Why Beech Leaf Disease Is Easy To Spot But Tough To Treat

In just a decade, this unusual disease has spread from Ohio across the Northeast. Scientists are testing treatments, but answers come slowly.

Backlit leaves of an American beech tree show dark bands, a symptom of beech leaf disease. Credit: Heather Faubert

Beech trees from Ohio to New England are losing leaves and dying off in alarming numbers. The American beech, recognizable by its smooth gray trunk, is a key species in many eastern forests and provides nutritious beechnuts favored by animals from woodpeckers to deer to black bears. But now a microscopic worm called a nematode is threatening the trees on a growing scale. As far as plant parasites go, nematodes are common, but they tend to damage the roots. The species of nematode that is causing Beech Leaf Disease (BLD) is different: It afflicts the leaves, and it’s deadly.

“There’s never been a foliar nematode that can cause mortality of a large forest tree like beech,” says Dr. Nicholas Brazee, a plant pathologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst’s Extension Plant Diagnostics Laboratory. Because there’s no precedent for this kind of pest, there were no obvious treatments to consider when the disease emerged. “Researchers are just kind of starting from ground zero to see what will possibly work,” he says.

The telltale signs of beech leaf disease—and the challenges of treating it—can be traced back to the nematode’s cycle of movement. They occupy the leaves themselves during spring and summer, reproducing all the while, and then migrate into new leaf buds from late summer into fall. The nematodes overwinter inside the buds, feeding on developing leaves and laying eggs. In spring, both eggs and nematodes in all stages of life can emerge along with the young leaves when the buds open.

Beech leaf disease affects the American beech (Fagus grandifolia), a tree found in forests across the Eastern United States and parts of Canada, as well as European and Oriental beech that are grown ornamentally.

“This has got to be one of the easiest diseases to make an identification,” says Dr. Richard Cowles, an agricultural scientist at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.

It shows up in about the same way across beech species: Looking up at a leaf, the light shining through reveals dark bands between veins extending out from the central vein. Looking down at the top of the leaf, the bands may not be visible until fall, when they can appear yellowish.

The banding symptom of BLD is caused by nematodes inside the original leaf bud. There, the nematodes interfere with the leaves’ development, causing cells to grow larger and in thicker layers. When leaves emerge from the buds in spring, they already have the unmistakable bands. In the course of the growing season, affected leaves can distort, brown, and thicken. The dark bands can also be raised, bending the surface of the leaf into a convex cupping shape. Affected leaves eventually fall off the tree earlier than a healthy leaf would.

As the disease progresses year after year, buds may become so infested with nematodes that they consume all the leaf tissue in the bud, preventing the leaves from emerging at all. Without new leaves to photosynthesize, branches die.

“First little twigs and then entire branches and then probably the whole tree would die because they don’t have any functioning leaves anymore,” Cowles says.

This progression of infection and die-off tends to happen from the bottom of the tree upward. Cowles says this is because rain washes nematodes down the tree, where they accumulate on the lower branches. The ease with which nematodes are transported by water may also explain why BLD appears to progress more quickly in trees in New England than in trees in Ohio.

“We have a more humid climate here [than in Ohio] and we have rain events that are very conducive to the successful migration of the nematodes from the leaves to the buds,” Cowles says.

But it’s probably not just water transporting the nematodes. Scientists believe they may be carried by birds and insects as well as the many animals that feed on beechnuts—which emerge late in the growing season when nematode populations are at their highest, Cowles says.

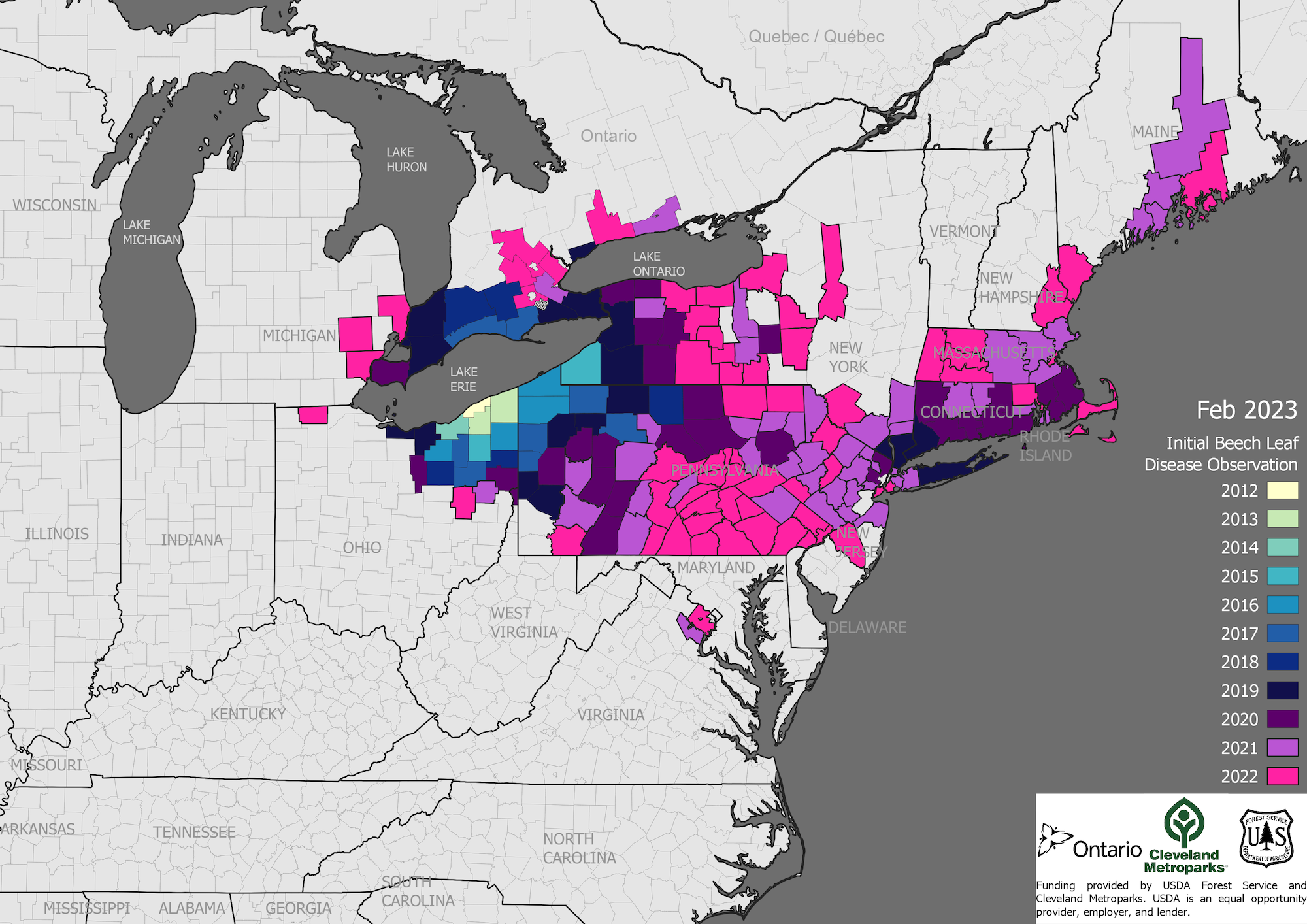

After beech leaf disease appeared in northeastern Ohio in 2012, it radiated out to the surrounding region and Ontario, Canada, Brazee says. Then in 2019, it jumped east, showing up in southwestern Connecticut and neighboring Long Island, and spread quickly from there. It’s now in at least a dozen states, with Vermont reporting its first case this month.

Because beech trees grow together in stands and the disease is spreading so quickly, neither Cowles nor Brazee thinks it can be stopped.

“The forest situation is fairly hopeless,” Cowles says. But Brazee points out that it will eventually slow. We’re in an early “killing front” phase of the epidemic, with the nematode sweeping through in huge numbers, he says.

“At some point when there is this big die-off of beech, the nematode population will decline and it’ll probably be much easier to manage it,” he says. “But we have no idea how long that’ll take.”

The outlook may not be as bleak for ornamental trees. Part of what makes BLD so tough to beat is constant reinfection from surrounding trees. But for individuals isolated from other beeches, as those in gardens or landscaped areas might be, it may be easier to keep nematode populations in check, Cowles says.

Researchers are studying several different approaches to treatment, and while some chemicals show promise, the specifics of application—how much, how often, what time of year—are still unclear. It can take years to understand the effects of a treatment on a tree, and the disease hasn’t been around long enough for researchers to gather the data they need to fill in those gaps and make concrete recommendations. As a reminder, it’s best to speak with a licensed professional before purchasing or applying a pesticide.

One product that’s had positive results in early research is a fungicide and nematicide called fluopyram (sold commercially as Broadform) that can be applied as a leaf spray. There aren’t yet published findings on its use to treat BLD, and one particular challenge has been determining the timing of application. This is because there are nematodes at overlapping life stages on an infected tree, and the chemical won’t necessarily reach nematodes that are inside buds. It’s also unclear whether it affects their eggs. Cowles suggests applying fluopyram just once in the spring, after young leaves have fully expanded. At that time, he says, the population of nematodes would be at its lowest and the tender leaves would absorb the chemical well, allowing it to kill the nematodes inside them. Another approach is to apply it later in the growing season when nematodes are migrating from the leaves to the buds (but ideally before they enter the buds). Some arborists recommend multiple applications during the growing season, though Cowles points out that there could be some risk of the nematodes developing resistance to the chemical.

Another product, potassium phosphite, is known to boost plants’ own defenses, and early research by Cleveland Metroparks and Davey Tree Expert Company on 40 small trees (2-4 inches in diameter) over six years suggests that it can also protect against the effects of BLD. It can be applied a number of ways: soil wash, trunk injection, bark spray or leaf spray. Cowles says researchers have some insight into the mechanism at play based on how potassium phosphite works to protect wheat from a different nematode—it interferes with the nematodes’ ability to hijack the plant’s cell development. What’s still unclear is the best timing of application and ideal quantity to use for different sized trees, though Cowles and other scientists are conducting research on larger trees.

For homeowners looking to treat their infected trees, Brazee recommends contacting an arborist who has experience with BLD. Chemical regulations vary by state, he says, and chemical options may require a pesticide applicator’s license.

One last option: Simply keep trees as healthy as possible so they can try to resist the nematode on their own, Brazee says. This could mean creating a large mulch ring around the tree so that the roots aren’t competing with turfgrass or other plants; keeping the tree well watered; managing other pests and soil pH; and keeping the soil in optimal condition by providing it with organic matter and nutrients.

While he’s not optimistic that those measures alone will save most trees, Brazee says it’s something people are trying since it’s unclear how well the chemical options are working.

“We just need some more time to assess how the treated trees are faring on a year-to-year basis.”

Robin Kazmier is Senior Editor, Digital. She writes and edits articles and helps shape Science Friday’s digital strategy. Her favorite bird is the squirrel cuckoo.