Former NIH Director Reflects On Public Mistrust In Science

16:45 minutes

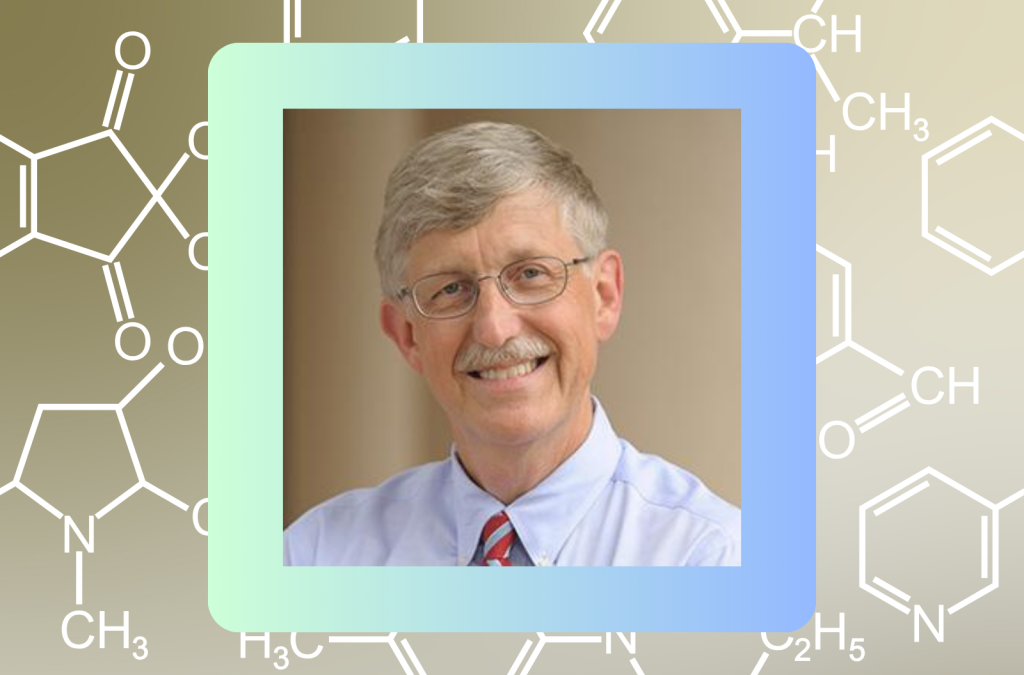

In 2021, Dr. Francis Collins stepped down after a dozen years leading the National Institutes of Health. He had just overseen the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic,in the early days of changing public health guidance as scientists learned more about this new virus. He was also involved in the quickest development of a vaccine in history.

Now, he’s had some time to reflect on how the US arrived at such a divisive place about COVID-19 and vaccines, how trust in science has dwindled, and what we can do about it.

Ira sits down with Dr. Collins to talk about the lessons from his new book, The Road to Wisdom: On Truth, Science, Faith and Trust, and why he decided to speak publicly about his prostate cancer diagnosis.

Dr. Francis Collins is the former director of the National Institutes of Health, and author of The Road to Wisdom: On Truth, Faith, Science and Trust.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. The last time I spoke with Dr. Francis Collins was way back in 2021. He was about to step down after a dozen years leading the National Institutes of Health. He had just overseen the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the early days of changing public health guidance as scientists learned more about this new virus. And he was involved in the quickest development of a vaccine in history.

Now he’s had time to reflect on how our country arrived in such a divisive place about COVID-19 and vaccines, how trust in science has dwindled, and what we can do about it. And he’s written it all down in his new book, The Road to Wisdom, On Truth, Science, Faith, and Trust. Dr. Collins, welcome back to Science Friday.

FRANCIS COLLINS: Hey, Ira. It’s great to be with you. And please call me Francis.

IRA FLATOW: OK. OK, Francis. [LAUGHS] The book’s titled Road to Wisdom. Why did you decide to make wisdom the central focus of your book? What is the wisdom you’re talking about here?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, what is wisdom, anyway? It’s certainly based on knowledge. And as scientists, we’re all about trying to discover things that add to knowledge.

But wisdom adds some additional layers to that, the ability to sift through a difficult decision when you don’t have enough information and try to do the wise thing. I think we all really strive to be on a road leading to wisdom. I do. It’s not a destination you just get to, and you’re done.

But I think individually and collectively, we’re kind of in a bad place right now where a lot of us have spun out, hit a pothole, somehow ended up in the ditch. And this book is a call to try to pull ourselves back together again and get re-anchored to things like truth, science, faith, and trust so that we can travel that road more productively and help humans not just fight with each other, but flourish.

IRA FLATOW: Tell me more about that ditch. What do you see as that ditch? What is it to you?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, a big part of it is what seems to be a loss of appreciation of the fact that there is such a thing as objective truth in our society. And facts that are well established in history or by scientific approaches to understanding nature are sometimes just a matter of opinion, and alternative facts get put forward as if they had the same weight. That’s a very dangerous place, and that certainly causes some falling into ditches if you’re looking for wisdom.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Let’s talk about an event in particular. You describe participating in an event with Wilk Wilkinson, a Christian conservative podcast host. And the event has an intriguing title, An Elitist and a Deplorable Walk Into a Bar.

FRANCIS COLLINS: [LAUGHS]

IRA FLATOW: Right? He’s been vocally opposed to the government’s handling of COVID-19. Many people in your position would have declined the invitation. So why did you decide to participate in that?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, Ira, I was really troubled as I stepped down from NIH about how we got so polarized about something that’s a scientific issue, the management of COVID. And I needed to understand more about why such a significant fraction of the public– good, honorable people– didn’t see it the way that I did.

So I signed up to join a group called Braver Angels, which intentionally brings people together who have very different opinions about hot topics like, oh, abortion, for instance, or gun control, or immigration, or public health. And taking part in a number of those sessions, I met Wilk, who had a firebrand’s approach to criticizing what had been done with COVID, but was willing to listen to alternative perspectives.

And that’s what Braver Angels really tries to get you to do, to listen. Not to plan your snappy response, but to actually understand the perspective.

And I began to get it. Here’s a guy from Minnesota. Runs a trucking company. What happened with COVID seemed to him to be driven by recommendations that were a good fit for a big, urban city like New York, but not a very good fit for his small town.

And his business got injured, and his kids got hurt by being out of school for a long time. And he was puzzled by the shift in recommendations about what to do about things like masks, and so he got pretty disillusioned. I needed to hear that. I needed to actually take on some responsibility for some of the science communication that could have been better.

And so we agreed that in this gathering of the Braver Angels annual meeting in very symbolically located Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, that he and I would have a debate in front of this part blue, part red audience, and try to model how you can disagree but not be disagreeable, how you can express your view, but also be sure you’re listening to the other person. I still think Wilk is wrong about a lot of stuff. [LAUGHS] He thinks I’m wrong about a lot of stuff. But we’re pretty good friends who enjoy having a beer together.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. You mentioned admitting failures in communication during this COVID, as you just said. And you write in the book, quote, “I learned that failure is not an affront to science. It’s an element of science.” Failure is standing on the shoulders of giants who may have failed, right? What is failure in your own career, and what do you think you learned most from it?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, going to the communication part, I think we failed to explain the uncertainty of the situations we were facing during 2020 where we knew only a little bit about this virus and had to make recommendations that were the best we could do. And we would have benefited the public, I think, to be more in tune with that so they didn’t think we actually had definitive answers when they were still forthcoming.

For me personally, failure’s been a big part of how I’ve learned about science. And in the book, the very first couple of pages, I talk about my very first effort to be a molecular biologist as a postdoc at Yale, carrying out an experiment that I had great hopes for, and was an absolute and complete, utter disaster after six months of work with nothing retrievable from it.

And I almost quit. But then I realized after a lot of consultation with more experienced people, this is maybe the most important thing you’ve ever done. Figure out, how did that failure happen? How did you not really plan thoughtfully that experiment in a way that could have anticipated this was going to go wrong? And then the next time, you’ll be in a much better position to do something that works.

IRA FLATOW: You know, during your career– and I remember we have talked about this in our past conversations– you have always been held up as a model of a religious person, a Christian, who is able to not let your Christian views absolutely interfere with your science and your approach to being a scientist. How does that happen? How are you able to do that?

FRANCIS COLLINS: [LAUGHS] Well, I know people are puzzled about that. At least, some are. I think it comes down to, what kind of question is being asked? And which framework do you use to try to answer it? If it’s a question about how nature works, hey, that’s a scientific question. Let’s use all the tools of science, and let’s be as rigorous as we possibly can in assessing the data before we accept a conclusion.

But if it’s a broader question like, why am I here, and why is there something instead of nothing, and what really are the ethical boundaries, and where did they come from in terms of our decisions about what kind of science we actually believe is moral, then there’s got to be another perspective. I don’t keep my scientific perspective and my faith perspective often separate parts of my brain. I think they interact pretty effectively. But I do feel really careful about not mixing up the questions that are being asked and using the wrong approach to them.

You know, faith is a way to answer fundamental questions that start with why. Science gives you the answers to the how in wonderful ways. But I want to know both how and why.

IRA FLATOW: But what about when people who are faith leaders spread health misinformation like we’ve seen during COVID? And then their followers also mistrust science, like we’ve said. How do you navigate that when leading the NIH?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Yeah. Well, that certainly has happened. But let’s be clear, there’s a lot of misinformation being spread by people who have no faith basis at all that are simply out there spreading conspiracies, and maybe making money as a result. And social media has greatly accelerated the dangers there of how information can suddenly go viral that had no basis in fact at all.

With faith leaders, I’ve done my best to try to stay connected with that group. These are wonderful, honorable people trying to do what they can to take care of their flocks, and barraged by messages coming at them. And sadly, a mixing up of faith, foundations, and political messages, which has done, I think, harm to the basic ways that many people look at faith traditions. So we have a lot of work to do there too.

And a wonderful document just came out, signed by hundreds of evangelical pastors and leaders, calling the church to come back to its foundations on truth and love your neighbor and grace, and not being so quickly seduced into this idea that you need to have political power. Political power is the opposite of what most faith traditions, certainly Christians, were called to, but we’ve lost that thread somewhere.

IRA FLATOW: We’ve talked about the pandemic showing a widening gap in the trust in science and the scientific process among different groups of people. And it’s not just COVID where that crisis of confidence in science exists, because I can recall 15, 20 years ago on this show talking about vaccinations.

And you know– and there were people who told us on that show that they just don’t trust anything their government tells them, right? You know, here’s the research that’s shown. Oh, but it’s done by the government. How do we get that trust back in government and talking about health?

FRANCIS COLLINS: And it certainly accelerated during COVID with more than 50 million Americans declining to take the vaccine that was sponsored by a wonderful partnership between industry and academia and government and showed remarkable efficacy and safety. And yet, 50-plus million people said, no thank you.

And these are good, honorable people, but that suspicion about government has been allowed to grow. And it’s had those flames fanned by lots of voices out there, including some people in the government itself who seem to enjoy the chance to trash the whole institution that they supposedly are part of.

So how do we deal with that? In the book, one of the things I call people to do who are willing to be part of the solution here is to look at your own portfolio of facts that you’ve brought on board and considered to be established, and make sure there are not things in there that found their way into your belief system based upon something that wasn’t actually true. That’s a bit of work.

And then how do we, going forward, set up a better filter to distinguish facts from fakes? And that means you look at the source. The expertise really matters. And somebody who’s worked on a project or an issue for 20 years is more reliable than somebody who just posted something on Facebook. A lot of that has gotten muddled up and mixed.

And a really outrageous claim ought to be looked at with particular care to be sure that it’s not somebody manipulating you. But it’s going to require each of us to take on a personal attitude that goes beyond saying, things don’t have to be like this, to saying, I don’t have to be like this.

And even to consider making a pledge, which is in the book in the last chapter and is posted on the Braver Angels website, making a commitment to a couple of things. One is not to spread around things unless you’re sure they’re true. Another is to try to actually get to know people who disagree with you, like I did with Wilk Wilkinson, so that we become less polarized, more willing to do the bridging between different opinions, which is what a healthy society would do.

IRA FLATOW: This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios. I want to pivot a little bit to talk about something more personal with you, and that is you being diagnosed with prostate cancer this past spring. Why did you decide to talk about that very personal thing publicly?

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, of course, it was not a diagnosis that I was hoping would ever happen to me, but there it was. I had been followed closely for four or five years with what appeared to be a not very threatening type of very low-grade prostate cancer. But then it changed and became much more aggressive, and action had to be taken.

I was aware that an awful lot of men around me, as they heard about this, kind of cringed. Like, oh, boy, that’s something I don’t want to talk about. But you know, we’ve made a lot of progress, Ira, in terms of early screening, early detection, better imaging, targeted biopsies. There’s all kinds of ways now to make prostate cancer a precision medicine approach. But a lot of people don’t know that yet, and they’re afraid of it.

My own prostate cancer had a detailed genomic analysis done and identified a driver mutation that might have been responsible for why it suddenly became much more aggressive. This was so interesting being on the receiving end instead of the producing end of genomic science.

So I figured, OK, I’m going to tell the world, even if it does make people a little bit cringey, and [LAUGHS] see if it will wake up some component of the population, the men, to whether they might want to consider being a bit more careful about their own surveillance. And I hope it helped.

IRA FLATOW: I want to talk a bit about your work on hepatitis C. I know you’ve been very active in this. And last year, President Biden appointed you to lead this White House task force to eliminate hepatitis C. What motivated you to get involved in this work, and how is it progressing?

FRANCIS COLLINS: I’m glad you’re asking, because I’m pretty obsessed about this. The development of direct-acting antiviral, small molecules against hepatitis C I believe ranks as one of the most amazing achievements of medical science in the last 20 years. This is one pill a day for eight to 12 weeks. 95% cure rate. No side effects.

And this is a terrible disease that currently infects about four million Americans. And without that treatment, those folks are headed for liver failure, liver cirrhosis, liver cancer, and early death.

So why haven’t we solved this? Because the drugs have been approved for eight years. It’s because a lot of the people who need the treatment are in underserved populations. They may be people who have experimented with intravenous drugs. They may be people in the prison system where in some prisons, as many as 20% or 30% of people there are hep C positive, again, because of the interaction with drugs.

This is not right. If we have the chance to cure people– first of all, it’s not right morally. It’s also not right economically, because the cost of taking care of all these cases of liver failure who might need a transplant or liver cancer that doesn’t respond very well, is in the tens of billions of dollars for our country if we do nothing.

So how can you look at that situation and say, oh, well? If we can save potentially tens of thousands of lives, which I think we can, then we’ve just got to do it. And there’s bipartisan support for this led by Senators Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Chris Van Hollen of Maryland– that’s a Republican and a Democrat– with a lot of other bipartisan interest.

And I believe this could get voted on positively before the end of the year, and President Biden would most certainly sign it. And we could launch this program in 2025, and we could save tens of thousands of lives and tens of billions of dollars.

IRA FLATOW: Francis, I want to thank you for taking time to be with us today, and it’s a wonderful book.

FRANCIS COLLINS: Thanks, Ira. Good to talk to you.

IRA FLATOW: Dr. Francis Collins, former Director of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and author of the new book The Road To Wisdom, On Truth, Science, Faith, and Trust.

Copyright © 2024 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Shoshannah Buxbaum is a producer for Science Friday. She’s particularly drawn to stories about health, psychology, and the environment. She’s a proud New Jersey native and will happily share her opinions on why the state is deserving of a little more love.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.