How This Chemist Is Turning Agricultural Waste Into Water Filters

7:18 minutes

Activated carbon filters have become common household items as water filters in pitchers, or directly on your faucet. These activated carbon filters are also used in industrial processes like wastewater treatment and to filter out chemicals released in smokestacks.

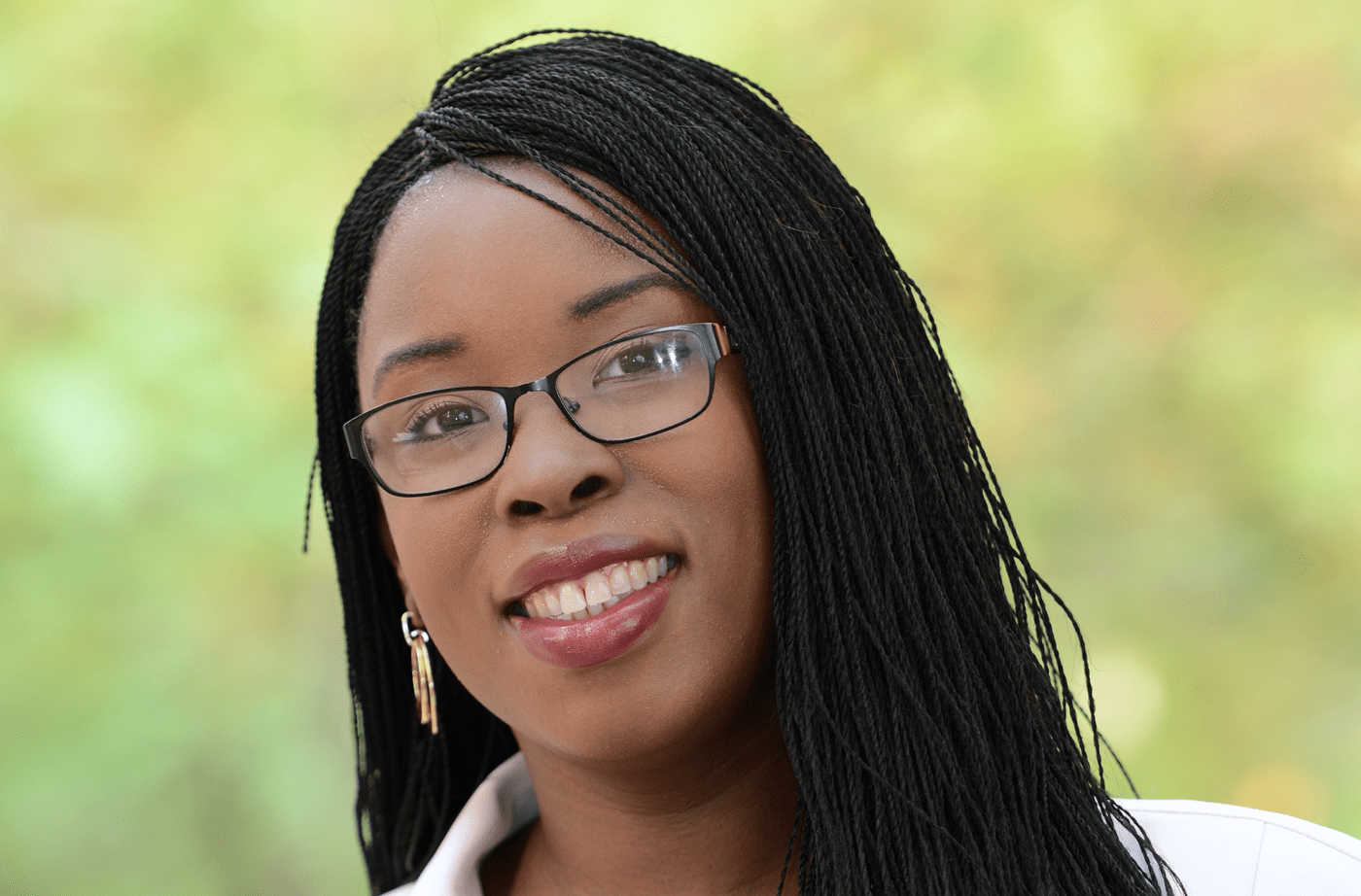

Dr. Kandis Leslie Abdul-Aziz, assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering at University of California Riverside, has created activated carbon filters from agricultural waste like corn stover and orange peels.

Abdul-Aziz talks with Ira about her research, and what it will take to shift manufacturing processes to be more sustainable and less harmful to the planet.

Further Reading

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Kandis Leslie Abdul-Aziz is an assistant professor of Chemical and Environmental Engineering at the University of California – Riverside in Riverside, California.

IRA FLATOW: You’ve probably seen or maybe you’re even using an activated carbon filter or two. That’s the filter in your water pitcher that you probably should change more often than you actually do. It’s also that black filter in your air purifier removing chemicals from the air. These are activated carbon filters. And they aren’t just in your home. They’re used in wastewater treatment and smokestacks.

But what if we could create these filters using recycled materials? My next guest is working on this. She’s so far made activated carbon filters from agricultural waste, meaning corn husks and orange peels. Joining me now to talk more about her research is Dr. Kandis Abdul-Aziz, assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering at UC Riverside. That’s based in Riverside, California. Dr. Abdul-Aziz, welcome to Science Friday.

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: All right. Thank you, Ira. I’m glad to be here.

IRA FLATOW: As I mentioned before, you turn husks and stalks and leaves into carbon filters. How did you land on corn waste?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Yeah, so corn waste is actually the top agricultural waste that’s produced from the United States. I went to school in University of Illinois, so I’m very familiar with all of the corn fields around. And so that was one of the first initial problems that we wanted to utilize, was to see if we can do something with all of the corn waste that’s generated.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm, and how do you turn corn husks into carbon filters? I know that if you put a match to a corn husk, it’s going to start burning and turning black, but that’s not what you do, is it?

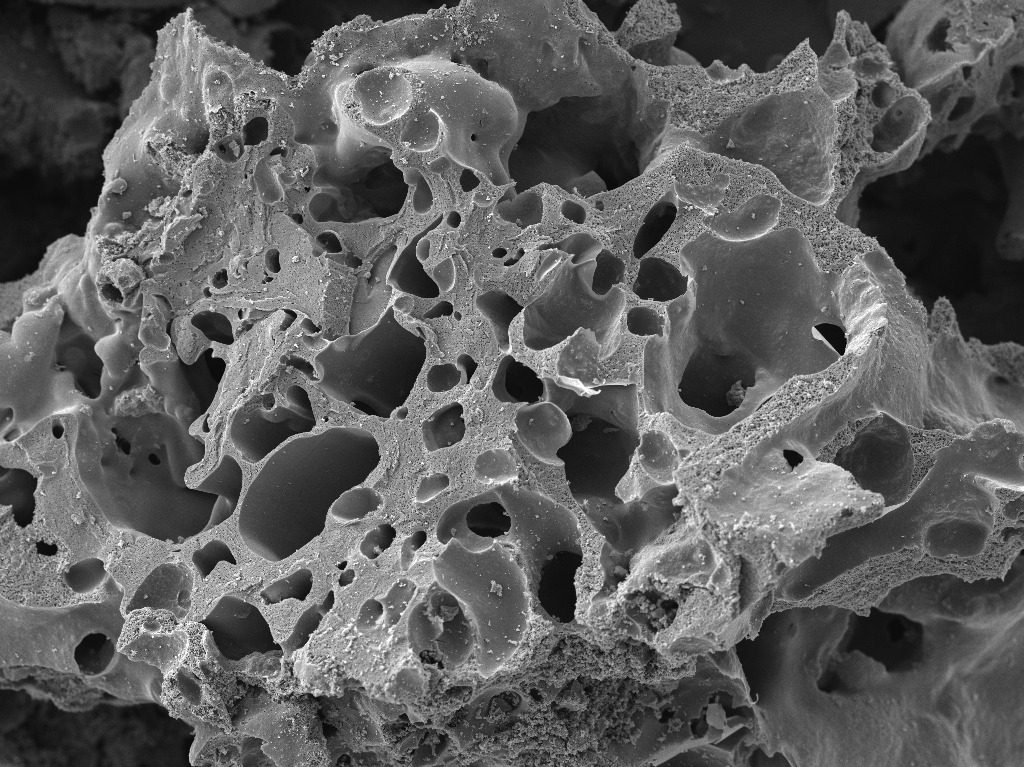

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: No, so my laboratory at UC Riverside, we’ve actually developed a process that can break down corn husks and even citrus peels into solid carbon. And so what we do is we do some chemical modification of that solid carbon and creates this pore structure, which is then called activated carbon. And you can utilize activated carbon in all of these different cool applications.

IRA FLATOW: Now let’s talk about some of those cool applications. Name a few really good ones for us.

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Sure, so one of the ones that people are most familiar with is water filtration. In fact, my laboratory has been studying how we can modify activated carbon filters from agricultural waste and utilize that to remove different water pollutants. Another way also is for air purification. So you can use activated carbon filters, say, in your car to purify the air that’s going– while you’re driving your vehicle.

IRA FLATOW: Hm. Now I understand that you can actually filter out PFAS, which is everywhere, right?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: When we first started working on the development of these activated carbon water filters, we were looking at the removal of different phenolic compounds because those are typically what you see from industrial waste. But we talked with some people at water municipalities, especially in Southern California, where we’re located, and PFAS seemed to be one of the things that were on a lot of these municipalities’ minds in terms of removing that from wastewater. And so we’ve recently started looking at the removal of PFAS from wastewater and in terms of trying to modify also the activated carbon properties so that we can do that effectively as well.

IRA FLATOW: You mentioned that you were turning orange peels into carbon filters using a similar process. I would imagine that being in California, all those orange groves, that’s where you get your peels from, right?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Yes, absolutely. So just around the corner from my house, we have an orange grove. And we had the idea of we’re in Southern California. We want to benefit the local industry here as well. And so we wanted to turn those orange peels, which are normally discarded or used for cow feed, and see if we can also utilize that for activated carbon. And actually, one of my doctoral students just went to the citrus grove that’s around the corner from my house and got a trash bag full of orange peels. And we’ve been utilizing that for a lot of our experiments.

IRA FLATOW: They must have been more than happy to give it to you.

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Yeah, they were very happy.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: What are activated carbon filters typically made from? And why should we be using recycled ones, coming up with new materials, like you are, like corn husks or orange peels instead?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Typically, activated carbon is usually made from either coal or coconuts. Now, coal, I mean, if we’re trying to get away from coal as an energy resource, then it would be more advantageous for us to utilize something that’s sustainable, like agricultural waste. Additionally, we utilize coconuts, but most of it is actually exported. And so the usefulness of developing activated carbon filters from agricultural waste, especially ones that are locally sourced, is that it can be sourced from the United States.

IRA FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Now when can I get these filters in the store? I mean, I imagine you’re just in the research phase, right? But people must be asking you all the time, hey, I want to get some of this stuff.

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Yeah, there’s actually a lot of interest into these renewable activated carbon filters. However, we’re still doing significant amount of research. And in particular, we want to start upgrading them in terms of making them more beneficial for water treatment facilities, so making them in a controlled particle size, like granular size.

In addition to that, we want to see what the effects of these different growth seasons could have on the activated carbon because that’s probably one of the main issues, is that you could have sort of a heterogeneity in sort of the growth cycle. And we expect that should also transform into modifying the properties of the activated carbon that’s coming out of these agricultural resources. And so now we’re trying to look into that as well.

IRA FLATOW: You sound like a carbon expert. What’s on the carbon frontier, the carbon capture frontier that you would like to see happen?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: A big thrust of the research that we’re doing is developing sorbents that are able to remove greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane out of the air. And we’re actually trying to utilize that as building blocks to make similar materials that we’re making today out of fossil fuels. So that’s something that’s really exciting for us.

IRA FLATOW: When you capture it in the carbon, does it stay in the carbon? I mean, could you use it to build other things with it and lock it up forever?

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: So for example, we have a material that can capture carbon dioxide and turn into a carbonate, which is basically solidified carbon. And so you can store it as a form of rock. That’s something that’s being studied right now. We’re on the other end of it in terms of we’re trying to make some uses of the captured carbon. So capturing CO2 and methane and converting that into synthesis gas, which is often a building block to make further things like gasoline or to make ethanol or ethylene, which can also be building blocks to make other materials like polymers as well.

IRA FLATOW: Sounds very interesting. Wishing you a lot of luck on this, Dr. Abdul-Aziz. Thank you for taking time to be with us today.

KANDIS ABDUL-AZIZ: Yeah, thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Kandis Leslie Abdul-Aziz, assistant professor of chemical and environmental engineering at UC Riverside.

Copyright © 2023 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.