A Blind Inventor’s Life Of Advocacy And Innovation

17:14 minutes

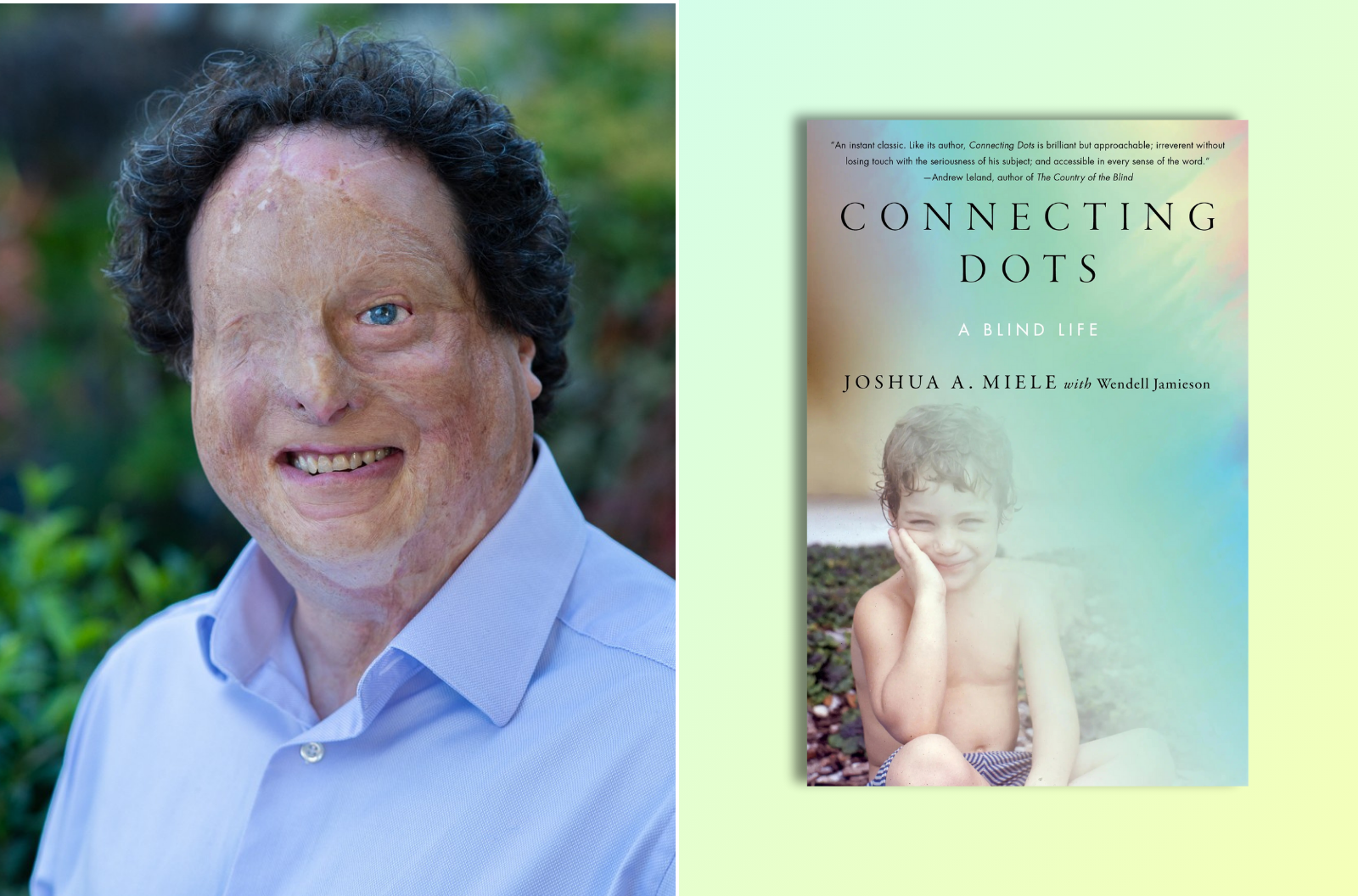

When inventor and scientist Josh Miele was 4 years old, a neighbor poured sulfuric acid on his head, burning and permanently blinding him. In his new book Connecting Dots: A Blind Life, Miele chronicles what happened afterwards, growing up as a blind kid, and how he built his career as an inventor and designer of adaptive technology.

Host Flora Lichtman talks with Dr. Joshua Miele, an Amazon Design Scholar and MacArthur Fellow, or “Genius Grant” recipient. They talk about the inspiration for the book, how he grew into his career, and how disabled people need to be included in the technology revolution.

Invest in quality science journalism by making a donation to Science Friday.

Joshua Miele, PhD, is a blind scientist, inventor, and Amazon Design Scholar. He’s based in Berkeley, California.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is Science Friday. I’m Flora Lichtman. When inventor and scientist Josh Miele was four years old, a neighbor poured sulfuric acid on his head, which burned and permanently blinded him. In his new book called Connecting Dots, A Blind Life, Josh chronicles what happened afterwards, growing up as a blind kid and how he built his career as an inventor and designer of adaptive technology.

Now, Dr. Joshua Miele is an Amazon design scholar and McArthur fellow AKA a Genius Grant recipient. Josh, welcome back to Science Friday.

JOSHUA MIELE: It’s so wonderful to be here. Thanks, Flora.

FLORA LICHTMAN: This is a personal book. You tell your story. Your family’s in it. Why did you want to write it?

JOSHUA MIELE: That’s a great question. My work is all about technology and accessibility and raising awareness of blindness and disability inclusion. And I think I just realized that writing a book would be a really powerful way of connecting with people who, number one, may not have any exposure to accessibility or disability. And number two, of course, I really want to be part of encouraging people who have disabilities to think more deeply about the technology that they use, the rights that we have, the way that we interact in the world and the opportunities that we all have and that technology either allows us to have or gets in the way of having.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Let’s talk about your family. You write that your mom and your family never left you out of anything because you couldn’t see. You all went to the movies, and your mom or your sister narrated. Your mom brought you to museums. Can you talk a little bit about this?

JOSHUA MIELE: When I was a child, nobody said to me, you can’t do this because you’re blind. Everybody always said, let’s figure out how you’re going to do this as a blind person.

My mom was actively and the culture around me, my family, my teachers was actively saying, you need to do things, like, encouraging me to do things, like, yes, I would go to museums, but my mom would take it the extra step and say, OK, the guard’s not looking now. Duck under this rope and feel this sculpture. The subversive nature of DIY accessibility, not only self-advocating, but taking the extra step to do what you have to do, whether it’s against the rules or not, to get the access you need in any given context.

And my mom was– not only was she willing to do it, she kind of sought out opportunities to break the rules in order to get me the access that I needed. And as a child, of course, I was horrified by it. I didn’t want to break the rules. But of course, it was hugely important in building the skill set and the attitudes that I have as an adult.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Such as?

JOSHUA MIELE: For example, one of the things that I created was an audio description platform called you describe that lets anybody in the world add audio description for accessibility for blind people to any YouTube video.

And while it doesn’t violate the terms of service of YouTube, there’s a real gray area there. Like, are we really allowed to annotate somebody else’s material. But my attitude about it was, I don’t actually care if it’s legal or not. I think people need this kind of access, and I would rather do it and get in trouble for it than live in a world where we just accept a lack of equal access to information for blind people.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah, similar to your mom.

JOSHUA MIELE: Just like my mom.

FLORA LICHTMAN: What about in school? I mean, as a sighted person, I think of science and math often as visual, like, equations diagrams, watching chemicals change color in a beaker. How did you adapt the course material into something that you could engage with?

JOSHUA MIELE: There are a number of ways in which I interacted with science. And I, of course, learned Braille at a very early age. Braille is a huge tool for blind people who need to be able to write equations or write or read in all sorts of ways.

And so I was super lucky to have a teacher who was able to transcribe all my stuff into Braille, my math, my science, my English. And all of the work that I would do in Braille, she would then take and with a pen just write, transcribe on the paper what I had written for my classroom teachers.

So it’s a lot of work, but that’s the kind of work that was at the time needed to really educate a blind kid in math and science. It’s really interesting that you would say that math and science are visual, because, of course, that’s the way most people do experience them.

But when you’re blind, my experience of math and science was not visual. Of course, it’s very spatial when you have a chart or a graph or an equation with a ratio or something like that. But if you represent them by touch, they’re still spatial the information is still there, and you can still interpret it by touch. So it’s not about vision. It’s about space.

FLORA LICHTMAN: That distinction between visual and spatial is so helpful. Thank you.

JOSHUA MIELE: Of course. And when you don’t have all of this visual input, our brains are capable of doing so much non-visual processing, in part, because we’re not– the brain is no longer being inundated with all this visual information. But we don’t– most of us don’t bother with it because vision is so useful.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So you grew up in New York, and you had your heart set on Berkeley because it had a good physics Department. You got in, and you quickly learned about the cave. Tell us about the cave.

JOSHUA MIELE: When I grew up in New York, of course, I was blind, but I didn’t embrace blindness. I didn’t know any blind adults. I didn’t really have any blind friends. And I didn’t really want to.

I didn’t want to think of myself as blind. I wanted to think of myself as someone who just happened to be blind. And when I went to Berkeley, that really got turned on its head. Because for the first time in my life, I met a community of amazing, smart, funny, clever, interesting, sweet, blind people who were also students at Berkeley and who were adults in the community.

Berkeley is one of the hotspots of disability rights and disability culture. And I didn’t know that at all when I came to Berkeley as an undergraduate. I just knew that they had a great physics department. And so I was, sort of, suddenly plunged into this very disability positive culture at Berkeley and was stunned by it.

And it was just amazing. And I realized at that time in the cave where, which was a, sort of, cultural center and educational resource for us, but it was also a place where we all went and would wind up talking and hanging out and–

FLORA LICHTMAN: Doing shots.

JOSHUA MIELE: –doing shots and all kinds of other unsavory undergraduate activities. And it was unbelievably enlightening.

And I just at that– ever since then, I don’t say I just happened to be blind. I say I am a blind scientist. I am a blind parent. I am a blind musician. And it’s because everything that I do in the world is impacted and influenced by my blind experience. And I’m not trying to minimize it. I’m proud of it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I love that. You recount stories in the book about walking around Berkeley and becoming more and more aware of how useless some of these accessibility modifications are. I would like you to talk to us about ATMs and why they suck.

JOSHUA MIELE: Well, they, certainly, used to suck. In the book, one of the things, one of the stories that I tell is in the late 90s, there were no accessible ATMs, but they did have Braille all over them because they didn’t want to put in the effort to make the ATMs talk.

I mean, they were computers. They could have talked. But quite frankly, it was a PR move because when sighted people see Braille all over the ATM, they think that it’s accessible. But of course it’s not, because what the Braille says is, if you need help getting money, go into the bank and ask for help, which is not an accessible device. It’s a cop out.

The ATMs are now accessible. If you have a plug-in earphone, you can insert it into the jack and put the other end into your ear, and the ATM will talk to you. And you can get your cash out of it just in time, I’ll say, for cash to be vanishingly irrelevant.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Just in time for it to be useless again in a different way.

JOSHUA MIELE: And now that none of us are carrying earphones anymore because we all use Bluetooth. But it took a lot of work by disability rights activists. And like all the other things in the world, things don’t stand still, right.

You do the work, you get the benefits, and then the world has moved on to the next thing. And you need to do the work over again. And we can hope that each iteration of new technology and new buildings and new streets is going to be better than the last one.

FLORA LICHTMAN: One of the stories you recount in the book is the story of you carrying vise grips around for street signs. Can you just tell us about that?

JOSHUA MIELE: I am all about information accessibility, and one of the most pervasive pieces of information that we live with in the world is signage and signs and street signs. When a sighted person looks around in the world, they see signs everywhere. And a blind person does not have any access to those.

So again, in the late 90s, before GPS, before we had technology that could help blind people know exactly where they were, I launched a one person campaign. I realized that street signs were actually embossed and that if you could climb up the pole to feel the street sign, you could know what intersection you were at.

And this was– like, the 8 foot pole. Yeah, like 8, 9 feet. And of course, climbing up a pole is difficult. And so what I came up with was the idea of carrying around, basically, a clamp that I could clamp onto the pole at about shoulder height. And I would heave myself up and stand on the clamp. And I could then hold on to the pole with one hand and read the sign with the other hand.

And it, of course, was kind of performance art because I would only do it when I absolutely had to. But people would see me doing it and say, excuse me, what are you doing. And it would give me this opportunity to say, well, I’m trying to find out what street this is. And accessibility is not just about inventing the technologies. It’s about creating the opportunities for the conversation about how things can be better.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I think that’s the perfect segue into some of your mapping inventions. Tell me about them.

JOSHUA MIELE: Maps are another great example of information that everyone who can see has ready access but which blind people are limited, very limited. And I wanted maps that could help me get from place to place.

Because one of the things that happens, I talked about the street signs, blind people who don’t have access to information about where they are or how the streets are laid out used to have to spend a lot of time getting lost, physically exploring on foot, finding their way from one place to another. And I just felt like that’s another example of how we are taxed on our time as people with disabilities.

We have to spend more time doing normal things than other people do. So my dream was to build a system that would let blind people have access to tactile street maps of any place they wanted. A tactile means touch, of course. So I created this thing called TMAP, the Tactile Maps Automated Production system that would take the information about the streets and produce it as a tactile map that could be felt.

And it’s really important to note that you can’t just take a visual map and make it into something that you can feel because you need to keep the graphics really simple in order to make them readable. So for the first time, blind people had the ability to look at neighborhoods and intersections and parks and campuses to help them plan, to help us plan routes from one place to another or just build a mental map of a place that you wanted to learn more about.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Yeah, to understand the spatial relationships.

JOSHUA MIELE: Exactly, exactly, without spending five hours wandering around that region getting lost.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Doing it by– literally by on foot.

JOSHUA MIELE: On foot.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Can we play with one of these?

JOSHUA MIELE: Yeah. So one of the things that I developed was a set of station maps for the BART system. BART is the San Francisco Bay area’s subway. They are maps of the stations themselves. So that when you go into a BART Station, it gives you access to knowing where you need to go in the train station to get in and out without getting bluntly lost in the station.

So one of the things we did with these BART maps was to use a computer operated smart pen that when you tap the pen on the map gives you labeling information about what the thing is that you’re tapping on. So if I tap on the top of the map, it’ll tell me what it is.

SPEAKER: BART Station, concourse level North.

JOSHUA MIELE: So it told me the name of the map. It told me the name of the station. It tells me that it’s looking at– I’m looking at the concourse level, not the street level or the platform level.

FLORA LICHTMAN: So you feel it with your finger, and then you use the pen to have it tell you more.

JOSHUA MIELE: Yeah, and you can use this system for all kinds of other things. But using it for maps lets people have access to spatial information about where they want to go and more independence, not only more independence but more confidence as they travel from one place to another.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Do any of these big advances in tech like AI, these large language models, robots, are they helpful for making the world more accessible? Are they making the world more accessible?

JOSHUA MIELE: Technology is always just a tool, but they are only as good as the way the tools are designed. And AI, while it has amazing uses for accessibility, can also be a barrier. For example, some people thought that they could just use AI to fix inaccessible websites, and in doing so, many of them made websites even less accessible than they would have been without the AI. One of the slogans of the disability rights movement is nothing about us without us, and that applies double or triple or quadruple in the development of technology for accessibility and disability.

FLORA LICHTMAN: I have to tell you, after I read your book, I started to really see the world differently. I just became much more aware of the bumps on the sidewalk or the Braille on the elevator buttons. And I wasn’t just noticing that they exist but wondering whether it was useful.

And so I just want to thank you for that. Thanks for making me more curious about the world. I appreciate it.

JOSHUA MIELE: I want to thank you for noticing it, and I want to thank you for taking from this book, I think, what I had tried to put into it.

FLORA LICHTMAN: Dr. Joshua Miele is an inventor and adaptive technology designer and the author of Connecting Dots, A Blind Life.

Copyright © 2025 Science Friday Initiative. All rights reserved. Science Friday transcripts are produced on a tight deadline by 3Play Media. Fidelity to the original aired/published audio or video file might vary, and text might be updated or amended in the future. For the authoritative record of Science Friday’s programming, please visit the original aired/published recording. For terms of use and more information, visit our policies pages at http://www.sciencefriday.com/about/policies/

Rasha Aridi is a producer for Science Friday and the inaugural Outrider/Burroughs Wellcome Fund Fellow. She loves stories about weird critters, science adventures, and the intersection of science and history.

Flora Lichtman is a host of Science Friday. In a previous life, she lived on a research ship where apertivi were served on the top deck, hoisted there via pulley by the ship’s chef.