Welcome To One Of The Deadliest Labs In The World

17:37 minutes

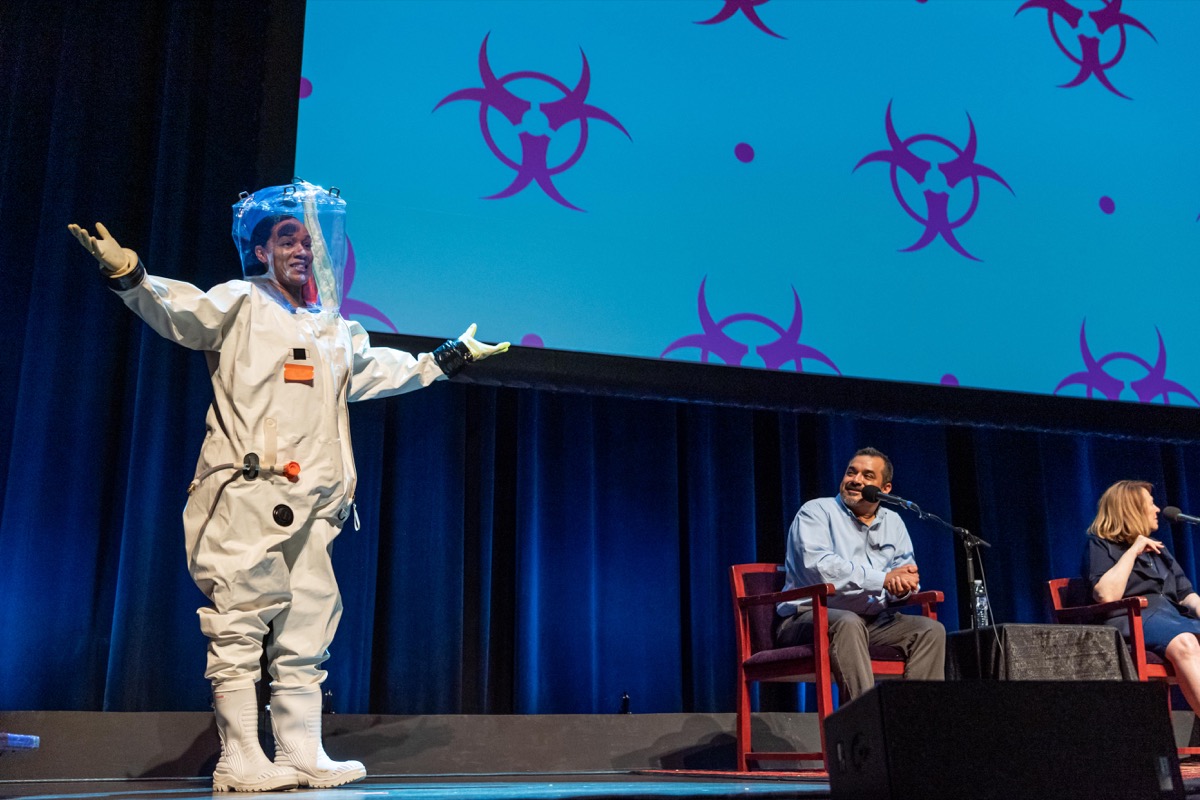

Imagine stepping into a white suit, pulling on thick rubber gloves and a helmet with a clear face plate. You can only talk to your colleagues through an earpiece, and a rubber hose supplies you with breathable air. Sounds like something you wear in space, right?

In this case, you’re not an astronaut. You’re working in a biosafety level 4 research lab, the only place where the most dangerous pathogens—the ones with no known cures—can be studied in a lab setting.

For example, the latest outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has killed over 1,800 people since last August. And while that outbreak is happening half a world away, the virus is also inside the Texas Biomedical Research Institute, a biosafety level 4 lab in San Antonio, where scientists are looking for a cure.

Dr. Jean Patterson, a professor there, and Dr. Ricardo Carrion, professor and director of maximum containment contract research, join Ira live on stage in San Antonio, Texas for a safe peek inside the place where the world’s most dangerous diseases are studied.

Check out what the lab looks like—and what they study.

Jean Patterson is a professor at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

Ricardo Carrion is a professor and director of maximum containment contract research at the Texas Biomedical Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow, coming to you from the Tobin Center for the Performing Arts in San Antonio, Texas.

[APPLAUSE]

Imagine stepping into a white suit, pulling on thick rubber gloves and a helmet with a clear face plate. And you can only talk to your colleagues through an earpiece. And a rubber hose supplies you with breathable air. Sounds like a spacesuit, right? Nope. In this case, you’re not an astronaut. You’re working in a biosafety lab of the highest level.

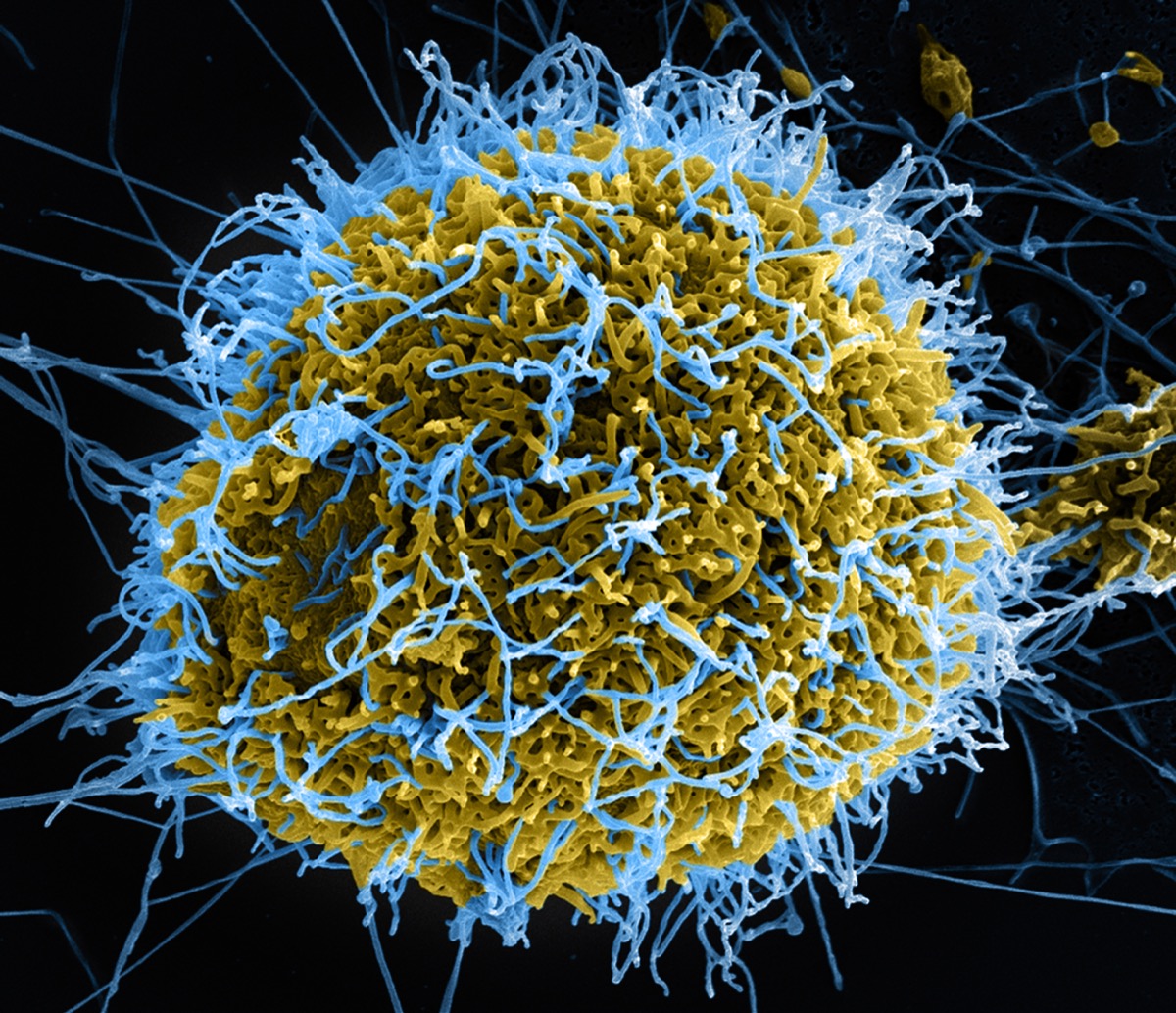

And that means level 4, the only place where the most dangerous pathogens, the ones with no known cures, can be studied. For example, the latest outbreak of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has killed over 1,800 people since last August.

And while that outbreak is happening half a world away, the virus is also here in San Antonio. Did you know that? It’s locked up very safely in a biosafety level 4 lab here, where scientists are looking for a cure. And joining me now for a safe peek inside the place where the world’s most dangerous diseases are studied are my next guests, Dr. Jean Patterson, professor at Texas Biomedical Research Institute. Welcome.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Ricardo Carrion, professor and director of maximum containment contract research at Texas Biomedical Research Institute. Welcome, both of you.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Carrion, first of all, describe what is a level 4 containment.

RICARDO CARRION: Level 4 laboratory is a laboratory that’s specially designed to allow us to work with these pathogens that Ira mentioned. So right now up in the screen, you see an individual wearing a spacesuit essentially. It’s a onepiece vinyl suit that has no penetrations except for a single entry point for an air hose.

So the individuals work in a laboratory that’s under extreme negative pressure. So you’re thinking you’re in a bubble that’s full of air, and you’re in a negative environment, so air is being forced out of that room. So if you get a hole in your suit, there’s really no way for a virus or anything to enter because everything’s being forced out of the suit into a room and then passed out through air filters.

And there’s an image. You see individuals working with microscopes, but there’s these yellow hoses that attach to their suits that supply them breathing air. Once you work in the laboratory, you have to decontaminate the suit. On the way out, they’re required to take a chemical shower. So the suit itself, they stand in a large chamber that has a disinfection solution. And they stand in that chamber for about eight minutes where they go through a disinfection cycle and rinse cycle.

And they walk out of the laboratory, and they’re able to then hang their suits up, let them air dry, and they themselves take a physical shower. So the idea being is that if perchance you were to get the virus on your skin, you then wash it off with a shower. Now all the waste in that laboratory produced gets autoclaved. So that’s cooked under extreme pressure and heat before it gets discharged. So everything in that laboratory is disinfected, so there’s no way to actually transmit the virus outside the lab and to our sewer systems.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Patterson, there are only a few biosafety labs like this around in the country. How was San Antonio fortunate enough to land one here?

JEAN PATTERSON: Well, why not San Antonio?

[APPLAUSE]

Before we built this lab, which– we went hot in March of 2000, we had a glove box, the old fashioned glove box where we just stick your hands in, and that was to work on herpes B virus. Herpes B is a virus that’s carried by monkeys, and it’s relatively benign to monkeys, but can be almost uniformly fatal to humans. And that’s the definition of a level 4. It’s potentially lethal. There’s no treatment, no vaccines, and can be transmitted in the laboratory.

So we had this program for Herpes B, which all of the national primate centers and Texas Biomedicine National Primate Center relied on us to tell us if anybody may have been exposed or infected with Herpes B. So when we built this new lab, we decided we would go to a full suit lab, just assuming that it might be necessary to do different kinds of experiments.

And so we built it. And then, of course, after 9/11 and the anthrax attacks, there was a great deal more interest in biological weapons. And so we quickly converted the laboratory to using animals, as well as working with hemorrhagic fevers.

IRA FLATOW: And so when did Ebola become one of the main things that you guys study?

JEAN PATTERSON: 2003 is when we had our first–

IRA FLATOW: Because– what was the catalyst to that?

JEAN PATTERSON: Well, the government made a list of things they called select agents. And these are things that the government has predetermined to be potential biological weapons. And again, after the anthrax attacks, the government became more concerned about potential biological weapons. And so Ebola was high on their list, so there was a lot of interest in funding to start to work on vaccines and therapies.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Because we like to do more than just talk about stuff when we do it we can, we actually have an example of one of those suits right here to show everybody. I want to ask them to bring it on out, right?

RICARDO CARRION: All right.

IRA FLATOW: That’s not Robby the Robot.

RICARDO CARRION: That’s Anysha. Anysha’s been with us since 2001. So Anysha, you’re going to try and put the suit on.

IRA FLATOW: So Anysha’s going to get into the suit.

RICARDO CARRION: She’s going to get into the suit.

IRA FLATOW: She can do this without any help. She can get in by herself.

RICARDO CARRION: Yes, she can. She does this–

IRA FLATOW: Let’s watch this.

RICARDO CARRION: Actually, she did this on Friday. She was working with Ebola on Friday. Now there’s a onepiece zipper on the suit itself. And we lubricate the zipper with actually a wax lubricant to minimize the amount of air going in and out of that suit. She’s going to step into like you would do overalls.

So these suits weigh about 15 pounds. In the old days, back in 2001, we had some made by the same company that makes the space suits. And those weighed about 25 pounds, so it’s much lighter to work with. But when you work in the laboratory, it’s like being in an airplane for the duration of your experiment because you’re under pressure. It takes some dexterity to be able to handle these small tubes.

So she’ll step in. You notice that she’s wearing a scrub top. That’s because on the way out, I mentioned we take a chemical shower. That scrub top gets removed and gets autoclaved as well. Now she’s going to put in her hands. Now we don’t have an air hose here, so she’s not going to be able to zip up too long. But she wears three pairs of gloves. So there’s one pair on the inside of the suit. There is a thicker pair on the outside. So they’re like dishwashing glove consistencies, so they’re thicker material.

And then if she’s in the laboratory, put a third pair on the outside. And they get swapped out every three entries into the lab, or if they have a hole in them, sooner. Of course you don’t want holes in your suits. And then she’s going to put the hood on, and there’s a zipper very quickly for a few seconds.

IRA FLATOW: So even the feeder attached. The boots are attached. That’s all in one piece. She’s zipping it up. Yeah, I see that.

RICARDO CARRION: Everything one piece. And in front, there is a little regulator that regulates the amount of air pressure that goes into the suit. So she–

IRA FLATOW: She’s all zipped up totally.

RICARDO CARRION: Yeah, exactly. There she is.

[APPLAUSE]

Again, go ahead and unzip.

IRA FLATOW: Thank you. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

Dr. Carrion, do you have to go through some kind of special training–

RICARDO CARRION: Training for the suit.

IRA FLATOW: –to wear that and to also work with the viruses?

RICARDO CARRION: Exactly. So everybody who works with Ebola virus has to go through first FBI background checks. So to make sure that you’re not prone to being a bad person, they do some general background checks on you. And then once you pass that, then we let you go into the laboratory. For somebody who is just starting out, it’s about six months at least before you’re allowed to work by yourself with Ebola virus.

If you work with– I mentioned we do vaccine and therapeutics testing. So we have to test these sometimes in animals. So if you do animal research, that can be up to two years before you can be allowed to work by yourself in the laboratories. Safety is very important.

Because you look at Ebola virus, the strain that we work with is 90% fatal, and there’s no cures, so no vaccines, no therapeutics. So if you were to accidentally poke yourself and get infected, you’re depending on your immune system primarily to fight off the infection. So we put a big emphasis on training.

IRA FLATOW: And Dr. Carrion, what makes Ebola so deadly? What kind of class of problem is it?

RICARDO CARRION: Ebola virus is a deadly virus because it primarily infects every cell type in your body. The course of infection– after infection, you have an incubation period that lasts anywhere from two to 21 days, and then you’ll start experiencing flu like symptoms. And when you’re in areas where it’s endemic like Africa, that’s one of the tough things about identifying Ebola virus, is because many things cause flu like symptoms, including the flu, and including malaria, and other endemic pathogens in that area.

But the virus itself is able to be infectious at very small particles. So in the laboratory, you work with a tube about this big, and you might have a milliliter. And that’s enough to kill 100 million individuals. So it’s highly infectious. So in an outbreak setting, we believe that bats are the primary reservoirs of Ebola virus. Individuals come in contact through a spillover event in which they contact a bat that has Ebola virus, but more likely, a non-human primate or some other animal that’s sick with Ebola virus.

As they become infected, family members take care of sick individuals, and they’re able to pass the virus on to each other. And if you’re looking at 90% case fatality, 90% of people that get these are going to die from Ebola virus. And the way it’s transmitted is through bodily fluids, saliva, vomiting, diarrhea. There was a lot of diarrhea with the last large outbreak Ebola virus in 2014. And that’s all full of this infectious virus that I just mentioned.

Currently, there’s no FDA approved treatment for Ebola virus. However, in our laboratory, we’re working on a number of these new investigational drugs, which look at monoclonal antibodies for treating Ebola virus. So it’s an antibody that our body produces. However, the pharmaceutical companies that we work with made these in a test tube essentially. And the antibody targets Ebola virus, and we’ve shown in our studies that we’ve been able to protect 80% of the animals that are infected with Ebola virus using these antibodies.

We’ve also worked for the last 10 years working on vaccines [INAUDIBLE] Ebola virus. So vaccines prevent infection. And currently with the last outbreak in 2014 and also the outbreaks now, some of the vaccines that we’ve tested here in San Antonio are actually being used in Africa during experimental vaccinations.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Let’s go to the mic, first on this side.

AUDIENCE: As far as the actual virus itself, you constantly hear about these flare ups and outbreaks. It is a very aggressive virus despite its incubation period. When we don’t have these outbreaks, these active events that are happening, where does Ebola go? Does it have an incubation period? Where does it hibernate, so to say?

JEAN PATTERSON: A lot of these viruses have what’s called a reservoir. And the reservoir is often an animal species. We don’t know what the reservoir of Ebola is. It’s suspected to be in bats, in fruit bats. One of the reasons we probably don’t have a lot of these hemorrhagic syndromes in North America is because we don’t have fruit bats. But for the most part, we don’t know yet exactly what fruit bat could be carrying Ebola.

So what happens is that Ebola is sitting in its reservoir, happily coexisting, working nicely. And then it jumps species. And that’s where we generally see outbreaks. When Ebola jumps out of its reservoir that it has co-evolved with forever and gets into a species that it hasn’t co-evolved with, and it causes the disease. And that’s called zoonotic transmission.

RICARDO CARRION: So actually one of the issues that we’re seeing now with such a large outbreak in 2014, 30,000 people infected, half of them survived. Now we see some of the survivors can still retain the virus in what we call immune privileged sites, like the eyeballs, the testes. So what this means is that months, years after an infection, the virus may be able to emerge and now cause a new type of hotspot, a new outbreak.

So one of the challenges that we have in developing therapeutics is that OK, we’re able to protect a person when they have therapy. But what happens three months from now or six months from now? What causes these viruses to hide in these sites like the eyes, and what can we do to target those, so that it won’t become a problem in the future? So even though we might be close to coming up with cures, and vaccines, and therapy, there’s still a lot of work to do on these secondary type infections that will occur because of this hiding in immune privileged sites.

IRA FLATOW: Let me just interrupt to remind everybody that I’m Ira Flatow, and this is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. Yes, let’s go to this microphone.

AUDIENCE: How long can you stay in suits?

IRA FLATOW: How long can you stay in the suits?

RICARDO CARRION: So as long as you can hold your bladder. So basically, there’s no bathrooms in the lab. But more practically, I mentioned it’s like being on an airplane for a long period of time. Well, when you’re working with Ebola virus, you want to be really focused. So after about five hours, you tend to lose focus. So we have a guideline that after five to six hours, if you’re not done with your experiment, you have to come out, take a break, go to the bathroom, eat something before you can go back in.

But it’s about five hours before somebody has to go to the bathroom. So when I was going in the laboratory– so now I’m older, so I don’t go in. But when I was doing it when I was younger and had much more hair, we would do things like not drink coffee before you go into the BSL 4. Stay away from Kung Pao beef right before you enter– to do things to regulate your metabolism because after four or five hours in there, sometimes you have to come out. And remember, there’s an eight minute shower. So you can’t wait until the last second when you’re in the BSL 4.

IRA FLATOW: I mean, we’ve talked about a lot of connections on 30 years of Science Friday, but never Kung Pao beef and a–

RICARDO CARRION: Kung Pao beef. Yeah, you got to be careful with that stuff.

IRA FLATOW: And a level 4 lab. Yes, question over here.

AUDIENCE: Hi. So you had mentioned the widespread outbreak in 2014, where it was all over the media, and many became aware of it. How does that kind of widespread knowledge and almost hysteria affect your research?

JEAN PATTERSON: Well, hysteria is never a good idea. And certainly there was a lot of hysteria associated with the outbreak in 2014, and that’s when I think it was 10,000 deaths, 15,000. Yeah, and that was the largest outbreak. And we didn’t really think that Ebola could ever produce an outbreak like that. That was news to us.

I think that the important thing is to remember that what we’ve been fortunate enough to have here in San Antonio is that when we built this lab, we told everybody. We went to all of the rotary clubs. We spoke to everyone that we could talk to and tell them what we were doing. We were going to build this lab to work on these global problems.

And San Antonio came back and said, well, of course we should have one here. Why aren’t you working on that now? And so I think with the attitude that San Antonio had was they didn’t do any of this not in my backyard stuff. They wanted us to work on things that are important for everybody.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Now we’ve run out of time. Very interesting conversation. I want to thank both of you, Dr. Jean Patterson, professor at Texas Biomedical Research Institute, Dr. Ricardo Carrion, professor and director of maximum containment contract research at Texas Biomedical Research Institute. And special thanks to our suit specialist.

RICARDO CARRION: Thank you, Anysha.

IRA FLATOW: Anysha Ticer. Let’s give it up for her, too. So thank you all for taking time to be with us.

[APPLAUSE]

That’s about all the time we have. Our heartfelt thanks to Nathan Cone, Wendy Wommack, and all the great folks at Texas Public Radio for hosting us.

[APPLAUSE]

Thanks. Thanks also to Christopher Novosad, Sean Jenkins, and all the wonderful folks at the Tobin Center for the Performing Arts for making this wonderful evening possible. Thank you all.

[APPLAUSE]

Let’s give one last round of applause to our musical guests, [INAUDIBLE] who will play us out tonight. Thanks for coming. In San Antonio, I’m Ira Flatow. Drive home safely, everybody.

SPEAKER: Thank you, Ira Flatow and the Science Friday crew. Thank you, Tobin. Thank you, San Antonio. This song is dedicated to the beautiful people of El Paso.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Katie Feather is a former SciFri producer and the proud mother of two cats, Charleigh and Sadie.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.