A Black Hole Meal, an Ancient Peach, and New NIH Rules for Animal Experiments

11:16 minutes

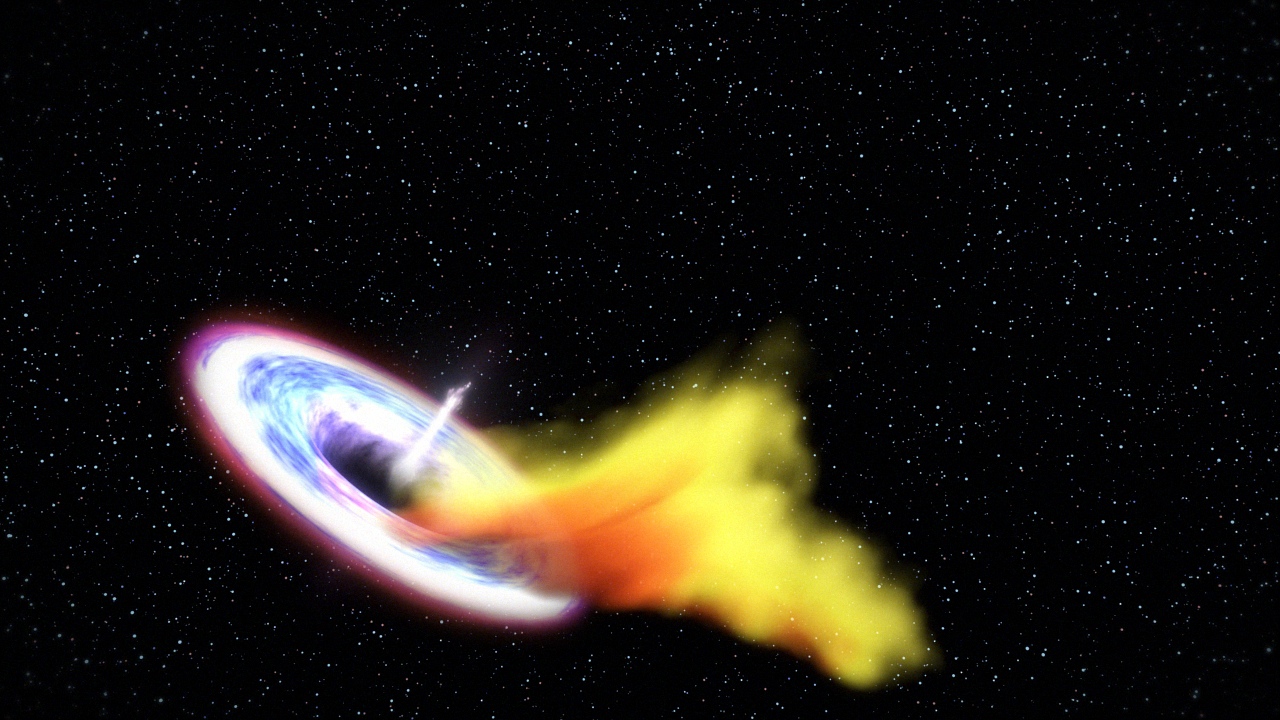

Scientists have seen black holes devouring stars before. But recently, astrophysicists captured the immediate aftermath of this stellar snack for the first time: a jet of matter launched from the black hole at almost the speed of light. Rachel Feltman, who writes for and runs the Washington Post’s “Speaking of Science” blog, aptly described this event as “a hot plasma burp.” Feltman discusses what scientists are learning about black holes from this rare sight. She also shares other selected short subjects in science, including the discovery of 2.5 million-year-old peach pits in China.

And starting next year, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) will require scientists seeking funding from the organization to include more female cells and female animals in their biomedical preclinical research. When it comes to the clinical trials funded by the NIH, women account for a little over half of the participants. However, research happening at the cellular and animal level remains overwhelmingly male. While many are lauding the NIH’s move to consider the variable of sex in these studies, others are concerned that the new policy will fail to make a meaningful difference where the health outcomes of men and women are concerned. Science reporter Azeen Ghorayshi, who covered this story for BuzzFeed News, looks at the positives and negatives of considering sex as a biological factor in animal studies.

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

Azeen Ghorayshi is a science reporter for BuzzfeedNews in New York, New York.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

A lot is made of the differences between men and women, right? Especially when it comes to their biology. But when it comes to the brain in particular, it turns out that this organ can’t be constrained by the typical male and female categories.

A new study published in the proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week finds that our brains are often a little bit male, a little bit female, and a lot in between. Here with more on what the researchers described as “mosaics of features” as well as other selected short subjects in science is Rachel Feltman. She writes for and runs the “Speaking of Science” blog at the Washington Post. Good to see you Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Good to see you too, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: “Mosaic of features”.

[BOTH CHUCKLE]

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, so basically this study is arguing that at least when it comes to the brain, it’s time to throw out the gender binary. Obviously, there are some features that are more typically male, more typically female. Male brains are larger. There’s difference in ratio of gray to white matter, differences in the size of certain structures.

But this study was the first one to look at a large number of scans, looking specifically at these supposed male-typical, female-typical structures, and what have you. And they found that it’s really exceptionally rare for a brain to have all the male-type structures or all the female-type structures– or even all ones that are somewhere between the two. It’s much more likely to have a mosaic.

And you could argue, oh, this doesn’t mean anything. Brain structure doesn’t necessarily relate to behavior. But we already knew that that was true. But the point is, it’s hard to take those structures and turn them into a male brain and a female brain. It’s much more complicated than that– and much more interesting.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because now we have the other word “gender” to deal with. True, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, and gender is already such a weird, confusing, interesting concept. So adding this to the mix is going to make for some really interesting studies in the future, I think.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to this idea that– well, I found it was very intriguing. Because I know that no one can hear you scream in space, as they say in the movies. But can they hear you burp– especially if you’re a black hole?

RACHEL FELTMAN: If you’re a black hole, they can hear you burp, apparently. A study looked at a black hole about 300 million light years away. And black holes consume stars all the time. We know this. We’ve seen it. But this is the first time that we’ve seen the entire process. Looking at radio signals from the black hole, researchers were able to see this black hole jet that gets admitted after a star is consumed. It’s kind of like a hot plasma burp of some of the material that it consumed from the star.

And it’s just very exciting, because we’d seen these jets before. They were quite sure that they were the result of stars being taken in by black holes. But this is the first time they’ve really seen the whole connected process. So it suggests that this is indeed where these jets of hot plasma come from and that we’ll be able to see more of them as we look for the radio signals on other black holes.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. OK. So burping black holes, like they’ve had a bad meal.

Have researchers found evidence– and this was really interesting– of a real-life Loch Ness Monster?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, sort of. So on the Isle of Skye, researchers found the largest ever set of evidence of dinosaurs– specifically sauropods, relatives of our beloved brontosaurus among other long-necked plant eaters. It’s about 170 million years old, and they’re footprints. They’re the first sauropod footprints ever found in Scotland. They look like these big pot holes, and some of them are as much as two feet across.

And what’s cool about them is that they’re in an area that used to be kind of a swampy beach. And that’s interesting if you know about the history of sauropods. We used to think that their bodies were so weird that they couldn’t possibly support their weight unless they were aquatic.

IRA FLATOW: That’s why they were in the water all the time– to hold them up.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Right. And then they were redeemed as land dwellers. Scientists figured out that they could actually support their own weight. But now we see that even though they did spend most of their time on land, they apparently liked to wade in the water occasionally. The scientists think they were probably looking for food or hiding from predators. But for whatever reason, they were at the beach in Scotland, and they’re pretty Nessy-like. I would argue.

IRA FLATOW: Now this was not a recent sighting. Right?

[BOTH CHUCKLE]

RACHEL FELTMAN: No. This was 170 million years ago.

IRA FLATOW: So 170 million-year-old footprints on the shores of areas that were lakes– but not Loch Ness itself.

RACHEL FELTMAN: No.

IRA FLATOW: See, that’s the thing.

RACHEL FELTMAN: The Isle of Skye.

IRA FLATOW: I want to make sure that we get that one in.

[BOTH CHUCKLE]

And last up, I saw this on the internet– a super old peach, a peach of a find in China.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes, in southwestern China in an area by a bus station where construction had unearthed this rock from the Pliocene. So they’re 2.5 million years old, these eight peach pits. And what’s exciting about them is that they are basically identical to the pits found in modern peaches. So the scientists can’t actually reconstruct the fruit, so they’ve named them as a new species since they can’t be sure. But they’re pretty certain that these peaches were really like modern peaches, maybe just a tiny bit smaller.

And that’s exciting because they’re 2.5 million years old, and humans only started cultivating things maybe 10,000 years ago. So it’s an indication that the peach, as we know it, pretty much got to where it is today through natural selection and not with much help from humans. And it’s also a pretty good indication that the peach did originate in China, which people have long suspected. But until now, the oldest evidence was about 8,000 years old. So obviously, 2.5 million is a big improvement.

IRA FLATOW: What really struck me about looking at these fossils is how they look exactly like a peach pit, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: They look exactly the same.

IRA FLATOW: But they’re millions of years old.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. You’d think that lot of times, they just find a print of something like a two dimensional thing on a rock. But this time, they found a whole peach pit.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Right. And all of the dating checked out in addition to being in this layer of rock that is definitely 2.5 million years old. The pits do also seem to be of that age. So the peach has a long and delicious history– much older than humankind.

IRA FLATOW: There you have it. It’s the pits.

[BOTH LAUGH]

IRA FLATOW: But it’s good this time. Thank you, Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman, is a writer, and she also runs the “Speaking of Science” blog at the Washington Post.

Now it’s time to play “Good Thing, Bad Thing”.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Over 20 years ago, the National Institutes of Health created its Office of Research on Women’s Health to increase the number of women and ethnic minority groups in clinical studies. And today, women make up a little over half of the participants in NIH-funded studies– a big improvement, and it goes along with the population.

But when it comes to laboratory studies, the subjects are still typically male– male mice, that is. So NIH is rolling out a new policy in 2016 that seeks to increase the number of females at this level of research. And while parity between the sexes– be they human or mice– sounds good on the face of it, some researchers have concerns about the changes.

Here to talk about the good and the bad of the policy’s shift at NIH is Azeen Ghorayshi. She is a science reporter for BuzzFeed News in New York.

Welcome back to the program.

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: All right. So the good thing about this?

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: Right. So like you said, traditionally female animals have sort of been excluded from preclinical research because it was thought that their hormonal cycles could muddle the data. So most research was done using male animals. With the rise of a women’s health research movement, they said, look, this is paternalistic. This is also biased. And we’re also seeing differences in outcomes for women’s health, possibly due to the fact that we don’t know that much about how female biology works.

So one of the things they brought up was, for example, heart attacks. In young women who have heart attacks, they are twice as likely to die as young men. And then they also brought up the case of Ambien which in 2013, the FDA actually had to slash the dosage requirements for women in half because all these women were sleepwalking. They were driving very, very drowsily. They were even having sex while they were asleep. And all of this, they say, is due to the fact that we’re not really putting in the work ahead of time to understand how female biology differs from male.

IRA FLATOW: So this was good intentions that they had.

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: Right.

IRA FLATOW: But the bad news?

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: So this is a paper that came out a couple weeks ago in PNAS. They’re arguing that requiring across the board that people who are doing preclinical research look at sex could bring up sex differences that don’t really exist in humans. So first of all, we don’t really know what sex means at the level of cells or at the level of animals and how that sort of translates to sex differences in humans.

Second of all, they say that a lot of the differences we see, particularly in health inequities between men and women, have to do with social causes. So for heart attacks, for example, women are less likely to think of heart attacks as a female disease, so they are less likely to phone it in. They’re less likely to go to the doctor, even when they’re having symptoms. In the case of Ambien, for example, it took studying it in embodied humans to understand that it was not actually a sex difference, it was a difference in body weight that had to do with how quickly the Ambien was metabolized.

And then the last point, actually, that she makes is back to what Rachel was talking about earlier is that the history of studying sex differences in science is sort of fraught. In the 19th century, for example, they studied the size of different parts of female brains to sort of justify certain stereotypes– also in ethnic minorities, such as African-Americans. That turned out to be damaging. And we have to think about whether we’re asking the right questions and really make sure that if we are going to be studying sex differences, that we’re doing it in the right way.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, we should. So don’t spend so much time in the Petri dishes studying the sex differences after you apply it to clinical or real cases.

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: Right. Definitely. They specifically said, we don’t even know what sex means at the level of something that’s in a dish.

IRA FLATOW: And then we get back to that whole gender question.

AZEEN GHORAYSHI: Yeah– which is a whole other, obviously.

IRA FLATOW: That’s quite interesting. Thank you very much for joining us today.

Azeen Ghorayshi is a science reporter at BuzzFeed News here in New York.

Copyright © 2015 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our polices pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

Becky Fogel is a newscast host and producer at Texas Standard, a daily news show broadcast by KUT in Austin, Texas. She was formerly Science Friday’s production assistant.