Biden Declares The COVID-19 Pandemic Over. Is It?

12:17 minutes

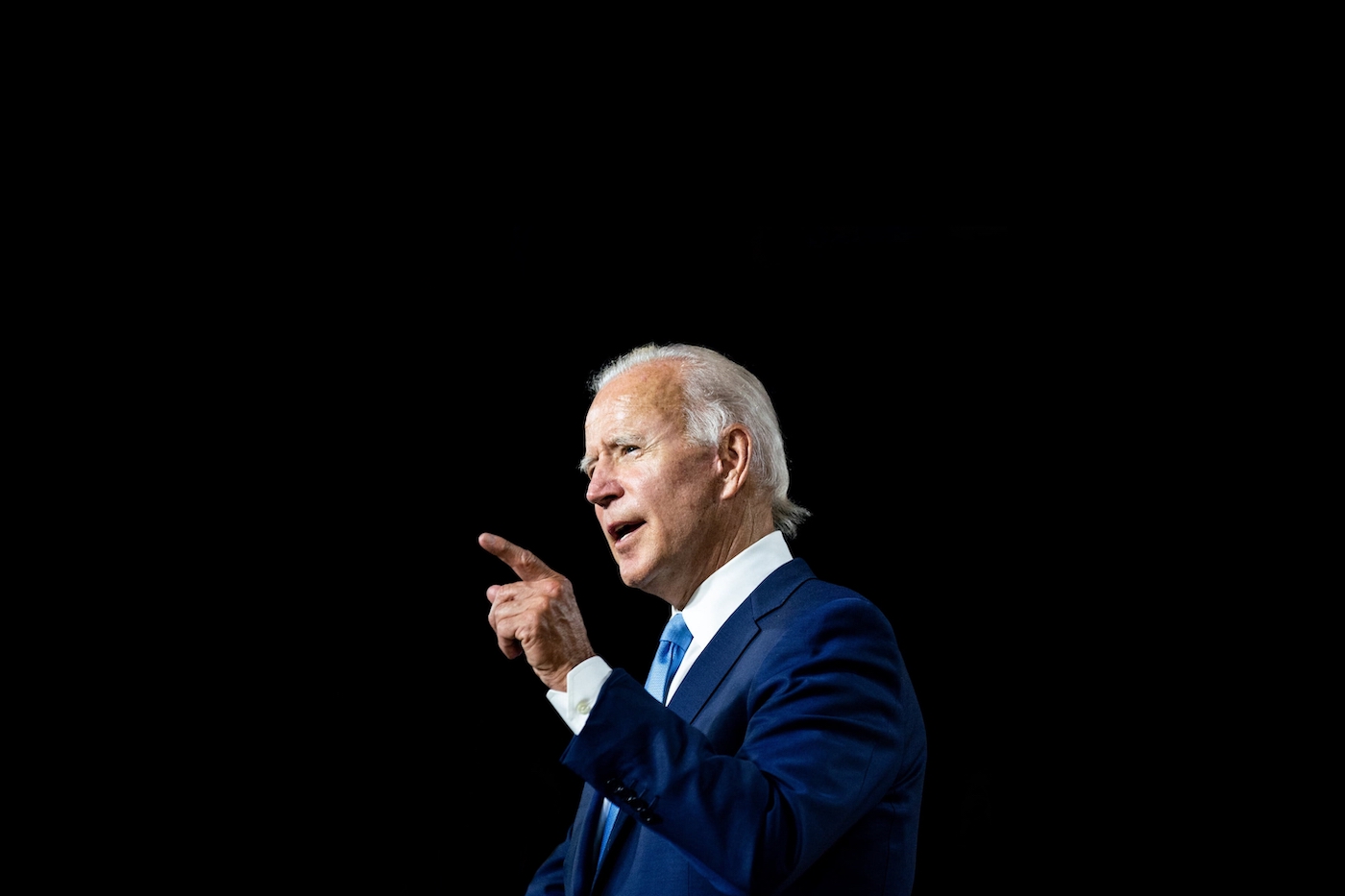

During an interview with 60 minutes last weekend, President Joe Biden said “the pandemic is over.”

“The pandemic is over. We still have a problem with covid, we’re still doing a lot of work on it. But the pandemic is over. If you notice, no one is wearing masks. Everybody seems to be in pretty good shape, “ Biden said at the Detroit auto show.

This comment has prompted some dismay from the public health community. The World Health Organization hasn’t declared the pandemic over just yet. And the criteria to declare a pandemic over is nuanced and cannot be declared by the leader of a single country.

Ira talks with Katherine Wu, staff writer at the Atlantic, about that and other top science stories of the week including a new ebola outbreak in Uganda, the latest ant census, and Perseverance’s rock collection.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Katherine Wu is a staff writer at The Atlantic based in Boston, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Later in the hour, diving into the biggest ideas in the universe with physicist Sean Carroll and how an exploding moon may explain the origin of Saturn’s rings. But first, during an interview with 60 Minutes, President Joe Biden said something that, understandably, made a lot of headlines.

JOE BIDEN: The pandemic is over. We still have a problem with COVID. We’re still doing a lot of work on it. It’s– but the pandemic is over. If you notice, no one’s wearing masks. Everybody seems to be in pretty good shape.

IRA FLATOW: This comment has prompted a lot of response from the public health community. The World Health Organization hasn’t declared the pandemic over just yet. How do we know when it’s over? Joining me now to talk about that and other science news of the week, Katherine Wu, staff writer at The Atlantic. She’s based in New Haven, Connecticut. Welcome back to Science Friday, Katie.

KATHERINE WU: Great to be here again. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re Welcome. Well, obviously, many public health experts disagreed with the president’s assessment, right? But how exactly do we determine when the pandemic is over?

KATHERINE WU: Oh, it is a great question with a very unsatisfying answer, unfortunately. I think the tricky thing with pandemics is there isn’t even a totally universal definition of pandemic. We just have this fuzzy sense of it’s a disease that is affecting the world on a global scale, pandemic, pandemos, all people being affected by something. That has certainly been the case, but it’s not like we say, oh, as soon as cases of x disease crest over y number, there’s a pandemic, and then once we go back below y number, we’re done.

It is definitely not that clear cut. There’s no super clear-cut demarcation. And you’re right. The WHO could lift the state of emergency. The US could lift its own. But it’s not up to one person, and even if it, were unfortunately, I don’t think it would be the president of a single country. Sorry, Joe Biden.

IRA FLATOW: But I think the president was on to something there when he said, no one’s wearing a mask anymore, because you do see very few people wearing masks.

KATHERINE WU: Yes, this is true, and I think some of the discussion that’s going on right now is, when do we sort of start acting like the pandemic is over? Because if we’re easing the psychological concept here, when do things feel like they’ve returned to normal, arguably, that has happened. Is that enough to say the pandemic is over?

But it’s kind of tricky here. A lot of experts have pointed out this week that the better question is maybe not if we’re saying the pandemic is over or not but what do we do about it? COVID is still a problem. Is this even the right question to be asking? Rather than debating the semantics, how are we going to live with a virus that is still killing hundreds of people, just in the US alone, every single day?

IRA FLATOW: Well, while we’re still on the infectious disease discussion, let’s talk about Ebola because there’s a new outbreak reported in Uganda. Tell me what’s going on there.

KATHERINE WU: Yeah, so officials this week reported that there has been one confirmed death and several others that they’re looking into. This is being caused by the Sudan Ebola virus species, which is one of the six species of Ebola virus known to humans. And this is really concerning. Sudan and Uganda are two of the countries that have had several outbreaks in the past few years, and this is yet another one that’s being added to the list.

IRA FLATOW: So should we be concerned about it spreading through Africa and possibly around the world?

KATHERINE WU: I think we should be concerned, but it is certainly not time to panic. I think what’s important to keep in mind is that this species of Ebola virus, the Sudan species, is just one of six types of Ebola. It is not the same species that caused the 2013 to 2016 epidemic in Western Africa, which killed more than 11,000 people. That was caused by a different species called Zaire.

But one reason to be concerned is the treatments and vaccine that we have developed against Ebola were all developed against that Zaire strain, which means that the Sudan Ebola virus, we may not have as many tools. So right now, it’s pretty important for the rest of the world to be invested and to send as much aid as possible.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s move on to your next story, but we’re going to still stay with pathogens. And this one is found in frogs. A new research study links a fungal infection in frogs to a spike in malaria cases in humans. How does that work exactly?

KATHERINE WU: Yeah, this is a fascinating story, and Maryn McKenna had a great piece about this in Wired for anyone who wants to learn a little bit more. But what’s going on here is this is a really fascinating story about how just food webs are so interconnected, and there’s a really interesting domino effect going on here.

So basically, let’s remember that malaria in humans is caused when mosquitoes carrying the parasite that causes malaria, the mosquitoes bite us. They introduce the parasite into our blood. Frogs are one of many animals that eat mosquitoes, and so when their populations decline, mosquito populations can boom. And that can be bad news for us if those happen to be mosquitoes that carry malaria.

And that is possibly what’s going on here. In Costa Rica and Panama, this fungal pathogen, nicknamed BD, has really been annihilating frog populations there. It’s actually caused more than 90 amphibian species to go extinct in the past few decades, and if it’s devastating these frog species in Central America, that is a big problem for us because we no longer have this natural form of mosquito control.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, yeah, and there’s another surge, I understand, of a similar fungal infection on the horizon.

KATHERINE WU: Right, so BD has a sister called B cell. And both of these are pretty problematic in the same way. They infect frogs and other amphibians. They get into their skin, and that can actually cause heart failure. Scientists haven’t yet figured out a really good way to stop the spread of this fungal pathogen, which means we could see a lot more loss of frogs and related species in the very near future.

IRA FLATOW: Oh, I hate hearing this kind of news. Let’s talk about some really interesting news, and that’s an abundance of ants. This week, the latest ant census came out. Who knew there was one, right? 20 quadrillion ants on the planet Earth, how do you wrap your head around that number?

KATHERINE WU: I honestly can’t. I can barely picture a couple hundred ants, which is a really great point that Sabrina Imbler made at Defector this week. That is a trillion ants multiplied by 20,000. I can’t do that kind of math in a way that allows me to picture a pile of 20 quadrillion ants. But that is so cool, right? That means there’s 2.5 million ants for every single one of us humans here on Earth. And if you sort of weighed all that, it would be 12 megatons of carbon, which would outweigh all of the wild birds and mammals on Earth put together.

IRA FLATOW: And how do you find out how many ants there are?

KATHERINE WU: Well, Ira, you count them one by one by one. I’m joking.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] I was going to say–

KATHERINE WU: But that is– [LAUGHS]

IRA FLATOW: I’d hate to be that grad student.

KATHERINE WU: That is part of the answer, though, right? It’s kind of like how we do the census in the US. You go to a certain part of the world or the country, depending on the scope of your census. You count how many individuals are there. And you sort of extrapolate out.

So the people who did this study just compiled a ton of data from many, many, many studies that have been done over decades, looking at different countries, different geographies, different types of ecosystems, trying to get a sense of the density of ants in different parts of the world and extrapolating out. And what I think is actually amazing is that that 20 quadrillion estimate, they call it a conservative estimate. So there could be way more ants that we’re dealing with that we just haven’t seen yet.

IRA FLATOW: Wow, we always talk about how many termites there are, and we know there are a lot of termites. But we never think about how many ants there are, and we need to pay a little more attention, a little more respect then.

KATHERINE WU: Oh, I think so. Ants are amazing. They can do so many things we can’t, and if they outnumber us by this much, they definitely deserve our respect.

IRA FLATOW: Speaking of abundance, it turns out– now, this is a great segue– that Mars, the Mars Rover Perseverance, has a pretty sizable rock collection and some potentially very important ones, right?

KATHERINE WU: Yeah, so this rover has been hanging out on Mars for a little while now, collecting rocks slowly from all over the crater in which it landed, and what is pretty cool is this crater, Jezero Crater, there used to be water in it billions of years ago. And so if Perseverance is doing its job, it’s going to be collecting these rocks. The hope is that those rocks will make it back to Earth sometime in the next decade or so, and scientists here will be able to study them and get a sense of what was going on in that lake, what was going on before the lake arrived. Was there even life there, at some point, that deposited little chemical signatures that we can pull out in the present?

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, because scientists were saying that’s a very important place. That’s probably one of the most important places that Perseverance has visited.

KATHERINE WU: Absolutely.

IRA FLATOW: And here’s the question. How do we plan to get the rocks back to Earth, then, to analyze how important it is?

KATHERINE WU: It’s a great question, and luckily, the Rover will not have to do that job. It’s already been working very, very hard. But we’re going to be launching two spacecrafts in 2027 and 2028, whose specific jobs will be to grab those samples and bring them back to us. Think of them as the freight trucks going between Earth and Mars.

IRA FLATOW: Well, if you’re saying we’re going to launch them in 2027 or 2028, they’ve got to go there. They’ve got to take a while to get there, get the rocks, and then bring them back. So we’re talking, what, 10 years.

KATHERINE WU: The goal is 2033 to have them back here on Earth.

IRA FLATOW: Wow. Well, it has been a big week on Mars, especially for NASA listening in on what’s going on there because NASA’s released audio of a meteoroid hitting Mars recorded by its Rover Insight. Let’s listen to that.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

[BUBBLING]

[PLAYBACK ENDS]

I swear that sounds like water dropping.

KATHERINE WU: I was going to say. It’s like that was a soap bubble, maybe popping.

[LAUGHTER]

IRA FLATOW: All right, OK, so cool sound. But can we learn anything from it?

KATHERINE WU: Yeah, so that was not a soap bubble. Those were space rocks crashing into Mars. This is the first time that Insight has conclusively picked up those sounds and that scientists have really analyzed them and been able to say, wow, that’s the sound of something from outer space impacting the surface of Mars and creating craters. These were impacts that happened while the pandemic was raging here on Earth in 2020 and 2021. And the great thing is, if we start to understand what happens when rocks impact the surface of Mars, that gives us some, well, insight, haha–

IRA FLATOW: Hmm.

KATHERINE WU: –into what happened with all those craters that are all over Mars that happened in the past. You can think of craters as a fossil record, almost, for the surface of a planet. And the Martian surface is especially susceptible to these kinds of impacts. It’s pretty near the asteroid belt. The atmosphere is thin. And so if we get a better understanding of all those craters, we’re basically reading Mars’ history book.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, well, that sound collected on Mars is something we won’t have to wait 10 years to analyze.

KATHERINE WU: Definitely. We’re just eavesdropping.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you, Katie, for taking time to be with us today.

KATHERINE WU: Thanks so much for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Katherine Wu, staff writer at The Atlantic. She is based in New Haven, Connecticut.

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.