Can The Great Lakes Stay Great?

34:39 minutes

Want to dive deeper into the science of the Great Lakes? Read ‘The Death and Life of the Great Lakes’ with the SciFri Book Club!

The Great Lakes have come a long way since the Clean Water Act passed in 1972. Tributaries no longer catch on fire. Residents of Chicago and Cleveland visit the beach with (usually) less trepidation.

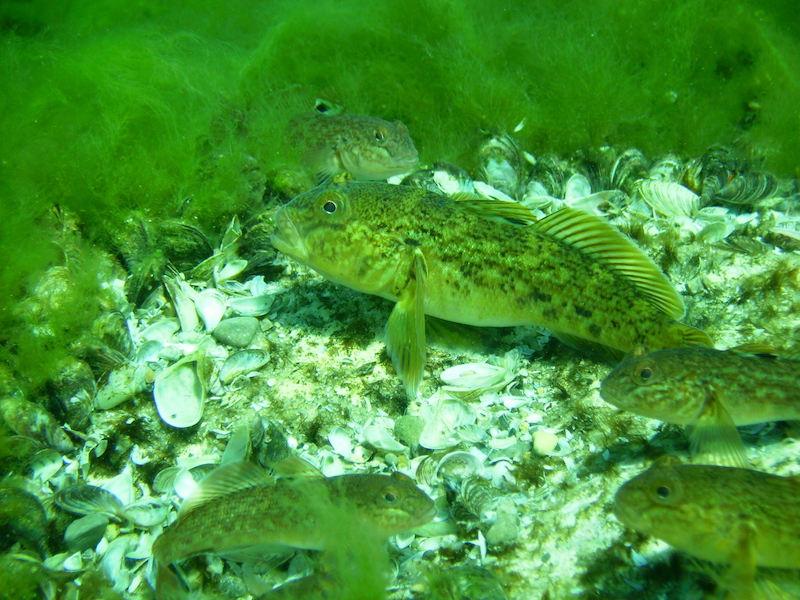

But all’s not well. Unusually clear waters signal a damaged, nutrient-poor ecosystem. In northern Lake Michigan, avian botulism is killing thousands of birds every year. In 2014, residents of Toledo, Ohio, couldn’t drink their tap water—drawn from Lake Erie—for days because of toxins released by hazardous algae. And in all the lakes, invasive zebra and quagga mussels are reengineering the food webs, challenging the survival of sports fishermen’s salmon and native trout alike.

Milwaukee journalist Dan Egan, author of The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, joins ecologists Harvey Bootsma of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Donna Kashian of Wayne State University for a conversation about the evolution of the lakes and the challenges they’ve faced in the last four decades, and how they can persist as as a sustainable ecosystem and source of potable water for generations to come. Read an excerpt about how lake fish are coping with pollution from Egan’s book.

Plus, Great Lakes Today reporter Elizabeth Miller explains the potential harm of a federal budget proposal to strip more than $300 million from Great Lakes restoration projects and related efforts to improve and understand the lakes.

Dan Egan is the author of The Devil’s Element, and Journalist in Residence in the School of Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Donna Kashian is a professor of Biological Sciences at Wayne State University in Detroit, Michigan.

Harvey Bootsma is an associate professor in Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Elizabeth Miller is a reporter and producer at Great Lakes Today. She’s based in Cleveland, Ohio.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. Pop quiz time. Can you name all five of the Great Lakes? Not hard if you live on one of the Great Lakes. You have that helpful acronym HOMES– Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie and Superior. As I say, if you live there, you know what it is. And just like you know the Lakes have been going through some tough times over the last 100 years– from the spread of parasite sea lampreys in the 30s, to pollution so bad you couldn’t swim in Lake Erie in the 70s, to the arrival of the invasive zebra, and quagga mussels at the end of the last century.

And as the climate continues to warm we want to know what else so the Lakes. After all collectively they make up one fifth of all the freshwater on the planet. And some 40 million people rely on them for drinking water, plus the fishing, the recreational boating, and of course their shipping. And if you’ve ever stood on the edge of one on a clear summer day, you know there’s something a bit magical about how big they are. You can’t see the edge.

Do you live near the Great Lakes? Have you ever noticed them changing over the years? We’d like to know about it. Give us a call. 844-724-8255. 844-sci-talk. Of course, you can tweet us @scifri. So we’re going to talk about the challenges ahead for the Great Lakes. So let me introduce my guests. Dan Egan, a reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and Senior Water Policy fellow at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. He’s also the author of a really good new book, The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, out from Norton this spring. Welcome to Science Friday.

DAN EGAN: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome. Harvey Bootsma, Associate Professor of Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. Welcome to Science Friday.

HARVEY BOOTSMA: Thanks. It’s great to be here.

IRA FLATOW: And Donna Kashian, Associate Professor of Aquatic Ecology at Wayne State University, and a visiting scientist at Noah’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Lab. And she is based in Brighton, Michigan. Welcome to Science Friday.

DONNA KASHIAN: Thank you for having me.

IRA FLATOW: Dan let me begin with you because your book is titled The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, does that mean there’s nothing to worry about in 2017?

DAN EGAN: I would say absolutely not. But yeah, that title is in a way it’s a nod to Jane Jacob’s, Death and Life of the Great American Cities, but obviously the Great Lakes aren’t dead. But in a way they aren’t what they were 100 years ago. They’re in many ways completely different. So there is a new type of life going on out there, and that was the rationale for the title.

IRA FLATOW: Give me what you would consider the biggest problem? Name just one for me.

DAN EGAN: Invasive species, and specifically, I would say quagga mussels.

IRA FLATOW: Why?

DAN EGAN: Because the quagga mussels have just fundamentally rewired the way energy flows through the lakes. They are the dominant organism out there, and they make their living by filtering plankton out of the water. And so they’ve basically taken out the bottom of the food chain, and obviously everything above that is suffering.

IRA FLATOW: Donna Kashian, a lot of people just fly over the Great Lakes a lot, and they see it from an airplane. Tell the rest of us what’s so wonderful about having the Great Lakes here.

DONNA KASHIAN: Well, one is that it’s the fifth of the freshwater available to the world. That’s kind of the big basic one. But it’s the recreational value that comes with it. The commercial value that comes with it. And what it means to the people who live in the region for recreation and all those things. It’s very important for all those reasons.

IRA FLATOW: Dan, you agree?

DAN EGAN: Oh, yeah absolutely. They define the region culturally, to a large degree economically, and I mean anybody who lives here knows that these are the things that make the Great Lakes region so great.

IRA FLATOW: Let me ask Harvey Bootsma to tell us– we were talking about the mussels changing the Great Lakes ecosystem. Can we say that it’s all bad news? There’s got to be some good news in the Lakes.

HARVEY BOOTSMA: Yeah, I guess it depends what you value. If you like really nice, clear water then mussels aren’t necessarily a bad thing. They’re great filtering machines, and they filter all the particles out of the water. And as a result, many of the Great Lakes now are much clearer than they have been in the past. So if that’s your only management goal then you might think that they’re a good thing. But as Dan pointed out, there are quite a few negative aspects associated with the mussels as well. But I should point out that we have had a number of challenges in the past with regard to the Great Lakes. And while it’s easy to focus on the problems and challenges we have, I think it’s also important to remember that we have had success stories in the past as well managing some of the challenges that have arisen over the years.

IRA FLATOW: Donna, we’re now seeing big algae blooms in the Lakes too. What kind of damage on these blooms doing?

DONNA KASHIAN: Well, the damage has got multiple aspects to it too. One, is the environmental impacts, which for a lot of these we’re still not fully aware of what they’re causing in terms of impacts on fisheries and native species. And then there’s the economic impacts that come with the recreational anglers and the commercial anglers going out and avoiding the blooms. Or not going fishing in those areas. And then there’s the potential threats to human health, and a lot of people are aware that Toledo water was shut down not too long ago in some other local areas because of the toxins in the water. So then you have entire cities and populations can no longer use the water. And it’s a little bit more serious in some ways than bacterial contamination because you can’t boil the water to get rid of the toxins. So then the people are really left without water in their homes and water to use in restaurants. And it’s pretty serious impacts.

IRA FLATOW: Harvey, I mean these are five very large bodies of water. I mean we’re making statements that cover all five Great Lakes. I mean can something be holding true for all of them?

HARVEY BOOTSMA: There are some generalizations. But for example, when we talk about the impact of quagga mussels, which is one of the largest impacts we’re looking at right now. That’s confined primarily to the lower Great Lakes, Michigan, Huron, Ontario, and Erie. There are mussels in Lake Superior, but they don’t, at least so far, they haven’t been able to do very well there– partly because it’s colder there, and partly because the chemistry of Lake Superior is such that mussels have a hard time forming shells there.

IRA FLATOW: Lots of people want to get in on this. Our number 844-724-8255. Let me go to some tweets that have come in. Let me go to Michelle who says, “I lived in Chicago my whole life, and I can swear that Lake Michigan is getting a brighter blue hue every summer.” Anybody?

DAN EGAN: Well, yeah, it is. I mean the Lake looks spectacular from the surface, but you know it really belies the chaos that’s going on underneath. As Harvey said earlier, clear water doesn’t necessarily mean clean water. And I’ll give you a real quick example, and Harvey jump in if I botch something here. But here’s an example of how this biological pollution can be just as problematic as anything coming out of a pipe or a smokestack. The mussels have so cleared the water on Lake Michigan that it’s allowed for a type of algae to just explode because that algae needs three things. It needs sunlight, it needs a hard surface, and it needs food. And the mussels provide all three by clearing up the water, by providing the surface with their shells, and then by feeding it with their excrement. So then this algae dies off and it creates vast swaths of oxygen deprived areas, and that allows a botulism bacteria to thrive. The mussels suck up this botulism bacteria. This is how the theory goes. And then another invasive species, a little fish about the size of your thumb called the round goby, eats these mussels. And then the mussels are carrying the botulism, the fish get botulism, they die, they float to the surface, and then they get eaten by birds. And birds are dying by the tens of thousands on the western– or I guess would be the eastern– shore of Lake Michigan. It’s pretty frightening.

HARVEY BOOTSMA: And I might add to that too. I think that highlights one of the challenges we face with managing the Great Lakes in that if you simply look at them from the outside to many people the lakes is a flat surface of water. And if you just look at it that way it doesn’t seem like there’s a lot of problems with the lakes. And the real problem is our under the surface, and that’s the thing that most people don’t see. The Lakes have changed dramatically over the last 10 years. And most people are unaware of that because they see the lake as a flat surface. And I often make the analogy between lakes and say a terrestrial national park where say if you lost the bison from Yellowstone National Park a lot of people would be very upset about that because it’s a very visible thing. We’ve had changes in lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes that are just as drastic as that, but haven’t raised the alarm as much because many people just don’t see those changes.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Grand Haven, Michigan. To Brody, hi, welcome.

CALLER: Hi, there. Thanks for taking my call. I was wondering if someone from the panel could comment on the DNR feeding the chinook salmon in Lake Michigan. And how their plan to stop feeding that program is going to affect the potential alewives situation in the lakes, and where the flow of energy is going to go from there.

DAN EGAN: I can jump in on this.

IRA FLATOW: Explain what he’s talking about.

DAN EGAN: OK. The DNR is the Department of Natural Resources. And there are four states bordering Lake Michigan and they cooperatively manage the fishery. And since the first wave of invasive species arrived the lakes have been heavily managed. Pacific salmon were brought in the 1960s to get control of an exploding alewife population. And that’s an east coast herring that made its way into the Lakes through those shipping channels that we punched out to the Atlantic beginning in the early 1800s.

So for the last 50 years or so, we’ve had a tremendous salmon fishery on the Great Lakes. The problem today is as we were talking earlier these mussels have so knocked out the bottom of the food chain that the alewives are starting to disappear. And as go the alewives so go the salmon. And so there’s a big debate right now about how many salmon these states should be planting in the lake annually. Because they do drive– the Great Lakes have a $7 billion dollar fishery. Most of that is recreational. So there’s a big debate about how much the hand of humans should be playing in this with all these changes going under way.

IRA FLATOW: Do you agree Donna?

DONNA KASHIAN: Yeah I’m not really familiar with the seining– the political aspect of it, and the program. But yes, he’s exactly right. And it’s the collapse of all the other things that come in with it.

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to Sean in Dayton. Hi Sean. Welcome.

CALLER: Thank you. Yeah I have had the benefit of going to a family island up in Lake Huron off Georgian Bay for the last 25 years. And we’ve seen the water level drop considerably over that time. And I’ve read a lot of reasons for it, but one of the most interesting things I’ve read about and wondered if you could talk a little bit about is the idea of glacial rebounding as the Earth’s crust has been bouncing back from the weight of the glaciers receding after the Ice Age.

IRA FLATOW: OK. Anybody know about that?

DONNA KASHIAN: I can touch on that. So the glacial rebound is a phenomenon that you’re absolutely correct that after the weight of the glaciers have left the state the land is coming back out. This process is occurring incredibly slow in terms of our timeline and human presence on earth. So the lake levels are not what you see is the lake levels from year to year. And the changes in those are not necessarily related to that at all. Those are going to be more due to things like changes in the water the evaporation rates over winter if we lose more ice. There are going to be more evaporation rates. So we’re going to have higher losses. And so you can have water lower levels there. So you’ve got a lot of climate factors, including rainfall and stuff like that that play a role in it. But glacial rebound and the rate at which it happens, and I forgot what the exact amount is, it is actually quite small on a year to year basis. So we couldn’t blame that on the fluctuations in annual changes in the water levels.

IRA FLATOW: And we have a tweet from Susan who says, “Please speak about the water level crisis on Lake Ontario. Our shorelines are devastated. Thoughts on plan 2014?”

DAN EGAN: OK. Well, I’ll just talk a little bit about lake levels. And Ontario, Lake Ontario, is a long way from the western shore of Lake Michigan where Harvey and I are today. But Lake Ontario is at a record high right now. And what’s been going on is on Lakes Michigan and Huron for 13 or 14 years they were well below their long term average. And the theory behind this is you think that the lakes would be pretty immune to climate change because they’re so vast, and there’s so much inertia built into the system. But they’re actually turning out to be quite vulnerable because as the winter’s warm ever so subtly we’re not getting the ice cover that we have historically.

So instead of having all this solar radiation bounced back up into the heavens during the middle of the winter and into the spring, the open water starts sucking up heat. And that means that by the time late summer comes the lakes are warmer than they’ve been historically. And then when you know the gales of November come blowing in with their cold winds, that temperature differential creates massive evaporation, and the lakes literally get sucked into the sky. So the problem was low water just until about two years ago. And then something– about three years ago– then the polar vortex kicked in, which is something nobody was predicting. Nobody I knew was predicting. And especially predicting the impact it would have on the lakes it brought exceptional ice cover and the lakes rebounded fast. And that’s what we’re experiencing even to this day. And it’s been a wet spring too.

IRA FLATOW: I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International, talking about the various aspects of the Great Lakes and welcoming your calls. 844-724-8255. You can also reach us at scifri, S-C-I-F-R-I. Lots of people wanting to ask about the Great Lakes. Let’s go to a couple of more phone calls here. Let’s go to Kenneth in Janesville, Wisconsin. Hi Kenneth.

CALLER: Hello.

IRA FLATOW: Hi there.

CALLER: I wondered about dealing with the mollusks overpopulation and what the process for dealing with them.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. OK. Are they edible? Could you could you make escargot out of them?

HARVEY BOOTSMA: Unfortunately, there is no simple answers to that challenge. They’re probably not edible. There may be concerns about contaminant concentrations in them because they’re filter feeders. Although, there may be other prospects. I have half jokingly suggested to people that maybe they could be harvested for fertilizer, or pet food, or something like that. But as far as reducing their numbers in the Great Lakes go, there are really no management options to do that. There are options if you’re dealing with smaller lakes or reservoirs. There are certain types of treatments that you can apply that will really reduce mussel numbers or in some cases even eliminate them. But if mussels disappear from the Great Lakes it’s not going to be because anything we do. It’s going to be because of some other natural or biological process happening to the system– either a parasite, or some disease, or some other predator that comes in and eats lots of them.

IRA FLATOW: All right. I’m going to take a break and we’ll come back and talk more about the Great Lakes. But we’re also talking about the president’s skinny budget. What that means? Major programs being cut aimed at cleaning up the Great Lakes. We’ll check on how big the impact could be. Plus more on the future of these vast ecosystems. 844-724-8255. Tweet @scifri. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’ve been talking about the challenges behind and ahead for the Great Lakes– from invasive species to climate change. But there is another one we haven’t touched on, and that is money. The Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funds more than $300 million worth of projects to restore fish habitat, cleanup pollution, and otherwise improve the lakes. And in the federal skinny budget the White House released this spring, most of that budget would be eliminated. Add that to other agency cuts and the Great Lakes could lose many of the projects aimed at keeping them usable. Here to explain the money is Elizabeth Miller, a reporter and producer for Great Lakes Today, based in Cleveland. Welcome to Science Friday.

ELIZABETH MILLER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: What is the extent of the proposed cuts? So as you said, the GLRI funds Great Lakes Restoration projects gives $300 million annually. And so Trump’s skinny budget completely slashes that to zero. And in addition to that, it looks like we’ll be losing grants, and education programs through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Superfund Site Cleanup, and cuts to the Department of Agriculture, which could mean lots of subsidies for new farming practices– things like cover crops that reduce nutrient runoff.

IRA FLATOW: And so how vital are these projects to the continued or improved health of the Great Lakes?

ELIZABETH MILLER: Well, a lot of these projects– what the federal money does is that it leverages state and local money to go towards these projects. And so having that pot of money that groups can ask for and can submit proposals for really helps out a lot of these restoration projects. And over 2,000 projects have received funding from the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative since 2010.

IRA FLATOW: Hmm. Canada also borders on the Great Lakes we know. Could cuts to restoration efforts affect international relationships?

ELIZABETH MILLER: Yes, completely. And there’s a lot of different plans that really relate to the US and Canada. I mean this is a bi-national body of water. And so what we’re doing is being watched very closely by Canada. And they’re just as concerned as some of the environmental organizations that I’ve spoken to here on the US side of the Great Lakes.

IRA FLATOW: You know this is just very puzzling because it’s counter intuitive for we observers outside of the region. Because we know that Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio these are the very key states that the Trump administration depended on for support in winning the election. And yet now, they’re proposing to cut the money to keep their lakes healthy.

ELIZABETH MILLER: Yeah, and what’s really interesting about this Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, and all of these different cuts proposed related to the Great Lakes, is that they’re a very bipartisan issue. We’ve got politicians on every side of the aisle– Republicans, Democrats, Independents. Everyone has pledged to fight this cut. And just yesterday actually two representatives from Ohio, Dave Joyce and Marcy Kaptur, questioned the new EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt, asking, “Are you going to take care of our Great Lakes? Are you going to help get this funding back to $300 million?” And he says he recognizes the importance of the Great Lakes.

IRA FLATOW: But no commitment.

ELIZABETH MILLER: No commitment. And Marcy Kaptur, a representative from Ohio here, actually invited him to tour the Great Lakes, which he accepted. So maybe that will change his mind.

IRA FLATOW: Well, she’s taking a chance by inviting the person who won’t give them any money.

ELIZABETH MILLER: Yeah. And I think what she wants to show is that change that’s happened over the last six years especially with this Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, is a lot of these projects wouldn’t get done wouldn’t get funded at all without the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

IRA FLATOW: It’s baffling. It just sounds like politically you’re just shooting yourself in the foot. But you know, what do I know? All I remember from the 60s the Lakes catching on fire, and the environmental movement happening. And they were sort of the instigators of the environmental movement.

ELIZABETH MILLER: Yeah. It’s actually the anniversary of the Cuyahoga River catching fire next week. And I know there are some local organizations that are really proud of how far that the river’s come.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you very much Elizabeth for taking time to talk with us today.

ELIZABETH MILLER: Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And good luck. Elizabeth Miller is a reporter for Great Lakes Today in Cleveland. We’re also talking about the Great Lakes and our number again if you’d like to 844-724-8255. You can also tweet us @scifri. Talking with Dan Egan, Harvey Bootsma, and Donna Kashian. Any reaction to that? Let me ask you Dan. What do you think? How do you square this circle?

DAN EGAN: Well, we don’t want to go backwards, and it seems that we are. The Cuyahoga River fire was famous because you know it really did mark the beginning of the end for an industry to just dump what they wanted in the lakes. But what was really important about that fire wasn’t that the river caught fire it was it was last time the river caught fire. It had burned from the 1800s forward. And for some reason people tolerated it for 100 years or so. And then for some reason they just decided enough is enough. And we had a Cuyahoga like moment just in 2014, also on Lake Erie, and it it really kind of shows the state of the Lakes and the direction we could be headed due to a number of problems. And I’ll just talk real quickly about what happened in Toledo.

OK. So when we talk about these mussels, you can’t eat them. They’re really small. But the important thing is not to look at them as individuals, but just as you know the mass that they are. As Harvey once explained to me, I could walk from Milwaukee 80 miles across Lake Michigan to Muskegon on a bed of quagga mussels. That density’s up to 100,000 per square meter. And that’s because they cluster on top of each other, and create this kind of gnarled coral like stuff. And they filter everything out of the water. It’s a similar situation on Lake Erie. And what’s happened over there in the Western basin is that three things have just kind of come together. There’s a muscle infestation, there’s overapplication of fertilizer on the croplands, specifically the corn fields west of Lake Erie, and with climate change we’re getting bigger spring storms.

So we get these big pulses of rain and they wash the fertilizer into the water. And in the 1960s that fertilizer might have spawned algae outbreaks and assemblage of a bunch of different types of algae. But these mussels, these brainless mussels, are just smart enough to not eat a certain type of toxic algae on Lake Erie. So they’ve selected for this toxic algae called microcystis. And so when you get an algae bloom today, it’s more likely to be this toxic stuff. You can see it on YouTube– mussels sucking everything out of the water, but spitting back these flecks. And these flecks are toxic algae.

So those blooms happen, and in the summer of 2014, one of them went right into the Toledo drinking water intake, and knocked out the drinking water source for almost a half a million people. And you couldn’t just boil it out. It wasn’t like a standard boil order until we get the system fixed. If you boiled it you would concentrate the toxin. So you’ve got a city of like a half a million people and they can’t drink their water. And even in the dark days of the Cuyahoga River burning, the lake was never so bad that you couldn’t treat it to drinking water standards. So going backwards at this time and eliminating this Great Lakes Restoration Initiative threatens programs under way to get a handle on these toxic algae blooms. And I don’t see how that will hold any popular support. And you’ve got to remember this budget is just it’s the administration’s first crack. Congress is the one that set it– the members will set it. And as it’s been said these are not partisan issues. Clean water-

IRA FLATOW: You think that eventually that money will come back? It’s just too political a risk.

DAN EGAN: I’m confidant it will to some degree, but I’m not privy to any.

HARVEY BOOTSMA: And Ira, if I could just add a bit to what Dan said regarding your question about whether it’s worth putting funding into the Great Lakes. When you evaluate ecosystem services it’s more challenging than evaluating say the profitability of a certain business. We get huge benefits from the Great Lakes. And there’s been a number of economic assessments done on the Great Lakes. All of which show that money invested in the Great Lakes produces a return on investment anywhere from two fold to fivefold.

The challenge is that in many cases it’s difficult for people to see or realize the benefits that we get from the Great Lakes. The number of $7 billion per year for the sport fishery is commonly cited, and that’s true. But there’s other huge benefits that we get from the Great Lakes that are easy to overlook. The simple fact that Great Lakes are amazing water purification systems. And the quality of water that we get from Great Lakes for municipal supply for drinking and other uses is a huge benefit that we get from the lakes that most people don’t value. They don’t put a number on that. And so I think that’s part of the challenge here is getting policymakers and managers to realize the value of these systems. It’s the classic case of you don’t know what you have until it’s gone. And if we don’t manage the systems we will realize how important they are.

IRA FLATOW: It brings it full circle on that song. Let me see. We have a lot of tweets that have come in. Let me see if I can cycle through a few of them here. Doug writes, “Hey scifri. All this talk of invasive species and no mention of Asian carp. Where does that stand?

HARVEY BOOTSMA: Well, fortunately, as far as we know Asian carp are not in Lake Michigan yet. They’re knocking at the door. They’re coming up the Mississippi River in the Illinois river system. There have been some signs that maybe they’re in the system. People have sampled for what’s called environmental DNA, which tells you if a species might be in the water. And that has occasionally provided positive hits that says they might be there. But no one has caught one yet. So the best we can do right now is based on what we know about both the lakes and the Asian carp is try to predict what will happen. And that has been done by researchers at the Noah Great Lakes Lab in Ann Arbor, and also at Michigan State University. And their forecasts suggest that the impact would be relatively modest in Lake Michigan, partly because quagga mussels have beat them to the punch. The Asian carp are filter feeders. They feed on plankton. But there’s just not a lot of that left in Lake Michigan because quagga mussels have eaten a lot of that. They would do better in Lake Erie because there’s more plankton for them to feed on Lake Erie.

IRA FLATOW: Donna Kashian, let me ask you a question about pollution. You know we have seen in recent weeks, there’s this island in the Pacific with all this plastic that has washed up on it. Are there beaches in the Great Lakes with plastic that is washing up? Or other pharmaceuticals or things like that in the water now?

DONNA KASHIAN: Yeah. If you go to any beach in the Great Lakes and any beach anywhere you find little plastic pieces everywhere. And those are the ones you can see. There’s also the microbead plastics that we’ve recently had a ban on. And the micro beads are the plastics that are found in the products for the scrubs for washing your face and stuff like that. And I think that’s a wonderful example of us being proactive in actually anticipating that these could cause an environmental impact. And they have been banned in the Great Lakes, and that’s a wonderful thing.

Normally, we are a very reactive society. We wait until everything is dying or some river’s on fire, and then we start initiating changes in policy. And that’s a really good example of something that we did and made a change before it became more of a problem. In terms of the other things like pharmaceuticals, we don’t know what impact this is going to have. There is no doubt if you go out and take a water sample from almost any water body surface water, that you are going to have on an amount of pharmaceuticals in it. They come from agricultural products, they come from wastewater from humans. They’re made to be biologically active, and they pass through and end up in the wastewater.

And right now, there are currently no regulations on them in the water. And we don’t know the effects. But we know whenever you have water we are now consuming pharmaceuticals and other contaminants– personal care products when we do so. So there’s a lot to be done on that and understanding. We’ve seen feminization of fish from some chemicals that are known to disrupt endocrine disruption. And so what are the impacts on humans? We can’t do human testing, so we really don’t know yet. So we need more research and more understanding on these. And if possible, if we need to enact some kind of control or treatment to our drinking water that will eliminate these. But right now we don’t have enough information.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from PRI, Public Radio International. Sorry to have to jump in there on you. I’m Ira Flatow talking about the Great Lakes. Just a few more minutes and lots of tweets. So let me go to, for our nutrients writes, “It’s not over application of fertilizer. It’s fertilizer applied at the wrong time and place.” Anybody want to comment on that?

DAN EGAN: Well, yeah I mean that is a problem. But back in the 1960s, when the Cuyahoga River was burning and Lake Erie was declared by some national publications as dead, it really wasn’t. But it did have these massive areas of oxygen depleted water because of all the algae blooms. And then when they would die they would burn up the oxygen. We solved that problem by basically– talking about Lake Erie right now– by putting it on a phosphorus diet. And they dramatically cut the loading going into the lake, and as predicted the lake recovered really quickly. From 1971 to 1985 the change was just dramatic. Well, we’re back to these massive dead zones again. And the problem isn’t that any more phosphorus is going into the lake than there was once the lake was declared recovered. It’s that it’s coming off croplands in a very potent form. It’s called dissolved reactive phosphorus, and it’s just like gasoline in terms of algae bloom explosions.

So once again we have a prescription. They want to cut the loading by 40%, and you know the scientists were right back in the 60s and 70s. And there’s every reason to believe that they’d be right today, and that we can fix this problem. But so far, we haven’t had the political will to do so.

IRA FLATOW: One last quick question from Andrea who tweets, “Can you discuss attempts to pump Great Lake water to other states? Ramifications of doing this?”

DONNA KASHIAN: So this has been-

IRA FLATOW: Go ahead.

DONNA KASHIAN: So this has been an issue that has come to the forefront recently, and those sitting in Wisconsin are even closer to it. But yes, so there is now water withdrawals happening– not only being pumped out, but also companies like Nestle withdrawing water for bottling purposes. And this is something these Great Lakes don’t just belong to the United States they belong to Canada too and we got to be really careful about that. Because once we have made it legal to pump water as countries further west need water there is going to be more and more pressure to justify for human sustainability to have water moved out of the Great Lakes. And we have to be very careful. It’s a slippery slope, and we have to be very protective of the water to maintain the resource. Because the more pressure and removal the more impact on the system we’re going to see.

IRA FLATOW: Now, I want to thank you all. I mean I’m glad we took time to talk about this because this is such an important issue. And it gets so little coverage that we see on all the coasts. So I want to thank all of my guests– Dan Egan, reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Senior Water Policy fellow, University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, and you can read an excerpt of his book sciencefriday.com/lakes. It’s a great book The Death and Life of the Great Lakes. Donna Kashian is an associate professor of Aquatic Ecology at Wayne State University in Brighton, Michigan, and Harvey Bootsma is associate professor of Freshwater Sciences at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee. Thank you all for taking time to be with us today.

HARVEY BOOTSMA: Thanks for having us.

IRA FLATOW: You’re welcome.

Christie Taylor was a producer for Science Friday. Her days involved diligent research, too many phone calls for an introvert, and asking scientists if they have any audio of that narwhal heartbeat.