A Jovian Arrival, Titan’s Chemistry, and a Goat’s Gaze

7:25 minutes

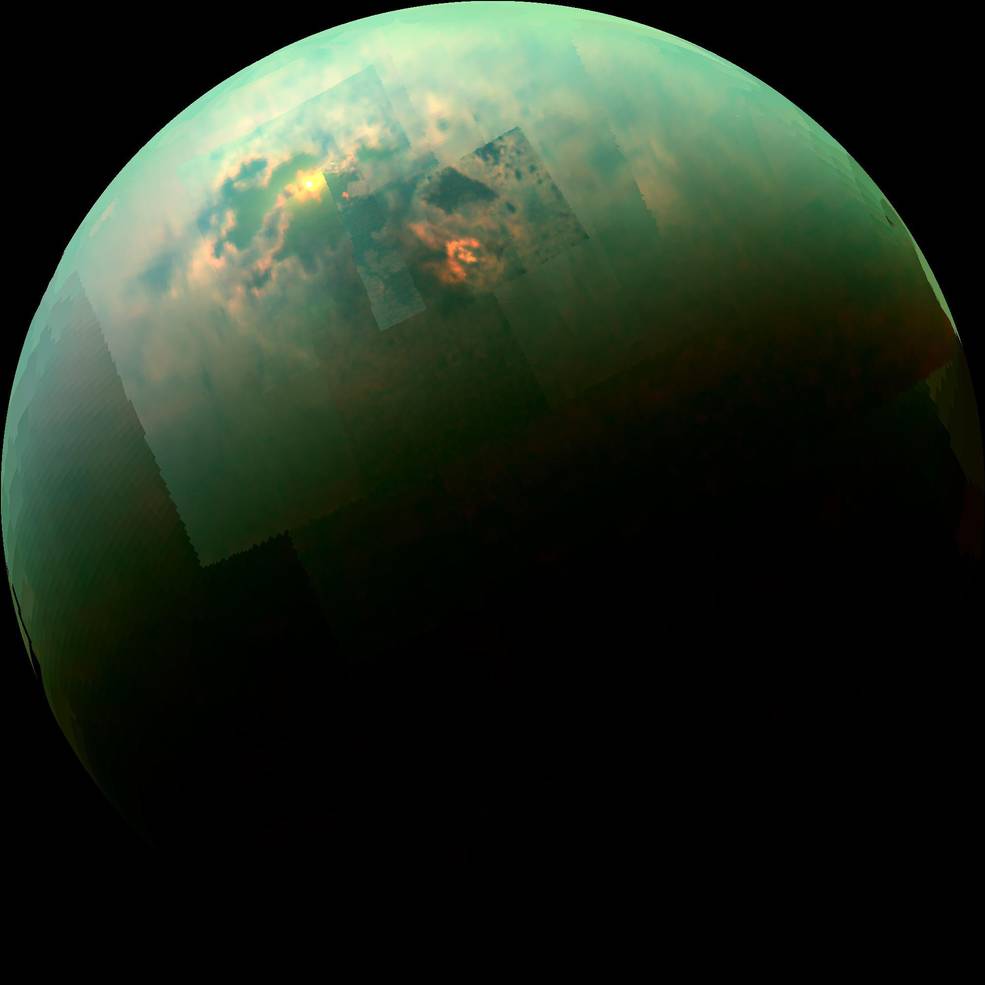

Researchers have found that Saturn’s moon Titan could have the right chemical conditions to create precursors to life, although the chemistry — based on hydrogen cyanide and a molecule called polyimine — wouldn’t lead to life as we know it here on Earth.

Rachel Feltman, editor of the “Speaking of Science” blog at The Washington Post in New York, says Titan — Saturn’s biggest moon — is one of the most exciting moons in our galaxy and it’s beginning to challenge our concepts of what life might be like outside planet Earth.

“Titan is one of Saturn’s moons … and it’s a really exciting moon,” Feltman says. “It has the only stable liquid on the surface of anything other than Earth in the solar system that we know of. It has lakes and rivers and oceans, but they’re all full of methane instead of water. And has this really thick atmosphere, but it’s, you know, very different from our own. And there’s a lot of hydrogen cyanide produced in that atmosphere when the sunlight hits it.”

Scientists have been conducting research to figure out what conditions might be like on Titan.

“These researchers basically modeled how hydrogen cyanide might act in the super-cold environment of Titan and they think that it might form this polymer called polymine that under Earth conditions is not a very exciting polymer. But under Titan’s conditions they think it might have some of the qualities that might make it an intriguing candidate for a building block of life. You know, the way certain polymers helped create amino acids on early Earth.

“So they don’t know this for sure, they haven’t even modeled exactly how it happened. But it’s an interesting thing to look into, you know, how life might be completely unrecognizable to us on other planets. Because when the conditions are so different, the chemistry that goes into life will be so different,” Feltman says.

Titan is not the only moon in our solar system that scientists are interested in studying to try to learn more about possible life outside planet Earth. Europa, the sixth closest moon to Jupiter is also intriguing to researchers.

“A lot of planetary scientists would love to see us go to Titan,” Feltman says, “And there is the Europa mission coming up or tentatively coming up in the 2020s and you know that’s a slightly different world because it’s a subsurface ocean. But it’s a very similar idea that these moons with oceans on them are probably really great places to look for life … And Ganymede is thought to have an ocean under the surface. There’s really so many moons that we should be going to.”

Rachel Feltman is a freelance science communicator who hosts “The Weirdest Thing I Learned This Week” for Popular Science, where she served as Executive Editor until 2022. She’s also the host of Scientific American’s show “Science Quickly.” Her debut book Been There, Done That: A Rousing History of Sex is on sale now.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday, I’m Ira Flatow. Last Monday, as you’ll recall, was the 4th of July, and, while many of us had our eyes on the skies for fireworks, a team of planetary scientists had their eyes cast a little further out to Jupiter, where a new space probe Juno was about to arrive. Here to talk about that and other short subjects in science is Rachel Feltman, editor of the Washington Post Speaking of Science blog. Welcome back Rachel.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thanks for having me, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: The big story from the late 4th of July was Juno arriving in Jupiter, right.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes, it was a really impressive arrival. When you think about it, this was a spacecraft that was going upwards of 125,000 miles per hour as it approached the orbit. It needed to hit a target just a few miles wide, within a span of just a few seconds, to get the optimal orbit to carry out the scientific mission that they had planned, and it hit within one second and one centimeter of the target, which is just like very, very exciting.

IRA FLATOW: Pretty good shooting?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, pretty good. I did have some people say, well it was late and off target, but I think they did pretty well. So yeah, now we have to wait until around the end of August, the next time the probe is really close to Jupiter and it will start really collecting data in earnest. But they did collect some data before they turned off the instruments in anticipation of the orbital entry. So NASA has said that they’re already starting to comb through that and there’s a chance they’ll find something interesting even before the big data dump begins.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, a lot of planetary science this week. Another favorite, the New Horizons mission that visited Pluto has got a new place to head, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, which is actually part of the same program that Juno is, the same NASA program, and, as everyone remembers, last year New Horizons flew by the Pluto system and ever since the mission team has been working on redirecting it towards a new target out farther in the Kuiper Belt, this even more mysterious object. And NASA has just officially extended the funding so that they’ll definitely be able to make it there, and it’s supposed to reach, I think, on New Year’s Day 2019, so that’ll be another very exciting space holiday.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah because they say Pluto is just another piece of the Kuiper Belt.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, yep. There’s a lot of stuff to explore out there. And there were a couple other exciting mission extensions, Opportunity was extended yet again. It’s more than 12 years old now.

IRA FLATOW: The Mars Rover?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes. It was supposed to last three months and it’s more than 12 years old, no sign of stopping.

[CHUCKLING]

RACHEL FELTMAN: And Dawn, which orbited Vesta in Series was extended, which apparently was nobody anticipated a year ago that the spacecraft would last. They actually considered sending it to orbit a third body, but decided that they would get more out of staying around Series. But that mission has been extended too.

IRA FLATOW: And tell everybody what Series is.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Series is a dwarf planet. It’s one of the many bodies in the solar system that helped get Pluto demoted.

[CHUCKLING]

IRA FLATOW: Well my planetologists don’t consider Pluto demoted.

RACHEL FELTMAN: No, a dwarf planet is just another thing. It’s not a lesser thing.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Well while we’re out there in the solar system, there’s a study this week talking about the potential for life on Titan.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes. So Titan is one of Saturn’s moons.

IRA FLATOW: The biggest, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes. Hence the name. And it’s a really exciting moon; it has the only stable liquid on the surface of anything other than Earth, in the solar system, that we know of. It has lakes and rivers and oceans, but they’re all full of methane instead of water. It has this really thick atmosphere but it’s very different from our own, and there’s a lot of hydrogen cyanide produced in an atmosphere, when the sunlight hits it. So these researchers basically modeled how hydrogen cyanide might act in the super cold environment of Titan.

And they think that it might form this polymer called a poly-mime, that under Titan conditions– under Earth conditions, not a very exciting polymer, but under Titan’s conditions, they think it might have some of the qualities that might make it an intriguing candidate for like a building block of life. The way certain polymers helped create amino acids on early Earth. So they don’t know this for sure. They haven’t even modeled exactly how it happened, but it’s an interesting look into how life might be completely unrecognizable to us on other planets because when the conditions are so different, the chemistry that goes into life will be so different.

IRA FLATOW: So they’re not planning on a spacecraft going right now?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Well, I mean, there are no immediate plans in the works, but, I mean, I know of a lot of planetary scientists who would love to see us go to Titan. And there is the Europa mission coming up, or tentatively coming up, in the 2020s, and you know that’s a slightly different world because it’s a subsurface ocean, but it’s a very similar idea that, you know, these moons with oceans on them are probably really great places to look for life.

IRA FLATOW: And intelligence too, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And Jupiter–

RACHEL FELTMAN: And Ganymede is thought to have an ocean under its surface. There’s really– there are so many moons that we should be going to.

IRA FLATOW: I remember I was talking to Alan Stern, who was the head of one of a lot of Planetary Science at NASA, and he said earth is the outlier, in the solar system, because we have our ocean on the outside.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah, it really is. But Titan has an ocean on the outside too so–

IRA FLATOW: But it’s not a water ocean, right?

RACHEL FELTMAN: No, it’s methane.

IRA FLATOW: All right. Let’s talk about bringing back home a little more. You wrote about the surprising, adorable thing that goats– I’m not making this up folks, goats and puppies have in common.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Right. So there’s this thing that dogs and horses are known to do, which is they use their gaze to communicate with humans, specifically for– basically, the best way to describe it is when a puppy wants something and they can’t get to it, they, kind of, look to you, and look to the thing they want, and look back to you, and give you those puppy eyes. You know, they’re trying to direct you with their gaze to help them. And it turns out that goats do this too, which is surprising in some ways and not surprising in others.

It’s been thought that this gaze behavior is related to domestication, and goats are some of the oldest domesticated animals. After dogs, they’re the oldest we know of. They’ve been domesticated for about 11,000 years. So it makes sense that if it has to do with domestication, goats would have it.

On the other hand, horses and dogs were both domesticated as companion animals. So it makes sense that they would learn to socialize with humans. Goats, on the other hand, were bred for meat, and milk, and their hair. So it’s really interesting that they seem to have also learning to interact with humans in, you know, a positive way. And, you know, they’re probably a lot smarter than most people give them credit for. And these researchers really want to better understand the mind of the goat.

IRA FLATOW: So the goats will look at you and back at the thing just like a dog will.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yeah. Yeah, it’s really cute there’s a video of it. They will implore you to help them get treats.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

RACHEL FELTMAN: And, apparently, they do act very puppy like. They’ll like want you to scratch them.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have one?

RACHEL FELTMAN: I don’t have a goat.

IRA FLATOW: It’s tough in New York to. There are people who do, I am sure.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman, as always, a pleasure to have you.

RACHEL FELTMAN: Thank you, Ira.

IRA FLATOW: Rachel Feltman, editor of the Washington Post’s Speaking of Science blog.

Copyright © 2016 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of ScienceFriday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies.

As Science Friday’s director and senior producer, Charles Bergquist channels the chaos of a live production studio into something sounding like a radio program. Favorite topics include planetary sciences, chemistry, materials, and shiny things with blinking lights.