Why Did Ancient Ferocious Cat-Like Creatures Go Extinct?

7:50 minutes

Can you imagine a world without cats? No furry loafs adorning our sofa arms. And no bobcats, mountain lions or jaguars either.

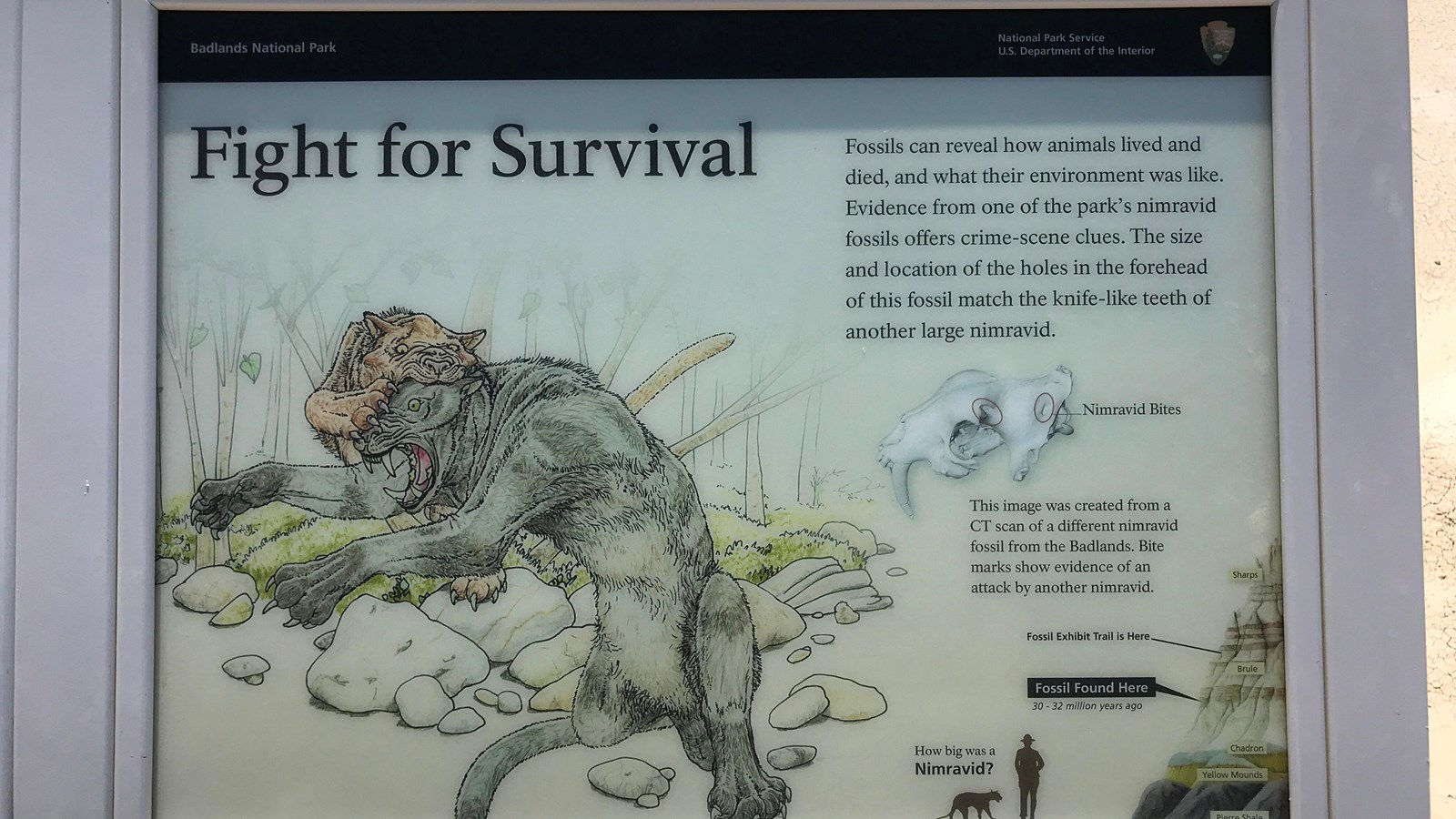

Before there were cats in North America, there were nimravids, also known as “false” saber-toothed cats (while they had elongated canines, they weren’t actually cats). About 35 million years ago, nimravids roamed all over North America.

But after 12 million years of dominating the continent, nimravids disappeared. For roughly the next 6.5 million years, there were no feline-like creatures anywhere in North America. This time period is called the Cat Gap.

But why did nimravids go extinct? Guest host John Dankosky is joined by Chelsea Whyte, assistant news editor at New Scientist, who’s based in Portland Oregon, to discuss her reporting on this feline-less era.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Chelsea Whyte is an assistant news editor at New Scientist. She’s based in Portland, Oregon.

JOHN DANKOSKY: This is Science Friday. I’m John Dankosky. Can you imagine a world without cats? I know I can’t. I’ve got four of them around the house and they’re always finding their way into my Zoom calls. But I’m not just talking about house cats here, no bobcats. No mountain lions or jaguars either.

Let’s go back in time a bit. Before there were cats in North America, there were cat-like nimravids, also known as false saber toothed cats. And about 35 million years ago they roamed all over North America. Then after 12 million years of dominating the continent they just disappeared. And for roughly 6 and 1/2 million years there were no feline like creatures anywhere in North America. It’s called the cat gap.

But why did it happen? Joining me now is Chelsea White, assistant news editor at New Scientist. She joins us from Portland, Oregon to discuss her reporting on this interesting topic. Chelsea, welcome to Science Friday.

CHELSEA WHITE: Hi, John. Thanks for having me.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So what made you decide to look into the cat gap?

CHELSEA WHITE: Well, it all started with a joke actually. I was joking with a friend that cats seemed eternal. And then I thought, well, they weren’t. I’m curious when they evolved and where they were in North America. And that led me to the Wikipedia page for something called the cat gap. And I had never heard of it. There were all of these interesting hypotheses for why the cat gap might exist. But I wanted to look into it more and see what sort of the consensus is in the scientific fields. What paleontologists really think might have happened.

JOHN DANKOSKY: I understand that while you were reporting this story, you actually had something of a cat gap yourself.

CHELSEA WHITE: I did. I did. My 18-year-old cat, Sienna, got out and went missing for five or six months.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Oh no.

CHELSEA WHITE: Yeah, it was a really hard time. But in that period was when I was reporting and writing the story about the cat gap. And then after I filed it, she turned back up. it was nice to have the end of my own little cat gap there.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Absolutely. So your reporting focuses on this cat like animal. It’s called the Nimravid. And as I said before, they’re also known as fake saber toothed cats. Not actually cats though, maybe you can explain exactly what these were.

CHELSEA WHITE: Right. So they’re not true cats. They’re not felines, but what we know as feliforms. So they look like a cat, but they’re not quite part of the family. And that means that a cat, like a true cat, they have retractable claws, they have a tail for balance, and they have specialized teeth for eating meat. But they also have these structures in their inner ears and some nerve passages and blood vessels that differ from cats. And they also walked flat footed like a bear instead of on their toes like you might see your house cat do.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Describe them a little bit more. I mean, were there really big ones and really tiny ones?

CHELSEA WHITE: They were all kind of fearsome creatures. But they ranged a lot in size because they ranged a lot in where they lived. Their fossils have been found across North America from east to west and also up and down the continent, even up into the Canadian Rockies. There’s a reason they were called false saber toothed cats. They had these very large canine teeth that were used for stabbing into prey.

There’s one called eusmilus, which translates to true saber. And that was about three feet tall, kind of a long bodied leopard. Their names are really evocative. There was one called pogonodon, which means beard tooth. And then the smallest one, nanosmilus was about the size of a bobcat. My very favorite name is dinictis, which just means terrible cat.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So these sound like some pretty fearsome creatures. If they were so fearsome, why exactly did they die out?

CHELSEA WHITE: So there was this hypothesis that potentially there was some ancient volcanic activity that could have done them in. But it turns out there was sort of this two pronged problem that they had. One is that there was a period of massive cooling and drying. And so what that meant is that their home forests turned into grasslands. And so that would have changed the way that they hunted. It would change the way that the prey that they hunted lived and survived. And when prey species go extinct, predators follow.

The other thing that happened is that nimravids had evolved to be hyper carnivorous, which means most of their diet was meat. I described for you their long saber tooth canine teeth, but they also had these teeth in the back of their mouth where their molars might be called carnassials. And these were triangular teeth that fit together sort of like puzzle pieces. And as they grind down together they sharpen. One of the researchers I spoke to called them horrible scissors. And what this means is that the nimravids really were only specialized to eat meat and they couldn’t adapt to the loss of their prey.

JOHN DANKOSKY: They’re not able to survive and then that precipitates this thing that we call the cat gap. How long was North America completely feline free once these nimravids went away?

CHELSEA WHITE: Well, the cat cap lasted for about 6.5 million years. And when it was first discovered, it was maybe thought to be a little bit longer. And as we’ve found more fossils, we find more and more in that cat gap has shrunk and shrunk. And the other thing that’s happened is that we have a lot of these fossils in museums already. And some of them have been classified as felines and then we go back and we reanalyze them and find actually these were nimravids.

JOHN DANKOSKY: So after 6 and 1/2 million years, all of a sudden we start to see cats repopulating North America. How did it end? Where do they come from?

CHELSEA WHITE: Right. So that period of cooling and drying that I talked about continued. And with that, the glaciers grew, the sea levels drop, and the Bering Land Bridge that once connected Siberia to Alaska emerged. And then came a cat called pseudaelurus, which is a Lynx sized cat from Asia. And this became the ancestor of felines in North America. Now after pseudaelurus came along, another nimravid came along. There was a group called the barbourofelis, they came after pseudaelurus. So it wasn’t like they ended the cat gap either. But then by 5 million years ago, barbourofelis were extinct again and now we just have felines, true cats.

JOHN DANKOSKY: And we have them all over North America, which is for us cat lovers exactly the way we like it. So now that you’ve looked into this fascinating part of history, what has this taught you about conservation about animal habitats?

CHELSEA WHITE: You know, it was interesting when I was speaking with some of the researchers about what the problem is with becoming hyper carnivorous, we started to compare it to some of the animals we see today. So one of the reasons bears do so well living amongst humans is that they can eat anything. They can eat berries and fish. They can also eat garbage.

And so that’s one of the reasons that we sort of have some conflict with bears and humans. But that’s why tigers these days cannot live quite so well in places where we are encroaching on their habitat. So it’s one of those things where it makes you think we do really need to be careful and save these sort of species otherwise we’re going to see them go extinct, like the nimravids did.

JOHN DANKOSKY: Chelsea White is assistant news editor at New Scientist. She’s based in Portland, Oregon. She brought us the story of the cat gap. Chelsea, thanks so much for your research and thanks for bringing this story to Science Friday.

CHELSEA WHITE: Thanks for having me.

Copyright © 2022 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

John Dankosky works with the radio team to create our weekly show, and is helping to build our State of Science Reporting Network. He’s also been a long-time guest host on Science Friday. He and his wife have three cats, thousands of bees, and a yoga studio in the sleepy Northwest hills of Connecticut.