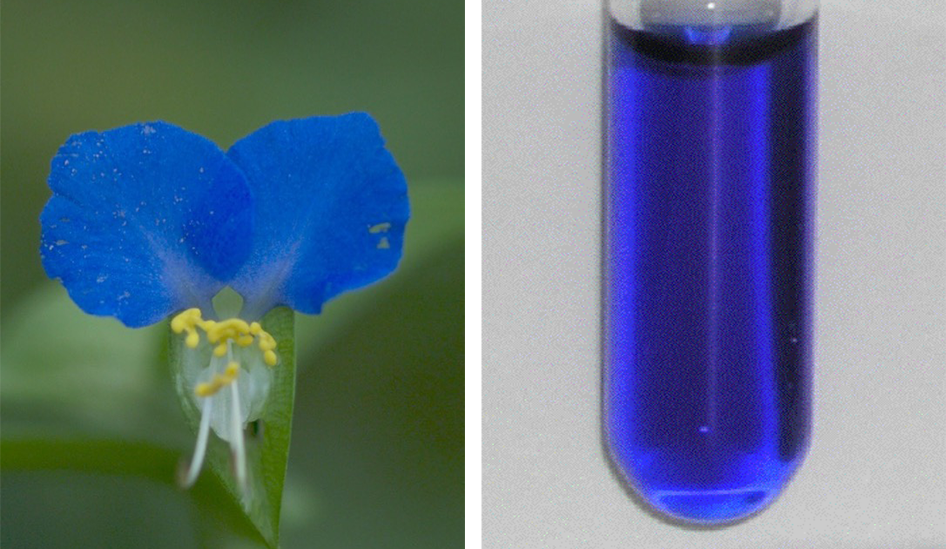

(Left) Dayflower paper (青花紙 aobanagami) and the dye extracted from the paper with water. (Right) Dayflower dye printed on hōsho paper by Asian Conservation Studio, MFA, Boston. Learn more about how dayflower paper is traditionally made. Credit: Joan Wright/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Farmers in what is today’s Shiga prefecture, grew and picked the dayflower in batches during the summer months in order to create blue dye. “Since the flower only lasts until midday, the petals have to be picked in the early summer morning, and picked every day, so it was hard labor,” says Adachi. After tediously sieving and squeezing the petals, the fresh blue liquid was brushed onto a special Japanese paper, called aobanagami or aigami, and saturated up to four times its weight. “This process needs to be done in a day, as the extracted dye does not last,” says Adachi. “It will start to turn brown.” The dried paper was a vessel, like a kind of inkwell, for artists and painters. Since it’s water soluble, they would later add water to the paper to re-liquify the dye.

But its solubility to water makes the final color susceptible to moisture. Depending on the artwork’s preservation, exposure to humidity can shift from purple and slate-blue tones into a greenish sickly yellow over time, Adachi explains. But Japanese artists and painters were known to mix and experiment with the colors. Some art historians say that through careful observation of how the dye could change, artists sometimes intentionally exposed the dyes to the elements to create unique tones and colors.

Asiatic dayflower, Commelina communis, blooming nearby a rice field. Credit: Shutterstock

Around 1820, the subtle blue of the dayflower dye started to become overshadowed by the bold shades of Prussian blue, the first synthetically made pigment which was more stable. When Adachi visited Japan between 2017 and 2018, there were only three farmers left who were growing and producing the dayflower paper with traditional practices. A local museum in Kusatsu tries to preserve this knowledge by holding summer programs with one of the farmers, where participants can learn about the process. Despite its nearly obsolescent use today, Asiatic dayflower dye lives on as a defining characteristic of historic Japanese prints and artworks, she says.

“I’d like to believe that the artists and printers liked the translucent and delicate quality of the dayflower’s colors,” says Adachi, who notices the flowers when she passes by the buds’ brief blossoms along fences where she currently lives in Boston.

The fading color is perhaps emblematic of the petals which it came from—the fleeting, fickle dayflower immortalized in the 11th-century Japanese folklore classic, The Tale of Genji:

“It was true then: he had after all the shifting hue of the dewflower [sic]. She had heard about that. She had heard, albeit in general terms, that men were good at lying, that many a sweet word went into the pretense of love.”

Special thanks to Joan Wright, conservator and recent retiree of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Naonobu Noda, principal scientist at the Institute of Vegetable and Floriculture Science at the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization in Japan.

Lauren J. Young was Science Friday’s digital producer. When she’s not shelving books as a library assistant, she’s adding to her impressive Pez dispenser collection.