How Do They Actually Store The Declaration Of Independence?

17:41 minutes

These days, the 4th of July is known for its fireworks and cookouts. But the holiday commemorates the ratification of the Declaration of Independence, one of the most important founding documents of the United States.

The Declaration of Independence, alongside the Emancipation Proclamation, the Constitution, and countless other documents, is housed in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Like any other museum, the National Archives doesn’t just house these items, it preserves them, protecting them from the degradation that happens over time.

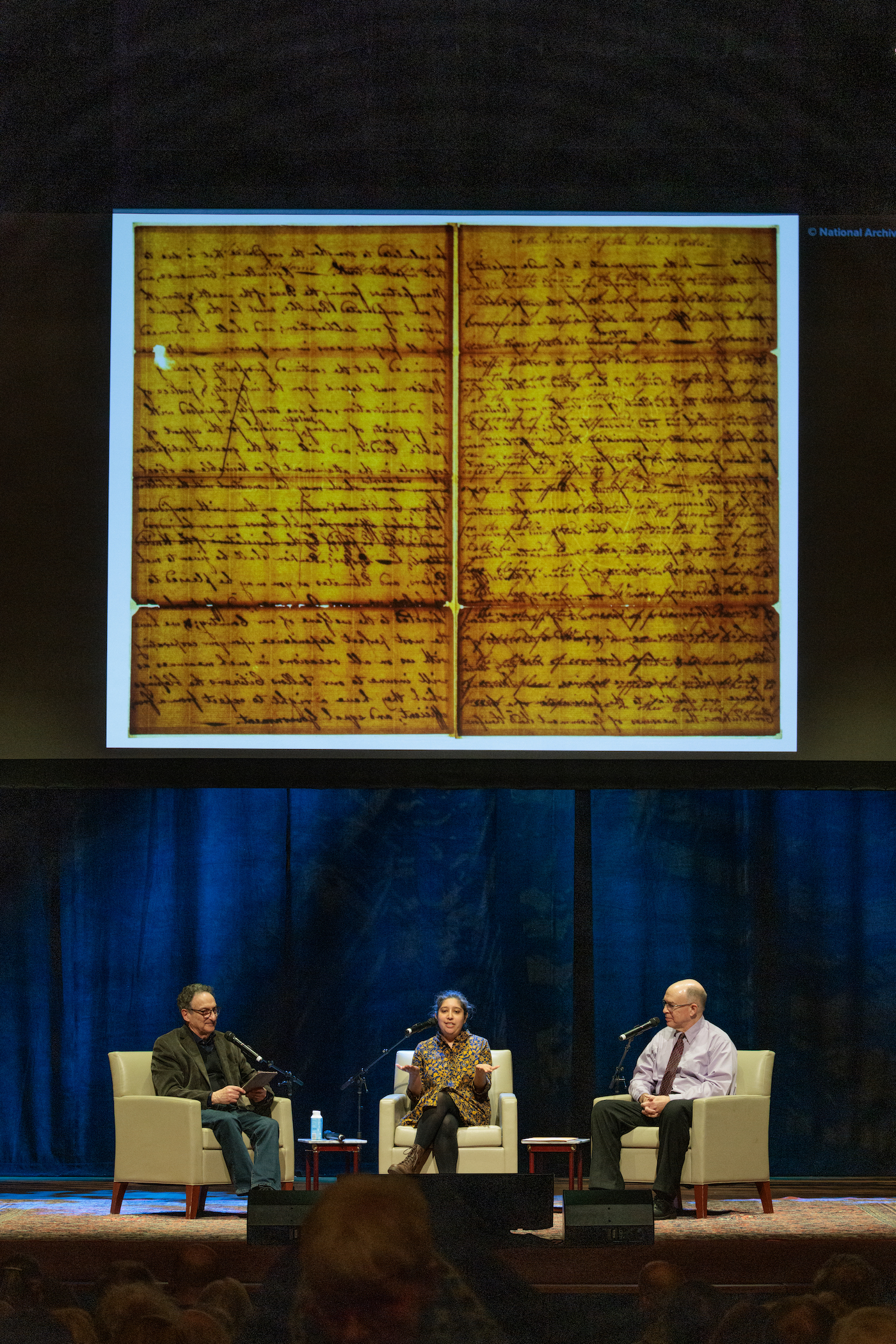

In March, at SciFri Live in Washington, D.C., Ira spoke to two restoration experts about what goes on behind the scenes of the National Archives: Conservator Saira Haqqi and physicist Mark Ormsby. They discuss the history of papermaking in the US, changes in restoration science, and what “National Treasure” really got right.

Saira Haqqi is a conservator with the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Mark Ormsby is a physicist at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow.

As you know, Independence Day marks the ratification of the Declaration of Independence, and I have always found it a treat to see the original stored behind glass at the National Archives in Washington. The Archives store many other national treasures too, documents important to the founding of the United States. And the Archives must preserve all these documents for future generations. That means a lot of science goes behind this preservation.

Last March before a large audience, I interviewed the archivist in Washington, and they revealed how it’s done. Have a listen.

Saira Haqqi, Senior Conservator at the National Archives, and Mark Ormsby, Heritage Scientist at the National Archives, welcome to Science Friday, both of you.

SAIRA HAQQI: Thank you. Excited to be here.

MARK ORMSBY: Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]

IRA FLATOW: Now, the National Archives has 13 and 1/2, Mark, billion pieces of paper.

MARK ORMSBY: That’s right.

IRA FLATOW: –in its archives. That’s billions with a B.

MARK ORMSBY: With a B.

IRA FLATOW: Well, we think of big, flashy things like the Declaration of Independence, but what other kinds of items are there in these billions in the Archives?

MARK ORMSBY: Well, we have pension records, which are an important source of information for genealogists. We have a huge collection of photographs, motion pictures, maps. We have one of the largest collection of maps in the world.

IRA FLATOW: Maps?

MARK ORMSBY: Yes.

IRA FLATOW: And what about the speeches that all our politicians make and things?

MARK ORMSBY: We preserve those as well. We have a big audiovisual collection. We have one of the largest motion-picture collections, at least in the US. I’m not sure if that’s in the world.

IRA FLATOW: You know, I remember seeing the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark where they put they put the Ark away. The Ark, is it something like that, look something like that?

MARK ORMSBY: It’s right next to Rosebud.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah.

[LAUGHTER]

That’s good. That is very good.

MARK ORMSBY: Glad that reference made it through.

IRA FLATOW: Well, I mean, if you’re taking care of something as delicate and valuable as the Declaration of Independence, does your hands sort of shake when you’re realizing what you’re working on?

MARK ORMSBY: Well, I’m a scientist. I’m not a conservator like Saira. So the conservators are the ones who have been trained. They go through– most of them have master’s degrees. You don’t just walk in and start– sorry, I’m quoting the movie already. You don’t just conserve the Declaration of Independence. You have to go to school for that.

IRA FLATOW: I kind of thought you did.

MARK ORMSBY: Well, in Hollywood. But yeah, it’s a long, very careful process.

IRA FLATOW: Do you conserve other copies of this? I mean because, what, about a half a dozen other copies were made or more of the Declaration. Do they come to you, whatever, and say, help us conserve this or help us store it?

MARK ORMSBY: Well, we’re a federal agency, so people consult us all the time with questions. We get a lot of questions. Someone finds a copy of the Declaration of Independence, and they’ve heard that, hey, somebody found this in their attic and sold it for $500,000. Well, unfortunately, when there’s typewritten text at the bottom, that’s a pretty good sign it’s not the original.

IRA FLATOW: Dead giveaway all the time. Saira, a lot of the documents you conserve are hundreds of years old. And you’re always working with the same kinds of paper, or are there different kinds of paper that you work with?

SAIRA HAQQI: So that’s a really good question. There’s a big range. So some of our documents are actually on parchment, so that’s not paper at all. That’s animal skin. And then most of what I end up dealing with is probably 18th- or 19th-century paper, and that’s right when there was a change in the quality of paper and in paper manufacturing. Basically you started to– traditionally paper was made out of cotton rag, which is real nice. It’s beautiful paper. If you look at a good medieval book, like that paper will last forever, provided you don’t dunk it in water.

But you only had so many cotton rags. It was literally like a rags of what people wore.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. There was a shortage of rag at one point.

SAIRA HAQQI: There was a shortage.

IRA FLATOW: During the Revolutionary War.

SAIRA HAQQI: Yes, absolutely. And so people were trying to figure out different ways of making paper, and they made paper out of– around 1800, there was a guy who printed a book on paper made of straw, Matthias Koops, who’s one of my favorites, I guess was like, why not? And then during the Civil War– or no. Yeah, I think it was during the Civil War, there was somebody who started making paper out of mummy wrappings because I guess mummies were cheap at the time–

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

SAIRA HAQQI: –to get hold of. And again, why not? Human ingenuity is just always inspirational.

IRA FLATOW: Mark, when you go to the National Archives, you always see these documents in big glass cases. What is the case, the glass? What’s inside? What’s the gas inside? What’s going on behind that glass and in the case?

MARK ORMSBY: So the charters, as we call them, the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, which are on permanent display, they’re in special cases where we’ve removed the oxygen, removed the air, and put argon in place, with the idea that argon being an inert gas, it helps to prevent chemical reactions that might affect the parchment surface, possibly also the ink.

That’s a complicated issue because these inks, you didn’t just go and buy the standard formulation. People came up with their own. They threw rusty nails in. They threw all sorts of things. So there’s a big variety. So some of them turned out to be acidic and ate the papers. Some are in beautiful condition. So there’s a wide range and a lot to study.

IRA FLATOW: Now, if this is your turn to ask questions, we have the mics down here, if you’d like to come and ask questions about conservation that’s going on and how it’s done. There’s a mic in this aisle, and there’s a mic in this aisle.

Let me see who’s ready. We have a question already. Ready to go right here? Go ahead.

AUDIENCE: How do you decide what to conserve, what to protect, what to keep in there? And how do you coordinate with the other– like the Library of Congress, et cetera? And secondarily, what’s the gender breakdown? What’s the gender breakdown of what you’ve preserved? Because women’s records were not as retained over many decades, over many centuries. So how do you focus on that as well?

IRA FLATOW: Saira?

SAIRA HAQQI: So that’s a really good question, and it’s a question that, honestly, I am not the person who decides what ends up in the lab. So this is a little bit above my pay grade, to be entirely honest.

But I think there’s a lot of different aspects to consider, and the National Archives, it’s a federal agency. It’s also a research institution. We are guided, to some extent, by user interest, I would imagine, to some extent.

And just to get back to the second part of your question, so yes, in some ways, like the US government– most governments were not really tracking women in the same way as they tracked men’s work. So that does bias archives in a certain way, and it archives a lot of collections around the globe in a certain way.

But you do see– like for instance, the pension records that we were talking about. They’re technically relating to the service of a soldier, but they usually also involve the soldier’s widow filing to get his pension after he passes. And so a lot of times you’ll have the signature of the women, their names, or what I find it always hits me a little is you’ll have a cross. You’ll just have an X because whoever the person was couldn’t sign her name.

Or another project I’ve been working on a lot is the 1960 census, and that’s the census. So you can get certain types of information from records, even if maybe what they were looking to preserve at the time– because we are limited by what people in the past thought was important. And that’s just always kind of going to be the problem. Like, we’re never going to know what’s going to be important in the future.

IRA FLATOW: Question from the audience. Yes?

AUDIENCE: OK, Science Friday, I have a question. What is the security like in the Archives? If somebody were trying to break in, what would the defense be?

[LAUGHTER]

SAIRA HAQQI: Well, you know, we do have these guns that come up out of the floor. No, go ahead. Mark, I think you might be better for this one.

MARK ORMSBY: Considering my boss isn’t in the audience, I’m going to say no comment.

[LAUGHTER]

I will say we renovated the building about 20 years ago, and you can go online. You can see a YouTube video of the old vault, and it would raise up out of the floor every morning and go back down at night. And I can just say that that was designed to show the documents. They were supposed to go in. It was really difficult to get them out and extremely nerve wracking. As far as the new system, I’m not going to comment about that, just to say that it’s not nearly as terrifying as the old one.

IRA FLATOW: There used to be talk back in the day that during a nuclear attack, the documents would automatically go into their vault. Is that correct?

MARK ORMSBY: I tried to track down where that came from. It’s pretty impressive that a direct– it went from being fireproof to being bomb proof to being nuclear proof to being a direct hit at ground zero proof. So I’ll just leave it at that.

IRA FLATOW: OK. OK. Yes, over on this side. Yes, you can go ahead.

AUDIENCE: What was the most expensive or rare document that has ever been destroyed in the restoration process?

[LAUGHTER]

SAIRA HAQQI: Ooh.

IRA FLATOW: Next question, please.

MARK ORMSBY: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: What was the most expensive– I’m going to give her time to think about this by repeating the question.

SAIRA HAQQI: Yeah, I don’t know. I haven’t heard of a document being destroyed. I think because most of the time– so I can tell you what we do to make sure we don’t do that because that is– this is the thing. As a person who works with cultural heritage, you work with cultural heritage all the time, and that means that the odds of your destroying something are higher than if you did not do that.

So one of the things that we do is we photograph, usually, if we’re doing the kind of conservation treatment that will significantly change an object or has the potential to significantly change an object, including destroying it. We photograph it usually beforehand. It is very well documented so that if it is lost, then the information that it contains is still preserved in some form.

In addition to that, I didn’t just take that document and dunk it into water. I tested each of the solvents that I was going to use on that document on each of the inks and media and the paper before I did anything as drastic as immersing it in water.

This isn’t foolproof because, obviously, putting something into water as a whole document for a certain amount of time is going to be significantly different from spot testing it. But it does kind of give you a sense of what might happen.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah. No, because you put something in my head about what you do and what you’re looking at that other people have done before you a hundred years from now. Do you think– of a hundred years before. Do you think a hundred years from now they’re going to look at your work and say, what were they thinking of about preserving it?

SAIRA HAQQI: Absolutely. This is one of the fears of the conservator that we just have to live with. You have to live with the knowledge that you might be truly ruining something at any given point.

[LAUGHTER]

And one of the ways that the profession has developed to deal with this is to apply a principle of reversibility. Which is to say that a lot of the adhesives we use or most of the adhesives we use, we try to make sure that they are going to be reversible at some point, that you can take off what you just stuck on.

There’s a whole literature of debate around how successful this is in the field, but that is a principle that a lot of us were trained in coming up. And it’s there, but at the same time, if I clean a document, that grime ain’t going back.

IRA FLATOW: You do the best with what you have at the time.

SAIRA HAQQI: Exactly. You do the best that you can with what you have, and you hope that you’re dead before–

[LAUGHTER]

–anyone figures out that it’s not–

IRA FLATOW: That’s how I figured about my job also is, you know, do the best we can and hope. Yes, question over here.

AUDIENCE: What part about the documents do you find the most interesting?

MARK ORMSBY: Well, I can say just a few weeks ago, we were doing a multispectral imaging project, and we had the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and the Emancipation Proclamation right next to each other on the table. And the preliminary was written in, let’s see, September 1861, I believe. And then the Emancipation Proclamation was signed by Abraham Lincoln a hundred days later on January 1, 1963. I think I have the dates right.

And I’d been reading about them, and the focus tends to be on Lincoln’s political strategy and how that fit into the war and everything and, of course, how that affected enslaved people or the whole debate around slavery. But to see them on the table next to each other– which they probably haven’t been next to each other like that in a long time. I was really struck by those 100 days, that must have been a lifetime for enslaved people. Here’s the promise made in the preliminary, and is it really going to happen? So that was one of the highlights.

IRA FLATOW: I can’t think of a better time to end this discussion with that story. Thank you very much for taking the time to be with us today. Mark Ormsby, heritage scientist at the National Archives, and Saira Haqqi, senior conservator at the National Archives, thank you both for taking time to be with us.

SAIRA HAQQI: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: Now we’re going to take a few minutes to reset and listen to the wonderful music of Elena and Los Fulanos.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Kathleen Davis is a producer and fill-in host at Science Friday, which means she spends her weeks researching, writing, editing, and sometimes talking into a microphone. She’s always eager to talk about freshwater lakes and Coney Island diners.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.