Relearning The Star Stories Of Indigenous Peoples

How the lost constellations of Indigenous North Americans can connect culture, science, and inspire the next generation of scientists.

Credit: Christie Taylor

Listen to a conversation on Science Friday about the historical role of science in Indigenous communities and considering a broader definition of science.

“They’re coming out,” says Wilfred Buck. “They’re starting to come out.”

It’s a freezing cold night on the shore of Lake Winnipeg in rural Manitoba, Canada, and we are waiting for the stars. It’s early May, but I’m wearing three sweaters and huddled next to a crackling, popping campfire, listening to Buck tell us the stories behind constellations I’ve never heard of until tonight.

“Right below the grandmother spider is the Pleiades, the seven sisters,” says Buck. “And that’s called Pakone Kisik. The hole in the sky. And the hole in the sky is where we come from.”

Wilfred is Cree, also known as Ininew, one of Canada’s largest First Nations groups. He’s telling us stories he’s gathered from Indigenous communities across Manitoba—like how the Star Woman saw Earth from another dimension, fell through the hole in the sky, and became the first human on this planet.

“We come from the stars,” Buck says.

When most of us look at the night sky, we’re used to seeing stories not of Indigenous origin, but of Greek or Roman: Andromeda chained to a rock, Perseus staring down a sea monster, Hercules slaying a lion. But just as the people of early Western civilizations looked to the stars and told stories about them, so did Indigenous people around the world. In North American communities, the stars hold bears, sweat lodges, thunderbirds, and more.

Some of those stories are part of how Indigenous people made sense of the world around them—a form of science separate from, but with kinship to, the enterprise of observation, prediction, and questioning built around what we call the scientific method.

“We come from the stars.”

But how do you connect the two? That’s where Wilfred comes in. He’s a part of a growing effort to reintroduce Indigenous stories and traditions back to Cree and other Indigenous communities. This weekend is an example of that effort. Tipis and Telescopes, the name of the gathering, is a coming-together of far-flung Indigenous teachers, local youth community leaders, and, tonight, one science reporter from the United States.

It’s a weekend of stories, astronomy, and ceremony—including hours every afternoon in the sweat lodge. Wilfred is relaying star knowledge and teachings, but also tales of science. The tilt of the Earth, the precession of our axis, the northern lights, and the peculiar path Mars takes through the night sky.

“Because Earth orbits the sun faster than Mars, at certain times Earth passes Mars, [and] it looks like Mars does a circle in the sky,” Buck says. “Retrograde motion. So they call it ‘kitom pampaniw’—circles back. Another name is ‘mooswa acak’—moose spirit. Because when a moose is startled, it’ll run in a big, huge circle, and then continue on its way.”

Three days and 2,000 miles later, I’m in Ottawa, at the Canada Science and Technology Museum. It’s one of the premier science museums in the country. In their space exhibit, you can hear more star stories—alongside a hundred-year-old telescope, and displays about radio astronomy.

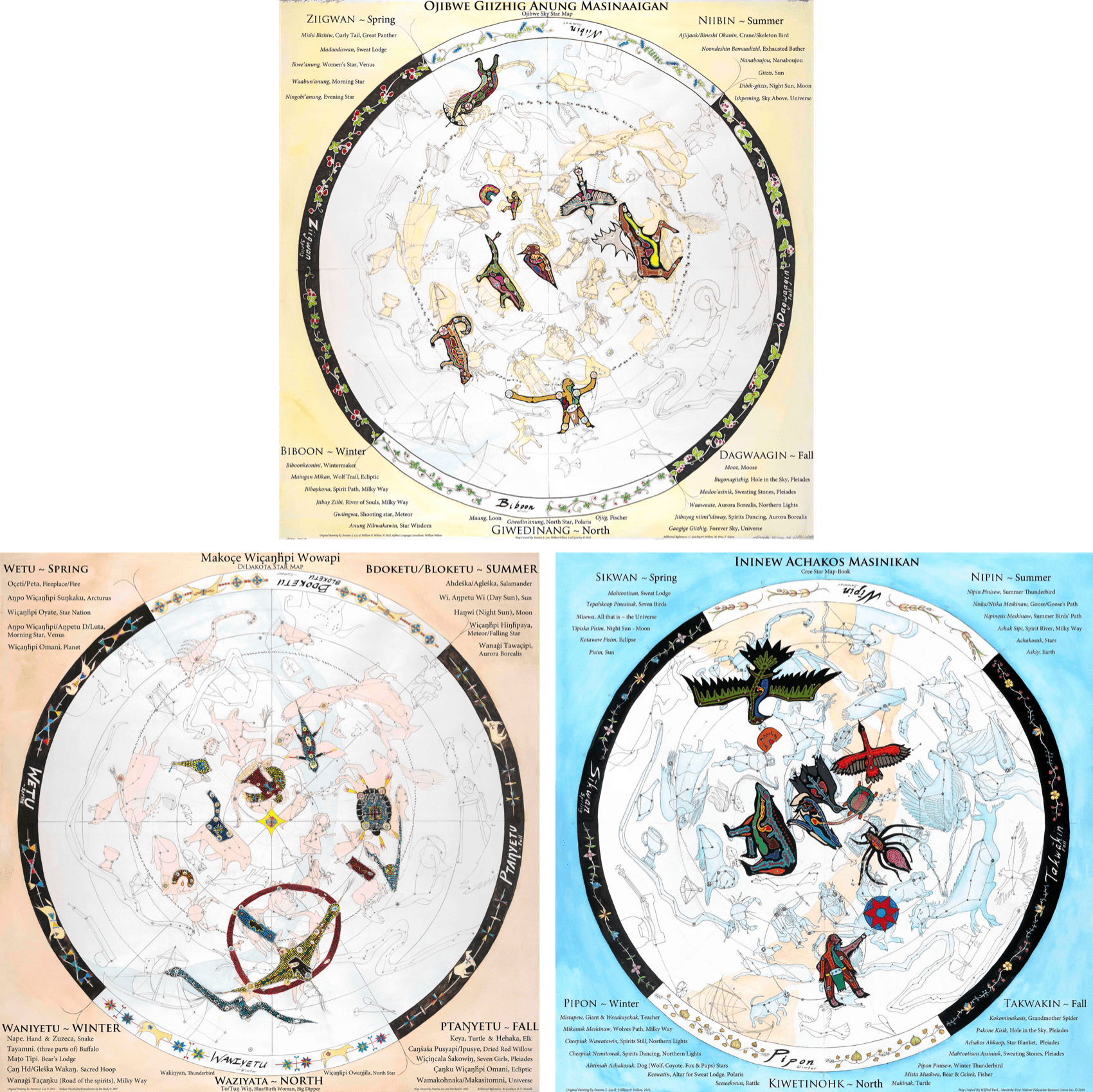

David Pantalony, curator of physical sciences at the museum, is showing me around. “We have here the wall called ‘One Sky, Many Astronomies,’” he says. “We have five different languages here. French, and then the Ojibway, then the Dakota/Lakota, and then the Cree languages.”

On the display are Greek and Roman constellations in muted colors, with the constellations of Canada’s Indigenous cultures painted, bright and beautiful, on top of them: loons, fishers, thunderbirds, the hole in the sky where we come from, and Mista Muskwa, the bear that sits atop the stars we know as the Big Dipper. Buck’s voice comes out of a headset, telling the story of that bear, a bully who was defeated by the seven brave birds that form the ring Westerners know as Corona Borealis.

(From top to bottom, left to right) star maps from Ojibway, Dakota/Lakota, and Ininew/Cree First Nations. Credit: Wilfred Buck © 2016, Annette S. Lee, William P. Wilson, Carl Gawboy, © 2012, Annette S. Lee & Jim Rock © 2012, and Annette Lee, William Wilson

Here’s a question Pantalony gets sometimes: What is a series of star stories doing in a museum dedicated to technology and science?

“People are surprised, but then it makes sense,” he says. “Of course cultures would have different stories based on this massive canopy from horizon to horizon that unfolds before our eyes every night.” Just like the telescope that sits in the museum, the story about Mars circling around in the sky like a startled moose is also an instrument of astronomical observation.

In 2008, Canada began a major effort to right the wrongs of colonization. The process, which aimed to recognize the rights of Indigenous groups and shape a new relationship of respect, was broadly referred to as truth and reconciliation. At the museum, this took the shape of a conscious effort to include Indigenous culture and technology in the story of Canadian science—from snowshoes to star stories.

The museum was so serious about getting the details right that they brought in Buck as a co-curator, along with Indigenous astronomer Annette Lee, who is both Dakota/Lakota and Ojibway.

“As much as there’s this idea that science is all rational, science is immune from culture, that’s simply not true. Science itself is not actually separate from culture,” she says. “It came from a specific culture, and that’s Western European.”

Lee means that our very picture of what science is was shaped by Western European history and the biases of that culture.

But science is something anyone can do, and, Lee says, everyone has done. The process on paper is simple: closely observe the world, test what you learn, and transmit it to future generations. That Indigenous cultures have done so without test tubes doesn’t make them unscientific, she says—just different.

On the day I visit the museum, a group of students from nearby Gloucester High School is there too. They’re all Indigenous, including Jessie Kavanaugh, who is Anishinaabe, from a First Nation called Animakee Wa Zhing in northwestern Ontario. “And I’m Bear Clan,” she says.

Jessie Kavanaugh. Credit: Christie Taylor

At the museum, they explore the constellations as newcomers, rotating the images of the sky to see the arrangement of stars on the day and time they were born. Animals roll in and out of the circular frame—a turtle, a spider, a thunderbird, and a marauding bear named Mista Muskwa.

But Kavanaugh tells me the stories she’s reading on the walls aren’t ones she ever learned growing up.

“I’m 18 and I’m learning this now and I still don’t know anything about it,” Kavanaugh says. “I feel like I know more about the Greek or Roman, their constellations, than I do my own.”

Wilfred says this is common in Indigenous communities. Adults and children alike have lost stories of the stars and other knowledge from collective memory. It’s direct fallout from the ways in which colonizing Europeans killed Indigenous people and weakened links to their culture. After more than 14 years of collecting star stories from Indigenous elders around Manitoba, Wilfred says he’s managed to gather only two dozen.

“If you have a village of a hundred people, and every person knows one word to a song that has a hundred words in it, everybody getting together can sing that song. That’s the whole accumulated knowledge base of their people,” Buck says. “And then one morning, you wake up, and 85 of them are gone. And you have to piece together what you remember, and what you have.”

The result is generations of people who are fighting to even know their own language. And young Indigenous people look up to the sky at night and see only the stories of the Greeks.

At the museum, none of the students—all 17 and 18, and thinking about the future—thought they wanted to be scientists. These are students who said they loved learning about botany, medicine, engineering. One even designed entire science curriculums for kids at summer camps.

“Astronomy was really cool, because I’m obsessed with the stars,” says Kavanaugh.

Kavanaugh and her classmates are exactly the kinds of students you’d want pursuing STEM degrees. And yet Jessie says she feels like she won’t fit into the way science is done.

“I don’t want to do Western science,” she says. “I don’t want to have to write everything down all the time. I keep it in my head because it’s in my blood to do that, you know?”

In 2012, the Obama administration set a goal of increasing STEM undergraduate degrees by 1 million to meet growing economic and technology needs in the next decade. But how do you recruit that many young scientists? And how do you invite everyone—like Kavanaugh and her classmates—who feels left out? Pantalony says broadening the image of science—and who does it—is a first step. He recommends giving credit to more non-Western scientists, both past and present—not to mention looking beyond the stereotypes of lab coats, test tubes, and particle accelerators.

“When you find out what science really is—observing, making, doing, asking good questions, failing…” he says. “That’s what I love about science. You hear that from kids and you hear that from Nobel Prize Winners.”

Jordyn Hendricks, another student at the museum, is Métis from Red River Nation. They say that recognizing the contributions of Indigenous people to science and technology matters for its own sake.

“We’re seen as primitive or not super smart. But we were super smart,” Hendricks says. “And it’s important to bring that in and recognize it.”

For both Lee and Buck, bringing star stories to the mainstream halls of Canadian science museums isn’t just about sharing Indigenous knowledge with Western visitors, or expanding the vision of what science is. It’s also about the future of Indigenous communities, still recovering from the damages of colonization.

In both Canada and the U.S., Indigenous youth have the highest suicide rate of any other racial or ethnic group. Indigenous communities have also been hit hard by the opioid epidemic, and young Indigenous people also have high rates of homelessness.

Literally, and figuratively, Lee says, youth are leaving. There is a lack of hope.

“That’s part of what the star knowledge brings,” she says. “This sense of purpose, the sense of hope, this lifeline, that each person is connected. To the bigger whole, the universe, the stars. Those stars are more than just balls of gas. When we do Indigenous science, those stars are our oldest relatives.”

“I found a piece that was missing from my life.”

Lee says this sense of connectedness is a unique part of Indigenous science. In Western science, knowledge is often considered separate from the people who discover it, while Indigenous cultures see knowledge as intricately connected to people.

“So it’s not like we’re just outside observers watching this,” she says. “The key thing is we’re a part of it.”

Can stories about the stars bring broken communities back together? For Buck, that connection to his history was a key part of his thriving. As a teenager, his family was scattered by poverty and he was homeless on the streets of Vancouver. Then, Cree elders invited him and other youth back to Manitoba to learn about their culture.

“I found a piece that was missing from my life,” he says. “I found something that made sense to me. I found something that was ours.

“It was a powerful thing.”

It was a journey that led him, ultimately, to the stars.

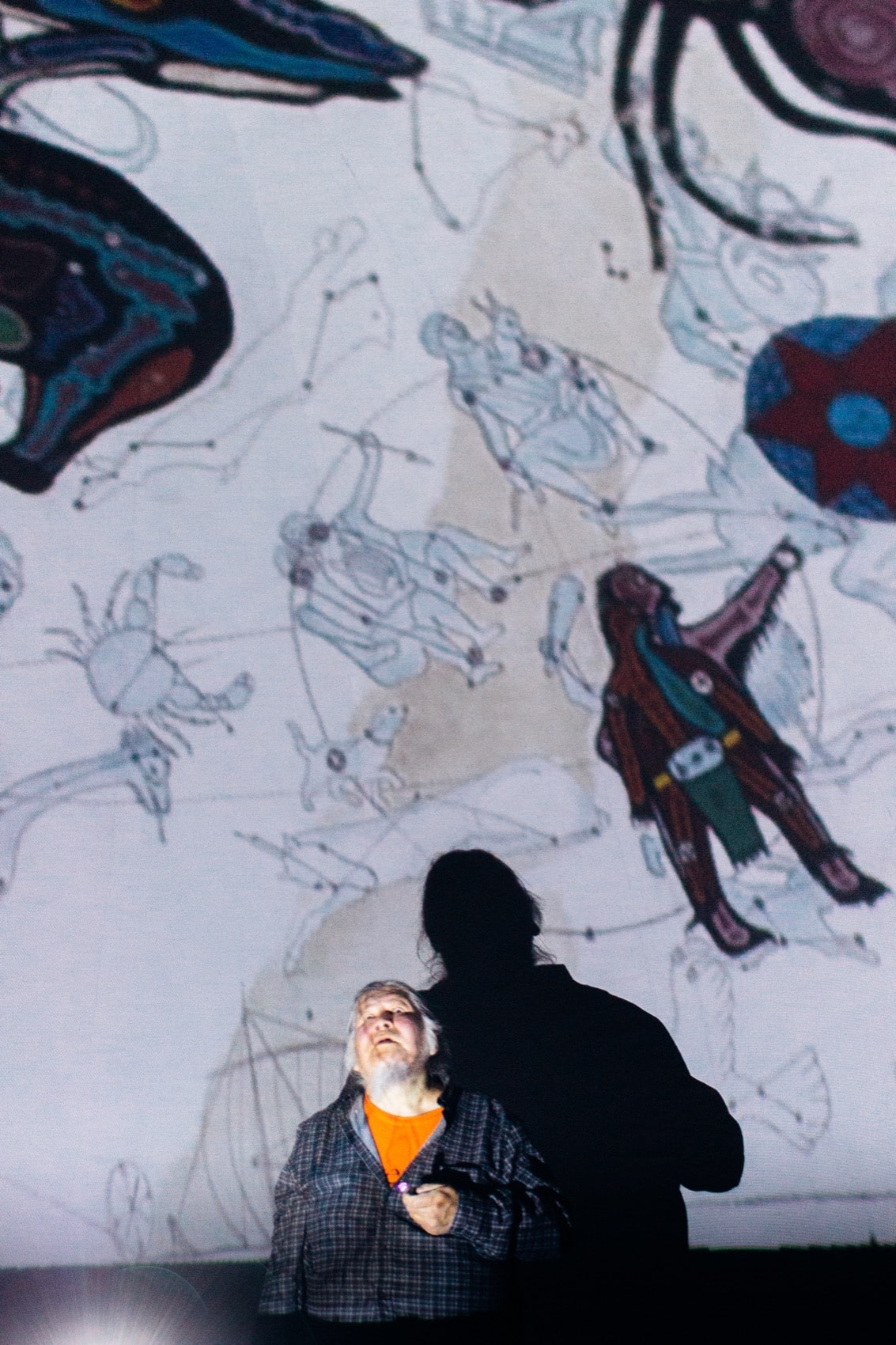

Buck gazes up at Cree constellations in his inflatable planetarium. Credit: Christie Taylor

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.