Randall Munroe’s ‘How To’ Guide For Everyday Problems

27:37 minutes

If you’ve ever been skiing, you might have wondered how your skiis and the layer of water interact. What would happen if the slope was made out of wood or rubber? Or how would you make more snow in the most efficient way if it all melted away? These are the questions that comic artist Randall Munroe thinks about in his book How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. He answers these hypothetical scenarios and other everyday questions—from charging your phone to sending a digital file—with uncommon solutions. Munroe joins Ira to talk about how he comes up with his far-fetched solutions and why “…figuring out exactly why it’s a bad idea can teach you a lot—and might help you think of a better approach.”

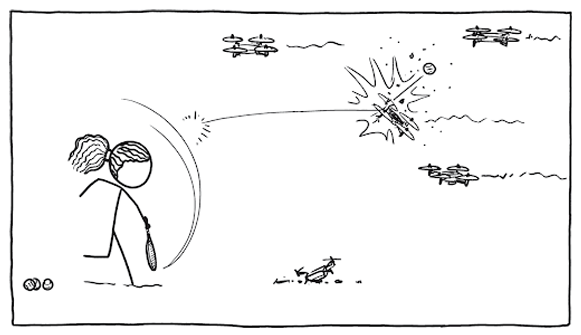

Read an excerpt of Munroe’s new book where tennis legend Serena Williams takes to the court to test one of his hypotheses: How to catch a drone with sports equipment.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Randall Munroe is a comic artist, creator of xkcd.com, and author of Thing Explainer: Complicated Stuff in Simple Words (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015) and What If?: Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014). He’s based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

IRA FLATOW: Have you ever found yourself pondering an idea that sounds wacky at first, but you still would like to know, right? To come up with an idea like, can you land an airplane on a submarine? Sounds wacky? Can you do it? My next guest likes to ponder absurd solutions for simple ideas.

For example, his solution for filling up a pool– it involves harnessing the water from the air. And his idea for catching a drone involves having tennis star Serena Williams hit tennis balls at the flying copters, and he actually had her do that. We’ll talk about what happened.

In his new book, How To, Munroe works out the math and the science behind the most complex solutions to simple questions– because he says, figuring out exactly why it’s a bad idea can teach you a lot and might help you think of a better approach.

Randall Munroe is creator of the webcomic xkcd.com, and his new book is called, How To– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. And we have an excerpt of his book on our website, sciencefriday.com/howto. Nice to talk to you, Randall.

RANDALL MUNROE: Hi, Ira. Thanks for having me.

IRA FLATOW: And it’s quite– this is a great book. It’s got all kinds of–

RANDALL MUNROE: Thank you.

IRA FLATOW: –things that I have thought about in my spare time while I’m driving– how crazy would it be to do that? And you’ve actually figured out how to do some of these things. And you mention in your book that your solutions take a lot of detours. Why make it so hard for yourself? Why did you want to figure out the most complicated solution for finding something?

RANDALL MUNROE: Well, the truth is, I’m not trying to find the most complicated solution. I just tend to– and I have a problem or some task to do, sometimes there’s an easy way to do it, but it’s kind of repetitive or kind of difficult. And I’m always trying to think, what are some other ways I could do this? I’m not trying to think of particularly good or bad ways, just other ways that I can then think through.

Like moving, for example, where packing boxes is really difficult. And so I start wondering– like I see houses on trucks sometimes. Could I just skip the move by lifting up an entire house? Which then creates a bunch of new problems, like how do you lift a house? How do you detach it from the foundation? Do you need to get wide load permits for each jurisdiction you travel through? And then solving each of those problems– trying to think how I’d do that– leads me to new ones.

IRA FLATOW: Our number– 844-724-8255. I know our listeners are going to have suggestions for how to do things, and maybe you’ll have the answers for them. And one of your questions is how to throw things– that starts with a story about George Washington throwing maybe a dollar over the Potomac? How did you come up with that question?

RANDALL MUNROE: If you’re thinking about different ways of throwing things, you think, well, who’s really good at throwing? And there are all these stories about George Washington. I think most of them come from after he died. There were a bunch of– there’s a big market for Washington stories.

So in some versions it’s one river, and sometimes it’s the Rappahannock. Sometimes it’s the Potomac. Sometimes it’s a silver dollar. Sometimes it’s a rock. But the general agreement seems to be he threw something over some river, and it was very impressive.

And so I was looking at, OK, can we come up with a model for how far it is practical to throw things? And I use that story as an example, because I really like that you can come up with sometimes these really simple physics models, and just do a little bit of math on a piece of paper and suddenly get an answer about whether something is possible or not.

IRA FLATOW: I want you to tell the story, because it was really fascinating– the Serena Williams story– the idea of how to swat or catch a drone involving tennis star Serena Williams hitting tennis balls at it. How did you talk her into that?

RANDALL MUNROE: Well, I was surprised. So that was something I got to do with this new book that I’ve done a little bit before, but I got to do more here– was reach out to people who know about how to do really cool stuff and ask them for advice, and occasionally to do some kind of experiment. I was really surprised, because I always felt like, oh, these people all have better things to do. I’m bothering them. But people were all so enthusiastic and so excited to help out.

And so I had been thinking about when you see one of those wedding photography drones floating around. And you don’t really know who’s controlling it, and you kind of want to get rid of it. There are all these high-tech ideas for what to do about them. But I was thinking, what if I’m just in my backyard and I’ve got a couple of– there’s a basketball and a baseball and stuff. I started wondering, would you be better off throwing a baseball at a drone or a basketball or a football? They have different pros and cons.

And this led me into wondering about, overall, what sports equipment would be best for hitting a drone? And so I found a bunch of research on this– research on accuracy in different sports– how far, how fast, how precisely can baseball players throw baseballs and how accurate our soccer kicks. And so I started trying to work out, which projectile from which sport would be best for hitting drones?

And one of the ones that I was having trouble finding data on was tennis. I just hadn’t come across any studies yet that were useful for this particular model. And I knew Alexis Ohanian, Serena Williams’ husband, from a long time ago. We were acquaintances. And he had texted me about something, and I mentioned, oh, I’m working on this tennis problem– this tennis puzzle. And he said, oh, hey, if there’s any way we can help out, let me know.

And so I was of course excited. So I asked– he put us in touch. I asked if Serena could maybe, when she’s at practice– I don’t want to take too much of her time– maybe put up a little target on the wall and hit a ball at that. And then if they could take a video and give me the measurements of the room, I can use that to build a model to figure out how effective she’d be against an actual drone.

But to my surprise, it turned out they had an actual drone and were happy to take that out onto the court. And so she did. She had someone fly the drone out over the middle of the court, while she stood at the end and tried to see how many serves it would take to hit it.

IRA FLATOW: And she did better than your prediction, right?

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah. I was trying to guess based on what I could find about tennis pro accuracy. And I had come up with– I think I had guessed about five to seven serves from that distance with that model drone as the target. And she got it in three. So it could just be a statistical outlier. I sort of suspect it’s just that Serena Williams is an outlier.

IRA FLATOW: She is that good. I’m Ira Flatow talking with Randall Munroe. How To, the book is called– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. Like you want to take down a drone– that’s a common real-world problem. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios.

Did you have to limit the kinds of things you wanted to publish or include in the book? Because there are so many different things that people ponder.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah. I always find with any problem if the answer is too easy, I always will find a new problem to solve that’ll make it more complicated again. So I mostly had to limit myself from– the research would always– every new question that I asked would take me down a new research rabbit hole.

And so the way I think about it is, I try to then– once I’ve found as much as I can, I kind of back up out of the rabbit hole and say, what are the coolest things that I found in all these individual problems I solved? And how can I pull them together? And so this book is sort of the compendium of me starting with a bunch of simple problems and doing that process until I was out of rabbit holes to go down, or at least out of energy.

IRA FLATOW: Well, you sometimes had some help. For example, you interviewed astronaut Chris Hadfield to figure out different scenarios for making an emergency landing. Had he already thought about those questions?

RANDALL MUNROE: Well, I was really surprised. I was going to ask– I wanted to do a chapter on how to land a plane– how to do an emergency landing. And so I reached out to him because Colonel Hadfield is the commander of the International Space Station and also a really accomplished test pilot. So I thought he’d be a good person to ask.

But I was expecting him to– I was going to ask how you would land in ever more silly situations. And I figured I’d start with the more normal ones and then work my way up to the more and more ridiculous ones, and then figured at some point he would say, this is a waste of time and hang up on me. But to my surprise, he seemed– first of all, happy to answer as many questions as I could throw at him.

And second, he had an answer for everything right away. I would ask him about the strangest thing I could think of, like could you land a plane if you had to land on top of a moving train? And instead of saying, that’s a ridiculous question, he would say, oh yeah, people have done that. And then he’d start listing off other vehicles that people have landed planes on and under what circumstances, and what you have to do to land them.

And so I discovered that my plan to try to fluster a test pilot by throwing weird extreme situations at him without warning might have been flawed. But it ended up being my very favorite chapter in the book.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, you talked about landing a plane on a submarine.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah. Yeah, he called it a– oh yeah, sort of–

IRA FLATOW: He said you could do that?

RANDALL MUNROE: –like a short, webbed runway.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah?

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah. He said you could, he said, but it can be hard to find a submarine when you need one.

IRA FLATOW: You also talked about how you’d have to land a plane if you couldn’t reach the controls.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, yeah. I tried a few–

IRA FLATOW: You throw things at them.

RANDALL MUNROE: I’ve looked– yeah, if you had your sleeve closed in the cockpit door, I figured, and you had to throw stuff at the controls. And he sounded like, that one, he didn’t think you’d have much chance of success in that scenario. But he talked about which controls you could conceivably hit and how he would try to do it.

I asked him, if he were locked on the outside of the plane somehow through some mishap, and crawling around on the surface as it was flying along, what part of the plane would he crawl to to try to take control somehow? And he had various answers.

And there was no delay. That was my favorite thing. I would ask the question and then he would just launch right into the answer as if it was like, oh sure, I’ve done this hundreds of times. This is a first-year pilot training kind of thing. And so that’s part of what made that just so much fun.

IRA FLATOW: That’s why he’s up there and we’re down here, because he can do that sort of stuff. We’re talking with Randall Munroe. We’re going to take a break. It’s a wonderful book. It’s called, how to in small caps. I don’t know why– everything is small caps– How To– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems.

If you’re looking for something to talk about tonight over a beer, this has some great stuff in it. We’re going to take a break, take your calls– 844-724-8255. Maybe you have something absurd that you would like to do. I have my own question that’s not in the book I want to talk to Randall about. 844-724-8255. Stay with us. We’ll be right back after this break.

This is Science Friday. I’m Ira Flatow. We’re talking to Randall Munroe, creator of the webcomic xkcd.com. His new book is called How To– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. Lots of people would like to talk to you. Let’s go to Amy in Tucson. Hi Amy.

AMY: Hi. Thanks for taking my call. I am so excited to share this work. One of my sons just started attending a STEM school here in Tucson. And I want to make sure that Randall’s work is on the radar of some of his teachers.

But my question for him is that my kids have taken part in an activity called Odyssey of the Mind, and I’m just wondering if that– it’s a creativity competition and it’s an international gig. And I’m just wondering if that’s ever been on Randall’s radar– if he’s ever lent his work towards that organization, or if he ever participated in it as a judge or a contestant.

IRA FLATOW: Randall? Ever heard of it?

RANDALL MUNROE: No, I haven’t. It sounds really cool. For me, when I was in high school, I competed in the first robotics competition. But I know there are a whole bunch of really similar– a bunch of similar programs, a bunch of other creativity competitions, and they’re all really cool. I was always vaguely intimidated but also really excited about them.

IRA FLATOW: Let me see if you can get excited about my question. We’ve been on the air almost 30 years now, and a repeated question we get asked all the time as a topic of discussion is, is it possible to build a space elevator? In other words, you would have an orbiting satellite that was in stationary orbit. You drop down a line to the earth and you have a moving door– a room– that goes up and down like a space elevator. Have you ever thought of that one?

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, that’s one of those ideas that’s right on the edge of something that physics suggests might be possible– just on the edge of possible– to where– and it would be such a huge undertaking that it’s really hard to even seriously start considering it. But at the same time, if you could build it, it would make access to space really easy. I think fundamentally we’ve got– there’s a few breakthroughs in materials that we need.

So if you want to build one of these space elevators, the physics all works out except for the strength of the strand itself– the tether that you’d be climbing up to get to space. That tether– we don’t have any material that’s strong enough to hold itself up as the Earth is spinning around in the weight of Earth’s gravity. And so we just need to figure out a way to make some kind of stronger material. And if we can do that, then it might be possible.

But we could do tethers other places in the solar system. That’s an interesting thing. And in my book, one of the things I talked about was the idea of dangling a tether from one of Mars’s moons. And this is an idea that I’m pretty sure is a bad idea– certainly impractical.

But I was surprised when I was sitting down to do calculations, how it seemed not quite as impractical as I thought– which was, if you dangle a tether from one of Mars’s moons, you could have the end of the tether drag in the atmosphere and then put wind turbines on that.

And they’d have to be supersonic wind turbines. But the tip of the tether would be going pretty fast, and you could generate a fair amount of power that way. You’d also cause the moon’s orbit to decay, so eventually it would crash into Mars and cause devastation.

IRA FLATOW: Details, details.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, you know. It’s like a lot of our energy sources– it would give us free power for now, and then have consequences later on. But we don’t need to worry about those. That’s the future.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah, it’s somebody else’s problem

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, exactly.

IRA FLATOW: Another question you looked into was powering a house on Mars.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, yeah. So I was trying to think of the different ways to get power on Mars. And so that’s what led me to the tether. I’d heard about space elevators on Mars as a way to get equipment off of the surface– to get rockets– because rocket launchers are so messy and expensive.

And so my idea was that you’d take– so they’re going to use these tethers to make it easier to get to space more cheaply. You can move supplies up and down, quickly build space stations. But I was thinking about, well, what if I had a house on Mars and I needed to produce power for it?

So I was thinking of all the usual tricks, like solar energy, geothermal energy, wind energy. And most of them don’t work as well on Mars or don’t work at all. Mars doesn’t have plate tectonics. The geothermal energy isn’t easy to get. It doesn’t have uranium deposits, because those require certain geologic processes to accumulate.

And so I was thinking of other weird ways to get power. And I had read about these tethers. And then I started thinking, hey, wait a minute. Mars’s air is really thin, but if you get something going really fast, like the end of this tether, maybe you could generate power that way. I still think it would be better– just mail batteries from Earth. But it’s a kind of cool idea.

IRA FLATOW: Yeah. Let’s go to the phones. Let’s go to Ryan in Jacksonville, Florida. Hi Ryan.

RYAN: Hey, how are you?

IRA FLATOW: Hey there. Go ahead.

RYAN: Yeah. I’m a TV producer– a golf producer– and we create videos every year for this series called Is it Drivable? And we set out to find if certain things are drivable. And this year, in May, we set out to see if Niagara Falls was drivable with a golf ball– hitting it from the Canadian side to the US side. John Daly tried it way back in 2005 and failed, because there’s a lot of elements with hitting a golf ball through the mist and the wind, and a lot of variables.

And this year we successfully did it. We got the world’s longest driver, Maurice Allen. And he hit it over on the fourth attempt. So it was quite fun to orchestrate that project.

IRA FLATOW: Is that from the Canadian side over to the American side by the American Falls? Or the Horseshoe?

RYAN: Correct. Yeah, so we had to close down the US side landing area, and we had to build a platform on the other side.

IRA FLATOW: Wow.

RYAN: One day we started and the weather was too bad. He couldn’t even attempt, and the mist was just so thick.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great.

RYAN: It was a lot of fun. And, so yeah, we enjoyed that.

IRA FLATOW: OK, thanks for calling.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah. Well, one of my favorite things about doing How To was I would be sitting there trying to come up with an idea, and I would think, that’s too ridiculous to work. And then I would go out and research it and discover that someone had actually tried it.

So I had a chapter on how to cross a river. And of course there’s the obvious. You could take a boat if there’s a boat. You could take a bridge if there’s a bridge. And I started thinking, OK, what if you don’t have those things? What are some other ways you could cross?

And one of the ideas I came up with was using a kite. You fly a kite up into the air, and then if you have a big enough kite, you can climb the string. And so you just get across the other side, and then maybe– I don’t know– cut some holes in the kite or something so that it starts fluttering down and land on the other side.

And I thought that was pretty ridiculous. But then I looked it up, and apparently when they were bridging Niagara Falls with a bridge back in the 1800s, they had– the canyon was too wide to shoot an arrow across the normal way, because it’s really quite wide. So normally they would shoot an arrow over towing a cable, and then have that pull a longer cable. And then that’s how they’d get the first pieces of rope across, and they’d use those to construct the bridge.

And so what they did instead was they ended up holding a kite-flying competition, where they had kids on either side try to fly kites and crash them on the other side. And then they could use the kite string to get the bridge started. And after a few days of trying, a kid I think named Homan Walsh ended up winning that competition by crossing the river. He didn’t cross himself, but with his kite string using this technique that I thought was useless.

I was just thinking of it as a fun exercise. But it actually worked. I’m always surprised when ideas I think are bad turn out to have an actual, practical application.

IRA FLATOW: I’m proud to say I’m one of the few people who have ever walked on Niagara Falls– when it was dried up in 19– the American Falls–

RANDALL MUNROE: Oh, that hasn’t done that yet.

IRA FLATOW: –in 1970.

RANDALL MUNROE: Oh, wow.

IRA FLATOW: And I was–

RANDALL MUNROE: That must have been cool to see.

IRA FLATOW: I was a reporter at WBFO and went out and looked over the edge on the drop off.

RANDALL MUNROE: Oh, that’s really cool. I’ve seen a couple of pictures from that. Yeah, there’s the urban legend that people think they turn the falls off at night, which they don’t. And no, they’ve been running continually since then. I’ve never had a chance to see that.

IRA FLATOW: They take a lot of the water out during the winter, because I’m following this– Mike Waters and I from NPR. We tried to throw a barrel over the American Falls, and there was so little water going over it, it just got stuck on the sides.

RANDALL MUNROE: Man, if you were trying to go over the falls in a barrel, that would be so stressful. You’re just sitting there bobbing, like, well, am I going to go over now? How about now?

IRA FLATOW: All right, we’ve got some phone calls. Let’s go to them. Let’s go to Tim in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Hi Tim.

TIM: Hi. So these are some thought experiments that I also thoroughly enjoy. Mine tend to be more for social problems. I figured out world peace. And then the one that actually has a technical aspect is how to stop school shootings– RFID chip interlocks on firearms– all new firearms. Eventually, the ones without them become only in the hands of collectors. And then schools have RFID blockers, so guns can’t fire.

IRA FLATOW: Randall, any thoughts on that?

RANDALL MUNROE: I mean, one thing I try to do in these situations is always look to research, and then see, have there been studies on this? This is an area where I don’t have a lot of studies. I don’t know. But that would be my criteria– has this been tried somewhere? Does it work?

And I feel like this about a lot of the solutions people suggest for this– is I don’t really know if it’s a good idea or not. And sometimes you can figure it out from theory, and sometimes you have to try it. And maybe things that seem like good ideas turn out to have problems you didn’t expect, or vice versa.

So I would say if these have been tried somewhere and we can see– does it have an effect or not? It turns it from a theoretical political argument to more of an empirical question. So I guess I’m always in favor of checking things with scientific research.

IRA FLATOW: I think something that you did do in the book– I’m trying to figure out because it looked so common– is you mentioned how you could charge your cell phone when you don’t have an outlet by putting a little generator in the water fountain, like a little–

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah.

IRA FLATOW: Like it generated– it’s water-powered. Did you actually do that?

RANDALL MUNROE: No. Well, so I figured Niagara Falls– and these big dams will generate power. And so could you do the same thing in your inside? Like if you’re in a mall or an airport, and you’ve got to charge your phone and can’t find an outlet. And this was another place where I thought it was kind of silly. But it would be fun to do the math and show why it’s silly, and then learn something about power.

And what I learned, again, was that it wasn’t quite as ridiculous as I thought. If you can really clamp on to a faucet of some kind and use the water pressure to drive a little turbine, you can generate a reasonable amount of power– not enough to run a big generator that would power a neighborhood, like a dam. But you could charge a phone.

And in fact, they actually did this. In the period when there was a lot of running water reaching people’s houses but they weren’t all electrified yet, the magazines had ads for these gadgets– these magneto hydro dynamos or something. They had some name. But it was a thing you attached to your faucet and use it to power the lights in your house. And I thought that was really funny. I had no idea someone had actually done that.

IRA FLATOW: That’s great. Somebody is always doing something. I’m Ira Flatow. This is Science Friday from WNYC Studios, talking with Randall Munroe, author of How To– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. Do we have some absurd people on the phones? Let’s try that. Let’s go to this line. Let’s go to Ellen in Nevada City, California. Hi Ellen from Nevada City.

ELLEN: Howdy, and I’m delighted to be talking with you. And I certainly hope, Randall, that you’re going to take these ideas to classrooms.

IRA FLATOW: Do you have a question for us?

ELLEN: It would be wonderful to have kids get enthusiastic about the way to solve problems. But I do have a question for you. And that is, how would you measure the terminal velocity of hailstones?

RANDALL MUNROE: Oh, man. So in physics, we love things like hailstones, because in physics, you always want to make everything as abstract and idealized as possible. And so that physicists like to assume that everything is a sphere and everything is frictionless, because it makes all the equations simpler. But hailstones are kind of these frictionless spheres. It’s very idealized.

So you can sit down with theory and figure out, using this drag equation, what the terminal velocity of a hailstone is. And because they’re such smooth, round objects, I think the match is pretty good. But if you want to check– because maybe it’s not– maybe there’s some other factor– I think the way they’ll often do that is they put them in what’s like a wind tunnel, but pointed upward.

And so you drop something in, and then you turn up the wind coming out of the ground going upward, and you see how fast it has to go before the hailstone lifts into the air and hovers. And then you can adjust the speed of the fan until the hailstone sits perfectly still, and then you measure how fast the air is flowing by. And that tells you its terminal velocity.

IRA FLATOW: It’s like that skydiving event they have, right? Where you sit in it– you’re in that wind tunnel.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, those look so much fun. Never tried one of those.

IRA FLATOW: [LAUGHS] Is there something you would like to try but you haven’t been able– or something that is beyond your grasp at the moment– that you can’t figure out an absurd scientific idea? In thinking– or is there nothing there? You know?

RANDALL MUNROE: Well, I did a chapter on– I did a chapter on how to take a selfie. And I find– and I think photography is really interesting.

IRA FLATOW: I read that.

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, yeah.

IRA FLATOW: You had something– you had to stretch your arm so far away that–

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, yeah. And I kind of use the term selfie loosely. I feel like people have started using it to mean any photograph of yourself, even if the camera is off on a tripod or something. And so I was kind of loose about it.

But I figured– what I was thinking was, it’s really fun to try to take a photo if you can get one of those cameras that can zoom in really far– where you’re standing in front of the sun or the moon. If you’re going to do to the sun, you got to use a lot of filters and stuff. But where you’ll see someone standing in front of the moon, and the moon looks really big behind them.

And the way you do that is by having someone stand on a hill really far away, and you have to wait till the moon is lined up with them. And that’s how they get those really dramatic photos of the moon setting behind, like the New York City skyline. To get those photos, it’s not that the moon is bigger that day or anything. You don’t need a supermoon. You just need to go out onto a mountain in New Jersey, and line everything up right.

IRA FLATOW: Randall, Randall. Have you ever heard of Photoshop? [LAUGHS]

RANDALL MUNROE: Yeah, yeah, that’s a lot easier. But come on, then you have the good story. You’re like, here’s this photo, and here’s what I had to do to get it.

IRA FLATOW: Here’s me getting arrested as I go to somebody’s property.

RANDALL MUNROE: I’ve always wanted to try doing one of those with Jupiter or Venus.

IRA FLATOW: OK.

RANDALL MUNROE: I think it’s possible, but I’ve never seen anyone do that.

IRA FLATOW: Report back when you can. Randall Munroe, author of How To– Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems. Great book. Nice to talk with you again.

RANDALL MUNROE: Oh, thank you so much. No, it was a lot of fun.

IRA FLATOW: And you can read an excerpt of his book on our website at sciencefriday.com/howto.

Copyright © 2019 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Alexa Lim was a senior producer for Science Friday. Her favorite stories involve space, sound, and strange animal discoveries.

Ira Flatow is the founder and host of Science Friday. His green thumb has revived many an office plant at death’s door.